The Last of the Early Years, 1960-1970

On April 1, 1960, James J. Heslin was named director of the Society, a position he would hold for twenty-two years. His tenure can be divided into two distinct periods: a relatively prosperous period from 1960 to 1969, when investment returns were strong and inflation was relatively modest, and a much more difficult period from 1970 to 1982, when poor performance of the financial markets and limited public and private support constrained revenues at the same time that inflation drove up expenses. In addition to these external factors, the two periods are also identifiable by a change in the leadership of the Society's board of trustees. For most of the 1960s, Frederick B. Adams Jr. was president of the board; succeeding him was Robert G. Goelet.

Like his predecessors, Heslin was a librarian by training. After receiving his Ph.D. in American history from Boston University in 1952, Heslin received a master's degree in library service from Columbia University in 1954. Heslin then served as assistant director of libraries at the University of Buffalo, the position he held when he was hired by the Society to be its librarian in 1956. He was promoted to assistant, then associate director of the Society between 1956 and 1960. Because Heslin had been Vail's deputy, the transition to new leadership was smooth and relatively uneventful. Not surprisingly, the issues that emerged toward the end of Vail's tenure—acquisitions policy and cataloging—dominated Heslin's early years in office.

In his first annual report as director and librarian in 1960, Heslin quoted a Society librarian's report originally published in the Society's Proceedings in 1843: "The Librarian would now urge upon the Society, as the first object of attention, the preparation of a new and methodical catalog of the whole collection. The library, although generally in excellent preservation, and so far as mere arrangements are concerned, conveniently dispersed, is almost inaccessible to general use from the want of one." Bringing the argument up-to-date, Heslin continued: "It is impossible to pursue our acquisitions with any certainty unless we possess the means of regular periodical examination" of the collections, a process "only afforded by a catalog." He dutifully reported progress on the catalog in annual reports from the early 1960s, noting that "the importance of the catalog was second only to the richness of the collections themselves."

In the January 1962 Quarterly, Heslin wrote an article titled "Library Acquisition Policy of The New-York Historical Society." The article reviewed briefly the history of the Society's collections policies and pointed out precedents for narrowing the scope of the collections. As examples, Heslin referred to the Society's extensive collection of natural history specimens, which were donated to the Lyceum of Natural History in 1829, and the Society's collection of Egyptian antiquities, which was sold to the Brooklyn Museum in the 1930s.

The impetus for Heslin's interest in the catalog and acquisitions policy was definitely the Wroth report. Indeed, in his article, Heslin reiterated many of Wroth's recommendations, particularly the need for an acquisitions policy that would establish chronological and geographical limitations on collecting. Like Wroth, Heslin believed that many libraries were now adequately collecting material relating to the present period and to particular localities and that many libraries in the city and state of New York had collections that were strong in material dating from 1850. "The greatest strength of the Society's collections," Wroth wrote (and Heslin reprinted), "rested in rare Americana and retrospective material."

After considering the Wroth report, the Society's board of trustees adopted a new acquisitions policy that identified twenty-one separate categories, assessed the strength of the collections in each category, and issued a guiding statement for future acquisitions. The categories enumerated in the policy cover a broad spectrum, including American fiction, poetry, and belles lettres; the California gold rush; the Civil War; New York City and State; slavery; sheet music and songsters; and professional literature.[]

One reason that Heslin and the board were able to pay such close attention to cataloging and acquisitions was the Society's prosperous financial condition. By 1962, the Society had run its ninth consecutive surplus, and the board-restricted accumulated surplus stood at $217,OOO.[] The 1961 annual report referred to the Society's quiet and steady growth, and the 1962 report pointed out the Society's "healthy financial situation."

It may have come as a surprise to some, then, when Frederick B. Adams, who took over as president in 1963, appealed for help in addressing serious needs the Society faced. In his first annual report, Adams showed courage and foresight in his summary of the Society's financial position. He pointed out that although the value of the Society's endowment had increased significantly since 1948, there had also been a large increase in payroll and benefits for the staff over the same time period, despite the fact that the total payroll had been reduced from seventy-two to sixty-four persons. He warned that a continuation of that trend without additional revenue was not sustainable.

