systemic issues.

When individuals consider leading a school, it is important to note the relative importance of the many activities that come in a school day. Value in leadership means defining what matters most so that all can begin to understand what the business of school is. As individuals articulate the core values, the guiding and philosophical principles, then all decisions can emerge from a shared belief. The synergistic effect is that they can begin putting their energy toward specific values, avoiding the ad hoc decisions characteristic of many schools. What the student, teacher, leader, and community see reflected in the activities of the school is a value-driven institution with a vision for where it is going rather than an event-driven body. Just as with value in art, core values speak to all other elements of leadership. When done well, core values become the guiding

principles for all decisions and help create school space characterized as a place for authentic learning and caring.

In watching the students and teacher work together one trait consistently emerges as essential to a caring and authentic school: Empathy. Empathy can become value in that it represents a guiding

principle for the school culture. Empathy is that interpersonal quality that allows one to know the feelings of another (Kelehear, 2001; 2002). As students work with each other, as teachers work

with the students, and as the principal assists the teacher, the level of empathy present defines the qualitative relationship. And at the same time, the participants cultivate a sense of caring in the relationship as they began to understand the commitment in working together toward shared goals.

In as much as caring becomes a part of the school climate, the relationships become more

substantive and paying attention to each other becomes the order of the day. A process by which we can begin to shape a positive school culture might begin as school based leaders realign the role of four key players in the school day: the student, the teacher, the leader, and the curriculum.

Given the powerful influence on standardized assessments, federal mandates, and state-level

oversight, it is easy to reduce students to input/output items rather than see them in their

humanity. In his book Schools Without Failure, William Glasser (1969) emphasizes that allowing

grades to create an incentive for learning has, in fact, a contracting effect on what is learned. The more that grades, and by extension standardized tests, are emphasized the more that students want to know what is exactly on the test, and only those items on the test. Students come to believe that any other information can become an obstacle or a distraction to getting the grade, and thus should be ignored (p. 65). Effective school leadership will recognize that there is a role for grades and standardized testing. Indeed, they can help provide accountability for learning certain bits of information. But to rely solely on grades and traditional assessments is painfully shortsighted.

School based leaders can build a school culture that shines light on authentic student learning and staff professional growth. One way to construct such a climate is to place emphasis on what Ted Sizer (1992), in his book Horace's School, calls exhibitions. This type of assessment helps

encourage students to bring together facts and basic learning to create a new understanding– what Mortimer Adler (p. 29) called maieutic expression. A word of Greek origin, maieutic is loosely

translated as "giving birth." Just as an artist might be able to use the elements of art to paint a still life, it is the artist's use of those "skills" and the simultaneous interpretation of that object through experience and feelings that can give birth to a new perspective, a new understanding, a deeper cognition (Eisner, 2001). Similarly, other aspects of the curriculum could have the same

consequence.

School leaders and teachers must help students come to command facts and information, the kind

of information that is readily assessed through pencil and paper tests and standardized

assessments. Quickly, however, students begin to use the newly acquired information in

applications of the concepts through repeated practice and coaching; just as the artist begins to command the elements of art. Although many very good teachers might guide students to this

level of mastery, this is not enough. Through demonstrations, exhibitions, or other public forums, teachers should encourage students to create a new, deeper understanding, a maieutic expression.

The student's knowledge and understanding takes on what Eisner (1994) calls "a social dimension in human experience" (p.39). But teachers and students will only be able to do such authentic practice when the environment in general, and school leadership in particular, supports such

practice.

