to these merchants and entered into conversation with them. Then, suddenly overpowering

them, a rush was made for their cash-box, which Wenamon at once burst open. To his

disappointment he found it to contain only thirty-one debens of silver, which happened to be

precisely the amount of silver, though not of gold, which he had lost. This sum he pocketed,

saying to the struggling merchants as he did so, "I wil take this money of yours, and wil keep [122]

it until you find my money. Was it not a Sicilian who stole it, and no thief of ours? I wil take

it."

With these words the party raced back to the ship, scrambled on board, and in a few

moments had hoisted sail and were scudding northwards towards Byblos, where Wenamon

proposed to throw himself on the mercy of Zakar-Baal, the prince of that city. Wenamon, it

wil be remembered, had always considered that he had been robbed by a Sicilian of Dor,

notwithstanding the fact that only a sailor of his own ship could have known of the existence of

the money, as King Bedel seems to have pointed out to him. The Egyptian, therefore, did not

regard this forcible seizure of silver from these other Sicilians as a crime. It was a perfectly just

appropriation of a portion of the funds which belonged to him by rights. Let us imagine

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

67/160

ourselves robbed at our hotel by Hans the German waiter: it would surely give us the most

profound satisfaction to take Herr Schnupfendorff, the piano-tuner, by the throat when next

he visited us, and go through his pockets. He and Hans, being of the same nationality, must

suffer for one another's sins, and if the magistrate thinks otherwise he must be regarded as

prejudiced by too much study of the law.

Byblos stood at the foot of the hils of Lebanon, in the very shadow of the great cedars, and it

was therefore Wenamon's destination. Now, however, as the ship dropped anchor in the [123]

harbour, the Egyptian realised that his mission would probably be fruitless, and that he himself

would perhaps be flung into prison for ilegaly having in his possession the famous image of

the god to which he could show no written right. Moreover, the news of the robbery of the

merchants might wel have reached Byblos overland. His first action, therefore, was to

conceal the idol and the money; and this having been accomplished he sat himself down in his

cabin to await events.

The Prince of Byblos certainly had been advised of the robbery; and as soon as the news of

the ship's arrival was reported to him he sent a curt message to the captain saying simply, "Get

out of my harbour." At this Wenamon gave up al hope, and, hearing that there was then in

port a vessel which was about to sail for Egypt, he sent a pathetic message to the prince

asking whether he might be alowed to travel by it back to his own country.

No satisfactory answer was received, and for the best part of a month Wenamon's ship rode

at anchor, while the distracted envoy paced the deck, vainly pondering upon a fitting course of

action. Each morning the same brief order, "Get out of my harbour," was delivered to him by

the harbour-master; but the indecision of the authorities as to how to treat this Egyptian official

prevented the order being backed by force. Meanwhile Wenamon and Mengebet judiciously [124]

spread through the city the report of the power of Amon-of-the-Road, and hinted darkly at

the wrath which would ultimately fal upon the heads of those who suffered the image and its

keeper to be turned away from the quays of Byblos. No doubt, also, a portion of the stolen

debens of silver was expended in bribes to the priests of the city, for, as we shal presently

see, one of them took up Wenamon's cause with the most unnatural vigour.

Al, however, seemed to be of no avail, and Wenamon decided to get away as best he could.

His worldly goods were quietly transferred to the ship which was bound for the Nile; and,

when night had falen, with Amon-of-the-Road tucked under his arm, he hurried along the

deserted quay. Suddenly out of the darkness there appeared a group of figures, and

Wenamon found himself confronted by the stalwart harbour-master and his police. Now,

indeed, he gave himself up for lost. The image would be taken from him, and no longer would

he have the alternative of leaving the harbour. He must have groaned aloud as he stood there

in the black night, with the cold sea wind threatening to tear the covers from the treasure

under his arm. His surprise, therefore, was unbounded when the harbour-master addressed

him in the folowing words: "Remain until morning here near the prince."

The Egyptian turned upon him fiercely. "Are you not the man who came to me every day

saying, "Get out of my harbour?" he cried. "And now are you not saying, 'Remain in Byblos?' [125]

your object being to let this ship which I have found depart for Egypt without me, so that you

may come to me again and say, 'Go away.'"

The harbour-master in reality had been ordered to detain Wenamon for quite another reason.

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

68/160

On the previous day, while the prince was sacrificing to his gods, one of the noble youths in

his train, who had probably seen the colour of Wenamon's debens, suddenly broke into a

religious frenzy, and so continued al that day, and far into the night, caling incessantly upon

those around him to go and fetch the envoy of Amon-Ra and the sacred image. Prince Zakar-

Baal had considered it prudent to obey this apparently divine command, and had sent the

harbour-master to prevent Wenamon's departure. Finding, however, that the Egyptian was

determined to board the ship, the official sent a messenger to the prince, who replied with an

order to the skipper of the vessel to remain that night in harbour.

