Expansion and the Pursuit of a Real Estate Windfall, 1982-1984

On June 10, 1982, a special meeting of the board was held to name James B. Bell director of The New-York Historical Society. A graduate of the University of Minnesota with a doctorate in history from Balliol College at Oxford, Bell had taught at Ohio State and Princeton. Immediately before coming to the Society, he had been the director of the New England Historic Genealogical Society for more than nine years. Introducing Bell in the annual report of 1982, Society President Robert Goelet expressed his enthusiasm for the new director: "Although he has been with us for only a short period, Dr. Bell has already begun to place his mark on the Society. In the report that follows, he details new programs that he and his staff have introduced. Judging from what he has undertaken, the years to come promise to be productive and exciting ones."

Still, Goelet closed the 1982 annual report with these words of caution addressed to the membership: "Your society needs to broaden its membership base and enlarge the number of its corporate and foundation contributors. The level of annual deficits incurred in recent years simply cannot be allowed to continue. We will need your help in implementing what I trust will be a most successful era in the history of your society."

From the very start, Bell's emphasis was on new programs, new initiatives, and the development of a new attitude at the Society. Perhaps in response to the beleaguered and more or less moribund last years of his predecessor, Bell sought to reestablish the Society as an active institution. In his first annual report, Bell wrote of the progress that had been made by the Society in a variety of areas. He pointed to the publication of the New-York Historical Society Gazette, a newsletter to keep members informed of the goings-on at the Society. A comprehensive evaluation was under way of the collecting, lending, and exhibition policies of the museum as well as a plan to renovate the Society's museum storage areas. On the library side, Bell wrote of two grants that brought the Society into the computer age. Awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the grants funded two new programs: one provided resources to enable the Society to enter its holdings in an on-line catalog called the Research Libraries Information Network (RLIN), and the other helped the Society to develop a computerized catalog of its extensive newspaper holdings. In terms of public service, the Society continued its long-running lecture series and began to sponsor conferences for scholars on topics of general interest and significance.

Bell was out to remake the Society, and he was going to do it with gusto. Looking back on his first months in office, Bell wrote: "These are only some of the programs that the Society will provide in the years to come. The challenge that the staff and I have undertaken is to build on the Society's record of 178 years of distinguished service to the city, state, and nation. We accept that challenge with enthusiasm."

Bell moved to take advantage of the positive glow that surrounds new leadership. In an article in the New York Times headed "How a Small Museum Puts on Its Big Shows," Bell called his institution "the best-kept secret in New York." The article pointed out that "few people" visit The New-York Historical Society. "A lot of people don't know what's in it. Some people have never even heard of it.'[] The article then attempted to augment the Society's reputation by discussing its valuable collections and its many different exhibits. In addition to describing how a small museum differs from a large museum, the article also gave Bell an opportunity to discuss his future plans for the N-YHS. He said the Society was going to "take off in new directions," mounting more theme exhibitions and paying more attention to what he termed "neglected collections" such as the extraordinary cache of architectural drawings.

Bell aggressively enlarged and expanded the Society's services and programs, but he did so with little apparent regard for how these initiatives would be financed. Perhaps he and the trustees believed that development of the Society's real estate was the answer to the fiscal predicament. Without sufficient current revenues available to support the new initiatives, the Society continued the policy that had been established in the late 1970s, spending realized gains in excess of the established limit of 5 percent of the market value of the endowment. In fact, the expansion undertaken by Bell required the Society to withdraw more from its endowment than it ever had before. After six months with Bell as director, the Society's total unrestricted operating expenses for the year had increased 11 percent, while operating revenues decreased 4 percent. To pay for this expansion, the Society spent $1.9 million in proceeds from the endowment, a staggering 16.9 percent of the endowment's total value.[]

