Alexander J. Wall Builds a Professional Institution, 1921-1944

A staff member since the age of fourteen, Alexander J. Wall had been Robert Kelby's assistant for more than twenty years and was therefore intimately familiar with the library and its holdings. Even more than his knowledge of the collections, it was Wall's personality and charisma that had the most impact on the Society. One biographer observed that "few people enjoyed a party with companionable friends more than he did" and that "this quality was a predominant reason for his success in life."[] Considering Wall's nature, it is not surprising that following his installation as librarian, the Society took steps to become both more open to the public and more active in issues of importance to a broader segment of its potential constituents.

One of the many successes of Wall's tenure was bridging the gap between the historical societies and the scholarly community, something that previous Society leaders had failed to accomplish. With a particular passion for preservation, Wall led historical society professionals in urging the federal government to establish a national archive. In addition, Wall's dedication to this cause led to his later involvement as one of the organizers of the American Association for State and Local History. Wall's interests were not confined to historical preservation; he also actively cultivated relationships with the academic community. In 1925, he established a $300 New-York Historical Society Scholarship at Columbia "to encourage further study and investigation in the field of history." Although the scholarship was discontinued due to lack of funds in 1933, it represented the first step in the Society's relationship with Columbia, a relationship that eventually led to Wall's appointment as an associate in history, teaching a seminar titled Resources and Methods of an American Historical Society. Wall's simultaneous roles as a spokesperson for historical professionals and as a scholar teaching at a respected university helped propel The New-York Historical Society into the mainstream of professional library and scholarly activity.

During his tenure, Wall encountered the natural contradictions faced by a library trying to serve both a relatively exclusive community (scholars) and the wider populace. Wall's efforts to resolve this tension emphasized the importance of education in bringing history to a broad audience. For the Society, this approach had both practical and philosophical implications. In 1928, the state legislature approved Wall's petition to modify the Society's act of incorporation to include language specifically recognizing its educational mission. This step was more than a legalistic gesture; gifts and bequests to educational institutions were not subject to state taxes. But Wall's motivation was not just financial; he believed strongly in the Society's educational responsibility. In an article published in the New-York Historical Society Quarterly in April 1938, Wall wrote, "Historical societies should have an important place in education. In the past we have failed to achieve this position primarily because we have been too ready to believe that historical investigation belonged to the few and that those who entered our portals treaded on holy ground. . . . But times have changed and people no longer have to knock at our doors for they should be open. And our work should be an inspiration to interest the many in the satisfying and unending joy of research and investigation."[] The Quarterly was one vehicle Wall relied on to "interest the many." Conceived by Wall primarily to publicize the work of the Society, the Quarterly enjoyed a solid reputation in the field of historical society journals. As its editor, Wall also used the Quarterly to publicize his position on issues of importance to the Society and to the profession, as well as to publish some of the library's treasures that were not appropriate for inclusion in more formal publications of the library's collections.[]

If the Quarterly was Wall's effort to take the Society to the people, Wall's educational programs emphasized bringing people to the Society. He and his assistant, Dorothy Barck, who was appointed librarian in 1942, shared a desire to encourage historical interests in young people. In 1945, Barck established two undergraduate internships in library training that were filled by students from nearby colleges and universities. Such programs, along with general encouragement offered to young readers, bore fruit early in the postwar period, when there was a noticeable increase in the number of undergraduates, high school students, and even grammar school students using the library. Barck wrote in the 1945 annual report that this trend was "heartily to be encouraged, and we welcome young people who are genuinely interested in research."[]

Wall's efforts to open up the Society did not go unnoticed. Dixon Ryan Fox, president of the New York State Historical Association and an outspoken critic of the Society under Robert Kelby, said that "the atmosphere of exclusiveness and self-content" at the Society had been dispelled not only by Wall's "intelligent sympathy" with all serious scholars but also by his "concern for popular education" and the fact that the Society "gladly welcomed school children and casual visitors."[]

Wall's leadership of the library moved the Society beyond the mistakes of the late 1800s and helped position the institution to play a more significant public service role. Still, that progress might not have been possible were it not for two other developments that helped make Wall's tenure a period of prosperity and professionalism: first, in April 1935, Mary Gardiner Thompson, daughter of David Thompson (the former president of the New York Life Insurance Company), died, leaving over $4.5 million to the Society between 1935 and 1942;[] and second, a reorganization of the Society's governance and management structure gave the Society an institutional framework commensurate with its increasing size and stature.

