Chapter 2. Using original documents on the Mexican American War

What are these texts?

These texts are digitized versions of

documents found in Rice University’s Woodson Research Center. They

are part of several hundred documents that comprise Rice’s Americas

Archive. The small selection of texts used in this Connexions

module all relate to the Mexican American War. I refer to a couple of the documents throughout the module but you may wish to browse through all six of the documents listed in the upper left corner. They would all be of use to someone writing a research paper on the Mexican American War.

The documents discussed in this module include a letter, a piece of currency, a message from U.S President Polk, and government documents regarding the Independence of Texas, the annexation of Texas, and the slave trade.

Why use these texts?

Many of the texts found in this archive were

purchased by Rice University from private collections. They have

not been used in scholarly studies before. In looking at the

documents – either on-line here or by going to Fondren Library’s

Woodson Research Center and viewing them in person - you are

tapping into new materials in the field of Hemispheric Studies. By

including information you find in them in research papers, you are

contributing new ideas to the field.

What am I looking at when I click on the links to these documents?

The links on the left sidebar take you to a page that describes the document in detail. For example, the page for the Independence of Texas document says that it was written by the US Congress House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1837. There are several key terms that are associated with the document and a paragraph that gives some historical background on its creation. There's also a link to this research module, a link to a module that contains more in-depth background information, and a link to the Americas Digital Archive home page. From the Americas Digital Archive home page, you can access many other documents and learn more about the collection.

At the bottom of the page, there are two links to the document. I recommend accessing the document via the top button that says "Full text with images." (The other option is not very reader-friendly.) This button takes you to a page with an easy-to-read transcription of the Independence of Texas and small images of the corresponding pages of the actual document. If you click on the small images, a new screen will open with a large image of the document page.

Is there an advantage to looking at the actual document instead of the digitized version?

If you can, I'd recommend using both the digitized and the actual document. It's exciting to get to see and hold important historical documents. You can feel the quality of the paper on which they were written, examine how they were bound, and look at their comparative sizes. The documents themselves are truly historical artifacts.

The digitized versions of the documents are clearly advantageous to people unable to visit the paper documents in Rice University's library. They are also much easier to work with over extended periods of time. (It's also easier on the documents if you do most of your work from the digitized versions.)

If I'm working from the digital archive, should I look at the transcription or images of the

actual document?

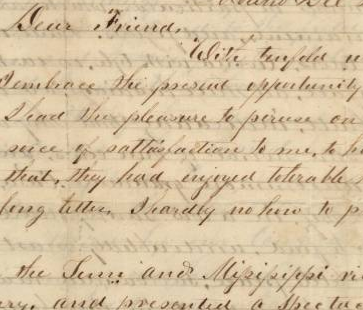

Both the transcription and the original

version have something to offer. The transcriptions are often

easier to read. You can probably skim through a transcription a lot

faster than a handwritten letter from 150 years ago to determine if

the document will be of interest to you. In preparing a paper for a

class, you may not have time to peruse all the texts that might be

loosely related to your topic in their original format, but you

could probably skim through a lot of their transcriptions and

narrow your selection.

If you find that a particular text will be

useful in your research, looking at the original document is of

great value. Sometimes a handwritten letter can tell you about its

author: if s/he was in a hurry, if s/he possessed the handwriting

of a well-educated (and hence usually wealthy) person, if s/he

experienced trouble in writing sections of the document with

crossed out words, among other things. For example, the letter written by Mattock contains many spelling errors, which have been noted in the transcription. But the steady handwriting would not suggest that the writer wrote in haste; perhaps he simply did not know how to spell well.

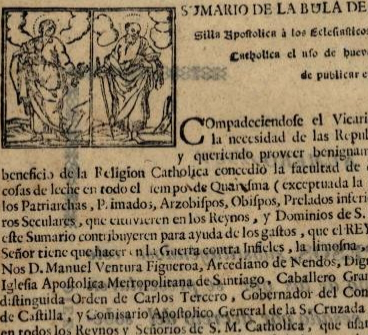

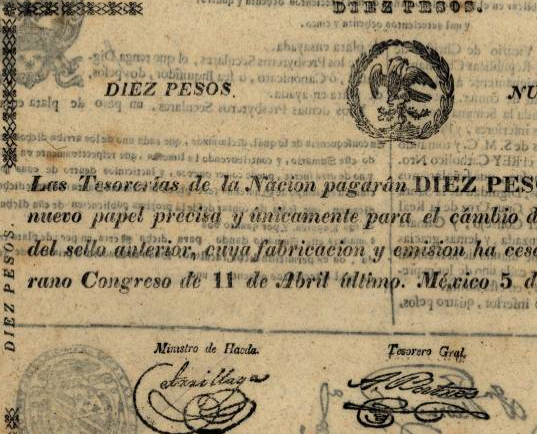

Even a typed document that is more official

in nature than a handwritten letter is worthwhile looking at in its

original format. For example, take a look at the Texas currency

document. You can easily see that the front and back are in fact

two different documents by the different typefaces and formats

used. In the transcription, this difference is not visually

noticeable. Yet the difference between the two texts is great: one

side is a papal bull printed in 1784 and the other states that the paper has an

exchange value. The currency was printed in 1823 on the back of the out-dated papal bull because of a severe paper shortage in Mexico.

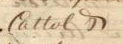

Another advantage to looking at the original

text in a digitized format is that transcriptions are

interpretations. If you work from a transcription, you must cite

the transcription – not the original document – as your source. A

transcription might have typos or (as is more likely with today’s

spell checking features) might correct errors in the original. In addition, the transcriber

might not have devoted as much time to his/her interpretation of

the original as you would like to and might have left some words

marked as illegible. You may wish to put in a little more research

to decipher what such words are if the document is of particular

importance. For example, in the Mattock letter again, there is a word the transcriber interpreted as "(attol)". However, it might make sense as "Cattol," a mispelling of "cattle." You might have still other ideas about what the writer meant.

If you notice any errors or “corrected” errors or decipher any words marked as illegible, please let us know!

For more information on the relative value of

transcriptions and original documents in research projects, please

refer to the module "Using Untranslated Materials in Research."