supportive family life; the familiar, settled com-

Artists and intellectuals were paid to create

munity; the natural and eternal rhythms of nature

murals and state handbooks. These remedies

that guide the planting and harvesting on a farm;

helped, but only the industrial build-up of World

the sustaining sense of patriotism; moral values

War II renewed prosperity. After Japan attacked

inculcated by religious beliefs and observations

the United States at Pearl Harbor on December

— all seemed undermined by World War I and its

7, 1941, disused shipyards and factories came to

aftermath.

bustling life mass-producing ships, airplanes,

Numerous novels, notably Hemingway’s The

jeeps, and supplies. War production and experi-

Sun Also Rises (1926) and Fitzgerald’s This Side mentation led to new technologies, including the

of Paradise (1920), evoke the extravagance and nuclear bomb. Witnessing the first experimental

disillusionment of the lost generation. In T.S.

nuclear blast, Robert Oppenheimer, leader of

Eliot’s influential long poem The Waste Land

an international team of nuclear scientists,

(1922), Western civilization is symbolized by a

prophetically quoted a Hindu poem: “I am

bleak desert in desperate need of rain (spiritual

become Death, the shatterer of worlds.”

renewal).

The world depression of the 1930s affected

MODERNISM

most of the population of the United States.

he large cultural wave of Modernism,

Workers lost their jobs, and factories shut down;

which gradually emerged in Europe and the

T

businesses and banks failed; farmers, unable to

United States in the early years of the 20th

harvest, transport, or sell their crops, could not century, expressed a sense of modern life

pay their debts and lost their farms. Midwestern

through art as a sharp break from the past, as

droughts turned the “breadbasket” of America

well as from Western civilization’s classical tradi-into a dust bowl. Many farmers left the Midwest

tions. Modern life seemed radically different

for California in search of jobs, as vividly

from traditional life — more scientific, faster,

61

more technological, and more mechanized.

towers to illumine a forbidding outer darkness

Modernism embraced these changes.

suggesting ignorance and old-fashioned tradition.

In literature, Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) de-

Photography began to assume the status of a

veloped an analogue to modern art. A resident of

fine art allied with the latest scientific developParis and an art collector (she and her brother

ments. The photographer Alfred Stieglitz opened

Leo purchased works of the artists Paul Cézanne,

a salon in New York City, and by 1908 he was

Paul Gauguin, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Pablo Pi-

showing the latest European works, including

casso, and many others), Stein once explained

pieces by Picasso and other European friends of

that she and Picasso were doing the same thing,

Gertrude Stein. Stieglitz’s salon influenced nu-

he in art and she in writing. Using simple, con-

merous writers and artists, including William

crete words as counters, she developed an

Carlos Williams, who was one of the most influ-

abstract, experimental prose poetry. The child-

ential American poets of the 20th century.

like quality of Stein’s simple vocabulary recalls

Williams cultivated a photographic clarity of

the bright, primary colors of modern art, while

image; his aesthetic dictum was “no ideas but in

her repetitions echo the repeated shapes of

things.”

abstract visual compositions. By dislocating

ision and viewpoint became an essential

grammar and punctuation, she achieved new

aspect of the modernist novel as well. No

V

“abstract” meanings as in her influential collec-

longer was it sufficient to write a straight-

tion Tender Buttons (1914), which views objects forward third-person narrative or (worse yet)

from different angles, as in a cubist painting:

use a pointlessly intrusive narrator. The way the

story was told became as important as the story

A Table A Table means does it not my

itself.

dear it means a whole steadiness.

Henry James, William Faulkner, and many

Is it likely that a change. A table

other American writers experimented with fic-

means more than a glass

tional points of view (some are still doing so).

even a looking glass is tall.

James often restricted the information in the

novel to what a single character would have

Meaning, in Stein’s work, was often subordi-

known. Faulkner’s novel The Sound and The Fury nated to technique, just as subject was less

(1929) breaks up the narrative into four sections, important than shape in abstract visual art.

each giving the viewpoint of a different character Subject and technique became inseparable in

(including a mentally retarded boy).

both the visual and literary art of the period. The To analyze such modernist novels and poetry, a

idea of form as the equivalent of content, a cor-

school of “New Criticism” arose in the United

nerstone of post-World War II art and literature,

States, with a new critical vocabulary. New Critics crystallized in this period.

