of the camp: it is pretending to rough it. It is not roughing it to eat tinned food out of the tin

when a plate costs a penny or two: it is either hypocrisy or slovenliness.

To rough it is to lead an exposed life under conditions which preclude the possibility of

indulging in certain comforts which, in their place and at the right time, are enjoyed and

appreciated. A man may wel be said to rough it when he camps in the open, and dispenses

with the luxuries of civilisation; when he pours a jug of water over himself instead of lying in

ecstasy in an enameled bath; eats a meal of two undefined courses instead of one of five or

six; twangs a banjo to the moon instead of ravishing his ear with a sonata upon the grand

piano; rols himself in a blanket instead of sitting over the library fire; turns in at 9 P.M. and

rises ere the sun has topped the hils instead of keeping late hours and lying abed; sleeps on

the ground or upon a narrow camp-bed (which occasionaly colapses) instead of sprawling at

his ease in a four-poster.

A life of this kind cannot fail to be of benefit to the health; and, after al, the work of a healthy

man is likely to be of greater value than that of one who is anæmic or out of condition. It is the

first duty of a scholar to give attention to his muscles, for he, more than other men, has the

opportunity to become enfeebled by indoor work. Few students can give sufficient time to

physical exercise; but in Egypt the exercise is taken during the course of the work, and not an [287]

hour is wasted. The muscles harden and the health is ensured without the expending of a

moment's thought upon the subject.

Archæology is too often considered to be the pursuit of weak-chested youths and eccentric

old men: it is seldom regarded as a possible vocation for normal persons of sound health and

balanced mind. An athletic and robust young man, clothed in the ordinary costume of a

gentleman, wil tel a new acquaintance that he is an Egyptologist, whereupon the latter wil

exclaim in surprise: "Not realy?—you don't look like one." A kind of mystery surrounds the

science. The layman supposes the antiquarian to be a very profound and erudite person, who

has pored over his books since a baby, and has shunned those games and sports which

generaly make for a healthy constitution. The study of Egyptology is thought to require a

depth of knowledge that places its students outside the limits of normal learning, and

presupposes in them an unhealthy amount of schooling. This, of course, is absurd.

Nobody would expect an engineer who built bridges and dams, or a great military

commander, to be a seedy individual with longish hair, pale face, and weak eyesight; and yet

probably he has twice the brain capacity of the average archæologist. It is because the life of

the antiquarian is, or is generaly thought to be, unhealthy and sluggish that he is so universaly

regarded as a worm.

Some attempt should be made to rid the science of this forbidding aspect; and for this end [288]

students ought to do their best to make it possible for them to be regarded as ordinary,

normal, healthy men. Let them discourage the popular belief that they are prodigies, freaks of

mental expansion. Let their first desire be to show themselves good, useful, hardy, serviceable

citizens or subjects, and they wil do much to remove the stigma from their profession. Let

them be acquainted with the feeling of a bat or racket in the hands, or a saddle between the

knees; let them know the rough path over the mountains, or the diving-pool amongst the

rocks, and their mentality wil not be found to suffer. A winter's "roughing it" in the Theban

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

144/160

necropolis or elsewhere would do much to banish the desire for perpetual residence at home

in the west; and a season in Egypt would alter the point of view of the student more

considerably than he could imagine. Moreover, the appearance of the scholar prancing about

upon his fiery steed (even though it be but an Egyptian donkey) wil help to dispel the current

belief that he is incapable of physical exertion; and his reddened face rising, like the morning

sun, above the rocks on some steep pathway over the Theban hils wil give the passer-by

cause to alter his opinion of those who profess and cal themselves Egyptologists.

As a second argument a subject must be introduced which wil be distasteful to a large

number of archæologists. I refer to the narrow-minded policy of the curators of certain [289]

European and American museums, whose desire it is at al costs to place Egyptian and other

eastern antiquities actualy before the eyes of western students, in order that they and the

public may have the entertainment of examining at home the wonders of lands which they

make no effort to visit. I have no hesitation in saying that the craze for recklessly bringing

away unique antiquities from Egypt to be exhibited in western museums for the satisfaction of

the untraveled man, is the most pernicious bit of foly to be found in the whole broad realm of

archæological misbehaviour.