The Thompson bequest could not have come at a better time. In the beginning of 1935, "the wingless building was jammed . .. almost beyond endurance," and resources remained tight. With a limited endowment and only seven professional staff members, "there seemed little hope for the enlargement of [the Society's] activities or for the raising of the hopelessly large sum needed to complete the building."[] Furthermore, the Society's endowment was largely invested in real estate, and the Depression had made collection of rent and mortgage payments difficult.

The Thompson bequest, equivalent to $54 million in 1993 dollars,[] gave the Society financial breathing room for the first time in its history. More than one-third of the bequest—$1.7 million—was used to renovate the central building, build two new wings, and construct a fifteen-tier bookstack at the rear of the building. The remainder of the funds was placed in permanent endowment. Moreover, the completion of the building, which was closed for nearly two years, from May 1, 1937, to March 29, 1939, gave the Society's leadership time to reflect on its mission and policies. What resulted were several steps taken to professionalize the management of the institution.

One area that was badly in need of improvement was the cataloging, shelving, and classification of library collections. As was mentioned previously, the Society's cataloging and shelving had been inadequate even in the Second Avenue building. There had been little improvement since that time. When the library moved to the new building in 1908, books were shelved using the same system. In fact, "the card catalog, primarily accessible by author, was the same one instituted ... in 1859."[] The renovation of the central building and the reinstallation of the collections provided an opportunity for modernization.

In 1940, the Society adopted the Library of Congress classification system for new acquisitions and started a new card catalog that followed American Library Association rules. Though this step was an improvement, it created another problem: there were now two card catalogs, one for acquisitions made prior to 1940 and one for acquisitions made after that year. This dual system, along with the Society's backlog of uncataloged items, made it very difficult for users (and librarians) to access, much less comprehend, what items were in the collection. The fact that during the reshelving process, library management "discovered" a number of rare books for which there had been no records at the Society exemplifies this problem and makes one wonder whether similar discoveries might still be made at the Society.

Reorganization took place at a higher level as well. For its entire 122-year history, the Society had been a membership organization with an executive committee responsible for conducting its affairs. Participation by the membership had dwindled over the years, to the point that few members attended the meetings, and election of the Society's officers was effectively done by proxy. Given these circumstances, and the substantial endowment generated by the Thompson bequest, it was decided that the Society ought to update its governance structure to put it on par with its peer organizations.

On November 18, 1937, the last general meeting of the membership was called to approve a change to the organization's by-laws establishing a board of trustees and placing complete control of the Society's affairs with that board. Also approved at the meeting was a change in the chief executive officer's title from librarian to director. Although the responsibilities of the position did not change (the librarian had always run the day-to-day affairs of the Society), the change in title finally gave recognition to the fact that the Society was more than just a library. As director, Wall was now clearly accountable for the success of the museum as well as the library. In contrast to organizations like the Massachusetts Historical Society and the American Antiquarian Society, which had divested themselves of museum collections and were focused on their roles as research libraries, the Society chose to continue to pursue the challenging objective of supporting both endeavors.

The Society had never been thought of as having two distinct parts. Since its inception, it had been organized as a single entity. Although the original by-laws of the Society mentioned that the librarian was to be responsible for the museum (or "cabinet," as it was called), the cabinet was considered to be just another part of the library and had always been of secondary significance.

With the addition of prized museum collections in the late nineteenth century, however, the museum side of the Society grew in importance. That trend continued as more important paintings and museum artifacts were added to the collections, to the point that by the late 1930s, Wall believed that the library could not survive without the museum. Writing in the Quarterly, Wall asserted that the "scholarship part of the historical society's work would be likely to have a bare cupboard if not coupled with a popular museum and a program of public education."[] He went on to suggest that exploiting the fundraising potential of the museum collections and historical artifacts was "the best way to gain financial support as we are judged by those whose fortune it is to endow, by what we do for the people as a whole, and not by the service we render scholars alone."[]

Wall recognized the importance of the museum; he also knew that operating a popular museum required different management processes than running a scholarly library. In 1937, Wall created a separate and distinct museum department, thus allowing the museum to pursue its mission free of entanglements with the library. In addition, the realignment gave Wall a structural mechanism for evaluating and making resource allocation decisions between the two entities. But balancing the two was a complex task that required the attention of a highly skilled manager. Wall was, for the most part, successful; but as is so often the case, the solution to one problem created another. The programs and operations of the Society could be compromised if it were ever without the forceful leadership required to balance the competing demands of the two departments.