Society leadership was aware that it had to generate more funds. As 1982 drew to a close, the Society issued its first "annual appeal," a mailing sent out to the membership encouraging end-of-year contributions. It was the first time the membership had been systematically canvassed for funds beyond the standard dues. Response to the appeal was positive but did not have a significant impact on the Society's financial situation. During 1983, and on a nearly monthly basis, the Society's treasurer, Margaret Platten, repeatedly warned her fellow trustees of the growing gap between revenues and expenditures.[] In January 1983, she urged the trustees to consider hiring a professional to help with fundraising. She repeated her plea in trustee meetings in February and March; finally, in April, George Trescher, a fundraising consultant, was retained. In May, Platten reiterated her concern about the budget gap and spoke of the Society's urgent need for revenues. In July, she was critical of the steps being taken, saying that "fund-raising efforts are, at best, modest." As members of the board grew increasingly worried about the financial situation, Bell, too, became concerned: the burgeoning deficit limited his ability to offer the programs he regarded as important. The library had urgent needs, Bell contended. He explained to the trustees that the library "needs space, has personnel problems, and is in need of defining again its collecting and acquisition interests." Bell also reminded the trustees that the recommendations of the 1956 Wroth report had never been pursued. Bell also pointed out that the Society's problems were not limited to the library. He asserted that "the museum department was not properly funded to carry out its work, although more than 98 percent of the visitors to the Society come to see the various exhibitions." Within the Society, responsibility for the budget seemed to remain, at least at this point, a board matter. There is no evidence that Bell was criticized or was even held accountable for the growing budget deficit. Bell's monthly reports to the board consisted of discussions of the progress of programs, not the progress toward financial stability.

Bell's administrative honeymoon was brief. Less than six months after he took office, public controversy developed around his dismissal of Mary Black, the Society's curator of painting and sculpture. Black, who had been at the Society since 1970 and was sixty years old, was dismissed on December 29, 1982, without, she said, "prior notice or explanation." She also said that Bell refused to give her a letter outlining the reasons for her dismissal. She filed a complaint against the Society in early 1983 claiming that the Society had violated sex and age discrimination laws.[]

In February, the Society's board of trustees formed a special committee to deal with the matter. Shortly thereafter, sixteen prominent New Yorkers sent a letter to the Society protesting Black's termination and released it to die press. The letter, parts of which were excerpted in an article in the New York Times, asserted that "Mary Black had been fired—dismissed with no explanation, on short notice, with meager allowance for financial hardship, and given three hours for the removal of personal belongings with the threat of eviction for trespass after that." It added that the dismissal was "very difficult for anyone acquainted with Mary Black's age, career and accomplishments to comprehend."[] Both Bell and Goelet declined to comment, citing Black's civil complaint. Trustee discussions on this issue continued for more than a year, until in April 1984, the Society and Black reached a settlement.

Although it is not uncommon for a new leader to struggle through difficult personnel issues during a transition period, the negative publicity helped neither Bell nor the Society. For example, among the signers of the letter of protest was Kent L. Barwick, chairman of New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission. The leader of that agency was not a person the Society wanted to offend as it was quietly preparing plans to develop a residential tower adjacent to and over its landmark building.

Another controversy developed, this time within the Society's walls, around Bell's pledge to "pay more attention" to the Society's architectural drawings. The new emphasis created tensions between Society staff and the board. Although a survey of the drawings was completed quickly and presented to the trustees on January 26, 1983, changing the way drawings were used proved to be more difficult. Battle lines were drawn within the Society over whether the drawings, along with other prints and photographs, ought to reside under the jurisdiction of the museum or the library. Apparently, Bell's idea to do more with these neglected collections involved moving them from the library into the museum, a move proposed in a museum committee report issued in February 1983. In that report, the committee criticized the underutilization of the prints and indicated that the Society should be more aggressive in pursuing twentieth-century items. It presented a "wish list" of print makers and photographers whose works the Society ought to pursue.

Larry Sullivan, the librarian, was vehemently opposed to shifting responsibility for the prints, photos, and drawings to the museum. In April 1983, he presented to the trustees a document titled "Report on the Print Room as a Library Division." The report attacked the proposal from the museum committee and outlined the many and varied reasons for his opposition.

Sullivan wrote that "the Print Room is most heavily used as a research facility and its traditional designation as a Library division acknowledges its primary role as a visual and architectural archive." Sullivan also emphasized that the collections of the Print Room had been built with knowledge of the holdings of its sister institutions. Sullivan pointed out that the museum committee report ignored the collections of other institutions in assembling its wish list, including artists whose works were already well represented at institutions like the New York Public Library and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Furthermore, although Sullivan did not directly question the appropriateness of pursuing twentieth-century work given the Society's mission and strengths, he did write that "pursuit of 20th century prints and photographs should not detract from a longstanding commitment to the N-YHS's strength in 18th and 19th century material." In addition, Sullivan argued that applying the more detailed museum accessioning and cataloging processes to the 10,000 prints, 500,000 photographs, 140,000 architectural drawings, and over a million Landauer items would be impossible. Conversely, the Society's library cataloging procedures and participation in RLIN would make it possible for the collections to become accessible through library database networks. Finally, Sullivan pointed out that a recent exhibition from the Landauer collection illustrated the proper relationship between the library and the museum. The museum staff selected the material and designed the show, while the library staff kept the collection open to researchers, assisted in locating items for the exhibit, and provided background information as needed. In essence, important functions were fulfilled without interrupting normal service to scholars. Sullivan implied that no such interaction would be possible if the prints, photos, and drawings were exclusively under the aegis of the museum.