Upon the folowing morning a deputation, evidently friendly, waited on Wenamon, and urged

him to come to the palace, which he finaly did, incidentaly attending on his way the morning

service which was being celebrated upon the sea-shore. "I found the prince," writes

Wenamon in his report, "sitting in his upper chamber, leaning his back against a window, while

the waves of the Great Syrian Sea beat against the wal below. I said to him, 'The mercy of [126]

Amon be with you!' He said to me, 'How long is it from now since you left the abode of

Amon?' I replied, 'Five months and one day from now.'"

The prince then said, "Look now, if what you say is true, where is the writing of Amon which

should be in your hand? Where is the letter of the High Priest of Amon which should be in

your hand?"

"I gave them to Nesubanebded," replied Wenamon.

"Then," says Wenamon, "he was very wroth, and he said to me, 'Look here, the writings and

the letters are not in your hand. And where is the fine ship which Nesubanebded would have

given you, and where is its picked Syrian crew? He would not put you and your affairs in the

charge of this skipper of yours, who might have had you kiled and thrown into the sea.

Whom would they have sought the god from then?—and you, whom would they have sought

you from then?' So said he to me, and I replied to him, 'There are indeed Egyptian ships and

Egyptian crews that sail under Nesubanebded, but he had at the time no ship and no Syrian

crew to give me.'"

The prince did not accept this as a satisfactory answer, but pointed out that there were ten

thousand ships sailing between Egypt and Syria, of which number there must have been one at

Nesubanebded's disposal.

"Then," writes Wenamon, "I was silent in this great hour. At length he said to me, 'On what [127]

business have you come here?' I replied, 'I have come to get wood for the great and august

barge of Amon-Ra, king of the gods. Your father supplied it, your grandfather did so, and you

too shal do it.' So spoke I to him."

The prince admitted that his fathers had sent wood to Egypt, but he pointed out that they had

received proper remuneration for it. He then told his servants to go and find the old ledger in

which the transactions were recorded, and this being done, it was found that a thousand

debens of silver had been paid for the wood. The prince now argued that he was in no way

the servant of Amon, for if he had been he would have been obliged to supply the wood

without remuneration. "I am," he proudly declared, "neither your servant nor the servant of him

who sent you here. If I cry out to the Lebanon the heavens open and the logs lie here on the

shore of the sea." He went on to say that if, of his condescension, he now procured the timber

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

69/160

Wenamon would have to provide the ships and al the tackle. "If I make the sails of the ships

for you," said the prince, "they may be top-heavy and may break, and you wil perish in the

sea when Amon thunders in heaven; for skiled workmanship comes only from Egypt to reach

my place of abode." This seems to have upset the composure of Wenamon to some extent,

and the prince took advantage of his uneasiness to say, "Anyway, what is this miserable [128]

expedition that they have had you make (without money or equipment)?"

At this Wenamon appears to have lost his temper. "O guilty one!" he said to the prince, "this is

no miserable expedition on which I am engaged. There is no ship upon the Nile which Amon

does not own, and his is the sea, and his this Lebanon of which you say, 'It is mine.' Its forests

grow for the barge of Amon, the lord of every ship. Why Amon-Ra himself, the king of the

gods, said to Herhor, my lord, 'Send me'; and Herhor made me go bearing the statue of this

great god. Yet see, you have alowed this great god to wait twenty-nine days after he had

arrived in your harbour, although you certainly knew he was there. He is indeed stil what he

once was: yes, now while you stand bargaining for the Lebanon with Amon its lord. As for

Amon-Ra, the king of the gods, he is the lord of life and health, and he was the lord of your

fathers, who spent their lifetime offering to him. You also, you are the servant of Amon. If you

wil say to Amon, 'I wil do this,' and you execute his command, you shal live and be

prosperous and be healthy, and you shal be popular with your whole country and people.

Wish not for yourself a thing belonging to Amon-Ra, king of the gods. Truly the lion loves his

own! Let my secretary be brought to me that I may send him to Nesubanebded, and he wil

send you al that I shal ask him to send, after which, when I return to the south, I wil send [129]

you al, al your trifles again."

