Chapter 6

Pretty soon the old man was up and around again, and then he went for Judge Thatcher in the courts to make him give up the money, and he went for me too, for not stopping school. He caught me a few times and whipped me, but I went to school just the same, and was able to hide from him or run away most of the time. I didn’t want to go to school much before, but I I wanted to go now to get back at pap. That court business was so slow -- seemed they weren’t ever going to get started on it; so every now and then I’d ask for two or three dollars off of the judge for pap, to keep from getting a whipping. Every time he got money he got drunk; and every time he got drunk he made trouble around town; and every time he made trouble he got locked up. He was just perfect for that -- this kind of thing was right up his line.

He got to hanging around the widow’s too much and so she told him at last that if he didn’t quit coming around there she would make trouble for him. Well, wasn’t he angry? He said he would show who was Huck Finn’s boss. So he watched out for me one day at the end of winter, and caught me, and took me up the river about three mile in a flat bottom boat, and crossed over to the Illinois side where there was lots of trees and no houses but a rough old log cabin in a place where the trees was so thick you couldn’t find it if you didn’t know where it was.

He kept me with him all the time, and I never got an opening to run off. We lived in that old cabin, and he always locked the door and put the key under his head nights. He had a rifle which he had robbed, I’d say, and we fished and hunted, and that was what we lived on. Every little while he locked me in and went down to the shop, three miles, to where he gave fish and other animals for whiskey, and would bring it home and get drunk and have a good time, and whip me.

The widow she found out where I was by and by, and she sent a man over to get hold of me; but pap forced him off with the rifle, and it weren’t long after that before I was used to being where I was, and liked it -- all but the whipping part.

It was kind of lazy and fun, resting all day, smoking and fishing, and no books or study. Two months or more run along, and my clothes got to be all holes and dirt, and I didn’t see how I’d ever got to like it so well at the widow’s, where you had to wash, and eat on a dish, and smooth your hair, and go to bed and get up at special times, and be forever worrying over a book, and have old Miss Watson talking at you all the time.

I didn’t want to go back no more. I had stopped using bad words, because the widow didn’t like it; but now I took to it again because pap hadn’t no problem with it. It was pretty good times up in the trees there, take it all around.

But by and by pap got too enthusiastic with his whipping stick, and I couldn’t stand it. I was all over sores. He got to going away so much, too, and locking me in. Once he locked me in and was gone three days. It was awful being there all alone. I judged he had got drowned, and I wasn’t ever going to get out any more. I was scared. I made up my mind I would fix up some way to leave there. I had tried to get out of that cabin many a time, but I couldn’t find no way. There weren’t a window to it big enough for a dog to get through. I couldn’t get up the chimney; it was too narrow. The door was thick, solid flat pieces of timber. Pap was pretty careful not to leave a knife or anything in the cabin when he was away; I would say I had hunted the place over as much as a hundred times; well, I was most all the time at it, because it was about the only way to put in the time. But this time I found something at last; I found an old dirty saw blade without any handle; it was in between a horizontal board and the angle boards of the roof. I oiled it up and went to work. There was an old horse-blanket nailed against the logs at the far end of the cabin behind the table, to keep the wind from blowing through the holes and putting the candle out. I got under the table and lifted the blanket, and went to work to saw a piece of the bottom log out -- big enough to let me through. Well, it was a good long job, but I was getting toward the end of it when I heard pap’s rifle in the distance. I cleaned up any signs of my work, and dropped the blanket and put my saw back, and pretty soon pap come in.

Pap wasn’t in a good spirit -- like he is most of the time. He said he had been down in town, and everything was going wrong. His lawyer said he believed he would win his argument and get the money if they ever got started; but then there was ways to put it off a long time, and Judge Thatcher knowed how to do it. And he said people were saying there’d be another move to get me away from him and give me to the widow for my care, and they believed it would win this time. This shook me up a lot, because I didn’t want to go back to the widow’s any more and be so squeezed up and straight. Then the old man got to using bad words, and he used them against everything and everybody he could think of, and then did them all over again to make sure he hadn’t missed any, and after that he finished off with a kind of a general shout all around, with quite a lot of people which he didn’t know the names of, and so he called them what’s-his-name when he got to them, and went right along with his bad words.