In a recent study of an arts magnet school (Bender-Slack, Miller, & Burroughs, 2006)researchers observed teaching practice in the standard curricular areas such as mathematics, English, social studies, and science. The researchers also followed the students to the classrooms for visual and performing arts. The purpose of their observations was to ascertain the degree to which an arts-infused curriculum was being implemented. The observation and data collection were conducted

in an art magnet school; the same type of place that one might think that arts-infused practice would be the norm, not the exception. To the surprise of the researchers, teaching practice among the core subjects areas remained traditional (i.e., teacher centered, lecture formats, seat work) and void of arts-infused practices. Similarly, the art teachers rarely embraced the standard curriculum in their delivery of instruction. Keeping in mind that the mission statement of the school

emphasized an arts-based, multi-disciplinary approach to learning, the researchers discovered that the school had changed leadership several times in the previous five years. The message for the researchers was clear, where leadership fails to support innovative practice for teachers and

authentic performances for students then leadership could not expect for the school to be any

different than one that might be characterized as unimaginative and traditional (Bender-Slack,

Miller, & Burroughs, 2006).

Understanding the teacher's role in developing authentic learning experiences is essential to

supporting a school culture focused on teacher and student learning. The traditional view that the teacher is the conveyor of knowledge and truth is only partially correct. Newmann and Wehlage

(1995) and Newmann, Marks and Gamoran (1996) assert that students learn best when teachers

are engaged in authentic pedagogy design and provide learning experiences that: 1) encourage

students to build new knowledge, 2) embrace and support disciplined inquiry, and 3) have value

beyond the school setting. Creating such authentic pedagogy supports knowledge that students

believe is more meaningful and relevant than what might be expressed in traditional pencil and

paper tests that seek rote answers to prescribed questions. This position is not to suggest that knowledge memorized is always an undesirable product of schooling. The practice alone,

however, is wholly insufficient. Rather, and in keeping with a position supported by Dewey (1934) and more recently embraced by constructivist philosophy (e.g., Lambert et al., 2003), when

students begin to engage subject matter in meaningful ways, then they begin to construct meaning of and establish value in the school curriculum. The ownership of problems in the curriculum

moves from teacher to student. In other words, instead of a teacher presenting problems to

students to be addressed, students move to engage problems (i.e., sources of dissonance) that

compel them to resolve apparent inconsistencies in their previous understanding. An important

part of this authentic perspective posited by Newmann and Wehlage (1995) and Newmann, Marks

and Gamoran (1996) is that authentic pedagogy supports meaningful, personal, and private

reflection on the part of students and teachers alike. In essence, they are addressing qualitative relationships and fine grained distinctions (Eisner, 2002) between what they knew to be true

before the learning experience compared to what they are coming to know based on the personal

construction of new knowledge. This intrapersonal reflection then becomes part of a classroom

that embraces the aesthetics of learning. As students continue to seek meaning and purpose in the new knowledge, then they move to open discourse with their peers and teachers.

In order for teachers to encourage authentic expression from student and for teachers themselves to experiment with what works for different types of students, there will need to be a special type of leadership. The role of the principal is to protect jealously the learning environment, to guard the classroom as a safe place where teachers and students may take risks, and to promote an

atmosphere of openness and authentic communication. Embedded throughout this vision for

leadership is the pivotal role of trust (Kelehear, 2001).

Through open communication, shared decision making, and mutual respect, the school will model

the characteristics of a pluralistic, democratic society. There will be many teaching styles; ideally, as many as there are different learning needs. The leadership will celebrate those differences

while maintaining high expectations for student learning. Allowing teachers to utilize different techniques does not free them from responsibility for student learning. In fact, the opposite is true.

In as much as the principal allows for teachers to choose strategies for student learning, then the principal can hold those teachers responsible for what happens in the classroom. The question to the teacher will not be "Did you teach well today?" but rather, "Did the students learn today?" As Sizer (1984; 1992) reminds us, if the answer to the second question is “yes,” then the answer to the first question is “yes.” Said differently, one cannot have taught well in the absence of student learning!

Authentic leadership would seek to construct a context where the teachers and principal work

together to form a school culture that is focused on student achievement and engaged citizenship.

The teachers and principal would be clear about student achievement and teaching excellence as

essential core values. They would attend only to those activities that support and foster student and, as an extension, teacher successes (Patterson, 1993, p. 37-52).