A museum has three main justifications for its existence. In the first place, like a home for lost

dogs, it is a repository for stray objects. No curator should endeavour to procure for his

museum any antiquity which could be safely exhibited on its original site and in its original

position. He should receive only those stray objects which otherwise would be lost to sight, or

those which would be in danger of destruction. The curator of a picture galery is perfectly

justified in purchasing any old master which is legitimately on sale; but he is not justified in

obtaining a painting direct from the wals of a church where it has hung for centuries, and

where it should stil hang. In the same way a curator of a museum of antiquities should make it

his first endeavour not so much to obtain objects direct from Egypt as to gather in those

antiquities which are in the possession of private persons who cannot be expected to look [290]

after them with due care.

In the second place, a museum is a store-house for historical documents such as papyri and

ostraca, and in this respect it is simply to be regarded as a kind of public library, capable of

unlimited and perfectly legitimate expansion. Such objects are not often found by robbers in

the tombs which they have violated, nor are they snatched from temples to which they belong.

They are almost always found accidentaly, and in a manner which precludes any possibility of

their actual position having much significance. The immediate purchase, for example, by

museum agents of the Tel el Amarna tablets—the correspondence of a great Pharaoh—

which had been discovered by accident, and would perhaps have been destroyed, was most

wise.

In the third place, a museum is a permanent exhibition for the instruction of the public, and for

the enlightenment of students desirous of obtaining comparative knowledge in any one branch

of their work, and for this purpose it should be wel supplied not so much with original

antiquities as with casts, facsimiles, models, and reproductions of al sorts.

To be a serviceable exhibition both for the student and the public a museum does not need to

possess only original antiquities. On the contrary, as a repository for stray objects, a museum

is not to be expected to have a complete series of original antiquities in any class, nor is it the [291]

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

145/160

business of the curator to attempt to fil up the gaps by purchase, except in special cases. To

do so is to encourage the straying of other objects. The curator so often labours under the

delusion that it is his first business to colect together as large a number as possible of valuable

masterpieces. In reality that is a very secondary matter. His first business, if he is an

Egyptologist, is to see that Egyptian masterpieces remain in Egypt so far as is practicable; and

his next is to save what has irrevocably strayed from straying further. If the result of this policy

is a poor colection, then he must devote so much the more time and money to obtaining

facsimiles and reproductions. The keeper of a home for lost dogs does not search the city for

a colie with red spots to complete his series of colies, or for a peculiarly elongated

dachshund to head his procession of those animals. The fewer dogs he has got the better he is

pleased, since this is an indication that a larger number are in safe keeping in their homes. The

home of Egyptian antiquities is Egypt, a fact which wil become more and more realised as

traveling is facilitated.

But the curator generaly has the insatiable appetite of the colector. The authorities of one

museum bid vigorously against those of another at the auction which constantly goes on in the

shops of the dealers in antiquities. They pay huge prices for original statues, vases, or

sarcophagi: prices which would procure for them the finest series of casts or facsimiles, or [292]

would give them valuable additions to their legitimate colection of papyri. And what is it al

for? It is not for the benefit of the general public, who could not tel the difference between a

genuine antiquity and a forgery or reproduction, and who would be perfectly satisfied with the

ordinary, miscelaneous colection of minor antiquities. It is not for that class of Egyptologist

which endeavours to study Egyptian antiquities in Egypt. It is almost solely for the benefit of

the student and scholar who cannot, or wil not, go to Egypt. Soon it comes to be the

curator's pride to observe that savants are hastening to his museum to make their studies. His

civic conceit is tickled by the spectacle of Egyptologists traveling long distances to take notes

in his metropolitan museum. He delights to be able to say that the student can study

Egyptology in his wel-ordered galeries as easily as he can in Egypt itself.

Al this is as wrong-headed as it can be. While he is filing his museum he does not seem to

understand that he is denuding every necropolis in Egypt. I wil give one or two instances of

the destruction wrought by western museums. I them at random from my memory.

