mummy being laid in its original sarcophagus; and a model boat, used in one of the funeral

ceremonies, was left in the tomb. One night the six watchmen who were in charge of the royal

tombs stated that they had been attacked by an armed force; the tomb in question was seen

to have been entered, the iron doors having been forced. The mummy of the Pharaoh was

found lying upon the floor of the burial-hal, its chest smashed in; and the boat had [245]

disappeared, nor has it since been recovered. The watchmen showed signs of having put up

something of a fight, their clothes being riddled with bulet-holes; but here and there the cloth

looked much as though it had been singed, which suggested, as did other evidence, that they

themselves had fired the guns and had acted the struggle. The truth of the matter wil never be

known, but its lesson is obvious. The mummy was put back into its sarcophagus, and there it

has remained secure ever since; but one never knows how soon it wil be dragged forth once

more to be searched for the gold with which every native thinks it is stuffed.

Some years ago an armed gang walked off with a complete series of mortuary reliefs

belonging to a tomb at Sakkârah. They came by night, overpowered the watchmen, loaded

the blocks of stone on to camels, and disappeared into the darkness. Sometimes it is an entire

cemetery that is attacked; and, if it happens to be situated some miles from the nearest police-

station, a good deal of work can be done before the authorities get wind of the affair. Last

winter six hundred men set to work upon a patch of desert ground where a tomb had been

accidently found, and, ere I received the news, they had robbed a score of little graves, many

of which must have contained objects purchasable by the dealers in antiquities for quite large [246]

sums of money. At Abydos a tomb which we had just discovered was raided by the vilagers,

and we only regained possession of it after a rapid exchange of shots, one of which came near

ending a career whose continuance had been, since birth, a matter of great importance to

myself. But how amusing the adventure must have been for the raiders!

The appropriation of treasure-trove come upon by chance, or the digging out of graves

accidentaly discovered, is a very natural form of robbery for the natives to indulge in, and one

which commends itself to the sympathies of al those not actively concerned in its suppression.

There are very few persons even in western countries who would be wiling to hand over to

the Government a hoard of gold discovered in their own back garden. In Egypt the law is that

the treasure-trove thus discovered belongs to the owner of the property; and thus there is

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

125/160

always a certain amount of excavation going on behind the wals of the houses. It is also the

law that the peasants may carry away the accumulated rubbish on the upper layers of ancient

town sites, in order to use it as a fertiliser for their crops, since it contains valuable

phosphates. This work is supervised by watchmen, but this does not prevent the stealing of

almost al the antiquities which are found. As ilegal excavators these sebakhîn, or manure-

diggers, are the worst offenders, for they search for the phosphates in al manner of places, [247]

and are constantly coming upon tombs or ruins which they promptly clear of their contents.

One sees them driving their donkeys along the roads, each laden with a sack of manure, and it

is certain that some of these sacks contain antiquities. In Thebes many of the natives live inside

the tombs of the ancient nobles, these generaly consisting of two or three rock-hewn hals

from which a tunnel leads down to the burial-chamber. Generaly this tunnel is choked with

débris, and the owner of the house wil perhaps come upon it by chance, and wil dig it out, in

the vain hope that earlier plunderers have left some of the antiquities undisturbed. It recently

happened that an entire family was asphyxiated while attempting to penetrate into a newly

discovered tunnel, each member entering to ascertain the fate of the previous explorer, and

each being overcome by the gases. On one occasion I was asked by a native to accompany

him down a tunnel, the entrance of which was in his stable, in order to view a sarcophagus

which lay at the bottom. We each took a candle, and, crouching down to avoid the low roof,

we descended the narrow, winding passage, the loose stones sliding beneath our feet. The air

was very foul; and below us there was the thunderous roar of thousands of wings beating

through the echoing passage—the wings of evil-smeling bats. Presently we reached this

uncomfortable zone. So thickly did the bats hang from the ceiling that the rock itself seemed to [248]

be black; but as we advanced, and the creatures took to their wings, this black covering

appeared to peel off the rock. During the entire descent this curious spectacle of regularly

receding blackness and advancing grey was to be seen a yard or so in front of us. The roar of

wings was now deafening, for the space into which we were driving the bats was very

confined. My guide shouted to me that we must let them pass out of the tomb over our heads.