The nature of leadership would be such that it too is not a prescription. Rather, leadership in the authentic school would celebrate children's uniqueness and the art of teaching. Similarly, teachers and principal alike would understand that leadership is in itself an artwork under construction. Just as the principal celebrates and promotes the uniqueness of teachers, the teachers would likewise support and challenge the principal to be open, authentic, and a risk-taker in making decisions that support the core values of the school.

Authentic learning spaces emerge when leaders create opportunities for teachers and students to reflect on experiences in qualitative ways. Central to the construction of such a space requires leadership to design a curriculum in which all the disciplines are embraced as complementary and supportive and not in competition for space and budget. In essence, successful school management becomes a process of providing opportunities for meaning-making for teachers and student alike.

The final assessment of our schools might be as Eisner (2001) states, “It’s what students do with what they learn when they can do what they want to do that is the real measure of educational

achievement” (p. 370). If our students do not continue after school the things about which we talk in school, then we may have failed them.

In today’s schools, leaders are confronted with the harsh reality that effective teaching and

leadership involve experiment, reflection, and refinement and that effective school based

leadership supports such practices. Today’s school cultures must be places that allow teachers and leaders to recognize their own humanity and that of their students (Palmer, 1998). Both teachers and students ought to be allowed to fail and leaders must provide for them support in their

mistakes. School leadership can begin, thus, to acknowledge that out of the diversity of ideas, great wonders can emerge. Indeed, Steinbeck (1955) reminds us, "teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit” (p.7). Today’s school building leader must have the strength of will and the commitment to doing what matters most: attending

to the needs of the children. The best way to achieve this goal is for school leadership to allow for the art that is teaching where authentic learning and caring for each other carry the day. Being clear about value and the light it sheds on practice is indeed a crucial part of successful school based management.

Element #3:

Shape: Two-dimensional area

The Artist’s View:

A shape is a two-dimensional area that is defined in some certain way. By drawing an outline of a circle on a piece of paper, one has created a shape. By painting a solid red square, one has also created a shape. Shapes may be either free-formed or geometric. Free-form shapes are uneven and irregular and usually promote a pleasant and soothing feeling. Geometric shapes on the other hand are stiff and uniform and generally suggest organization and management with little or no

emotion. Shape tends to appeal more to viewers’ minds rather than to their emotions.

ISLLC Standard #3: A school administrator is an educational leader who promotes the success of

all students by ensuring management of the organization, operations, and resources for a safe,

efficient, and effective learning environment.

A Leadership Perspective:

Schools have a shape, a smell, a look, a feel. As we imagine our elementary school days, we create physical images that capture our learning experiences. Similarly, as we walk into the elementary school just before lunch to smell the bread cooking in the dining hall, we are taken back to some of our favorite (or maybe not so favorite) memories of schooling. Whatever the quality of those memories, they are certainly vivid. We watch the big yellow school bus traveling down the road

and wonder about the children in that lovely “monster” of a vehicle. These images are not about instruction. They are about the other things that inform our memories and have deeply affected

our lives. Even though they are not instruction, they are important to the successful school. They are the shape of schooling.

Management is the shape of schools. We manage budgets, discipline, community relations, and

personnel. These are not the things that should be our focus in schools but they are exactly the matters with which we must deal so that we might teach children. And, the degree to which a

leader can handle aspects of time management, scheduling, random but daily details, personnel

management, parent conferencing, and community relations will determine the level of success

for the students at that school. Of the management details, supervision of personnel is the most rewarding, demanding, and exhausting. Successful leaders find ways to be instructional leaders by offering supervision, staff development, remediation, and when necessary termination. But during the whole process of management, leaders struggle to balance being compassionate and supportive with being clinical and direct with personnel. Both sets of skills are necessary, but it is the rare leader who can do them both well. Effective leaders understand how to shape the modes of

management to support the business of student learning.