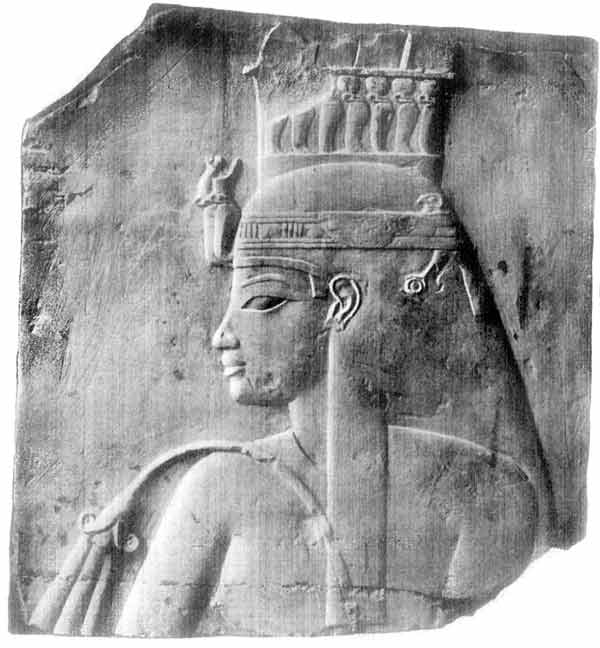

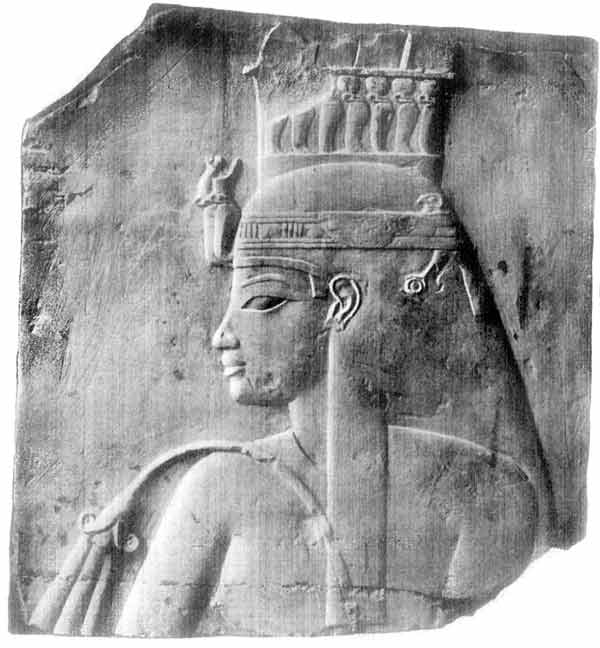

In the year 1900 the then Inspector-General of Antiquities in Upper Egypt discovered a tomb

at Thebes in which there was a beautiful relief sculptured on one of the wals, representing

Queen Tiy. This he photographed (Plate XXVI.), and the tomb was once more buried. In [293]

1908 I chanced upon this monument, and proposed to open it up as a "show place" for

visitors; but alas!—the relief of the queen had disappeared, and only a gaping hole in the wal

remained. It appears that robbers had entered the tomb at about the time of the change of

inspectors; and, realising that this relief would make a valuable exhibit for some western

museum, they had cut out of the wal as much as they could conveniently carry away—

namely, the head and upper part of the figure of Tiy. The hieroglyphic inscription which was

sculptured near the head was carefuly erased, in case it should contain some reference to the

name of the tomb from which they were taking the fragment; and over the face some false

inscriptions were scribbled in Greek characters, so as to give the stone an unrecognisable

appearance. In this condition it was conveyed to a dealer's shop, and it now forms one of the

exhibits in the Royal Museum at Brussels. The photograph on Plate XXVII. shows the

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

146/160

fragment as it appears after being cleaned.

[Photo by T. Capart.

A Relief representing Queen Tiy, from the tomb of Userhat, Thebes.—BRUSSELS MUSEUM.

See Pl. xxvi.

PL. XXVII.

In the same museum, and in others also, there are fragments of beautiful sculpture hacked out

of the wals of the famous tomb of Khaemhat at Thebes. In the British Museum there are large

pieces of wal-paintings broken out of Theban tombs. The famous inscription in the tomb of

Anena at Thebes, which was one of the most important texts of the early XVIIIth Dynasty, [294]

was smashed to pieces several years ago to be sold in smal sections to museums; and the

scholar to whom this volume is dedicated was instrumental in purchasing back for us eleven of

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

147/160

the fragments, which have now been replaced in the tomb, and, with certain fragments in

Europe, form the sole remnant of the once imposing stela. One of the most important scenes

out of the famous reliefs of the Expedition to Pount, at Dêr el Bahri, found its way into the

hands of the dealers, and was ultimately purchased by our museum in Cairo. The beautiful and

important reliefs which decorated the tomb of Horemheb at Sakkâra, hacked out of the wals

by robbers, are now exhibited in six different museums: London, Leyden, Vienna, Bologna,

Alexandria, and Cairo. Of the two hundred tombs of the nobles now to be seen at Thebes, I

cannot, at the moment, recal a single one which has not suffered in this manner at some time

previous to the organisation of the present strict supervision.