The story of Alexander Wall's tenure and its successes would not be complete without mention of George Zabriskie, who served as treasurer of the Society (1929-1939) and then president of its Board of Trustees (1939-1946). As treasurer from 1929 to 1939, Zabriskie oversaw a period of enormous highs and lows in the Society's finances. During his tenure, he managed to hold the Society's real estate investments together during the Great Depression and then prudently invested the Thompson bequest. As noted earlier, the Thompson bequest was used both to pay for the construction of the new building and to establish the Society's endowment.

During Zabriskie's tenure as board president, the Society accomplished a great deal in a short period of time. Within approximately two years, the building was finished and renovated; the by-laws were changed, establishing a self-perpetuating board of trustees; and a distinct museum department was established. In addition, the Society's endowment, which had grown to $4.3 million, comfortably supported its operating budget. By 1943, investment income had grown to $201,000, an amount far in excess of the Society's total operating expenditures of $168,000.[] It is safe to say that these developments would not have been possible without a close working relationship between the board and the professional staff and, in particular, Zabriskie and Wall.

The closeness of Zabriskie and Wall's working relationship was evident when, after the Society closed for construction in 1937, the two men embarked on a European trip (at Zabriskie's expense) to research the best uses of natural lighting in gallery spaces. They visited fifty European museums and returned with many ideas that were implemented in the new building. When the building's new skylights were installed, they were considered the best in the country, and museum executives frequently came to the Society to study them.[] The Zabriskie-Wall partnership was a high-water mark in the Society's history that would prove difficult to attain again.

On April 15, 1944, Alexander Wall died at the age of fifty-nine. The progress made at the Society during his tenure, particularly after the Thompson bequest, had established the Society as a leader among historical societies. The significant income from the endowment had made it possible for the Society to expand its operations; between 1935 and 1943, total operating expenditures increased 163 percent, from $64,000 to $168,000.[] Much of these increases came in the form of increased compensation and the hiring of additional staff. Total compensation and benefits, the Society's largest expenditure category, grew 215 percent, from $40,000 to $125,000, over the same time period. Part of this figure was Wall's salary, which at the time of his death was $16,000 ($157,000 in 1993 dollars). The Society's growth during Wall's tenure made his position one of the most prestigious historical society directorships in the country.

The Difficult Postwar Years of R.W.G. Vail, 1944-1950

During the Society's first 140 years, it had always hired an internal candidate as the new chief executive (who had been the librarian through 1938 but was now the director). For the first time in its history, the Society looked outside for a replacement. Why the Society conducted an outside search cannot be known, but there are several possible explanations. One explanation could be that it was an indication of the success of Alexander Wall in professionalizing the Society. Another possibility might be that the Society needed to find a leader of high prestige and stature—someone to enhance even further the esteemed position die Society had staked out for itself. There is yet another possible explanation, dependent on a certain degree of speculation, that the Society searched externally because the most qualified inside candidate was a woman.

Over the course of the Society's history (except for the relatively brief period during which Robert Kelby chose not to be librarian), the assistant librarian had always ascended to the role of librarian. To carry on that tradition within the new organization structure, the likely choice for the position of director would have been the standing librarian. But Wall, who was ahead of his time in so many ways, had entrusted the position of librarian to Dorothy Barck, the first woman in the history of the Society to hold such a high office. Even though Barck had served the Society for twenty-four years, she was not chosen to be the director. This break from the traditional succession process, for whatever reason, altered the power balance among departments within the Society, a development that would have repercussions in terms of both leadership and direction in the years to come.

The job of leading the Society had become complicated. Balancing the sometimes competing demands of the museum and the library, in terms of both finances and focus, represented a formidable challenge. After a two-month search, the Board hired Robert W. G. Vail to succeed Wall as director. By hiring Vail, the board signaled that the library, not the museum, was of primary importance, for Vail's professional background was exclusively as a librarian.