hunted the “epiphany” (moment in which a char-

Technological innovation in the world of facto-

acter suddenly sees the transcendent truth of a

ries and machines inspired new attentiveness to

situation, a term derived from a holy saint’s

technique in the arts. To take one example: Light, appearance to mortals); they “examined” and

particularly electrical light, fascinated modern

“clarified” a work, hoping to “shed light” upon it artists and writers. Posters and advertisements

through their “insights.”

of the period are full of images of floodlit

skyscrapers and light rays shooting out from

automobile headlights, moviehouses, and watch-

62

POETRY 1914-1945:

translations introduced new liter-

EXPERIMENTS IN FORM

ary possibilities from many cultures

Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

to modern writers. His life-work

Ezra Pound was one of the most

was The Cantos, which he wrote and

influential American poets of this

published until his death. They con-

century. From 1908 to 1920, he

tain brilliant passages, but their

resided in London where he asso-

allusions to works of literature and

ciated with many writers, including

art from many eras and cultures

William Butler Yeats, for whom he

make them difficult. Pound’s poetry

worked as a secretary, and T.S.

is best known for its clear, visual

Eliot, whose Waste Land he drasti-

images, fresh rhythms, and muscu-

cally edited and improved. He was a

lar, intelligent, unusual lines, such

link between the United States and

as, in Canto LXXXI, “The ant’s a cen-

Britain, acting as contributing edi-

taur in his dragon world,” or in

tor to Harriet Monroe’s important

poems inspired by Japanese haiku,

Chicago magazine Poetry and

such as “In a Station of the Metro”

spearheading the new school of

(1916):

poetry known as Imagism, which

advocated a clear, highly visual pre-

The apparition of these faces in

sentation. After Imagism, he cham-

the crowd;

pioned various poetic approaches.

Petals on a wet, black bough.

He eventually moved to Italy, where

he became caught up in Italian

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

Fascism.

Thomas Stearns Eliot was born in

ound furthered Imagism in

St. Louis, Missouri, to a well-to-

letters, essays, and an an-

do family with roots in the north-

Pthology. In a letter to Monroe

eastern United States. He received

T.S. ELIOT

in 1915, he argues for a modern-

the best education of any major

sounding, visual poetry that avoids

American writer of his generation

“clichés and set phrases.” In “A

at Harvard College, the Sorbonne,

Few Don’ts of an Imagiste” (1913),

and Merton College of Oxford Uni-

he defined “image” as something

versity. He studied Sanskrit and

that “presents an intellectual and

Oriental philosophy, which influ-

emotional complex in an instant of

enced his poetry. Like his friend

time.” Pound’s 1914 anthology of 10

Pound, he went to England early

poets, Des Imagistes, offered

and became a towering figure in the

examples of Imagist poetry by out-

literary world there. One of the

standing poets, including William

most respected poets of his day, his

Carlos Williams, H.D. (Hilda

modernist, seemingly illogical or ab-

Doolittle), and Amy Lowell.

stract iconoclastic poetry had re-

Pound’s interests and reading

volutionary impact. He also wrote

were universal. His adaptations and

influential essays and dramas, and

brilliant, if sometimes flawed, Photo courtesy Acme Photos championed the importance of lit-63

erary and social traditions for the

Let us go and make

modern poet.

our visit.

As a critic, Eliot is best remem-

bered for his formulation of the

Similar imagery pervades The

“objective correlative,” which he

Waste Land (1922), which echoes

described, in The Sacred Wood, as a

Dante’s Inferno to evoke London’s

means of expressing emotion

thronged streets around the time of

through “a set of objects, a situa-

World War I:

tion, a chain of events” that would

be the “formula” of that particular

Unreal City,

emotion. Poems such as “The Love

Under the brown fog of a winter

Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915)

dawn,

embody this approach, when the

A crowd flowed over London

ineffectual, elderly Prufrock thinks

Bridge, so many

to himself that he has “measured

I had not thought death had

out his life in coffee spoons,”

undone so many... (I, 60-63)

using coffee spoons to reflect a

humdrum existence and a wasted

The Waste Land’s vision is ulti-

lifetime.

mately apocalyptic and worldwide:

The famous beginning of Eliot’s

“Prufrock” invites the reader into

Cracks and reforms and bursts

tawdry alleys that, like modern life,

in the violet air

offer no answers to the questions

Falling towers

life poses:

Jerusalem, Athens, Alexandria

Vienna London

Let us go then, you and I,

Unreal (V, 373-377)