To emphasize further his opposition to the proposal, Sullivan quoted extensively from a memo written by Richard Koke, the museum director, which showed that he, too, opposed the transfer. Koke wrote that he considered the suggestion to move the print collections out of the library "pointless and reflecting very little knowledge of the function of the Print Department and its relation to the Society. . . . The fact that the museum, at times, draws upon the print collections for exhibitions provides no valid reason to transfer custody of this material. . . . The collection serves as a valuable adjunct (apart from preservation) for the use of scholars, researchers, and the public, which has nothing to do with exhibits." Koke concluded by saying that "the print department is not, as the [proposal] would intimate, a 'grab bag' for the benefit of the museum, and I certainly fail to see anything in the suggestion that it be transferred to the museum. It certainly is [in] nobody's interest to do this."

When Sullivan's report was presented to the board, it provoked spirited discussion. Goelet noted that "the issue in question is one of longstanding interest to the board of trustees as it has been raised on many previous occasions but never addressed in a serious and systematic manner." Goelet urged a joint meeting of the museum and library committees to resolve the matter. After analysis, no action was taken. The prints, photos, and architectural drawings remained under the management of the librarian, but the definition of the collections remains to this day a matter of continuing debate at the Society.

Less than two weeks after the New York Times article on Mary Black's dismissal was published, Society officials and the developer Robert Quinlan appeared before one hundred neighborhood residents to discuss the possibilities for real estate development on the site. The reaction from West Side residents was hostile. Although no formal plans were presented, Quinlan said the Society could add 292,000 square feet of space in a twenty-story structure and remain within existing zoning limitations. When asked why such a development was necessary, Goelet said, "Frankly, [the Society] is badly in need of income." He then referred to the Society's annual operating losses of between $500,000 and $700,000 and added that "you can't keep that up indefinitely. The trustees decided that the one asset they had that was nonproducing was the land . . . and the development rights that ran with it. It seemed to us that this could provide an important source of capital and would also possibly solve our space problems."[]

Neighborhood residents were not convinced by the argument. After Goelet said that most of the Society's operating expenses were paid for by endowment income, many in the audience questioned the seriousness of the Society's other fundraising efforts. Goelet's long-standing inability to articulate clearly the acute nature of the Society's financial situation was coming back to haunt him. The Society was unable to engender any sympathy for its economic difficulties. Most people felt that the Society wanted to develop its real estate to enlarge its galleries and offices and to expand its programs.

The plans for the twenty-one-story peak-roofed tower were presented to the Landmarks Preservation Commission in early 1984, and the response was overwhelmingly negative. The animosity was not directed at the design of the tower so much as at the precedent it would set and the institution seeking to set it. George Lewis, executive director of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, said, "Surely most people will agree that the architect's design has many strong attractions. Would that apartment houses all over town were done half so well. . . . [But] to certify this proposal as appropriate would open the doors for developers to begin imagining the possibilities in major alterations of landmarks all over town." Councilwoman Ruth Messinger said, "For the Society to seek this luxury residential structure violates its stated commitment to history and preservation and would allow it to engage in speculative real-estate development."[] The Landmarks Preservation Commission rejected the Society's application.

The possibility that real estate development would solve the Society's financial problems was dead, even though Goelet attempted to work with Quinlan and others to revive it. After three years, the agreement with Quinlan was allowed to expire and Quinlan gave the Society his plans and architectural drawings in lieu of the payments that had been scheduled into the contract.

Growing Deficits and a Preoccupation with Consultants and Self-Study, 1984-1986

With the prospects for a windfall from real estate development gone, the Society was forced to reexamine its revenue opportunities. It had no contingency plan. After a nine-month study, George Trescher, the Society's fundraising consultant, presented his findings to the board in January 1984. Trescher's report identified several initiatives that he thought the Society ought to pursue:

Direct mail. The Society must continue to send out mass appeals in an effort to increase its membership.

Fundraising benefits. The Society should consider sponsoring a major fundraising benefit.

Board leadership. The Society must have leadership from the board in terms of donations. It was also suggested that a development committee be established.