Vail came to the Society from the New York State Library, where he had served as librarian since 1940. His previous experiences included a two-year stint as the librarian at the Minnesota Historical Society and nine years as the librarian at the American Antiquarian Society. Did Vail's experience prepare him for the complexities of the Society and for managing its two valuable and growing collections? Perhaps not. Vail's primary focus appears to have been scholarship and the publication of collections, not administration. In The Collections and Programs of the American Antiquarian Society: A 175th Anniversary Guide, a single sentence is devoted to Vail's nine-year tenure from 1930 to 1939. It reads: "While in office, he [Vail] completed Sabin's Bibliotecha Americana (volumes 22-29), picking up where Wilberforce Eames of the New York Public Library had left off."[] Further, LeRoy Kimball, the Society's president, wrote that Vail "just can't help delving and writing, and there is reason to believe he will be most unhappy unless he keeps his hand in way up to the elbow. For him, research and writing are part of his days— and nights."[]

The professionalization of the Society in the Wall era set the stage for growth, but effectively managing that growth would have posed a formidable challenge for even the most highly skilled professional administrator. For Vail, the difficulty of managing the Society would be compounded by a need to balance his passion for research against the growing demands of a job that would require strong and focused leadership.

The years immediately following World War II turned out to be difficult ones for the Society. Revenues, which were highly dependent on the return from investments, were not growing at the same pace as expenditures, and in 1945 the Society ran a deficit. For an organization that was becoming accustomed to annual surpluses, the late 1940s were a period of forced self-assessment. In the annual report of 1946, Vail lamented that income was lagging and that there were insufficient funds to give staff the raises they deserved. As a cost-saving measure, Society management cut the workweek by five hours. In 1947, the revenue woes continued. Vail wrote, "In order to improve our service to scholars... we should have an additional annual income of $50,000 for the next 20 years to use in building our collections and cataloguing our treasured possessions."[]

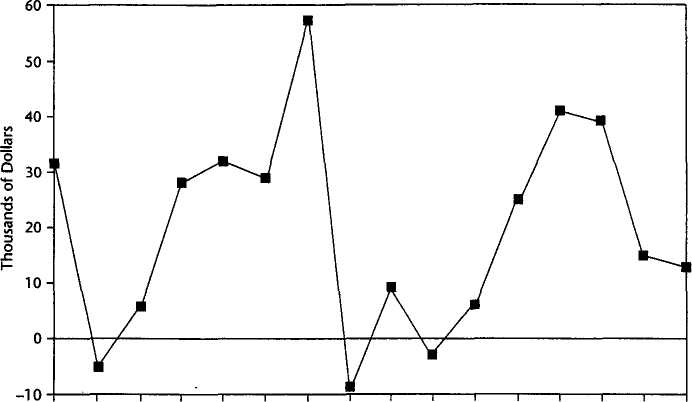

A close look at the Society's finances during this period highlights the very different mind-set that existed during this era regarding deficits. Put simply, deficits were not to be tolerated. Instead of waiting for mounting deficits to force cuts, management made cuts to avert deficits. Figure 3.1 shows the Society's operating balances during Vail's tenure. After an initial deficit in 1945, the Society actually ran moderate and increasing surpluses in the years between 1946 and 1950.

Nevertheless, the fear of recurring deficits exerted discipline on the Society. In the 1948 annual report, Vail wrote: "Although we have weathered this year successfully, we fear that our future may be endangered unless we economize and so it has been found necessary drastically to cut our budget for the coming year." These budget cuts resulted in the elimination of five positions, including the curator of paintings and sculpture.

While pressures were mounting to gain control of the Society's finances, efforts were still being made to expand the scope of services the Society offered. One reason for this expansion was the return from war service of Alexander Wall Jr.,

FIGURE 3.1. OPERATING SURPLUS/DEFICIT, 1944-1959.

1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 Source: New-York Historical Society annual reports; see also Table C.3-2 in Appendix C.

the son of the late director. In 1946, he returned to his position as director of education and public relations; shortly thereafter, he was named assistant director of the Society. This development, which placed Wall next in line to succeed Vail, was at least partially the result of the power vacuum created when Dorothy Barck, the librarian, was not named either director or assistant director.

With the assistant director now representing education, not the library, as had traditionally been the case, the Society's education initiatives became an area of increasing emphasis. In the annual report of 1946, the outgoing president of the Society said the Society hoped, even in the midst of a very difficult economic environment, "to continue and to expand its efforts to make American history a vital part of the education and entertainment of the young people of our schools." Special programs brought thousands of elementary school students to the Society, and a traveling exhibit toured New York City high schools. The Society tracked and proudly reported the exposure it received from these initiatives; the annual report for 1946 noted that approximately eighty-six thousand students were introduced to the Society through the traveling exhibits during the course of the year.

