Principals in large districts may spend a whole career never developing more than a superficial knowledge of district financial and operation management. This is not likely to occur in small

districts. In very small districts, principals are typically required to be lead managers for selected district-wide management functions.

Initial training for current superintendents to perform and supervise district level management activities ideally begins during the initial assistant principal level and continues to principal and central office experience. Most new superintendents today possess central office experience prior to the superintendency. There should be a seamless path of professional development in

management training, abilities, and experiences. Today, educational administration training and preparation is conceptually disjointed between building and central office levels.

In the last decade, a majority of new superintendents have come from the ranks of central office administrators than in past decades (Glass, Bjork, & Brunner, 2000; Glass, 2002). This change in traditional career path offers opportunities for future superintendents to begin articulated training for district executive management while serving in both building and central office administrative roles.

Current Paths of Preparation

Along with current discrepancies in superintendent preparation, certification requirements vary from state to state. In the past certification requirements have “driven” content of superintendent preparation. Certification or licensing codes generally require university coursework and passing a written exam. In about 30 states, the certification or licensure code is closely or loosely based on 6

standards developed for a “generic” K-12 principal position (Council of Chief State School

Officers, 1996).

This application of generic “principal standards” may be due to the traditional structure of many university superintendent programs being extensions of principal preparation (Kowalski & Glass, 2000). Standards developed by the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium and the

National Policy Board for Education Administration. Standards documents essentially are

guidelines pointing out “general” areas of concern to the profession.

Administrators typically “space” their university preparation program out over many years. A

good example of “time” displacement is that an initial school law class taken in the principal

preparation will be followed by an advanced class in the educational specialist or doctoral

program. This is often not the case (Kowalski & Glass, 2000). This part-time effort toward

administrator preparation results in a situation where the university programs are populated by part-time students in very drawn out part-time and poorly sequenced programs.

The national number of superintendents yearly “needing” new certificates is about 2,200, as the superintendent turnover rate has hovered around 14 % for several decades. Superintendent tenure currently is between 6 to 7 years (Glass, 2003b). Critics argue there are hundreds to thousands of

“unused” superintendent certificates. This is true but superintendent applicant pools are more and more “local” each year. Applicants apply frequently only for nearby positions. About 60 % of

superintendents have a professionally employed “trailing spouse” (Glass, Bjork, & Brunner,

2000).

Most states grant superintendent certification in toto for districts of all sizes and types. Some states require superintendents participate minimally in “Administrator Academy” programs but

for the most part “actual” superintendent preparation is through on the job training supplemented by university content laden coursework. Entry into the field is through self-selection from a career path beginning with classroom teaching (about 5 years). Superintendents from non-teaching

backgrounds presently hold a very small number of superintendencies (Glass, 2002b).

Higher Education Preparation

Traditionally, superintendents have gained access to credentials and positions through attendance in university based (heavily management based) degree and credential programs. In past decades

most states have required about 30 semester hours of coursework beyond the masters degree for a superintendent’s credential. In numerous educational administration programs this 30 to 36

semester hours culminates in an educational specialist’s degree. Or, it satisfies a significant portion of the coursework required for a doctoral degree.

University coursework, theoretically training superintendents to be “management experts” beyond the principal’s office, requires courses in school finance, personnel administration, school law, and very occasionally facility planning. In recent years many, if not most, educational

administration programs have eliminated “management” types of courses in favor of policy and

leadership since superintendents should be “leaders” not mere managers. The result has been the majority of “management” training has been through on the job experiences and spasmodic or

periodic in-service training provided by districts or state agencies (many times by private

vendors).

How Superintendents Might Be Trained for Management Roles

There are few if any supporters of current superintendent preparation programs. A reason being

there are so few stand alone programs. Most preparation programs consolidate the superintendent credential into doctoral course program requirements. Strangely, to criticize superintendent

credentialing is to criticize doctoral programs! This has created a situation where superintendent preparation has been “pushed” out of the way for academics.

This paper will not debate the appropriateness or inappropriateness of existing quasi-programs or the few stand-alone providing services to a small handful of aspiring superintendents. They serve a miniscule number of the year 2000 new superintendents (Glass, 2002). Superintendents

themselves have over the years evaluated their preparation programs to be “good.” Interestingly, this positive evaluation is also held by “superintendent leaders” in the profession (Glass, 2002).

A key question is what agencies or institutions might best provide superintendent training to

manage tax payer supported school districts. Historically, this has been largely the role of

graduate programs in educational administration, housed in institutions of higher education. A

modicum of pre and post employment training has been provided by professional associations,

state agencies, and the occasional district. Perhaps the primary expectation held by the profession has been for higher education programs to provide important content knowledge. The skill

training necessary for actual day to day work is left to chance or loosely organized.