"So spake I to him," says Wenamon in his report, as with a flourish of his pen he brings this

fine speech to an end. No doubt it would have been more truthful in him to say, "So would I

have spoken to him had I not been so flustered"; but of al types of lie this is probably the

most excusable. At al events, he said sufficient to induce the prince to send his secretary to

Egypt; and as a token of good faith Zakar-Baal sent with him seven logs of cedar-wood. In

forty-eight days' time the messenger returned, bringing with him five golden and five silver

vases, twenty garments of fine linen, 500 rols of papyrus, 500 ox-hides, 500 coils of rope,

twenty measures of lentils, and five measures of dried fish. At this present the prince

expressed himself most satisfied, and immediately sent 300 men and 300 oxen with proper

overseers to start the work of feling the trees. Some eight months after leaving Tanis,

Wenamon's delighted eyes gazed upon the complete number of logs lying at the edge of the

sea, ready for shipment to Egypt.

The task being finished, the prince walked down to the beach to inspect the timber, and he

caled to Wenamon to come with him. When the Egyptian had approached, the prince pointed

to the logs, remarking that the work had been carried through although the remuneration had

not been nearly so great as that which his fathers had received. Wenamon was about to reply [130]

when inadvertently the shadow of the prince's umbrela fel upon his head. What memories or

anticipations this trivial incident aroused one cannot now tel with certainty. One of the

gentlemen-in-waiting, however, found cause in it to whisper to Wenamon, "The shadow of

Pharaoh, your lord, fals upon you"—the remark, no doubt, being accompanied by a sly dig in

the ribs. The prince angrily snapped, "Let him alone"; and, with the picture of Wenamon

gloomily staring out to sea, we are left to worry out the meaning of the occurrence. It may be

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

70/160

that the prince intended to keep Wenamon at Byblos until the uttermost farthing had been

extracted from Egypt in further payment for the wood, and that therefore he was to be

regarded henceforth as Wenamon's king and master. This is perhaps indicated by the

folowing remarks of the prince.

"Do not thus contemplate the terrors of the sea," he said to Wenamon. "For if you do that you

should also contemplate my own. Come, I have not done to you what they did to certain

former envoys. They spent seventeen years in this land, and they died where they were."

Then, turning to an attendant, "Take him," he said, "and let him see the tomb in which they lie."

"Oh, don't let me see it," Wenamon tels us that he cried in anguish; but, recovering his

composure, he continued in a more valiant strain. "Mere human beings," he said, "were the [131]

envoys who were then sent. There was no god among them (as there now is)."

The prince had recently ordered an engraver to write a commemorative inscription upon a

stone tablet recording the fact that the king of the gods had sent Amon-of-the-Road to Byblos

as his divine messenger and Wenamon as his human messenger, that timber had been asked

for and supplied, and that in return Amon had promised him ten thousand years of celestial life

over and above that of ordinary persons. Wenamon now reminded him of this, asking him

why he should talk so slightingly of the Egyptian envoys when the making of this tablet showed

that in reality he considered their presence an honour. Moreover, he pointed out that when in

future years an envoy from Egypt should read this tablet, he would of course pronounce at

once the magical prayers which would procure for the prince, who would probably then be in

hel after al, a draught of water. This remark seems to have tickled the prince's fancy, for he

gravely acknowledged its value, and spoke no more in his former strain. Wenamon closed the

interview by promising that the High Priest of Amon-Ra would fuly reward him for his various

kindnesses.

Shortly after this the Egyptian paid another visit to the sea-shore to feast his eyes upon the

logs. He must have been almost unable to contain himself in the delight and excitement of the

ending of his task and his approaching return, in triumph to Egypt; and we may see him [132]

jauntily walking over the sand, perhaps humming a tune to himself. Suddenly he observed a

fleet of eleven ships sailing towards the town, and the song must have died upon his lips. As

they drew nearer he saw to his horror that they belonged to the Sicilians of Dor, and we must

picture him biting his nails in his anxiety as he stood amongst the logs. Presently they were

within hailing distance, and some one caled to them asking their business. The reply rang

across the water, brief and terrible; "Arrest Wenamon! Let not a ship of his pass to Egypt."

Hearing these words the envoy of Amon-Ra, king of the gods, just now so proudly boasting,

threw himself upon the sand and burst into tears.

The sobs of the wretched man penetrated to a chamber in which the prince's secretary sat

writing at the open window, and he hurried over to the prostrate figure. "Whatever is the

matter with you?" he said, tapping the man on the shoulder.

Wenamon raised his head, "Surely you see these birds which descend on Egypt," he groaned.

"Look at them! They have come into the harbour, and how long shal I be left forsaken here?

Truly you see those who have come to arrest me."