We therefore crouched down, and a few stones were flung into the darkness ahead. Then,

with a roar and a rush of air, they came, bumping into us, entangling themselves in our clothes,

slapping our faces and hands with their unwholesome wings, and clinging to our fingers. At last

the thunder died away in the passage behind us, and we were able to advance more easily,

though the ground was alive with the bats maimed in the frantic flight which had taken place,

floundering out of our way and squeaking shrily. The sarcophagus proved to be of no interest,

so the encounter with the bats was to no purpose.

The pilfering of antiquities found during the course of authorised excavations is one of the most

common forms of robbery. The overseer cannot always watch the workmen sufficiently

closely to prevent them pocketing the smal objects which they find, and it is an easy matter to

carry off the stolen goods, even though the men are searched at the end of the day. A little girl [249]

minding her father's sheep and goats in the neighbourhood of the excavations, and apparently

occupying her hands with the spinning of flax, is perhaps the receiver of the objects. Thus it is

more profitable to dig for antiquities even in authorised excavations than to work the water-

hoist, which is one of the usual occupations of the peasant. Puling the hoisting-pole down, and

swinging it up again with its load of water many thousands of times in the day, is monotonous

work; whereas digging in the ground, with the eyes keenly watching for the appearance of

antiquities, is always interesting and exciting. And why should the digger refrain from

appropriating the objects which his pick reveals? If he does not make use of his opportunities

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

126/160

and carry off the antiquities, the western director of the works wil take them to his own

country and sel them for his own profit. Al natives believe that the archæologists work for the

purpose of making money. Speaking of Professor Flinders Petrie, a peasant said to me the

other day: "He has worked five-and-twenty years now; he must be very rich." He would

never believe that the antiquities were given to museums without any payment being made to

the finder.

The stealing of fragments broken out of the wals of "show" monuments is almost the only form

of robbery which wil receive general condemnation. That this vandalism is also distasteful to [250]

the natives themselves is shown by the fact that several better-class Egyptians living in the

neighbourhood of Thebes subscribed, at my invitation, the sum of £50 for the protection of

certain beautiful tombs. When they were shown the works undertaken with their money, they

expressed themselves as being "pleased with the delicate inscriptions in the tombs, but very

awfuly angry at the damage which the devils of ignorant people had made." A native of

moderate inteligence can quite appreciate the argument that whereas the continuous warfare

between the agents of the Department of Antiquities and the ilegal excavators of smal graves

is what might be caled an honourable game, the smashing of public monuments cannot be

caled fair-play from whatever point of view the matter is approached. Often revenge or spite

is the cause of this damage. It is sometimes necessary to act with severity to the peasants who

infringe the rules of the Department, but a serious danger lies in such action, for it is the nature

of the Thebans to revenge themselves not on the official directly but on the monuments which

he is known to love. Two years ago a native ilegaly built himself a house on Government

ground, and I was obliged to go through the formality of puling it down, which I did by

obliging him to remove a few layers of brickwork around the wals. A short time afterwards a

famous tomb was broken into and a part of the paintings destroyed; and there was enough [251]

evidence to show that the owner of this house was the culprit, though unfortunately he could

not be convicted. One man actualy had the audacity to warn me that any severity on my part

would be met by destruction of monuments. Under these circumstances an official finds

himself in a dilemma. If he maintains the dignity and prestige of his Department by punishing

any offences against it, he endangers the very objects for the care of which he is responsible;

and it is hard to say whether under a lax or a severe administration the more damage would

be done.