Furthermore, Adams stressed that since the Society was housed in a structure built at the turn of the century, major capital investments were necessary. Not only did the Society need to invest in a general renovation of the building and a re-installation of its galleries, but it also very much needed to install an air-conditioning and ventilation system. Rather than being required merely for staff comfort, an air-conditioning system was essential to protect the Society's collections. Not only would the system provide temperature control, but it would also eliminate open windows that brought the city's damaging soot into the building. Adams estimated that $1 million would be required to complete these projects, an amount that could not be captured through operating surpluses. We have "begun to marshal our forces," he wrote, "to seek special grants and gifts from foundations and individuals"—in other words, to launch a capital campaign.

While the development drive was under way, Adams underscored the Society's need for assistance: "I used to hear it said, by the Society's members as well as by outsiders, that we were a rich institution with never a worry about budgets. I am glad that this is not true; such affluence would make us complacent." He noted that the response to the Society's campaign "had not been overwhelming" but that "the state of the Society is healthy in that we are aware of our shortcomings and are prepared to do something about them."

Adams also showed strong leadership in other ways. In an effort to expand and diversify the Society's sources of revenue, he encouraged the board of trustees to revise its by-laws to provide, "among other things, for new classes of membership, with higher rates of contribution over the regular annual dues of $10." Although such steps did not necessarily bring in significant income, they sent a signal to the Society's supporters that more revenue was needed. In addition, he moved to simplify the administrative structure of the board by reducing the number of committees from eleven to eight by dissolving two committees and merging two others. Adams pointed out that the committees, though there were fewer of them, had become considerably more active. Under Adams's guidance, the Society's board was more active than it had been since the days of George Zabriskie.

The Society began the renovation in 1966, closing most of the galleries and parts of the library for much of the year. Although a substantial sum had been raised during the capital campaign—approximately $574,000 by the end of 1966—the money did not cover all construction expenses. Fortunately, aware of the scale of the project, Adams and the board had anticipated this possibility and had redesignated the accumulated surplus fund as a "reserve for equipment, building replacement, and major repair." Approximately $316,000 of the money used to fund the improvements came from these reserves.

In early 1967, Frank Streeter, the Society's treasurer, reminded the board of the more than $300,000 that had been drawn from reserves to fund the capital renovations. He encouraged the Society to mount a campaign to replace those funds.[] Such a campaign was never initiated. In March 1967, however, the board of trustees did create a new class of supporters called the Pintard Fellows to aid in furthering the purposes of the Society. To become a Pintard Fellow, one had to contribute $100 or more to the Pintard Fund. Specifically, the objectives of the Pintard Fellows were (1) "to promote a better understanding of the Society's purpose and significance, and a closer knowledge of its collections" and (2) "to promote the interests of the Society by contributing funds for its benefit, especially for acquisitions, installations, and publications." Although establishing the Pintard Fellows was a commendable step, the amount of funds raised was quite small ($12,368 in 1967) and hence were used for smaller projects or to purchase particular items for the Society's collections. The Pintard Fund did not, and could not, begin to replace the reserves drawn down during the 1966 renovations.

Instead, with its reserves mostly depleted and struggling to balance revenues and expenditures, the Society's board of trustees took a step to increase the income that could be spent from its endowment: it adopted a "total return" investment policy. Prior to this action, the Society spent only the dividend and interest income generated by its endowment. It did not spend any portion of realized gains generated through capital appreciation of the portfolio. Such a policy encouraged the Society to forgo growth investments (such as small company stocks) for investments that generated the most current return (such as bonds).

The new total return policy allowed the Society to spend up to 5 percent of the endowment's market value annually (based on a three-year moving average of the endowment), irrespective of whether the endowment actually generated that amount of dividends and interest. In the annual report for 1967, Adams, referring to the remarkable growth in the market value of the endowment, explained it this way: "This [1967 investment] performance would not have been possible if the funds had been entirely invested in bonds to secure maximum return. Yet the portion of our money invested in 'growth' stocks produces initially a very low rate of income because of the retention of earnings by rapidly expanding companies. With rising costs of operation, the Society needs to increase income, yet prudent investment for the future in an inflationary economy dictates the purchase of substantial percentages of securities whose present yield is low." Adopting a total return philosophy allowed the Society to pursue a goal of maximizing the growth of its endowment without sacrificing current income.[]