He said he would like to see the widow try and get me. He said he would watch out, and if they tried any such game on him he knowed of a place six or seven mile off to hide me in, where they might hunt until they dropped and they couldn’t find me. That made me pretty scared again, but only for a minute; I made my mind up that I wouldn’t stay on hand long enough for him to do that.

The old man made me go to the boat and bring the things he had got. There was a fifty-pound bag of corn meal, and a side of salted pig meat, bullets, and a four-gallon container of whiskey, and a few other things. I carried up some of it, and went back and sat down on the front of the boat to rest. I thought it all over, and I thought I would walk off with the rifle and some lines, and take to the trees when I run away. I wouldn’t stay in one place, but just walk right across the country, mostly night times, and hunt and fish to keep alive, and get so far away that the old man or the widow couldn’t ever find me any more. I planned to saw my way out and leave that night if pap got drunk enough, and I believed he would. I got so full of thinking about it I didn’t know how long I had been staying at the boat until the old man shouted and asked me if I was asleep or drowned.

I got the things all up to the cabin, and then it was about dark. While I was cooking dinner the old man took a drink or two and got himself warmed up, and went to angry talking again. He had been drunk over in town, sleeping all night in the open, and he was something to look at. A body would a thought he was Adam -- he was just all mud.

Whenever his whiskey started to work he most always went for the government. This time he says: "Call this a government? Why, just look at it and see what it’s like. Here’s the law a-standing ready to take a man’s son away from him -- a man’s own son, which he has had all the trouble and all the worry and all the cost of caring for. Yes, just as that man has got that son growed up at last, and ready to go to work and start to do something for him and give him a rest, the law up and goes for him. And they call that government! That ain’t all, either. The law backs that old Judge Thatcher up and helps him to keep me out of my money. Here’s what the law does: The law takes a man worth six thousand dollars and more, and squeezes him into an old prison of a cabin like this, and lets him go round in clothes that ain’t good enough for a pig. They call that government? A man can’t get his rights in a government like this. Sometimes I’ve a strong feeling to just leave the country for good and all. Yes, and I told ‘em so; I told old Thatcher so to his face. Lots of 'em heard me, and can tell what I said. Says I, for two cents I’d leave this awful country and never come near it again. Them’s the very words. I says look at my hat -- if you can call it a hat -- but the top sticks up and the rest of it goes down until it’s below my face, and then it ain’t really a hat at all, but more like my head was pushed up through a piece of stove pipe. Look at it, says I -- such a hat for me to wear -- and me one of the richest men in this town if I could get my rights.

"Oh, yes, this is a wonderful government, wonderful. Why, look here. There was a free nigger there from Ohio -- half and half he was, almost as white as a white man. He had the whitest shirt on you ever seen, too, and the cleanest hat; and there ain’t a man in that town that’s got as good clothes as what he had; and he had a gold watch and chain, and a silver-headed walking stick -- the awfulest old grey-headed businessman in the country. And what do you think? They said he was a teacher in a university, and could talk all kinds of languages, and knowed everything. And that ain’t the worst. They said he could vote when he was at home. Well, that let me out. Thinks I, what is the country a-coming to? It was voting day, and I was just about to go and vote myself if I wasn’t too drunk to get there; but when they told me there was a place in this country where they’d let that nigger vote, I pulled out. I says I’ll never vote again. Them’s the very words I said; they all heard me; and the country may come to nothing for all I care -- I’ll never vote again as long as I live. And to see the cool way of that nigger -- why, he wouldn’t a give me the road if I hadn’t pushed him out of the way. I says to the people, why ain’t this nigger put up for sale and sold? -- that’s what I want to know. And what do you think they said? Why, they said he couldn’t be sold until he’d been here for six months, and he hadn’t been there that long yet. There, now - - that’s proof. They call that a government that can’t sell a free nigger until he’s been one place six months. Here’s a government that calls itself a government, and lets on to be a government, and thinks it is a government, and yet it’s got to sit doing nothing for six whole months before it can take a hold of a travelling, robbing, awful, white-shirted free nigger, and -- "