Preparation program content for principals and superintendents has been and is still dominated by certification and licensing requirements. What is required for licensing and certification is what is taught. An example is that until the 1980’s most states required a school facility planning class.

Today, only one or two states require the class and most educational administration programs no longer require or teach it. This is despite the need to replace aging infrastructure in a majority of the nation’s school districts.

One possible course of action to guarantee superintendent managerial expertise may be to

restructure present certification requirements. Considering the critical nature of management, a separate or extended certification might be provided by a specialized university preparation track that is supplemented by direct state agency involvement. University programs should not continue to be isolated from local districts and the state agency in licensing superintendents.

This restructured certificate or license should be sized for large, medium, and small districts. It seems incongruent to certify a superintendent-manager for responsibility to manage a budget

ranging from one million to one billion dollars. Present superintendent certification assumes a superintendent is qualified for any size of district. This assumption may have been appropriate 50

years ago but not in today’s complex world of public education.

Role of Professional Associations

In developing or creating a new or restructured certificate, states might choose to require

superintendents to obtain professional recognitionfrom a national or state professional

association. A good example of a professional recognition program is one currently sponsored by the Association of School Business Officials. Applicants wishing to become recognized school

business officials must meet criteria based on academic preparation, specialized training,

experience, and recommendations from other practicing Registered School Business Officials.

This program fills a void in school business officer state certification and university based

preparation.

A possible model for superintendent executive management recognition is a coordinated

consortium effort by universities, state agencies, and professional organizations. The university role would be to academically prepare applicants in appropriate content knowledge and essential skills enriched by field based experiences (practicum) aligned to course content/standards. The state agency’s role would insure essential skills and knowledge were assessed and validated. The state agency might additionally assume responsibility to provide training in “essential” skills beyond university preparation requirement levels. The university and state, then together, could recommend candidates to professional associations for a “recognition” (or registration)

assessment at the appropriate district size and budget level.

Portfolio review and interviews by professional organizations certainly seem to be logistically feasible. Each year about 2,200 new superintendents (about 50% new to the superintendency)

actually are employed from pools averaging from10 to 20 applicants (Glass, 2002). At the state

level, the normal annual turnover of superintendents is about 20 %. National associations could organize and complete the recognition process working in conjunction with state affiliates.

The AASA currently provides numerous professional development opportunities for its

membership. State affiliates often offer an even greater and broader number of opportunities.

Although AASA might be thought to be the “lead” organization in preparing superintendents,

other groups such as the principal associations provide professional development closely aligned with some aspects of the superintendency.

Numerous professional organizations serve superintendents and central office administrators;

superintendents (AASA), personal directors (American Society for Public Administration

[ASPA]), business managers (Association of School Business Officials [ASBO]), facility directors (Council of Educational Facility Planners International [CEFPI]), and curriculum directors

(Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development [ASCD]) along with umbrella

organizations such as the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA) ,

National Council of Professors of Educational Administration (NCPEA), University Council on

Educational Administration (UCEA), National Council of Professors of Educational

Administration and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The American

Association of Management (AAM) might also be considered an allied professional group. These

organizations sponsor numerous training opportunities for members. Several have made recent

efforts to become quasi-licensing organizations.

Recognition Levels

The vast range of district sizes, types, and budgets create a three tier “mastery” of professional superintendent management: (1) executive management, (2) registered management, and (3)

qualified management. This scheme would accommodate district size differences as executive

superintendent managers would likely be found in very large districts, registered managers in

medium sized districts, and qualified managers in smaller districts.

A separate setof requirements need to be developed for each tier. An applicant should not

necessarily be required to begin at the bottom tier. Many experienced central office administrators may be well prepared for the “executive management” tier without first going through the

“registered” and “qualified” tiers.

A reasonable question evolving from this scheme is whether principals and central office

administrators might be discouraged from seeking the superintendency because of raised levels

for preparation, assessment, licensing, and professional recognition. A recent study found there to be no lack of qualified applicants for superintendents (Glass & Bjork, 2003).

Superintendent applicants with demonstrated and “recognized” management expertise in all

likelihood would be more desirable (and qualified) candidates for vacant superintendent positions.

Professional recognition by universities, states, and professional organizations would accentuate the importance of competent district management. Many boards now seem to “assume” that every

state licensed superintendent is a competent manager of district fiscal, human, and physical

resources. Considering the haphazard manner of current preparation and licensing, this simply is not true in a high percentage of cases. Superintendent research shows management expertise is

and has been, over the years, the prime hiring criteria used by boards (Glass, Bjork & Brunner, 2000).