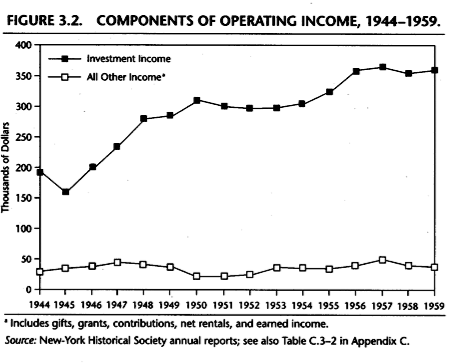

The impact of the new strategy on the Society's operating budget was substantial. In 1967, for example, proceeds from transferred realized gains (to bring spending up to the 5 percent limit) amounted to $244,204, increasing investment income by 48 percent over the 1966 investment income total of $509,000. This increase is represented by the discontinuity, or jump, in the Society's total revenues as depicted in Figure 4.1. It should be pointed out, however, that the newly available realized gains relieved the pressure on Society leadership both to develop new revenue sources and to limit the growth of expenditures. Between 1966 and 1970, total operating expenses increased at a rate of 9.5 percent per year, while revenues were flat, increasing at an average rate of literally 0 percent per year.[] The growth in expenditures coupled with the lack of growth in revenue created a financial vise that would begin to close on the Society as the 1970s neared.

Nevertheless, the tremendous jump in revenue put Society leadership in an expansive mood. A major building renovation had been completed, the galleries were reinstalled and redecorated, and in the library, the lighting was redesigned and a new carpet was installed. With the renovations complete and the increase in spendable investment income, the Society's focus shifted toward becoming a more popular institution, increasing the emphasis given to the museum, education, and special programs.

In 1967, Heslin reported "that the Sunday afternoon concerts were the most successful in the fifteen-year history of these events, and it is obvious that they have become an institution." Heslin also suggested that "the need for more school programs is clearly a pressing one." Late in 1967, the Society received a three-year grant ($26,700 annually) from the New York State Council on the Arts to expand its education program. A four-person education department was established in 1968 and was responsible for the Society's program for schools as well as for overseeing the growing number of films, music recitals, and children's programs offered by the Society. Within eight years, attendance at these programs increased more than 50 percent, from 21,937 in 1964 to 33,063 in 1970. Moreover, general attendance at the Society reached an all-time high of nearly 109,000 in 1968, a year that Society leadership referred to as "one of the best in the Society's long history." At this point, attendance at all Society events was free, and as Adams pointed out, the Society "fulfills an increasingly useful function in the city's educational and cultural life, at no charge to the municipal budget."

As the Society shifted its focus outward toward serving a growing constituency, the emphasis in its collections management shifted as well. The primary focus following the Wroth report had been on cataloging the collections; as the 1960s passed, the emphasis shifted to acquisitions. In the 1967 annual report, Adams wrote: "While we are conscious of the fact that our source material must be catalogued and made available, we are always aware that the first objective is to strengthen our collections." In the Report of the Library in 1969, James Gregory, the librarian, wrote that "the making of thoughtful and knowledgeable additions to the collections of the library is the most permanent and therefore the most important work of 1969, or any other year." Further evidence that cataloging was diminishing in importance is reflected by administrative decisions; between 1966 and 1970, the cataloging staff was reduced from five full-time catalogers to just three. By 1975, the cataloging staff had been reduced to one.

In addition to diverting resources from cataloging, management's renewed emphasis on acquisitions and growth of the collections conflicted with the recommendations of the Wroth report. The report's second major emphasis, narrowing the Society's acquisitions policy both chronologically and geographically, also faded in importance through the 1960s. In 1970, Gregory issued an appeal for contemporary books: "Friends of the Society who have useful—they need not be rare—books are urged to offer them to the Library. A fairly common book in 1970 may be quite scarce by 2070. But the need for these current books is much more immediate. . .. A growing number of young historians are studying the recent past from sources in nearly contemporary publications. It appears that interest in current history will continue." Similarly, the Society continued to acquire, by purchase and gift, items not related to New York or the surrounding region or colonial America, including a collection of lithographs purchased in 1969 depicting the California gold rush. In the acquisitions policy adopted by the trustees in 1959, it had been recommended that primary materials on the California gold rush not be acquired.

As the 1960s drew to a close, so did the presidency of Frederick B. Adams Jr. Under his leadership, the Society completed a successful campaign that helped finance major capital renovations; the Society's board was restructured and the Society's first female trustee was elected; the Society adopted a total return approach to the spending of investment proceeds from endowment; and the Pintard Fellows were established. In addition, the Society's renovated exhibition spaces and expanded emphasis on public programs positioned it to serve a larger constituency than it ever had before.