Corporate membership. The Society should aggressively pursue corporate membership and sponsorship opportunities.

In response to Trescher's recommendations, the Society initiated plans for a celebration to be held in October in honor of its 180th birthday. In addition, more aggressive efforts were undertaken to have Bell work with key members of the board of trustees to encourage friends and associates to contribute funds, especially from corporations. Finally, the board changed its committee structure. A new committee on development was established, as was a committee on planning and policy. Together, these committees were to address all aspects of the Society's difficult financial circumstances, including "the possibility of disposing of a portion of the library's or museum's collections or to explore finding a new home for the entire collection." Because of the seriousness of the task these committees faced and the extra effort that they would require, Goelet recommended that the museum committee and the library committee be abolished, and they were.

The adverse publicity surrounding the failed real estate proposal, combined with the Society's gloomy financial prospects, seemed to create discord among members of the board. During deliberations on negotiations with developers, there is evidence that the Society's trustees were not kept fully informed on all matters. After Hugh Hardy, the architect of the proposed residential tower, presented detailed and finished plans to the board, Harmon Goldstone noted that it was "the first time he had heard in a systematic manner the details of the proposed project." He added that he had many questions about the project but that the board should proceed with the various administrative steps required for the building. Margaret Platten also voiced reservations, noting for the record that "financial details regarding the project have not been discussed and those matters must be explored carefully."

Board dissension was reflected in other ways as well. Rather surprisingly, given the bad financial situation, the vote on whether to stage the fundraising benefit was not unanimous. Of the fourteen members present, the vote was eleven for, two against, and one abstention. Perhaps the most telling example of board dissension was the fact that just one month after abolishing the library and museum committees, the board overrode its previous action (which had been taken at Goelet's urging) and reestablished them both.

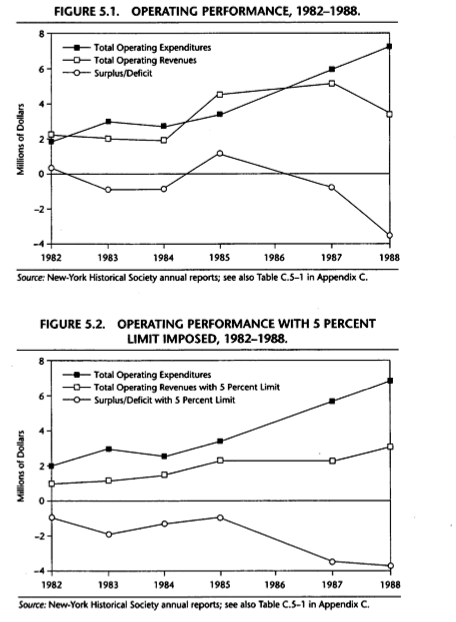

The financial picture also remained bleak. Year-end figures for 1983, Bell's first full year as director, painted a distressing picture. During the year, the Society's total unrestricted operating expenditures grew 53 percent, from $1.9 million to $2.9 million, while revenues grew only 15 percent, from $806,000 to $929,000, thereby creating a 1983 deficit of approximately $2 million—a staggering 66 percent of total expenditures (see Figures 5.1 and 5.2 for a depiction of the Society's operating results).[] To finance the deficit, the Society withdrew $1.7 million from the endowment, 14.3 percent of its three-year average market value.[]

Platten, the treasurer, who had been warning her fellow trustees about the deficit continuously since she assumed the position in late 1982, continued to do so and suggested that the Society consider pursuing additional revenues by investing an increased portion of the endowment in high-yielding fixed-income securities. Conditions did not improve appreciably, and by November 1984, the Society was running a monthly deficit of approximately $ 100,000. Goelet urged trustees to take the matter into their own hands. He proposed that the board raise $200,000 in the last two months of the year so that the annual deficit would at least not grow further. He then pledged $100,000 toward that goal and challenged the rest of the board to meet it. Goelet's gift and appeal to the board helped address the current year's situation but had no impact on the fundamental structural imbalance in the Society's activities. Despite Goelet's efforts, the Society's operating deficit in 1984 was $1.3 million, 48 percent of its total operating budget.