The Role of Standard and Performance Indicators

Many essential skills and knowledge bases are currently being offered by higher education

programs as required by state sponsored programs and standards based licensing requirements.

Specific management skills areas such as cash accounting, auditing, and financial investing are often provided by private sector groups.

Current National Policy Board and Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium ( ISLLC)

standards are vague and insufficient to serve as an accurate means to identify and verify quality district superintendent management. In fact, the ISLLC “performance indicators” do not even

mention essential areas of district management! And, they do not differentiate between district sizes, budgets, types, and programs (Council of Chief State School Officers, 1996). The

performance indicators, while mostly appropriate, are merely outline “statements” of required

training and performance.

The AASA superintendent standards are sufficiently credible (validated) to serve as an appropriate initial launch point for establishing a “management curriculum” for the superintendency (Hoyle, 1993). A credible training program should be based on both validated standards and indicators.

This joint undertaking between higher education preparation programs, state agencies, and

professional associations to develop a “validated” training program could prove to district

improvement.

The depth of a “management” curriculum is precise and detailed. An example would be that

superintendents must be able to insure the state accounting manual provisions are being adhered to in a proper manner. Few superintendents have taken undergraduate courses in accounting and

fewer have had a general introduction to accounting in their education administration preparation program. These state accounting manuals are typically hundreds of pages of complex information

and detailed forms. This information is currently only provided occasionally by state agencies and professional associations and rarely provided by higher education classes. Most often this

information is acquired (sometimes well and sometimes not so well) via on the job training. Many citizens might be quite upset to learn their superintendent (“chief executive officer”) managing a 50 million dollar budget has little if any understanding of basic accounting (or bookkeeping)

functions. The same can be said of many other important (and expensive) areas of district

operations such as fringe benefits, workers compensation, and investments.

A Compendium of “Best Practices”

The complexity of district management requires a substantial compendium of “best practices” to

insure efficient and effective management. This compendium, built on a verified knowledge and a validated standards base, should be a joint work of university, state agency, and professional

associations. This district management “bible” might merge university textbooks, state manuals, and professional association publications into a usable “best practices” text. The curriculum needs to be built on research, not anecdotal accounts or conventional wisdom based on flawed

professional practice.

Again, an extensive validation process is needed to insure “best practices” in the compendium are realistic, appropriate and inclusive for the various sizes and types of districts. The compendium topics might influence the curriculum of higher education courses, topics of state agency training, and evaluation standards for professional recognition. It should insure alignment between the

university programs, state agency, and professional associations concerns. These compendia of

best practices would serve as the base documents for the three tier recognition assessment.

Five Domains of Superintendent Executive Management

There are five domains of management preparation for superintendents (1) fiscal, (2), personnel, (3) support services (4) facilities, and (5) student services. Each domain can be developed into an instructional and performance module.

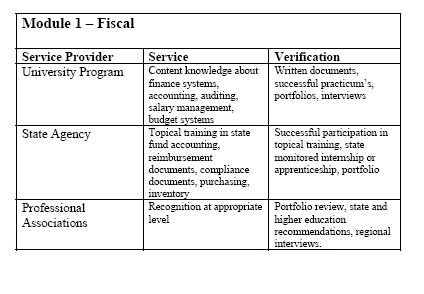

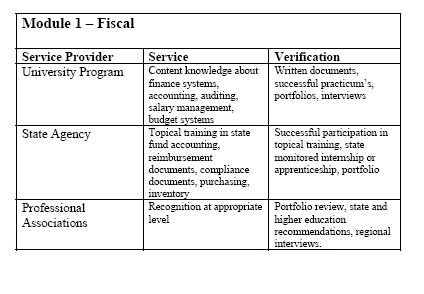

Module 1 – Fiscal

This critical module is focused on planning and managing the finances of school districts. The

role of the university based program should be to disseminate content knowledge about state

financing, taxing systems, budgeting systems, basic contract law, risk management programs, and structures of salary/wage management. This probably should be a 9 or 12 semester hour course

sequence in finance, budget, and operations management. Practicum and field experience hours

need to be required for students to experience first hand fiscal, budget, and operations systems at work in “model” school districts. Importantly, the course content (if possible) would extend

previous learning at the master’s (principal licensing) level. An example is “budgeting at the

building level,” a common content area in many master’s programs in educational administration.