With these words one must suppose that Wenamon returned to his weeping, for he says in his

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

71/160

report that the sympathetic secretary went off to find the prince in order that some plan of [133]

action might be formulated. When the news was reported to Zakar-Baal, he too began to

lament; for the whole affair was menacing and ugly. Looking out of the window he saw the

Sicilian ships anchored as a barrier across the mouth of the harbour, he saw the logs of cedar-

wood strewn over the beach, he saw the writhing figure of Wenamon pouring sand and dust

upon his head and drumming feebly with his toes; and his royal heart was moved with pity for

the misfortunes of the Egyptian.

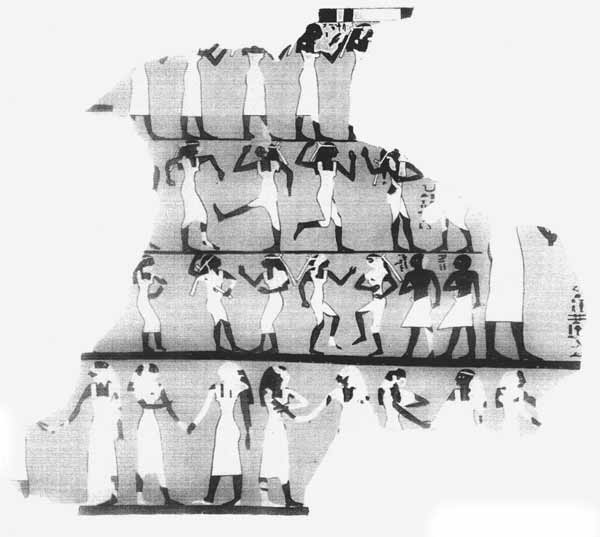

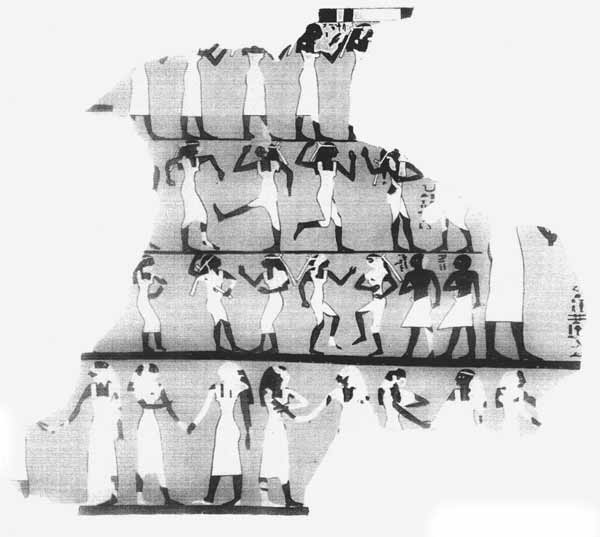

[Copied by H. Petrie.

A festival scene of singers and dancers from a tomb-painting of Dynasty XVII.—THEBES.

PL. XIII.

Hastily speaking to his secretary, he told him to procure two large jars of wine and a ram, and

to give them to Wenamon on the chance that they might stop the noise of his lamentations.

The secretary and his servants procured these things from the kitchen, and, tottering down

with them to the envoy, placed them by his side. Wenamon, however, merely glanced at them

in a sickly manner, and then buried his head once more. The failure must have been observed

from the window of the palace, for the prince sent another servant flying off for a popular

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

72/160

Egyptian lady of no reputation, who happened to be living just then at Byblos in the capacity

of a dancing-girl. Presently she minced into the room, very much elated, no doubt, at this

indication of the royal favour. The prince at once ordered her to hasten down on to the beach

to comfort her countryman. "Sing to him," he said. "Don't let his heart feel apprehension."

Wenamon seemed to have waved the girl aside, and we may picture the prince making urgent [134]

signs to the lady from his window to renew her efforts. The moans of the miserable man,

however, did not cease, and the prince had recourse to a third device. This time he sent a

servant to Wenamon with a message of calm assurance. "Eat and drink," he said, "and let not

your heart feel apprehension. You shal hear al that I have to say in the morning." At this

Wenamon roused himself, and, wiping his eyes, consented to be led back to his rooms, ever

turning, no doubt, to cast nervous glances in the direction of the silent ships of Dor.

On the folowing morning the prince sent for the leaders of the Sicilians and asked them for

what reason they had come to Byblos. They replied that they had come in search of

Wenamon, who had robbed some of their countrymen of thirty-one debens of silver. The

prince was placed in a difficult position, for he was desirous to avoid giving offence either to

Dor or to Egypt from whence he now expected further payment; but he managed to pass out

on to clearer ground by means of a simple stratagem.

