By determining their periods of

use, we can narrow down the period in which the Souvenir of Egypt might have been

produced and thus make a more informed argument about the silk's significance. Some

of these flags you may recognize right away, and some may be completely foreign to

you. Even a familiar flag, however, could be subtly different from the one you are

identifying with it. Consider how the flag of the United States has changed over

time.

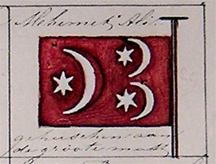

Note the key features of this flag: it includes three crescent and star pairs in white

on a red background. In our search for the identity of this flag we will be drawing heavily

on the resources available at Rice's Fondren Library. However, the same techniques are applicable at most

libraries.

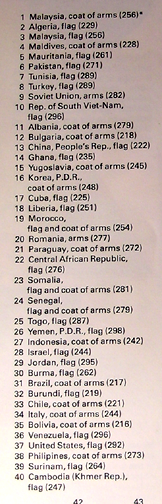

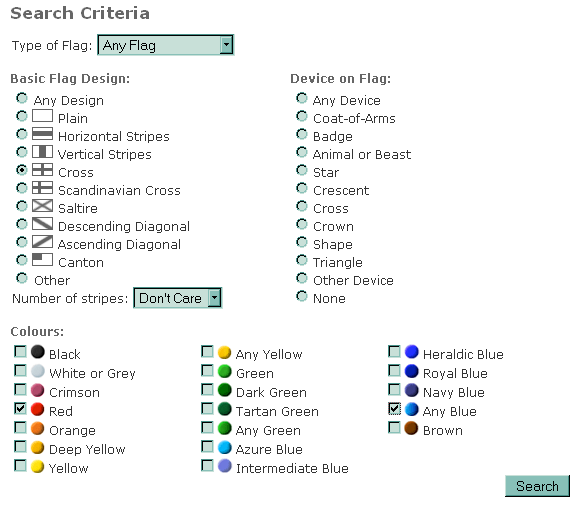

Let's begin with the online catalog to see what sort of

resources are available there for us to use. Visit WebCat, enter "flags of the world," select the keyword

bubble above the box, and then select the Search Everything option. If you would

like a review of using online catalogs please visit our library catalog module.

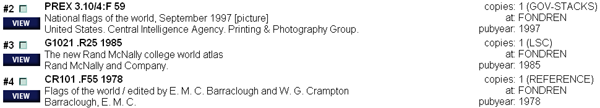

Results two, three, and four look promising.

Result six reminds us that flags change over time, often into

completely different designs than the previous flag.

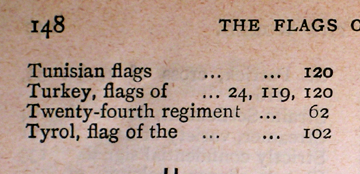

Results eleven and twelve also seem to address the history of flags and the way

they change over time. An earlier publication

might contain information that newer books would leave out in favor of more

recent developments.

Getting an exact match for our flag will require a bit of browsing.

Let's gather up several of these resources so that we can review their contents

for the information we need in one sitting. Besides, you will notice the similarities in their call

numbers.

Remember that similar books are grouped together for their content. When

you visit the stacks, you should always look around for other related material.

We have settled on three works to begin with--those of W.J.

Gordon, F. Edward Hume, and Whitney Smith. Let's work from oldest to most

recent. It is important for research involving such time-dependent

artifacts as flags that we pay close attention to exactly when the information

we are gathering on each flag was published.

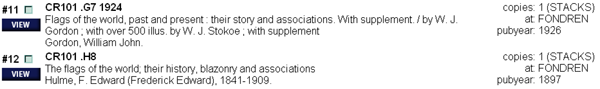

"The Flags of the World; Their History, Blazonry and Associations" written

by F. Edward Hulme in 1897

In 1897 the world was a very different place. Consider

for a moment the position of Britain. In 1897 the British Empire stretched over the entire globe and claimed a

hold over the lands of hundreds of thousands of people who, today, recognize

themselves as citizens of independent nations. This is an aspect of Hulme's perspective that we may

want to consider when reading his work.

A brief author search in the catalog reveals that Hulme wrote

quite a few books in his time and on a variety of subjects. Although we do not

know if he was an expert on the subject we are researching, we do know that he

felt qualified to write on wildflowers, symbolism in religious art, the meanings

of proverbs, interpretations of natural formations in European architecture,

and floral design for the home and garden, and, as the listing on the title page of Flags of

the World says,

&c., &c.".

What does this tell us? We know that the author felt qualified to write

about a variety of things, not an uncommon self-attribution in Hulme's day, but

yielding a less expert analysis than, say, someone who has spent his or her life

studying one subject.