Recently, while involved in staff development for assistant principals, it became clear to the

author that the systemic configuration in the schools inhibited, or prohibited, the proper

application of leadership functions. Put bluntly, school leadership has assumed so many different roles in the building that some leaders felt they were not doing any of the jobs very well. In fact, based on recent research with practicing assistant principals (Kelehear, 2005) the author and

participants reconstructed the leadership position so that myriad responsibilities might be

separated into two categories, for two different positions. Instead of one position in charge of both management and leadership, there would be the Manager of Programs (MP) for administration

and the Instructional Leader (IL) for instructional supervision. Being in charge in today’s schools continues to be a daunting task. Given the competing demands of federal mandates, state

assessments, standardized-testing schedules, shrinking revenue streams, and the like, it is no small wonder that children and teaching somehow get lost in the shuffle.

It is clear from the literature (Sergiovanni, 1999; Smith & Piele, 1989; Glickman, Gordon, & Ross-Gordon, 2004; Sergiovanni & Starratt, 2002; Fullan, 2001; Starratt, 2004; Robbins & Alvy, 2003) that principals are called upon to do a myriad of jobs. It is a challenging task for principals to offer instructional leadership and also manage the other competing responsibilities. In much the same way as a teacher must be a successful manager of classroom behavior in order to be able to teach, the school leader must be able to manage the school so that instruction can take place. But to ask one person to manage all the business of schooling and also to conduct instructional

supervision might be an unrealistic expectation. In working with 14 administrators, the author

began to imagine that by separating the instructional supervision function from the principal’s responsibility, then maybe another teacher leader could more fully supervise instruction in our schools (Kelehear, 2005). The role of instructional supervision would rest with someone whose

primary responsibility was instructional development. Managing all other affairs of schooling

such as budgets, parent conferences, and discipline would reside with the principal’s position. The Manager of Programs (MP) was responsible for all matters of school governance and management

with the exception of instructional leadership.

The Instructional Leader (IL) would conduct all instructional programs relative to evaluation,

supervision, induction, remediation, and instructional staff development. This job would carry

with it a supervisory supplement that would recognize the lead teacher’s supervisory

responsibilities. The school would have an instructional committee whose responsibility it would be to select an IL who may or may not be a member of the committee. The IL’s appointment

would be 3 years. The IL would function as a part of the instructional committee but leadership within the committee would reside with a different person. One way to imagine the organization is to imagine an elected school board with an appointed superintendent. The committee will have

representatives from grade levels for elementary schools or from subject areas for high schools.

Middle schools would have instructional committees drawn from teams.

For matters relative to evaluation, the IL would have the primary responsibility for making

“judgments concerning the overall quality of the teacher’s performance and the teacher’s

competence in carrying out assigned duties as well as provide a picture of the quality of teaching performances across the professional staff” (Nolan, 2003). These data will be collected as part of the teacher’s overall evaluation in terms of retention, tenure, and promotion. The actual process for making employment decisions is described later in this paper.

Within the context of supervision, the goal of the IL is to offer instructional support for teachers throughout their professional career paths. Novice teachers might receive close-ordered coaching to help through the stresses of being new to the profession. Tenured teachers might receive

support in the form of instructional development and experimentation. End-of-career teachers

might receive requests from the IL to share expertise with others or to take on staff development responsibilities. At whatever the career stage, the nature of the instructional support will be in the form of developmental supervision or mentoring.

Research on mentoring emphasizes that the direction and content of instructional development is a shared responsibility of both the novice teacher and mentor teacher (Glickman, 2002; Reiman,

1999; Reiman & Theis-Sprinthall, 1993). Through collaboration and coaching the pair of teachers observe each other, share reflections on experiences, and develop professional development plans.

Although during the early stages of the professional relationship, the mentor will likely assume a dominate role; over time the nature of the relationship will shift responsibilities from the mentor to novice (Gray & Gray, 1985).