The state role should be to provide specialized training (example being state accounting manual procedures) introduced in the university fiscal sequence augmented by practicum and field

experience contacts. Other examples would be requiring students to attend state agency sponsored workshops and training sessions focused on implementing and managing district management

programs in inventory, material distribution, fund accounting, auditing, and purchasing. The

participation might be kept in “professional portfolios” containing specifics of the training

(objectives, hours, content etc.) and of course the performance level of the participant.

Every state has very specific requirements on how these management functions are to be

performed and accounted for by local districts. Most states have already learned the best way to achieve management uniformity is through agency sponsored workshop and training sessions.

Hopefully, state agencies feel participants in these state sponsored training sessions perform

better if they already have received baseline content knowledge in prior higher education

coursework.

An excellent example is the state of Washington’s practice where the state auditor general directly audits the finances of school districts. Districts reimburse the auditor general’s office for these costs and in return receive excellent staff training in how the state desires districts to maintain fiscal records, control budget processes, and insure proper accounting practices. Superintendents many times receive the same training from the auditors as the district bookkeepers and clerks.

Internships and Apprenticeships.

Once a student has completed a 9 or 12 semester hour sequence and met state requirements in

specialized management curricula, a 2 year internship or 1 year “apprenticeship” in a district

central office should be required for licensing and nomination for professional recognition. A

comprehensive internship would be planned and sequenced “on the job training” woven into the

student-administrators “normal” working day as principal or central office administrator. This on the job internship would be supervised by the district superintendent and a university faculty

member.

A 1 year apprenticeship in executive management would involve at least 25% to 50% time release.

Internships would qualify applicants for initial recognition subject to further training. A

completed apprenticeship would qualify applicants for “full” recognition. The most intense part of the internship and apprenticeship would be in the area of fiscal, budget, and operations

management.

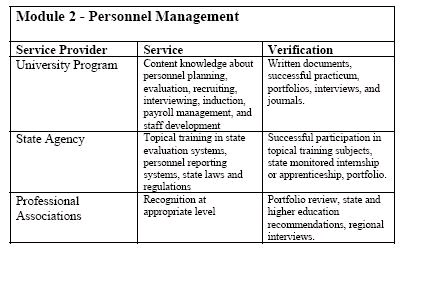

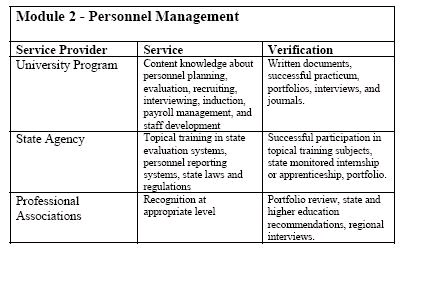

Module 2 Personnel Management

In this module, 9 semester hours of university course content would be required to provide

essential knowledge of personnel practices such as managing recruitment, evaluation, induction, and staff development programs. Three semester hours need to be required in personnel operation management areas such as fringe benefits, safety, and collective bargaining contract management.

The last 3 semester hours need to be an advanced school law class focusing on legal issues

particularly related to various types of contracts affecting staff and students.

As in Module 1, students need to be constantly required in practicum hours to observe and

participate in district based personnel programs. Again, much of the content in this module is

related to some content at the master’s level. Again, attention should be paid to sequencing

master’s degree (principal licensing) and superintendent preparation.

The state role in this module might be the same as in Module 1. Similar to Module 1, internship or apprentice hours need to be spent in the personnel office or division of a school district. In the private sector and in schools of business, the training of personnel managers is a graduate degree enterprise. Again, an internship needs to require release time. The state, as in Module 1, might develop a battery of “check” tests for students to pass in each of the personnel management

specialties before being eligible for review by a professional “personnel” association.

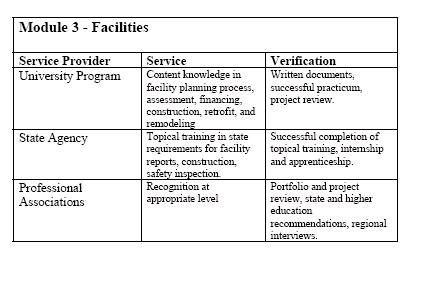

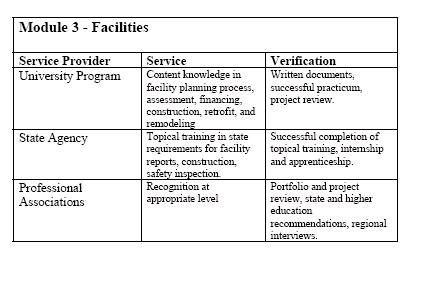

Module 3 Facility Management

The essential content of this module might be taught in a 3 semester hour course supplemented by practicum hours working in a local district on a school facility planning project. This would

include facility assessment, educational specifications, bonding issues, bond campaigns, and

management of existing facilities.

