ship moving over the fairy seas.

"So sailed we northwards," said the sailor, "to the place of the Sovereign, and we reached

home in two months, in accordance with al that he had said. And I entered in before the

Sovereign, and I brought to him this tribute which I had taken away from within this island.

Then gave he thanksgivings for me before the magistrates of the entire land. And I was made

a 'Folower,' and was rewarded with the serfs of such an one."

The old sailor turned to the gloomy prince as he brought his story to an end. "Look at me," he

exclaimed, "now that I have reached land, now that I have seen (again in memory) what I

have experienced. Hearken thou to me, for behold, to hearken is good for men."

But the prince only sighed the more deeply, and, with a despairing gesture, replied: "Be not

(so) superior, my friend! Doth one give water to a bird on the eve, when it is to be slain on the

morrow?" With these words the manuscript abruptly ends, and we are supposed to leave the [162]

prince stil disconsolate in his cabin, while his friend, unable to cheer him, returns to his duties

on deck.

[TABLE OF CONTENTS]

PART III.

[163]

RESEARCHES IN THE TREASURY.

"...And he, shall be,

Man, her last work, who seem'd so fair,

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

86/160

Such splendid purpose in his eyes,

Who roll'd the psalm to wintry skies,

Who built him fanes of fruitless prayer,

Who loved, who suffered countless ills,

Who battled for the True, the Just,

Be blown about the desert dust,

Or seal'd within the iron hills?"

—TENNYSON.

CHAPTER VII.

[165]

RECENT EXCAVATIONS IN EGYPT.

There came to the camp of a certain professor, who was engaged in excavating the ruins of an

ancient Egyptian city, a young and faultlessly-attired Englishman, whose thirst for dramatic

adventure had led him to offer his services as an unpaid assistant digger. This immaculate

personage had read in novels and tales many an account of the wonders which the spade of

the excavator could reveal, and he firmly believed that it was only necessary to set a "nigger"

to dig a little hole in the ground to open the way to the treasuries of the Pharaohs. Gold, silver,

and precious stones gleamed before him, in his imagination, as he hurried along subterranean

passages to the vaults of long-dead kings. He expected to slide upon the seat of his very wel-

made breeches down the staircase of the ruined palace which he had entered by way of the

skylight, and to find himself, at the bottom, in the presence of the bejeweled dead. In the

intervals between such experiences he was of opinion that a little quiet gazele shooting would

agreeably fil in the swiftly passing hours; and at the end of the season's work he pictured [166]

himself returning to the bosom of his family with such a tale to tel that every ear would be

opened to him.

On his arrival at the camp he was conducted to the site of his future labours; and his horrified

gaze was directed over a large area of mud-pie, knee-deep in which a few bedraggled natives

slushed their way downwards. After three weeks' work on this distressing site, the professor

announced that he had managed to trace through the mud the outline of the palace wals, once

the feature of the city, and that the work here might now be regarded as finished. He was then

conducted to a desolate spot in the desert, and until the day on which he fled back to England

he was kept to the monotonous task of superintending a gang of natives whose sole business it

was to dig a very large hole in the sand, day after day and week after week.

It is, however, sometimes the fortune of the excavator to make a discovery which almost

rivals in dramatic interest the tales of his youth. Such as experience fel to the lot of Emil

Brugsch Pasha when he was lowered into an ancient tomb and found himself face to face with

a score of the Pharaohs of Egypt, each lying in his coffin; or again, when Monsieur de Morgan

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

87/160

discovered the great mass of royal jewels in one of the pyramids at Dachour. But such "finds"

can be counted on the fingers, and more often an excavation is a fruitless drudgery. [167]

Moreover, the life of the digger is not often a pleasant one.

[Photo by the Author.

The excavations on the site of the city of Abydos.

PL. XVI.

It wil perhaps be of interest to the reader of romances to ilustrate the above remarks by the

narration of some of my own experiences; but there are only a few interesting and unusual

episodes in which I have had the peculiarly good fortune to be an actor. There wil probably

be some drama to be felt in the account of the more important discoveries (for there certainly

is to the antiquarian himself); but it should be pointed out that the interest of these rare finds

pales before the description, which many of us have heard, of how the archæologists of a past

century discovered the body of Charlemagne clad in his royal robes and seated upon his

throne,—which, by the way, is quite untrue. In spite of al that is said to the contrary, truth is

seldom stranger than fiction; and the reader who desires to be told of the discovery of buried

cities whose streets are paved with gold should take warning in time and return at once to his

novels.