A key function of the IL is to identify, develop, and supervise a cadre of successful teachers who are trained in developmental supervision and mentoring. The IL will be the lead mentor and will offer support and guidance to the cadre and will also substitute in cadre classes when the mentor is conducting observations or conferences. Each mentor will provide reports to the IL regarding

dates of mentor contacts, the nature of the observation, and any issues that the IL might need to address. Because of the need for confidentiality and trust in the mentoring relationship, care will be given not to offer specific details of the mentor’s contacts. The mentor’s contacts will be

formative in nature. Differently, the IL will conduct summative observations and evaluations of teachers for employment decisions. The IL will offer summary reports and recommendations to

the MP and those reports would become a part of the teacher’s personnel file. The MP will also

make recommendations, again for inclusion in the personnel file, for employment based on

teachers’ performances of non-instructional responsibilities (e.g., bus duty, lunchroom

supervision, committee participation, attendance). The instructional committee will receive

recommendations and will offer its recommendation for employment as well. In effect,

employment decisions then come upon a three-vote decision: one vote from the IL, one vote from

the MP and one vote from the instructional committee. Based on the three reports, the MP will

construct a letter to the Director of Personnel that summarizes the findings and will offer a

recommendation regarding the continuing employment status of the teacher. Both the MP and the

IL will sign the letter. Any disputes or dissenting opinions will also be submitted, as attachment, to the Director of Personnel for inclusion in the personnel file.

Although the IL would be responsible for the personnel evaluation component, the instructional

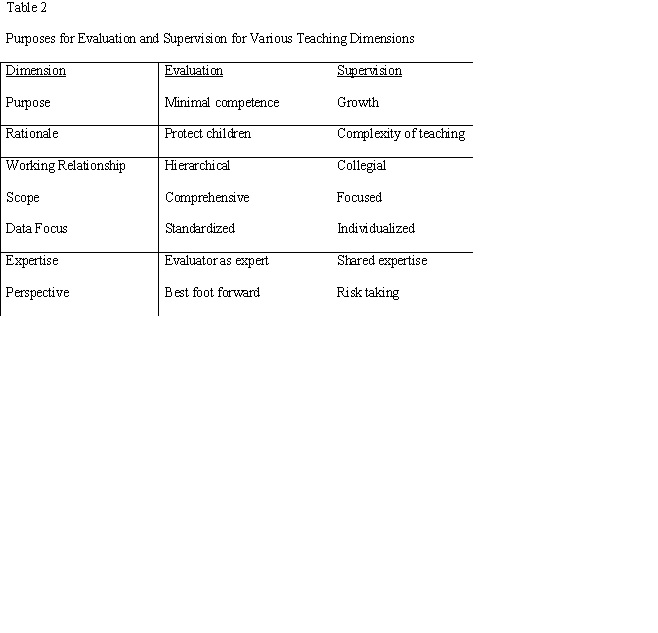

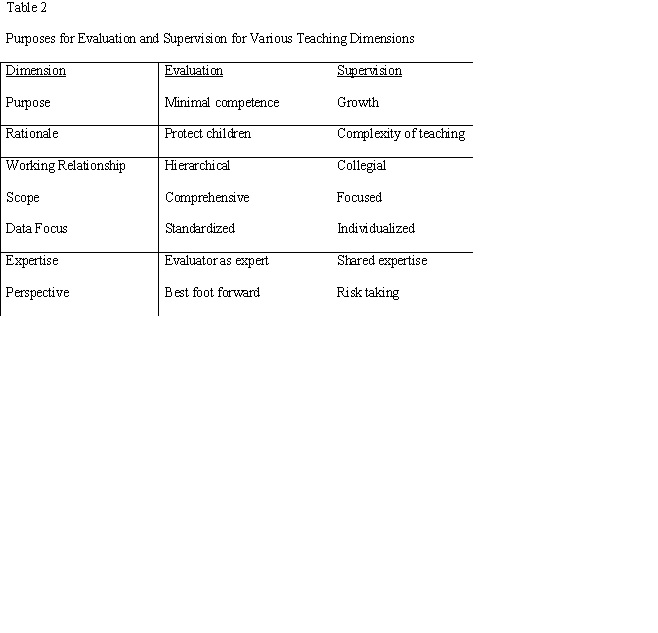

committee and mentors would engage in supervision exclusively. The group based the distinctions of what constitutes evaluation vs. supervision on Nolan’s (2003) work. According to Nolan, the

natures of evaluation and supervision are fundamentally and critically distinct within various

functions of the teaching experience [See Table 2]. Given a particular dimension, the distinctions between evaluation and supervision become clear.