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

127/160

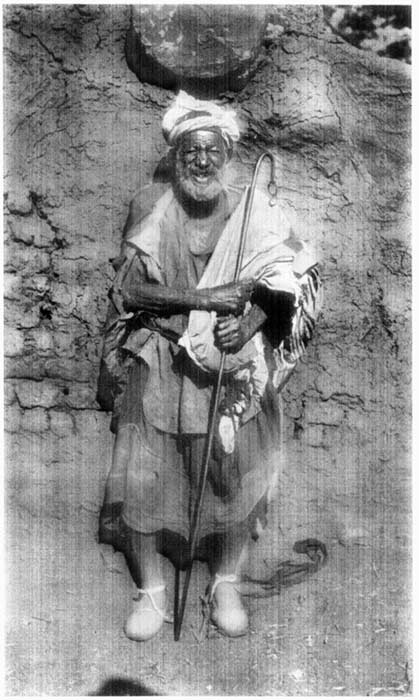

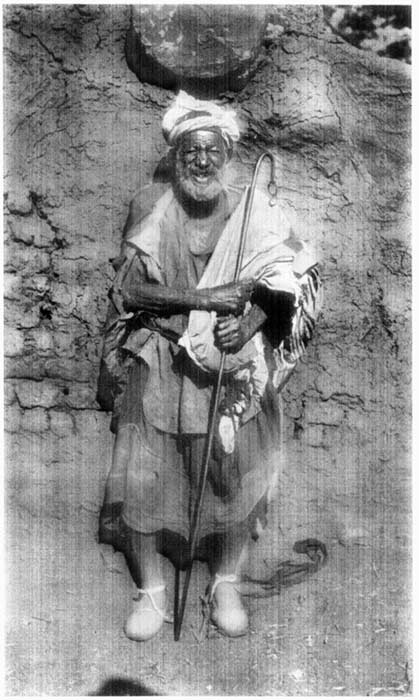

[Photo by E. Bird.

A modern Gournawi beggar.

PL. XXIV.

The produce of these various forms of robbery is easily disposed of. When once the

antiquities have passed into the hands of the dealers there is little chance of further trouble.

The dealer can always say that he came into possession of an object years ago, before the

antiquity laws were made, and it is almost impossible to prove that he did not. You may have

the body of a statue and he the head: he can always damage the line of the breakage, and say

that the head does not belong to that statue, or, if the connection is too obvious, he can say

that he found the head while excavating twenty years ago on the site where now you have

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

128/160

found the body. Nor is it desirable to bring an action against the man in a case of this kind, for

it might go against the official. Dealing in antiquities is regarded as a perfectly honourable

business. The official, crawling about the desert on his stomach in the bitter cold of a winter's [252]

night in order to hold up a convoy of stolen antiquities, may use hard language in regard to the

trade, but he cannot say that it is pernicious as long as it is confined to minor objects. How

many objects of value to science would be destroyed by their finders if there was no market

to take them to! One of the Theban dealers leads so holy a life that he wil assuredly be

regarded as a saint by future generations.

The sale of smal antiquities to tourists on the public roads is prohibited, except at certain

places, but of course it can be done with impunity by the exercise of a little care. Men and

boys and even little girls as they pass wil stare at you with studying eyes, and if you seem to

be a likely purchaser, they wil draw from the folds of their garments some little object which

they wil offer for sale. Along the road in the glory of the setting sun there wil come as fine a

young man as you wil see on a day's march. Surely he is bent on some noble mission: what

lofty thoughts are occupying his mind, you wonder. But as you pass, out comes the scarab

from his pocket, and he shouts, "Wanty scarab, mister?—two shilin'," while you ride on your

way a greater cynic than before.

Some years ago a large inscribed stone was stolen from a certain temple, and was promptly

sold to a man who sometimes traded in such objects. This man carried the stone, hidden in a [253]

sack of grain, to the house of a friend, and having deposited it in a place of hiding, he tramped

home, with his stick across his shoulders, in an attitude of deep unconcern. An enemy of his,

however, had watched him, and promptly gave information. Acting on this the police set out

to search the house. When we reached the entrance we were met by the owner, and a

warrant was shown to him. A heated argument folowed, at the end of which the infuriated

man waved us in with a magnificent and most dramatic gesture. There were some twenty

rooms in the house, and the stifling heat of a July noon made the task none too enjoyable. The

police inspector was extremely thorough in his work, and an hour had passed before three

rooms had been searched. He looked into the cupboards, went down on his knees to peer

into the ovens, stood on tiptoe to search the fragile wooden shelves (it was a heavy stone

which we were looking for), hunted under the mats, and even peeped into a little tobacco-tin.