On the first page of the introduction, Hulme offers his

perspective on the nature and function of heraldry:“"So soon as man passes from the

lowest stage of barbarism the necessity for some special sign, distinguishing man from man,

tribe from tribe, nation from nation, makes itself felt; and this prime necessity once met,

around the symbol chosen spirit-stirring memories quickly gather that endear it, and make it

the emblem of the power and dignity of those by whom it is borne... the distinctive Union Flag

of Britain, the tricolor of France, the gold and scarlet bars of the flag of Spain, all alike

appeal with irresistible force to the patriotism of those beneath their folds, and speak to

them of the glories and greatness of the historic past, the duties of the present, and the

hopes of the future..."”

We have here several imperial motifs, such as the path from barbarism to

civilization, the association of patriotism with emblems, etc. Although these observations do

not immediately relate to our current task of identifying the flags, they could suggest a

direction for a project examining, for instance, the social and political function of flags.

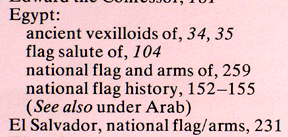

We do not locate our flag specifically in Hulme's book, but we do find this:

Notice the two flags on the bottom of the page. We have a paired crescent moon

and a star on a red background, but not three crescent/star pairs.

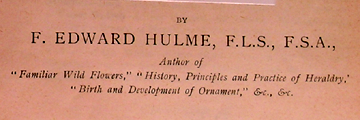

We check the appendix for our plate number (listed atop the

images), 21

and find the region of origin, Turkey. If we then look to the index at the

back of the book...

we find Turkey's location in the text. Let's see what Hulme has to say

about the flags:

“"The crescent moon and star... were adopted by the Turks as their device on the capture of

Constantinople by Mahomet II, in 1453. They were originally the symbol of Diana, the Patroness

of Byzantium, and were adopted by the Ottomans as a badge of triumph. Prior to that event,

the crescent was a very common charge in the armorial bearings of English Knights, but it fell

into considerable disuse when it became the special device of the Mohamedans, though even so

late as the year 1464 we find Rene, Duke of Anjou, founding an Order of Knighthood

having as its badge the crescent moon, encircled by a motto signifying 'praise by increasing.'”

This historical information may prove relevant, particularly

the association of the star and crescent with Constantinople

since 1453. Let's move on the next work.

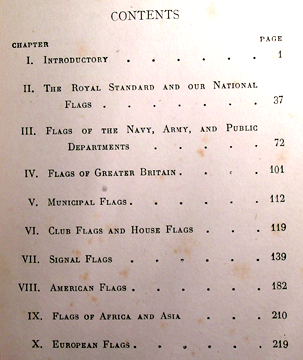

"Flags of the World, Past and Present : Their Story and Associations"

written by William John Gordon in 1926

Published thirty years after Hulme's book, Gordon's work likely includes

all that has changed after World War I. This is important for our research in

particular because of the marked impact that WWI had on the borders and national

identities of the Arab World. Let's jump to the table of contents and see about our

options.

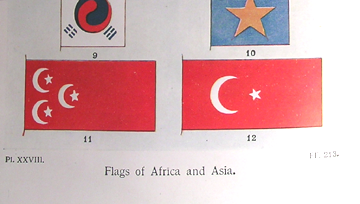

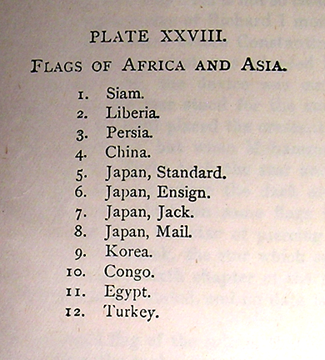

Flags of Africa and Asia seems to be the most promising section for our

purposes, considering what we have learned so far about our flag.

Note that flags 11 and 12 closely resemble our flag. Let's see where the appendix lists

these flags as originating from.

We discover that flag 11 is Egypt's, while 12 is Turkey's. Let's see

what Gordon has to say about Egypt, looking it up in the

index.

“Gordon writes: "The crescent is more a symbol of Constantinople than of the Turks, and

it dates from the days of Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. When, so the

legend runs, that enterprising monarch besieged Byzantium in 339 B.C he met with repulse after

repulse and tried as a last resource to undermine the walls, but the crescent moon shone out so

gloriously that the attempt was discovered and the city saved. And thereupon the Byzantines

adopted the crescent as their badge, and Diana, whose emblem it was, as their patronness.