When the evening is spread

out against the sky

liot’s other major poems

Like a patient etherized upon

include “Gerontion” (1920),

E

a table;

which uses an elderly man

Let us go, through certain half-

to symbolize the decrepitude of

deserted streets,

Western society; “The Hollow Men”

The muttering retreats

(1925), a moving dirge for the death

Of restless nights in one-night

of the spirit of contemporary hu-

cheap hotels

manity; Ash-Wednesday (1930), in

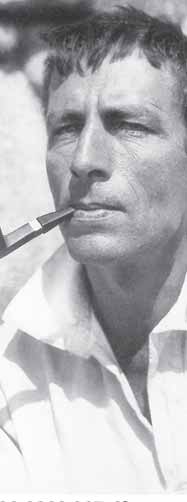

ROBERT FROST

And sawdust restaurants with

which he turns explicitly toward the

oyster-shells:

Church of England for meaning in

Streets that follow like a

human life; and Four Quartets

tedious argument

(1943), a complex, highly subjec-

Of insidious intent

tive, experimental meditation on

To lead you to an overwhelm-

transcendent subjects such as

ing question...

time, the nature of self, and spiritu-

Photo © Kosti Ruohamaa,

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Black Star

al awareness. His poetry, especially

64

his daring, innovative early work,

snow.

has influenced generations.

My little horse must think it

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

queer

Robert Lee Frost was born in

To stop without a farmhouse

California but raised on a farm in

near

the northeastern United States

Between the woods and frozen

until the age of 10. Like Eliot and

lake

Pound, he went to England, attract-

The darkest evening of the year.

ed by new movements in poetry

there. A charismatic public reader,

He gives his harness bells a

he was renowned for his tours. He

shake

read an original work at the inaugu-

To ask if there is some mistake.

ration of President John F. Kennedy

The only other sound’s the

in 1961 that helped spark a national

sweep

interest in poetry. His popularity is

Of easy wind and downy flake.

easy to explain: He wrote of tradi-

tional farm life, appealing to a nos-

The woods are lovely, dark and

talgia for the old ways. His subjects

deep,

are universal — apple picking,

But I have promises to keep,

stone walls, fences, country roads.

And miles to go before I sleep,

Frost’s approach was lucid and

And miles to go before I sleep.

accessible: He rarely employed pe-

dantic allusions or ellipses. His fre-

Wallace Stevens (1879-1955)

quent use of rhyme also appealed

Born in Pennsylvania, Wallace

to the general audience.

Stevens was educated at Harvard

Frost’s work is often deceptively

College and New York University

simple. Many poems suggest a

Law School. He practiced law in

deeper meaning. For example, a

New York City from 1904 to 1916,

quiet snowy evening by an almost

a time of great artistic and poetic

hypnotic rhyme scheme may sug-

activity there. On moving to Hart-

gest the not entirely unwelcome

ford, Connecticut, to become an

approach of death. From: “Stopping

insurance executive in 1916, he

by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

continued writing poetry. His life is

(1923):

remarkable for its compartmental-

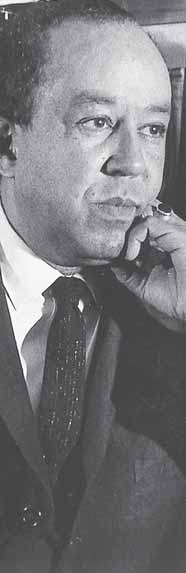

WALLACE STEVENS

ization: His associates in the insur-

Whose woods these are I think I

ance company did not know that he

know.

was a major poet. In private he con-

His house is in the village,

tinued to develop extremely com-

though;

plex ideas of aesthetic order

He will not see me stopping

throughout his life in aptly named

here

books such as Harmonium (en-

To watch his woods fill up with

Photo © The Bettmann Archive larged edition 1931), Ideas of Order 65

(1935), and Parts of a World (1942). Some of his or sailor — will always find a creative outlet.

best known poems are “Sunday Morning,” “Peter

Quince at the Clavier,” “The Emperor of Ice-

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)

Cream,” “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a

William Carlos Williams was a practicing pedi-

Blackbird,” and “The Idea of Order at Key West.”

atrician throughout his life; he delivered over

Stevens’s poetry dwells upon themes of the

2,000 babies and wrote poems on his prescrip-

imagination, the necessity for aesthetic form and

tion pads. Williams was a classmate of poets Ezra

the belief that the order of art corresponds with

Pound and Hilda Doolittle, and his early poetry

an order in nature. His vocabulary is rich and var-reveals the influence of Imagism. He later went

ious: He paints lush tropical scenes but also

on to champion the use of colloquial speech; his

manages dry, humorous, and ironic vignettes.