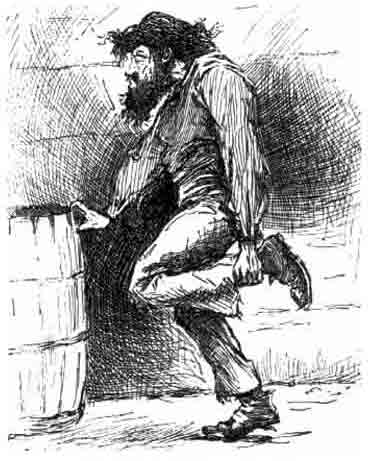

Pap was a-going on so he never saw where his old legs was taking him to, so he went head over heels over the bucket of salted pig meat and took skin off the front of both legs. After that his talking was all the hottest kind of language -- mostly hitting at black people and the government, but he give the bucket some, too, all along, here and there. He jumped around the cabin a lot, first on one leg and then on the other, holding first on one leg and then onto the other, and at last he let out with his left foot and give the bucket a shaking kick.

But it weren’t a good choice, because that was the shoe that had two or three of his toes hanging out the front end of it; so now he let out a shout that was enough to make a body’s hair stand up, and down he went in the dirt, and lay there, holding his toes; and the bad words he used then stood over anything he had ever done before. He said so himself after that. He had heard old Sowberry Hagan in his best days, and he said it stood over him, too; but I think that was kind of putting it on, maybe.

After dinner pap took the bottle, and said he had enough whiskey there for two drunks and one round of the dreaming shakes. I judged he would be blind drunk in about an hour, and then I would take the key, or saw myself out, one or t’other. He went on drinking and drinking, and fell down on his blankets by and by; but luck didn’t run my way. He didn’t go deep asleep, but was moving around. He groaned and moaned and threw his arms and legs around this way and that for a long time. At last I got so tired it was all I could do to keep my eyes open, and so before I knowed what I was about I was deep asleep, and the candle was still burning.

I don’t know how long I was asleep, but all out of the quiet there was an awful shout and I was up. There was pap looking wild, and jumping around every which way and shouting about snakes. He said they was coming up his legs; and then he would give a jump and shout, and say one was biting him on the cheek -- but I couldn’t see no snakes. He started to run around and around the cabin, shouting "Take him off! take him off! he’s biting me on the neck!" I never seen a man look so wild in the eyes. Pretty soon he was all tired out, and fell down breathing real fast; then he turned over and over wonderful fast, kicking things every which way, and hitting and reaching at the air with his hands, and crying and saying there was devils took a-hold of him. He tired out by and by, and was quiet a while, moaning. Then he was quieter still, and didn’t make a sound. I could hear the owls and the wolves away off in the trees, and it seemed awful quiet. He was laying over by the corner of the cabin.

By and by he lifted himself up part way and listened, with his head to one side.

He says, very low: "Step -- step -- step; that’s the dead; step -- step -- step; they’re coming after me; but I won’t go. Oh, they’re here! Don’t touch me -- don’t! Hands off -- they’re cold; let go. Oh, let a poor devil alone!"

Then he went down on all fours and moved around like that, begging them to let him alone, and he covered himself up in his blanket and squeezed in under the old table, still a-begging; and then he went to crying. I could hear him through the blanket.

By and by he come out and jumped up on his feet looking wild, and he seen me and went for me. He ran after me around and around the place with a pocket-knife, calling me the Angel of Death, and saying he would kill me, and then I couldn’t come for him no more. I begged, and told him I was only Huck; but he laughed such an awful laugh, and shouted and used bad words, and kept on coming after me. Once when I turned short and raced under his arm he made a reach and got me by the coat between my shoulders, and I thought I was gone; but I come out of that coat fast as lightning, and saved myself. Pretty soon he was all tired out, and dropped down with his back against the door, and said he would rest a minute and then kill me. He put his knife under him, and said he would sleep and get strong, and then he would see who was who.

I climbed up as soft as I could, not to make any noise, and got down the rifle. I pushed the stick down it to make sure it had gunpowder in it, then I rested it on the top of a barrel, pointing toward pap, and sat down behind it to wait for him to move. And how slow and quiet the time did go by.