In one of the rooms there were three or four beds arranged along the middle of the floor. The

inspector puled off the mattresses, and out from under each there leapt a dozen rats, which, if

I may be believed, made for the wals and ran straight up them, disappearing in the rafter-

holes at the top. The sight of countless rats hurrying up perpendicular wals may be familiar to

some people, but I venture to cal it an amazing spectacle, worthy of record. Then came the [254]

opening of one or two traveling-trunks. The inspector ran his hand through the clothes which

lay therein, and out jumped a few more rats, which likewise went up the wals. The searching

of the remaining rooms carried us wel through the afternoon; and at last, hot and weary, we

decided to abandon the hunt. Two nights later a man was seen walking away from the house

with a heavy sack on his back; and the stone is now, no doubt, in the Western hemisphere.

The attempt to regain a lost antiquity is seldom crowned with success. It is so extremely

difficult to obtain reliable information; and as soon as a man is suspected his enemies wil rush

in with accusations. Thirty-eight separate accusations were sent in against a certain head-

watchman during the first days after the fact had leaked out that he was under suspicion. Not

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

129/160

one of them could be shown to be true. Sometimes one man wil bring a charge against

another for the betterment of his own interests. Here is a letter from a watchman who had

resigned, but wished to rejoin, "To his Exec. Chief Dircoter of the tembels. I have honner to

inform that I am your servant X, watchman on the tembels before this time. Sir from one year

ago I work in the Santruple (?) as a watchman about four years ago. And I not make anything

wrong and your Exec. know me. Now I want to work in my place in the tembel, because the

man which in it he not attintive to His, but alway he in the coffee.... He also steal the scribed [255]

stones. Please give your order to point me again. Your servant, X." "The coffee" is, of course,

the café which adjoins the temple.

A short time ago a young man came to me with an accusation against his own father, who, he

said, had stolen a statuette. The tale which he told was circumstantial, but it was hotly denied

by his infuriated parent. He looked, however, a trifle more honest than his father, and when a

younger brother was brought in as witness, one felt that the guilt of the old man would be the

probable finding. The boy stared steadfastly at the ground for some moments, however, and

then launched out into an elaborate explanation of the whole affair. He said that he asked his

father to lend him four pounds, but the father had refused. The son insisted that that sum was

due to him as his share in some transaction, and pointed out that though he only asked for it as

a loan, he had in reality a claim to it. The old man refused to hand it over, and the son,

therefore, waited his opportunity and stole it from his house, carrying it off triumphantly to his

own establishment. Here he gave it into the charge of his young wife, and went about his

business. The father, however, guessed where the money had gone; and while his son was

out, invaded his house, beat his daughter-in-law on the soles of her feet until she confessed

where the money was hidden, and then, having obtained it, returned to his home. When the [256]

son came back to his house he learnt what had happened, and, out of spite, at once invented

the accusation which he had brought to me. This story appeared to be true in so far as the

quarrel over the money was concerned, but that the accusation was invented proved to be

untrue.

Sometimes the peasants have such honest faces that it is difficult to believe that they are guilty

of deceit. A lady came to the camp of a certain party of excavators at Thebes, holding in her

hand a scarab. "Do tel me," she said to one of the archæologists, "whether this scarab is

genuine. I am sure it must be, for I bought it from a boy who assured me that he had stolen it

from your excavations, and he looked such an honest and truthful little felow."

In order to check pilfering in a certain excavation in which I was assisting we made a rule that

the selected workmen should not be alowed to put unselected substitutes in their place. One

day I came upon a man whose appearance did not seem familiar, although his back was

turned to me. I asked him who he was, whereupon he turned upon me a countenance which

might have served for the model of a painting of St John, and in a low, sweet-voice he told me

of the ilness of the real workman, and of how he had taken over the work in order to obtain

money for the purchase of medicine for him, they being friends from their youth up. I sent him

away and told him to cal for any medicine he might want that evening. I did not see him again [257]

until about a week later, when I happened to meet him in the vilage with a policeman on either

side of him, from one of whom I learned that he was a wel-known thief. Thus is one deceived

even in the case of real criminals: how then can one expect to get at the truth when the crime

committed is so light an affair as the stealing of an antiquity?

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

130/160

The folowing is a letter received from one of the greatest thieves in Thebes, who is now

serving a term of imprisonment in the provincial gaol:—

"SIR GENERAL INSPECTOR,—I offer this application stating that I am from

the natives of Gurneh, saying the folowing:—

'On Saturday last I came to your office and have been told that my family using

the sate to strengthen against the Department. The result of this talking that al

these things which somebody pretends are not the fact. In fact I am taking great

care of the antiquities for the purpose of my living matter. Accordingly, I wish to

be appointed in the vacant of watching to the antiquities in my vilage and

promise myself that if anything happens I do hold myself resposible.'"