ear for the natural rhythms of American English

Some of his poems draw upon popular culture,

helped free American poetry from the iambic

while others poke fun at sophisticated society or

meter that had dominated English verse since

soar into an intellectual heaven. He is known for

the Renaissance. His sympathy for ordinary

his exuberant word play: “Soon, with a noise like

working people, children, and everyday events in

tambourines / Came her attendant Byzantines.”

modern urban settings make his poetry attractive

Stevens’s work is full of surprising insights.

and accessible. “The Red Wheelbarrow” (1923),

Sometimes he plays tricks on the reader, as in

like a Dutch still life, finds interest and beauty in

“Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock” (1931):

everyday objects:

The houses are haunted

So much depends

By white night-gowns.

upon

None are green,

Or purple with green rings,

a red wheel

Or green with yellow rings,

barrow

Or yellow with blue rings.

None of them are strange,

glazed with rain

With socks of lace

water

And beaded ceintures.

People are not going

beside the white

To dream of baboons and periwinkles.

chickens.

Only, here and there, an old sailor,

Drunk and asleep in his boots,

Williams cultivated a relaxed, natural poetry. In

Catches tigers

his hands, the poem was not to become a perfect

In red weather.

object of art as in Stevens, or the carefully re-

created Wordsworthian incident as in Frost.

his poem seems to complain about

Instead, the poem was to capture an instant of

unimaginative lives (plain white night-

time like an unposed snapshot — a concept he

Tgowns), but actually conjures up vivid derived from photographers and artists he met images in the reader’s mind. At the end a drunk-at galleries like Stieglitz’s in New York City. Like en sailor, oblivious to the proprieties, does

photographs, his poems often hint at hidden pos-

“catch tigers” — at least in his dream. The poem

sibilities or attractions, as in “The Young

shows that the human imagination — of reader

Housewife” (1917):

66

accounts, and historical facts. The

At ten a.m. the young housewife

layout’s ample white space sug-

moves about in negligee behind

gests the open road theme of

the wooden walls of her

American literature and gives a

huband’s house.

sense of new vistas even open to

I pass solitary in my car.

the poor people who picnic in the

public park on Sundays. Like

Then again she comes to the

Whitman’s persona in Leaves of

curb,

Grass, Dr. Paterson moves freely

to call the ice-man, fish-man,

among the working people:

and stands

shy, uncorseted, tucking in

-late spring,

stray ends of hair, and I

a Sunday afternoon!

compare her

To a fallen leaf.

- and goes by the footpath to the

cliff (counting: the proof)

The noiseless wheels of my car

rush with a crackling sound over

himself among others

dried leaves as I bow and pass

- treads there the same stones

smiling.

on which their feet slip as they

climb,

He termed his work “objectivist”

paced by their dogs!

to suggest the importance of con-

crete, visual objects. His work often

laughing, calling to each other -

captured the spontaneous, emotive

pattern of experience, and influ-

Wait for me!

enced the “Beat” writing of the

(II, i, 14-23)

early 1950s.

Like Eliot and Pound, Williams

BETWEEN THE WARS

tried his hand at the epic form, but

Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962)

while their epics employ literary

umerous American poets of

allusions directed to a small num-

stature and genuine vision

N

ber of highly educated readers,

ROBINSON JEFFERS

arose in the years between

Williams instead writes for a more

the world wars, among them poets

general audience. Though he stud-

from the West Coast, women, and

ied abroad, he elected to live in the

African-Americans. Like the nov-

United States. His epic, Paterson

elist John Steinbeck, Robinson

(five vols., 1946-1958), celebrates

Jeffers lived in California and wrote

his hometown of Paterson, New

of the Spanish rancheros and In-

Jersey, as seen by an autobiograph-

dians and their mixed traditions,

ical “Dr. Paterson.” In it, Williams

and of the haunting beauty of the

juxtaposed lyric passages, prose,

land. Trained in the classics and

Photo © UPI/The Bettmann

letters, autobiography, newspaper

Archive

well-read in Freud, he re-created

67

themes of Greek tragedy set in the

whistles far and wee

rugged coastal seascape. He is best

known for his tragic narratives such

and eddieandbill com