Not all the news had been good, however; the latter part of Adams's tenure exhibited a shift away from the careful stewardship that characterized his early years. Whereas Adams had shown great caution in 1963, warning the Society of impending budget problems and urging a capital campaign even as the Society was running surpluses, he and the board did not anticipate or respond to the financial difficulties of the late 1960s. There is no mention of financial concern in the remaining reports of the period; in fact, it was not until 1970, after the Society suffered its first operating deficit in many years, that Adams sounded the alarm. That was the first year that the Society's total return investment policy and 5 percent spending rule did not provide sufficient income to cover expenditures. As he turned over the presidency to Robert G. Goelet, Adams warned that "the prospect for 1971 and beyond is not cheerful; we shall have to draw heavily on our carefully husbanded Reserve Fund balance to make up operating deficits."

Formula for Disaster: Dramatic Change Outside, Status Quo Inside, 1971-1982

The 1970s proved to be an extraordinarily difficult decade for all cultural institutions, especially those that depended on endowment for much of their income. The "stagflation" of that period affected these institutions negatively in terms of both revenues and expenses. On the revenue side, the recessionary economy that prevailed during the early 1970s reduced the return on these institutions' investments, driving down total income. In 1973 and 1974, for example, the annual total return for domestic common stocks was -14.8 percent and -26.4 percent, respectively.[] As for expenses, inflationary pressure from the oil crisis, among other things, drove up the cost of operations during the same period.

The Society's ability to meet the challenges was constrained. First, the capital improvements and renovations had reduced the Society's unrestricted reserves, inhibiting its financial flexibility. Second, and equally important, the Society continued to move aggressively to expand its services to a rapidly growing public constituency just as the financial noose was tightening. As had happened at other times in the Society's history, the expansion of services (and the concomitant growth in expenditures) was not matched by a comparable growth in existing revenue or by the identification of new sources of revenue.

On January 27, 1971, Robert G. Goelet was elected president of the N-YHS, thereby earning the unenviable task of leading the Society through this challenging period. Goelet was a direct descendent of Francis Goelet, a Huguenot who had immigrated to North America in 1676. Over the years, the Goelet family rose to the highest levels of real estate, banking, and the arts in New York. In the early 1900s, Goelet's father, Robert Walton Goelet, built on the family's already sizable fortune, amassing real estate parcels that even at Depression era prices were estimated to be worth well over $15 million in 1932.[] At about that time, the Goelet real estate holdings were estimated to be the most valuable owned by any single New York family other than the Astors. Upon graduating from Harvard in 1945, Goelet worked in the family's various business and real estate concerns, eventually serving as chairman of R.I. Corporation and president of Goelet Realty.

Like many of his peers, Goelet took great interest in a variety of cultural and philanthropic institutions. At the time of his election to the Society's board of trustees in 1961, he was on the board of the American Museum of Natural History (of which he later became chairman), the New York Zoological Society, the Phipps Houses, and the National Audubon Society. During his nearly ten years on the N-YHS board, his primary focus was the Society's museum; in fact, he had chaired the board's museum committee for much of his tenure. His election to president marked the first time that the Society's top-ranking board officer had not served on either the library committee or the finance committee.

Under Goelet, the Society continued down the path on which it had embarked in the late 1960s, focusing on improving the galleries, increasing general attendance, broadening the Society's acquisitions and collections management policies, and expanding public programs. In the 1971 annual report, Richard Koke, the director of the museum, expressed the Society's renewed commitment to the museum: "For several years the course for the museum, chosen by the Trustees, has been directed toward strengthening its program and collections to bring it to the high position that it enjoyed in public favor in the 19th century." To help it achieve that lofty goal, the Society hired Mary Black to fill a new position, curator of painting, sculpture, and decorative arts.

For his part, Goelet gave the museum top billing in his first annual report, introducing the report of the president by expressing his satisfaction with the improvements of the museum, noting "the Society's. . . continued progress in the modernization and reinstallation of our museum galleries." Although no one would question the basic desire to improve the museum, returning it to its nineteenth-century stature was simply not possible. The museum had achieved its earlier status without competition from the many museums that had established themselves in New York City in the intervening hundred years, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, located directly across Central Park.

Still, by most standards, the Society's initiatives were successful. In 1972, the Society's museum was awarded a certificate of formal accreditation by the American Association of Museums. More important, the Society's efforts were well received by the public. For the first time ever, the Society exhibited its entire collection of 433 Audubon watercolors, and tens of thousands of visitors came to see the exhibition. The Society also created the Library Gallery to exhibit selected items from the library collections. The popularity of those exhibits exceeded even the Society's expectations. Because of these and other initiatives, general attendance at the Society increased dramatically. Between 1971 and 1973, the Society's attendance figures increased by 172 percent, from 136,324 to 351,727. As the United States prepared to celebrate its Bicentennial, the extraordinary collections of the Society would be much in demand.