Even as the budget situation worsened, the Society continued to work to expand its services and public outreach efforts. At a meeting of the board in November 1984, the director of public programs for the Society reported on steps "to establish a viable and vigorous public program for the Society." She commented on the recruitment, training, and work of the volunteers program; the lectures, film, and concert programs that had been initiated; and the recently launched programs for school groups. An article in the New York Times promoting the Society's 180th birthday celebration appeared to confirm the success of these initiatives. The article noted that the Society recently had begun "to change its character, from a semiprivate preserve for the wealthy into an institution that welcomes the masses. The museum is open every day but Monday, with special tours available for school groups and a determined effort to draw in the public."[] But as has been noted, such efforts were costly.

At this moment of great crisis, what the Society needed most was strong and focused leadership from its board. The resources available to fulfill the Society's mission were declining, and the Society simply could not afford to be all things to all people. Difficult resource allocation decisions would have to be made. Making those decisions, and developing a realistic plan for implementing them, would require the determination and hard work of a board working together.

Unfortunately, just when the Society needed board leadership the most, circumstances made getting that leadership less likely. Instead of action, members of the board focused on trying to determine exactly how bad the situation was and on how the Society had gotten into difficulty. A significant portion of board activity for the duration of Goelet's tenure was directed toward hiring consultants and hearing their reports, adjusting the board committee structure, and changing the Society's by-laws.

Before taking action to tackle the problems at hand, the board turned to consultants. The work of George Trescher has already been discussed. In April 1985, the executive committee hired Charles Webb to prepare a report on fundraising. His report sought to establish specific areas of responsibility in fundraising for individuals on the board. For example, one board member was assigned responsibility for foundation gifts, another was put in charge of corporate gifts, and a third oversaw social events and benefits.

Shortly after implementing Webb's recommendations, Bell retained the firm of Marts & Lundy to undertake a long-range planning study for the Society with an eye toward a capital campaign. Unfortunately, the study took a year to complete. At the April 1986 meeting of the board, Marts & Lundy presented a comprehensive report that identified ten areas of concern for the Society. The study urged the Society to fill key staff positions, develop policies on collections management, survey and conserve the collections, establish a budget and a schedule for reducing the cataloging backlog, improve the physical facilities, and establish exhibition priorities. These were just the initiatives that required immediate and urgent attention. The report concluded that The New-York Historical Society was not well known and recommended that it consider a capital campaign in the $3 million to $5 million range. The report also identified a series of steps that would have to be taken before launching the campaign: the budget would have to be balanced, experienced fundraisers would have to be recruited, a case statement would have to be prepared, and a nucleus fund would have to be solicited. It was unclear how an organization with the Society's deficit history could have even begun to address the recommendations of the report.

Not long after hiring Marts & Lundy, the board heard a report from a consulting group from Arthur Andersen & Co., who conducted an investigation of the Society's business operations. Their charge was "to identify the administrative functions carried out by the various departments. . . and [determine] the effectiveness of the organization." The report's primary recommendation was that the Society appoint a business manager to oversee financial operations. It also recommended that the Society adopt a new organization structure and hire a deputy director. The board ultimately chose not to change the structure or establish the deputy director position, but it did hire an associate director for administration and a comptroller. The Marts & Lundy study also determined, through interviews with staff members, that the Society did little long-range planning or annual goal setting, had a serious cataloging backlog in both the museum and the library, and was not maximizing its potential to generate income from its museum store, rental of its facilities for events, and sales of photographic reproductions. It is likely that the board was already aware of these shortcomings. Clearly, the list of problems was growing at the very time that the financial resources to deal with them were dwindling.

While the consultants were doing their work, the trustees took steps to resolve organizational problems by revising the board committee structure. First, on Goelet's urging, the board established an executive committee, which was to concern itself with all aspects of the Society's operations. But the committee neither covered new ground nor focused on the top-priority issues. At the February 1985 trustees meeting, the executive committee reported that the Society needed "to strengthen [its] financial resources." The committee also recommended that the Society further expand its public programs, reestablish its publications program, and revive the New-York Historical Society Quarterly. It also spearheaded a new public program that was to provide a summer workshop for New York high school history teachers. To pay for this expansion, the committee urged the Society to retain professional counsel to help it pursue a multifaceted fundraising program that would include "not only the Society's present annual appeal campaign, membership recruitment efforts and proposals for various projects to corporations and foundations, but also a capital fund drive and a benefit program." In a response that was typical of this period, the board deliberated over the recommendations of the executive committee but could not reach a consensus, and "it was agreed to refer the matter again to the executive committee for further consideration."

The board was becoming ever more preoccupied with its own structure. A new committee on publications was established, as was a committee on by-laws and organization. In addition to the executive, publications, and by-laws committees, there were also committees on membership and development, on education, an