The curators of western museums wil argue that had they not purchased these fragments they

would have falen into the hands of less desirable owners. This is quite true, and, indeed, it

forms the nearest approach to justification that can be discovered. Nevertheless, it has to be

remembered that this purchasing of antiquities is the best stimulus to the robber, who is wel

aware that a market is always to be found for his stolen goods. It may seem difficult to [295]

censure the purchaser, for certainly the fragments were "stray" when the bargain was struck,

and it is the business of the curator to colect stray antiquities. But why were they stray? Why

were they ever cut from the wals of the Egyptian monuments? Assuredly because the robbers

knew that museums would purchase them. If there had been no demand there would have

been no supply.

To ask the curators to change their policy, and to purchase only those objects which are

legitimately on sale, would, of course, be as futile as to ask the nations to disarm. The rivalry

between museum and museum would alone prevent a cessation of this indiscriminate traffic. I

can see only one way in which a more sane and moral attitude can be introduced, and that is

by the development of the habit of visiting Egypt and of working upon archæological subjects

in the shadow of the actual monuments. Only the person who is familiar with Egypt can know

the cost of supplying the stay-at-home scholar with exhibits for his museums. Only one who

has resided in Egypt can understand the fact that Egypt itself is the true museum for Egyptian

antiquities. He alone can appreciate the work of the Egyptian Government in preserving the

remains of ancient days.

The resident in Egypt, interested in archæology, comes to look with a kind of horror upon

museums, and to feel extraordinary hostility to what may be caled the museum spirit. He sees [296]

with his own eyes the half-destroyed tombs, which to the museum curator are things far off

and not visualised. While the curator is blandly saying to his visitor: "See, I wil now show you

a beautiful fragment of sculpture from a distant and little-known Theban tomb," the white

resident in Egypt, with black murder in his heart, is saying: "See, I wil show you a beautiful

tomb of which the best part of one wal is utterly destroyed that a fragment might be hacked

out for a distant and little-known European museum."

To a resident in Europe, Egypt seems to be a strange and barbaric land, far, far away beyond

the hils and seas; and her monuments are thought to be at the mercy of wild Bedwin Arabs.

In the less recent travel books there is not a published drawing of a temple in the Nile valey

but has its complement of Arab figures grouped in picturesque attitudes. Here a fire is being lit

at the base of a column, and the black smoke curls upwards to destroy the paintings thereon;

here a group of children sport upon the lap of a colossal statue; and here an Arab tethers his

camel at the steps of the high altar. It is felt, thus, that the objects exhibited in European

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

148/160

museums have been rescued from Egypt and recovered from a distant land. This is not so.

They have been snatched from Egypt and lost to the country of their origin.

He who is wel acquainted with Egypt knows that hundreds of watchmen, and a smal army of [297]

inspectors, engineers, draughtsmen, surveyors, and other officials now guard these

monuments, that strong iron gates bar the doorways against unauthorised visitors, that hourly

patrols pass from monument to monument, and that any damage done is punished by long

terms of imprisonment; he knows that the Egyptian Government spends hundreds of

thousands of pounds upon safeguarding the ancient remains; he is aware that the organisation

of the Department of Antiquities is an extremely important branch of the Ministry of Public

Works. He has seen the temples swept and garnished, the tombs lit with electric light, and the

sanctuaries carefuly rebuilt. He has spun out to the Pyramids in the electric tram or in a taxi-

cab; has stroled in evening dress and opera hat through the hals of Karnak, after dinner at the

hotel; and has rung up the Theban Necropolis on the telephone.

A few seasons' residence in Egypt shifts the point of view in a startling manner. No longer is

the country either distant or insecure; and, realising this, the student becomes more balanced,

and he sees both sides of the question with equal clearness. The archæologist may complain

that it is too expensive a matter to come to Egypt. But why, then, are not the expenses of such

a journey met by the various museums? A hundred pounds wil pay for a student's winter in

Egypt and his journey to and from that country. Such a sum is given readily enough for the [298]

purchase of an antiquity; but surely rightly-minded students are a better investment than

wrongly-acquired antiquities.

It must now be pointed out, as a third argument, that an Egyptologist cannot study his subject

properly unless he be thoroughly familiar with Egypt and the modern Egyptians.