The Society's desire to expand was not limited to its programs and services; it extended to its collections management policy as well. As previously mentioned, the Society's accessions in the late 1960s did not conform strictly to the guidelines set forth in the 1959 acquisitions policy enacted following the Wroth report. On April 28, 1971, the board of trustees moved to formalize the broadening of that policy, approving a set of modifications to provide "a broader base" for the maintenance and strengthening of the Society's collections. The modifications significantly expanded the Society's reach. For example, the 1959 policy suggested that "no primary material relating to the California Gold Rush be acquired in the future. It is suggested that secondary material be purchased only selectively." As amended, the new policy stated that "printed primary and secondary material [on the California Gold Rush] will be purchased which relates to the collection we now have."[] Similar changes, relaxing either thematic or geographical restrictions, were made to recommendations for five collections: slavery, military history, biographies, travels in the United States, and political caricatures and posters.

In the years following this change in official policy, the Society's officers and staff also widened the scope of its collecting chronologically. In his 1973 Report of the Library, James Gregory wrote that "as always, the majority of the books added to the library are recent ones that we believe to have lasting research value." To justify this growing emphasis on recent works, in the 1974 annual report Heslin wrote: "History could be as long ago as 1775, or it can be as recent as last week. To collect items of importance relating to both periods is our function." Gregory elaborated further in the same annual report: "We acquire recently published books as well as old ones. New books and current periodicals are vital to the collection, for some contain the findings of recent historical scholarship and others are the firsthand records of our own time and the primary sources for tomorrow's historians. ... A commonplace book today may be a rarity of the future." It is true that there is a need for libraries that will collect these materials; one wonders, however, if the policies are appropriate for an institution of limited resources with a mission and demonstrated strengths firmly planted in the history of America prior to 1900.

The increasing emphasis on acquisitions was reflected in changes in the levels of the board-restricted funds. Year-end balances of these funds, originated under then-president LeRoy Kimball in 1954 to help the board manage the Society's accumulated surpluses, are depicted in Figure 4.2.

Prior to Frederick Adams's tenure as board president, the three board-restricted funds were the accumulated surplus, the pension reserve, and the fund for special accessions. As mentioned previously, Adams had established a development fund and renamed the accumulated surplus (calling it, instead, the reserve for equipment, building replacement, and major repair) as part of the capital campaign to improve the Society's facilities. To pay for the renovation in 1966, the building reserve was totally depleted and the development fund was substantially reduced. After the renovation, Adams rebuilt the development fund with surpluses generated in the late 1960s. When Adams stepped down in 1970, the development fund stood at $302,000.

Under Goelet, the board spent down this reserve quickly, depleting it entirely in just three years. Rather surprisingly, however, the development fund was not spent down to finance deficits. Expenditures were cut in 1971 and 1972, and the Society posted relatively small deficits (approximately 3 percent of total expenditures) in 1971 and 1973.[] Although the financial statements do not explicitly state where the development fund reserves were transferred, it is apparent from Figure 4.2 that the special accessions fund was the beneficiary of a good portion of those transfers. As the development fund fell from $302,000 to zero, the accessions fund rose from $42,000 to $250,000.

Pressure to ensure that funds would be available to make important accessions can be seen in other ways as well. The Society began to entertain the possibility of selling some of its collections, particularly its European paintings. Originally received by the Society in 1867, many of these pictures were amassed by Thomas J. Bryan, one of America’s first serious collectors of European Art. Although some considered the collection important as a unique representation of early American tastes in European art, the Society maintained that the paintings did not fall within its mission. By selling the paintings, some of which were quite valuable, the Society hoped to further its capacity to purchase collections that were relevant to its mission and purposes.[] The proposal was to sell the majority of the paintings and use the proceeds to finance future acquisitions of American paintings. The Society would retain a small varied group of the Bryan paintings to continue to serve as an example of early American collecting tastes.

The Society originally petitioned the Supreme Court of New York for cypres relief in the mid 1960s.[] It was not until May 1970 that the Society received permission from the court to sell 210 pictures. In May 1971, the Society sold at auction 13 paintings for $109,200. The first $80,000 was used to pay legal expenses, and the balance was used to establish the Bryan Fund, which was to be used only for the purchase of paintings. On Dec