Chapter 17

In about a minute someone spoke out of a window without putting his head out, and says:

"Be done, boys! Who’s there?"

I says: "It’s me."

"Who’s me?"

"George Jackson, sir."

"What do you want?"

"I don’t want nothing, sir. I only want to go along by, but the dogs won’t let me."

"What are you looking around here for this time of night?"

"I weren’t looking around, sir, I fell off the river boat."

"Oh, you did, did you? Bring a light here, someone. What did you say your name was?"

"George Jackson, sir. I’m only a boy."

"Look here, if you’re telling the truth you needn’t be afraid -- nobody’ll hurt you. But don’t try to move; stand right where you are. Wake up Bob and Tom, some of you, and bring the guns. George Jackson, is there anyone with you?"

"No, sir, nobody."

I heard the people moving around in the house now, and I seen a light. The man shouted out: "Take that light away, Betsy, you stupid old thing -- don’t you understand? Put it on the floor behind the front door. Bob, if you and Tom are ready, take your places."

"All ready."

"Now, George Jackson, do you know the Shepherdsons?"

"No, sir; I never heard of them."

"Well, that may be, and it may not. Now, all ready. Step forward, George Jackson. And remember, don’t hurry -- come very slowly. If there’s anyone with you, let him stay back -- if he shows himself we’ll shoot. Come along now. Come slow; push the door open yourself -- just enough to squeeze in, you hear?"

I didn’t hurry; I couldn’t if I’d a wanted to. I took one slow step at a time and there weren’t a sound, only I thought I could hear my heart. The dogs were as quiet as the people, but they followed a little behind me. When I got to the three log steps in front of the door I heard them taking off locks and bars. I put my hand on the door and pushed it a little and a little more until someone said, "There, that’s enough -- put your head in." I done it, but I judged they would take it off.

The candle was on the floor, and there they all was, looking at me, and me at them, for about fifteen seconds: Three big men with guns pointed at me, which made me pull back in fear, I tell you; the oldest, grey and about sixty, the other two thirty or more -- all of them strong and good looking -- and the sweetest old grey-headed woman, and back of her two young women which I couldn’t see right well.

The old man says: "There; I think it’s all right. Come in."

As soon as I was in the old man he locked the door and put a bar across it, and told the young men to come in with their guns, and they all went in a big room that had a new cloth rug on the floor, and got together in a corner that was out of the line of the front windows. They held the candle, and took a good look at me, and all said, "Why, he ain’t a Shepherdson -- no, there ain’t any Shepherdson about him."

Then the old man said he hoped I would agree to him feeling me for weapons, because he didn’t mean nothing by it -- it was only to make sure. So he didn’t put his hands into my pockets, but only felt outside with his hands, and said it was all right. He told me to make myself easy and at home, and tell all about myself; but the old woman says: "Why, bless you, Saul, the poor thing’s as wet as can be; and don’t you think it may be he’s hungry?"

"Right you are, Rachel -- Forgive me for not thinking of it."

So the old woman says: "Betsy" (This was a black woman.) "you fly around and get him something to eat as fast as you can, poor thing; and one of you girls go and wake up Buck and tell him -- oh, here he is himself. Buck, take this little stranger and get the wet clothes off him and dress him up in some of yours that’s dry."

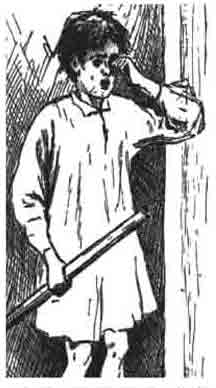

Buck looked about as old as me -- thirteen or fourteen or along there, but he was a little bigger than me. He hadn’t on anything but a shirt, and his hair was very messy. He came in with his mouth wide open and digging one fist into his eyes, and he was pulling a rifle along with the other hand.

He says: "Ain’t they no Shepherdsons around?"

They said, no, it was a false warning.

"Well," he says, "if they’d been some, I think I’d a got one."

They all laughed, and Bob says: "Why, Buck, they might have killed us all, you’ve been so slow in coming."