A student who is accustomed to sit at home, working in his library or museum, and who has

never resided in Egypt, or has but traveled for a short time in that country, may do extremely

useful work in one way and another, but that work wil not be faultless. It wil be, as it were,

lop-sided; it wil be coloured with hues of the west, unknown to the land of the Pharaohs and

antithetical thereto. A London architect may design an apparently charming vila for a client in

Jerusalem, but unless he knows by actual and prolonged experience the exigencies of the

climate of Palestine, he wil be liable to make a sad mess of his job. By bitter experience the

military commanders learnt in South Africa that a plan of campaign prepared in England was

of little use to them. The cricketer may play a very good game upon the home ground, but

upon a foreign pitch the first straight bal wil send his bails flying into the clear blue sky.

An archæologist who attempts to record the material relating to the manners and customs of

the ancient Egyptians cannot complete his task, or even assure himself of the accuracy of his [299]

statements, unless he has studied the modern customs and has made himself acquainted with

the permanent conditions of the country. The modern Egyptians, as has been pointed out in

chapter i. (page 28), are the same people as those who bowed the knee to Pharaoh, and

many of their customs stil survive. A student can no more hope to understand the story of

Pharaonic times without an acquaintance with Egypt as she now is than a modern statesman

can hope to understand his own times solely from a study of the past.

Nothing is more paralysing to a student of archæology than continuous book-work. A

colection of hard facts is an extremely beneficial mental exercise, but the deductions drawn

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

149/160

from such a colection should be regarded as an integral part of the work. The road-maker

must also walk upon his road to the land whither it leads him; the shipbuilder must ride the

seas in his vessel, though they be uncharted and unfathomed. Too often the professor wil set

his students to a compilation which leads them no farther than the final fair copy. They wil be

asked to make for him, with infinite labour, a list of the High Priests of Amon; but unless he

has encouraged them to put such life into those figures that each one seems to step from the

page to confront his recorder, unless the name of each cals to mind the very scenes amidst

which he worshipped, then is the work uninspired and as deadening to the student as it is

useful to the professor. A catalogue of ancient scarabs is required, let us suppose, and [300]

students are set to work upon it. They examine hundreds of specimens, they record the

variations in design, they note the differences in the glaze or material. But can they picture the

man who wore the scarab?—can they reconstruct in their minds the scene in the workshop

wherein the scarab was made?—can they hear the song of the workmen or their laughter

when the overseer was not nigh? In a word, does the scarab mean history to them, the history

of a period, of a dynasty, of a craft? Assuredly not, unless the students know Egypt and the

Egyptians, have heard their songs and their laughter, have watched their modern arts and

crafts. Only then are they in a position to reconstruct the picture.

Theodore Roosevelt, in his Romanes lecture at Oxford, gave it as his opinion that the

industrious colector of facts occupied an honourable but not an exalted position; and he

added that the merely scientific historian must rest content with the honour, substantial, but not

of the highest type, that belongs to him who gathers material which some time some master

shal arise to use. Now every student should aim to be a master, to use the material which he

has so laboriously colected; and though at the beginning of his career, and indeed throughout

his life, the gathering of material is a most important part of his work, he should never compile [301]

solely for the sake of compilation, unless he be content to serve simply as a clerk of

archæology.

An archæologist must be an historian. He must conjure up the past; he must play the Witch of

Endor. His lists and indices, his catalogues and note-books, must be but the spels which he

uses to invoke the dead. The spels have no potency until they are pronounced: the lists of the

kings of Egypt have no more than an accidental value until they cal before the curtain of the

mind those monarchs themselves. It is the business of the archæologist to awake the dreaming

dead: not to send the living to sleep. It is his business to make the stones tel their tale: not to

petrify the listener. It is his business to put motion and commotion into the past that the present

may see and hear: not to pin it down, spatchcocked, like a dead thing. In a word, the

archæologist must be in command of that faculty which is known as the historic imagination,

without which Dean Stanley was of opinion that the story of the past could not be told.

But how can that imagination be at once exerted and controled, as it must needs be, unless

the archæologist is so wel acquainted with the conditions of the country about which he writes

that his pictures of it can be said to be accurate? The student must alow himself to be

saturated by the very waters of the Nile before he can permit himself to write of Egypt. He [302]

must know the modern Egyptians before he can construct his model of Pharaoh and his court.

In a recent London play dealing with ancient Egypt, the actor-manager exerted his historic

imagination, in one scene, in so far as to introduce a shadoof or water-hoist, which was

worked as a naturalistic side-action to the main incident. But, unfortunately, it was displayed

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

150/160

upon a hilside where no water could ever have reached it; and thus the audience, al

unconsciously, was confronted with the rema