The state role in Module 3 might be specialized training in state sponsored facility construction programs, rules and regulations applying to facilities, and required safety programs. Again, the state might develop a series of check tests to insure mastery of content in these areas prior to recommending to a professional group for recognition.

Creating a training module in facility maintenance could easily be coordinated as most

superintendent trainees are either practicing principals or in central office roles.

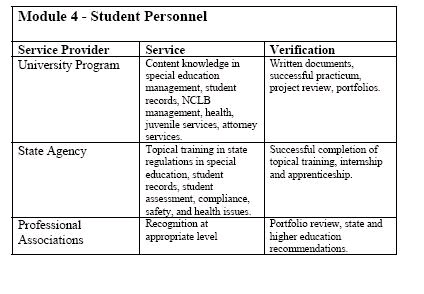

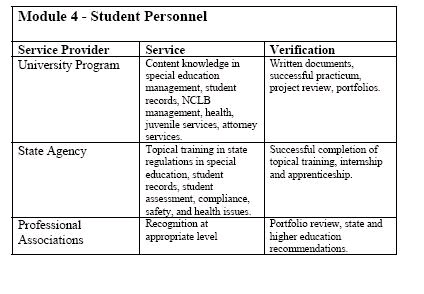

Module 4 Student Personnel

The content for this module might be contained a 3 semester course in the university program

reinforced by practicum experiences in school districts. Experienced principals and central office administrators often receive training at the master’s level or via on the job training in some this area. In this module special attention must be paid to the superintendent’s role in managing

district special education programs.

The state role is again to provide needed specialized topical training and develop a series of check tests for students prior to being forwarded to the professional association for recognition.

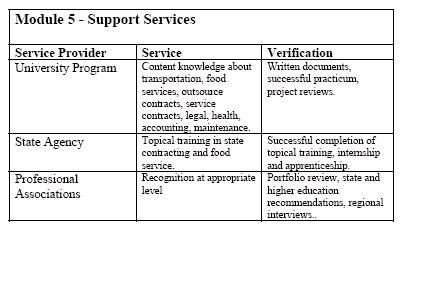

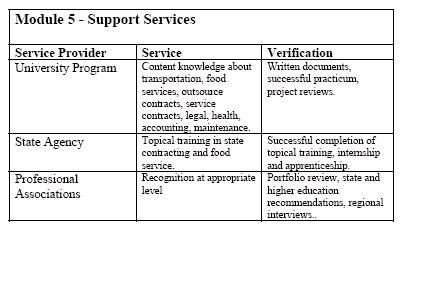

Module 5 Support Services

University based course hour requirements may not be required, but extensive topical training

sessions should be conducted by the state agency to insure prospective superintendents possess

sufficient knowledge in state regulations about busing, transportation, and out sourcing services.

The agency training should be supplemented by “practicum” hours in a local district with hands

on experience in bus scheduling, completing reimbursement forms, food inventories, safety, and

other relevant experiences. State agency developed check tests again would be administered to

students.

Table 3 provides a tentative outline of a superintendent management training structure. The scope of the training involves many more classroom hours and in field placements. The result will be

more costs to students, districts, and states. However, the payoff would be in higher levels of superintendent job performance and in the long run, provide a better school system.

Conclusion

Superintendent Management Program and Profile

At the conclusion of the university based courses and training provided by the state agency, each student could present a composite profile illustrating content learning, experiences, and

demonstrated competencies attested to by state agency tests, university based tests and assessment and feedback from district superintendents. This broad based assessment should be sufficient to convince school boards and communities that a superintendent is competent to manage district

fiscal and physical resources.

Fortunately, most of the management training needed by superintendents is assessable, as there is a right way and a wrong way to perform a task. In brief, it is a measurable type of training at the pre-service and in-service level.

The principal challenge for a state to develop and implement a superintendent management

training program will be to:

1. Align efforts between higher education programs, professional associations, and the state

agency.

2. Require districts to provide release time for training, internships, and apprenticeships.

3. Provide incentives for principals and central office administrators to enter a superintendent training program.

1. Establish a program to continually update and monitor the skills of central office

administrators already recognized.

References

American School Board Association/National School Board Association. (2000). Roles and

responsibilities: school boards and superintendents. Arlington: American Association of School

Administrators.

Callahan, R.E. (1962). The education and the cult of efficiency. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Council of Chief State School Officers. (19