The Society's expansion resulted in small deficits in 1951 and 1953. Under pressure to balance the budget, Vail reminded the board of trustees of the need for more income. He emphasized the need for funds for the purchase of new materials for the library, museum, and art gallery and pointed out that if the Society hoped to give "adequate service" to its "ever-increasing clientele," it "must have better salaries and more trained people."

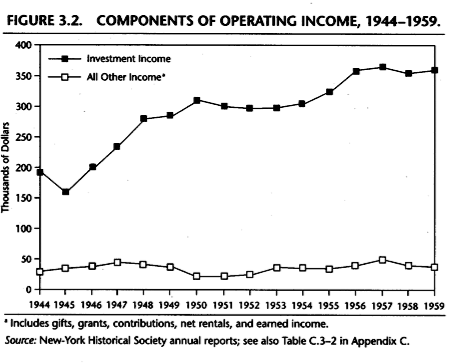

Despite Vail's pleas, there is little evidence to suggest that significant efforts were made to develop new revenue sources. The Society remained almost exclusively dependent on investment income to fund its operations (see Figure 3.2). For example, although the education programs provided a clear public service, no effort was made to involve the city or state government in defraying the cost of these services. Neither was there any attempt to raise private contributed income.

The expansion of the education department complicated further the task of managing the Society. Already wrestling with the demands of coordinating the museum and library, the Society's management now had to fold a more aggressive public education program into its overall mission. From the annual reports of the late 1940s and early 1950s, it is not entirely clear that the leadership of the Society was comfortable with integrating these purposes. For example, at the same time that initiatives were under way to introduce thousands of schoolchildren to the library through tours run by the education director, Vail, at a meeting of New York City librarians in 1948, "called for the elimination of student and popular use of research libraries."[] In each successive year, the Society reported on the successes of the school education program and the growing number of students coming to the Society, even while a sign over the Reading Room read "Adults Only."

One possible reason that the public education program proved so appealing is that its success was easy to measure (by tracking, for example, how many students benefited from the Society's holdings). There seemed to be pressure, during this time, to provide quantitative measures of the Society's successes. During Vail's tenure, the Society's annual report began to include a statistical appendix that tracked many of the Society's services. It gave a wide variety of specific facts and figures about the Society, including such measures as the number of elementary, intermediate, and high school students who toured the Society, the number of readers who used the library, and the number of volumes requested from library staff. But statistical measures such as these do not fully convey the basic value and importance of a research library. In an attempt to quantify the library's essential output, the Society began to report the number of publications in which the author acknowledged the Society for its assistance. This number, reported annually from 1952 to 1975, averaged 60 publications per year. The year of the fewest acknowledgments was 1956, with 35, and the year with the most was 1975, with 108.

Although these statistical measures helped document the range of services being offered, the self-esteem of the institution continued to depend largely on the size and quality of its holdings. Moreover, members of the board of trustees considered themselves collectors first and saw the role of the Society primarily as a repository of important material. Consequently, great emphasis was placed on acquisitions, and most of each annual report was devoted to descriptions of items purchased by or donated to the Society during the year.

Emphasis on acquisitions was not, in and of itself, a bad thing; quite the contrary. The Society's collections were its chief asset. But an emphasis on acquisitions, particularly to the extent that quantity was regarded as important, could be dangerous. As mentioned earlier, the Society had a long history of accepting anything and everything that was given to it with little regard for the quality of the gift, the institution's capacity to absorb it, or the relevance of the gift to the Society's mission.

Donald Shelley, the art and museum curator during this period, called for a more focused acquisitions policy. As he put it, "The Society continually tried to make accessible to the public . . . accumulations which had nothing to do with American or New York history." Further, he called for "a detailed survey and analysis of our actual holdings" to "reveal the strengths and weaknesses which must henceforth determine the direction of our development." By 1947, Shelley believed that the Society had made some progress: "As the year closes, consideration is being given to the possibility of showing our European paintings elsewhere, thus. . . enabling us to devote ourselves entirely to early American art. Certainly such a solution will help us better to meet present-day competition from sister art institutions specializing in the same or related fields." In 1948, a list of 634 paintings was circulated among various cultural institutions in the city, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[] No museums took the Society up on its offer, however, and in 1949, Shelley's position was eliminated in the course of financial cutbacks. There were no further attempts to loan or donate the pictures for the durati