"I cannot arrest the envoy of Amon in my territory," he said to the men of Dor. "But I wil send

him away, and you shal pursue him and arrest him."

The plan seems to have appealed to the sporting instincts of the Sicilians, for it appears that

they drew off from the harbour to await their quarry. Wenamon was then informed of the

scheme, and one may suppose that he showed no relish for it. To be chased across a bilious [135]

sea by sporting men of hardened stomach was surely a torture for the damned; but it is to be

presumed that Zakar-Baal left the Egyptian some chance of escape. Hastily he was conveyed

on board a ship, and his misery must have been complete when he observed that outside the

harbour it was blowing a gale. Hardly had he set out into the "Great Syrian Sea" before a

terrific storm burst, and in the confusion which ensued we lose sight of the waiting fleet. No

doubt the Sicilians put in to Byblos once more for shelter, and deemed Wenamon at the

bottom of the ocean as the wind whistled through their own bare rigging.

The Egyptian had planned to avoid his enemies by beating northwards when he left the

harbour, instead of southwards towards Egypt; but the tempest took the ship's course into its

own hands and drove the frail craft north-westwards towards Cyprus, the wooded shores of

which were, in course of time, sighted. Wenamon was now indeed 'twixt the devil and the

deep sea, for behind him the waves raged furiously, and before him he perceived a threatening

group of Cypriots awaiting him upon the wind-swept shore. Presently the vessel grounded

upon the beach, and immediately the il-starred Egyptian and the entire crew were prisoners in

the hands of a hostile mob. Roughly they were dragged to the capital of the island, which

happened to be but a few miles distant, and with ignominy they were hustled, wet and

bedraggled, through the streets towards the palace of Hetebe, the Queen of Cyprus.

[136]

As they neared the building the queen herself passed by, surrounded by a brave company of

nobles and soldiers. Wenamon burst away from his captors, and bowed himself before the

royal lady, crying as he did so, "Surely there is somebody amongst this company who

understands Egyptian." One of the nobles, to Wenamon's joy, replied, "Yes, I understand it."

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

73/160

"Say to my mistress," cried the tattered envoy, "that I have heard even in far-off Thebes, the

abode of Amon, that in every city injustice is done, but that justice obtains in the land of

Cyprus. Yet see, injustice is done here also this day."

This was repeated to the queen, who replied, "Indeed!—what is this that you say?"

Through the interpreter Wenamon then addressed himself to Hetebe. "If the sea raged," he

said, "and the wind drove me to the land where I now am, wil you let these people take

advantage of it to murder me, I who am an envoy of Amon? I am one for whom they wil seek

unceasingly. And as for these sailors of the prince of Byblos, whom they also wish to kil, their

lord wil undoubtedly capture ten crews of yours, and wil slay every man of them in revenge."

This seems to have impressed the queen, for she ordered the mob to stand on one side, and

to Wenamon she said, "Pass the night ..."

Here the torn writing comes to an abrupt end, and the remainder of Wenamon's adventures [137]

are for ever lost amidst the dust of El Hibeh. One may suppose that Hetebe took the Egyptian

under her protection, and that ultimately he arrived once more in Egypt, whither Zakar-Baal

had perhaps already sent the timber. Returning to his native town, it seems that Wenamon

wrote his report, which for some reason or other was never despatched to the High Priest.

Perhaps the envoy was himself sent for, and thus his report was rendered useless; or perhaps

our text is one of several copies.

There can be no question that he was a writer of great power, and this tale of his adventures

must be regarded as one of the jewels of the ancient Egyptian language. The brief description

of the Prince of Byblos, seated with his back to the window, while the waves beat against the

wal below, brings vividly before one that far-off scene, and reveals a lightness of touch most

unusual in writers of that time. There is surely, too, an appreciation of a delicate form of

humour observable in his account of some of his dealings with the prince. It is appaling to

think that the peasants who found this rol of papyrus might have used it as fuel for their

evening fire; and that, had not a drifting rumour of the value of such articles reached their

vilage, this little tale of old Egypt and the long-lost Kingdoms of the Sea would have gone up

to empty heaven in a puff of smoke.

[TABLE OF CONTENTS]

CHAPTER VI.

[138]

THE STORY OF THE SHIPWRECKED SAILOR.

When the early Spanish explorers led their expeditions to Florida, it was their intention to find

the Fountain of Perpetual Youth, tales of its potent waters having reached Peter Martyr as

early as 1511. This desire to discover the things pertaining to Fairyland has been, throughout

history, one of the most fertile sources of adventure. From the days when