"Well, nobody come after me, and it ain’t right I’m always put down; I don’t get no show."

"Don’t worry, Buck, my boy," says the old man, "you’ll have show enough, all in good time, don’t you worry about that. Go along with you now, and do as your mother told you."

When we got up to his room he got me a rough shirt and a short coat and pants of his, and I put them on.

While I was at it he asked me what my name was, and then he started to tell me about a blue-bird and a young rabbit he had caught in the trees day before yesterday, and he asked me where Moses was when the candle went out. I said I didn’t know; I hadn’t heard about it before, no way.

"Well, try," he says.

"How am I going to try," says I, "when I never heard tell of it before?"

"But you can try, can’t you? It’s just as easy."

"Which candle?" I says.

"Any candle," he says.

"I don’t know where he was. Where was he?"

"He was in the dark! That’s where he was!"

"Well, if you knowed where he was, what'd you ask me for?"

"Why, shoot, it’s a joke, don’t you see? Say, how long are you going to stay here? You got to stay always. We can just have great times -- they don’t have no school now. Do you own a dog? I’ve got a dog -- and he’ll go in the river and bring out sticks that you throw in. Do you like to brush up Sundays, and all that kind of foolishness? You can be sure I don’t, but mum she makes me. I hate these old pants! I’d better put ‘em on, but I’d be happier not, it’s so warm. Are you all ready? All right. Come along, old horse."

Cold corn-bread, cold salt-meat, butter and milk -- that is what they had for me down there, and there ain’t nothing better that ever I’ve come across yet. Buck and his mum and all of them smoked corn pipes, all but the black woman, who was gone, and the two young women. They all smoked and talked, and I eat and talked. The young women had quilts around them, and their hair down their backs. They all asked me questions, and I told them how pap and me and all the family was living on a little farm down at the bottom of Arkansas, and my sister Mary Ann run off and got married and never was heard of no more, and Bill went to hunt them and he weren’t heard of no more, and Tom and Mort died, and then there weren’t nobody but just me and pap left, and he was just cut down to nothing, because of his troubles; so when he died I took what there was left, because the farm didn’t belong to us, and started up the river, sleeping out on the floor of the ship, and fell over into the river; and that was how I come to be here. So they said I could have a home there as long as I wanted it. With Jim gone and all, I could see this was as good a plan as any I could think of.

Then it was almost morning and everybody went to bed, and I went to bed with Buck, and when I waked up in the morning, end it all, I couldn’t remember what my name was. So I was lying there about an hour trying to think, and when Buck waked up I says:

"Can you spell, Buck?"

"Yes," he says.

"I don’t think you can spell my name," says I.

"What you don’t think I can? I can," says he.

"All right," says I, "go ahead."

"G-e-o-r-g-e J-a-x-o-n -- there now," he says.

"Well," says I, "you done it, but I didn’t think you could. It ain’t no easy name to spell -- right off without studying."

I wrote it down secretly, because someone might want me to spell it next, and so I wanted to be good with it and spell it easy, like I did it all the time.

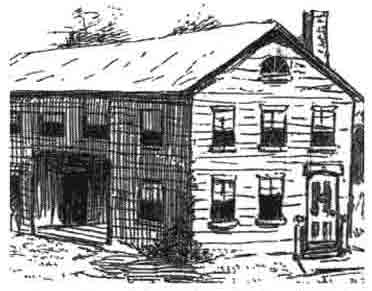

It was a mighty nice family, and a mighty nice house. I hadn’t seen no house out in the country before that was so nice.

They had pictures hanging on the walls -- mostly soldiers and wars. But there was some that one of the daughters, Emmeline, which was dead now, had made herself when she was only fifteen years old. Everybody was sorry she died, because she had planned out a lot more of these pictures to do, and a body could see by what she had done what they had lost. They kept Emmeline’s room clean and nice, and all her things in it just the way she liked to have them when she was alive, and nobody ever used the room to sleep in. The old woman took care of it herself, when it was easy to see there was enough slaves to do it, and she sewed there a lot and read her Bible there. All in all I was thinking that I had landed in the nicest family I could think of.