I have no idea what "using the sate to strengthen" means.

It is sometimes said that European excavators are committing an offence against the

sensibilities of the peasants by digging up the bodies of their ancestors. Nobody wil repeat [258]

this remark who has walked over a cemetery plundered by the natives themselves. Here

bodies may be seen lying in al directions, torn limb from limb by the gold-seekers; here

beautiful vases may be seen smashed to atoms in order to make more rare the specimens

preserved. The peasant has no regard whatsoever for the sanctity of the ancient dead, nor

does any superstition in this regard deter him in his work of destruction. Fortunately

superstition sometimes checks other forms of robbery. Djins are believed to guard the hoards

of ancient wealth which some of the tombs are thought to contain, as, for example, in the case

of the tomb in which the family was asphyxiated, where a fiend of this kind was thought to

have throttled the unfortunate explorers. Twin brothers are thought to have the power of

changing themselves into cats at wil; and a certain Huseyn Osman, a harmless individual

enough, and a most expert digger, would turn himself into a cat at night-time, not only for the

purpose of stealing his brother Muhammed Osman's dinner, but also in order to protect the

tombs which his patron was occupied in excavating. One of the overseers in some recent

excavations was said to have power of detecting al robberies on his works. The

archæologist, however, is unfortunately unable to rely upon this form of protection, and many

are the schemes for the prevention of pilfering which are tried.

In some excavations a sum of money is given to the workman for every antiquity found by [259]

him, and these sums are sufficiently high to prevent any outbidding by the dealers. Work thus

becomes very expensive for the archæologist, who is sometimes caled upon to pay £10 or

£20 in a day. The system has also another disadvantage, namely, that the workmen are apt to

bring antiquities from far and near to "discover" in their diggings in order to obtain a good

price for them. Nevertheless, it would seem to be the most successful of the systems. In the

Government excavations it is usual to employ a number of overseers to watch for the smal

finds, while for only the realy valuable discoveries is a reward given.

For finding the famous gold hawk's head at Hieraconpolis a workman received £14, and with

this princely sum in his pocket he went to a certain Englishman to ask advice as to the

spending of it. He was troubled, he said, to decide whether to buy a wife or a cow. He

admitted that he had already one wife, and that two of them would be sure to introduce some

friction into what was now a peaceful household; and he quite realised that a cow would be

less apt to quarrel with his first wife. The Englishman, very properly, voted for the cow, and

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

131/160

the peasant returned home deep in thought. While pondering over the matter during the next

few weeks, he entertained his friends with some freedom, and soon he found to his dismay

that he had not enough money left to buy either a wife or a cow. Thereupon he set to with a [260]

wil, and soon spent the remaining guineas in riotous living. When he was next seen by the

Englishman he was a beggar, and, what was worse, his taste for evil living had had several

weeks of cultivation.

The case of the fortunate finder of a certain great cache of mummies was different. He

received a reward of £400, and this he buried in a very secret place. When he died his

possessions descended to his sons. After the funeral they sat round the grave of the old man,

and very rightly discussed his virtues until the sun set. Then they returned to the house and

began to dig for the hidden money. For some days they turned the sand of the floor over; but

failing to find what they sought, they commenced operations on a patch of desert under the

shade of some tamarisks where their father was wont to sit of an afternoon. It is said that for

twelve hours they worked like persons possessed, the men hacking at the ground, and the

boys carrying away the sand in baskets to a convenient distance. But the money was never

found.

It is not often that the finders of antiquities inform the authorities of their good fortune, but

when they do so an attempt is made to give them a good reward. A letter from the finder of

an inscribed statue, who wished to claim his reward, read as folows: "With al delight I please

inform you that on 8th Jan. was found a headless temple of granite sitting on a chair and

printed on it."

I wil end this chapter as I began it, in the defence of the Theban thieves. In a place where [261]

every yard of ground contains antiquities, and where these antiquities may be so readily

converted into golden guineas, can one wonder that every man, woman, and child makes use

of his opportunities in this res