It is in the form of mentoring as a supervisory practice that some of the more powerful benefits for teacher growth and development seem to emerge (Reiman 1999; Glickman, 2002; Pajak,

2002). Individuals who have a trained mentor are more likely to realize professional and personal growth than those who work alone (Vygotsky, 1986). This benefit is especially noticeable when

teachers are in new assignments or in new settings. Whether we are speaking about new doctors,

new teachers, new administrators, or new professors, a supportive colleague can help a novice

move to higher levels of effectiveness. Writing about medical school novices, Rabatin et al.

(2004) noted that a “mentoring model stressing safety, intimacy, honesty, setting of high

standards, praxis, and detailed planning and feedback was associated with mentee excitement,

personal and professional growth and development, concrete accomplishments, and a commitment

to teaching” (p. 569).

For public school teachers having a mentor is associated with professional growth and a sense of self-efficacy for both novices and experienced teachers. In working with veteran teachers, Reiman and Peace (2002) sought to “encourage new social role-taking, support new learning in effective teaching, encourage new complex performances in coaching and support conferences, and

promote gains in moral and conceptual reasoning. Significant positive gains in learning,

performance, and moral judgment reasoning were achieved” (p. 597). Mentoring had a

bidirectional benefit for both novice and mentor. The best plan for supporting instruction will require a position that is wholly, and singularly, focused on the processes of teacher development.

As a benefit to school cultures, mentoring in a developmental supervision model encourages

conversation among teachers. In conversation we begin creating a school community

characterized by sharing, supporting, and caring. It has become clear through research of

Noddings (2002), Palmer (1998), Starratt (1997), and others that when teachers and students work in a caring and supportive atmosphere, they are more likely to take risks, experiment, and attend to each other’s needs. It is just this type of collaboration that the process of mentoring can

encourage.

Form: Three-dimensional structure or shape; geometric or free

form.

The Artist’s View:

Forms are shapes that are three-dimensional and are either geometric or free form. In two-

dimensional works of art (that is, artworks that hang on a wall), artists use value on a shape to create a form. In other words when artists add value to the shape of a circle, the shape becomes a sphere and takes on the illusion of something that is three-dimensional -- a form. Today artists refer to light and dark areas of a work of art as modeling or shading. Very dark areas of forms tend to recede into the artwork where very light areas appear closest to the viewer. In three-dimensional art works such as sculpture, all shapes are forms because they take up space in three dimensions. True forms occupy height, width, and depth in space.

ISLLC Standard #5: A school administrator is an educational leader who promotes the success of

all students by acting with integrity, fairness, and in an ethical manner.

A Leadership Perspective:

The difference in management and leadership is the movement from shape to form, from two-

dimensional perspective to a three-dimensional one. Leadership in many cases is a matter of

perspective. Effective leaders find ways to recognize different perspectives in general through effective communication and more specifically through active listening. Truly gifted

communicators can discern surface messages and distinguish them from the very important, but

embedded, messages. What is the speaker saying? What is the speaker communicating? What is

the speaker feeling? The answers are often wide-ranging.

The form for effective school-based management comes as effective communication. In other

words, effective management requires one to be able to see individuals, events, and cultures from three dimensional perspectives. Communication has as its prerequisite trust. Without a sense of trust between two people, both in terms of content and confidentiality, there is little hope of meaningful conversation. An obvious example might be that if teachers trust their colleagues to work with them and not reveal their weak teaching areas to the general public, and certainly not to supervisors, then they might be more inclined to share deficiencies with colleagues. In so doing, teachers might be able to find help toward improving pedagogical gaps. If, on the other hand,

teachers do not have the confidence in others' genuine concern for their professional development, they will certainly not engage in conversation with