When the Roman emperors came, the crescent was not displaced, and it continued to be the city

badge under the Christian emperors. In 1453, when Mohammed the Second took Constantinople, it

was still to the fore, and being in want of something to vary the monotony of the plain red

flag under which he had led his men to victory, he, with great discrimination, availed

himself of the old Byzantine badge, explaining that it meant Constantinople on a field of

blood..." ”

“"Where the star came from is not so clear. A star within a

crescent was a badge of Richard I more than two hundred and fifty years before Constantinople

fell, which implies that the crescent was adopted by the Saracens if, as we are told, the

device was emblematic of the crusades and the star stood for the star of Bethlehem. In his badge

Richard placed the crescent on its back and the star above it; but when Mohammedanism became

triumphant the Turks took the star and placed it with the upright crescent where the dark area

of the moon should be, from which on some flags it has emerged. Others tell us it is the star

of piercing brightness, the morning star, Al Târek, the star which appeareth by the night of

the eighty-sixth chapter of the Korân..."

”

More embellishment on the story we read in Hulme. But what of the

history of our flag? Let's try the third book.

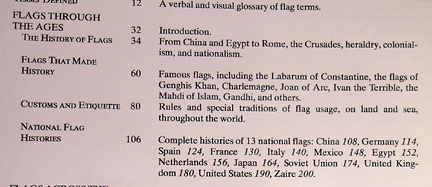

“Flags Through the Ages and Across the World” written by Whitney Smith in

1975

Smith's book promises to provide useful historical perspective.

By 1975 the world had witnessed national conflict of all kinds,

including a second world war and countless localized skirmishes dividing

existing nations and producing new ones. A brief Author search in the catalog

tells us that Smith has written many books, every one about flags.

Let's take a look at the table of contents for our options.

Just what we are looking for, National Flags and their Histories. But

Smith's book has much more to offer than that, as we shall see. Looking in the

index we find an interesting option: Star(s) and moon, symbolism of, 316-317. If we skip to p. 316, we find a collection of such flags,

as well as a numbered index for their origins.

However, when we scan the page for our flag we find an unpleasant piece

of evidence...

It is not often that the one page in a book that you need is the one that has been

torn out.

But such frustrations serve as a reminder of the care required of us

when we are permitted to use such resources. With a stiff lip and the

resolve of the determined historian, we move on.

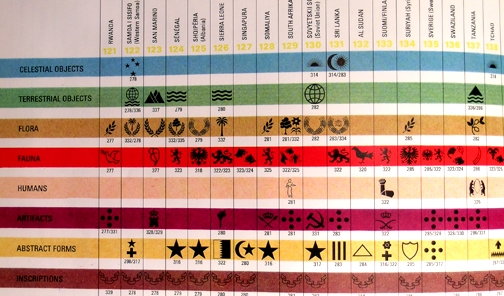

As we continue to browse this book we find our symbol in this

fascinating chart.

It seems that Smith has categorized the flags in the work by symbol and

form as well, the footprint of a specialist indeed.

A scan of the index brings us to the pages on Egypt, the nation

of origin for our flag.

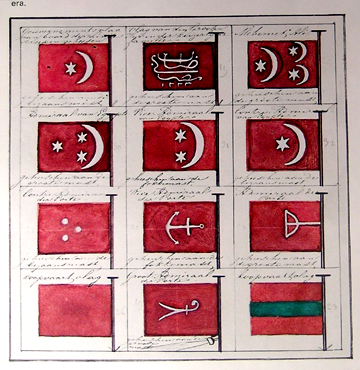

We have a number of options; let's go right to the history page.

The first thing we see is our flag along side many other similar flags,

an indication of its evolution over the years.

A closer look reveals the handwritten words "Mehmet Ali." The

adjoined paragraph explains:

“The Ottoman flag in the nineteenth century normally bore a white star and crescent on

its red field, although both Turkish and Egyptian ships very frequently displayed the old,

plain red ensign. Muhammad Ali did introduce one distinctive new flag which eventually became

the first real Egyptian national flag. Perhaps to symbolize the victory of his armies in three

continents (Europe, Asia, and Africa) or his own sovereignty over Egypt, Nubia, and the Sudan,

Ali set three white crescents and three stars on a red field. Technically only the personal

standard of Muhammad Ali--and of those who followed him as hereditary rules of Egypt under the

title of khedive--the flag was at least a mark of distinction between Egypt and Turkey.”

But it is the next page that fully satisfies our immediate

needs.

This chart identifies the period and location of this flag's use. Based on this

evidence, we can determine that our flag served as the flag of Egypt and Sudan from 1914-1923.

We have gained a good

amount of information and gathered a few valuable resources. Let's move on to

the next flag.