If the dawning interest of the reader has now been thoroughly cooled by these words, it may

be presumed that it wil be utterly annihilated by the folowing narration of my first fruitless

excavation; and thus one wil be able to continue the story with the relieved consciousness that

nobody is attending.

In the capacity of assistant to Professor Flinders Petrie, I was set, many years ago, to the task

[168]

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

88/160

of excavating a supposed royal cemetery in the desert behind the ancient city of Abydos, in

Upper Egypt. Two mounds were first attacked; and after many weeks of work in digging

through the sand, the superstructure of two great tombs was bared. In the case of the first of

these several fine passages of good masonry were cleared, and at last the burial-chamber was

reached. In the huge sarcophagus which was there found great hopes were entertained that

the body and funeral-offerings of the dead prince would be discovered; but when at last the

interior was laid bare the solitary article found was a copy of a French newspaper left behind

by the last, and equaly disgusted, excavator. The second tomb defied the most ardent

exploration, and failed to show any traces of a burial. The mystery was at last solved by

Professor Petrie, who, with his usual keen perception, soon came to the conclusion that the

whole tomb was a dummy, built solely to hide an enormous mass of rock chippings the

presence of which had been a puzzle for some time. These masons' chippings were evidently

the output from some large cutting in the rock, and it became apparent that there must be a

great rock tomb in the neighbourhood. Trial trenches in the vicinity presently revealed the

existence of a long wal, which, being folowed in either direction, proved to be the boundary

of a vast court or enclosure built upon the desert at the foot of a conspicuous cliff. A ramp led

up to the entrance; but as it was slightly askew and pointed to the southern end of the [169]

enclosure, it was supposed that the rock tomb, which presumably ran into the cliff from

somewhere inside this area, was situated at that end. The next few weeks were occupied in

the tedious task of probing the sand hereabouts, and at length in clearing it away altogether

down to the surface of the underlying rock. Nothing was found, however; and sadly we

turned to the exact middle of the court, and began to work slowly to the foot of the cliff. Here,

in the very middle of the back wal, a pilared chamber was found, and it seemed certain that

the entrance to the tomb would now be discovered.

The best men were placed to dig out this chamber, and the excavator—it was many years ago

—went about his work with the weight of fame upon his shoulders and an expression of

intense mystery upon his sorely sun-scorched face. How clearly memory recals the letter

home that week, "We are on the eve of a great discovery"; and how vividly rises the picture of

the baking desert sand into which the sweating workmen were slowly digging their way! But

our hopes were short-lived, for it very soon became apparent that there was no tomb

entrance in this part of the enclosure. There remained the north end of the area, and on to this

al the available men were turned. Deeper and deeper they dug their way, until the mounds of

sand thrown out formed, as it were, the lip of a great crater. At last, some forty or fifty feet [170]

down, the underlying rock was struck, and presently the mouth of a great shaft was exposed

leading down into the bowels of the earth. The royal tomb had at last been discovered, and it

only remained to effect an entrance. The days were now filed with excitement, and, the

thoughts being concentrated on the question of the identity of the royal occupant of the tomb,

it was soon fixed in our minds that we were about to enter the burial-place of no less a

personage than the great Pharaoh Senusert III. (Sesostris), the same king whose jewels were

found at Dachour.

One evening, just after I had left the work, the men came down to the distant camp to say that

the last barrier was now reached and that an entrance could be effected at once. In the pale

light of the moon, therefore, I hastened back to the desert with a few trusted men. As we

walked along, one of these natives very cheerfuly remarked that we should al probably get

our throats cut, as the brigands of the neighbourhood got wind of the discovery, and were

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

89/160

sure to attempt to enter the tomb that night. With this pleasing prospect before us we walked

with caution over the silent desert. Reaching the mound of sand which surrounded our

excavation, we crept to the top and peeped over into the crater. At once we observed a dim

light below us, and almost immediately an agitated but polite voice from the opposite mound [171]

caled out in Arabic, "Go away, mister. We have al got guns." This remark was folowed by a

shot which whistled past me; and therewith I slid down the hil once more, and heartily wished

myself safe in my bed. Our party then spread round the crater, and at a given word we

proposed to rush the place. But the enemy was too quick for us, and after the briefest

scrimmage, and the exchanging of a harmless shot or two, we found ourselves in possession

of the tomb, and were able to pretend that we were not a bit frightened.

Then into the dark depths of the shaft we descended, and ascertained that the robbers had

not effected an entrance. A long night watch folowed, and the next day we had the

satisfaction of arresting some of the criminals. The tomb was found to penetrate several

hundred feet into the cliff, and at the end of the long and beautifuly worked passage the great

royal sarcophagus was found—empty! So ended a very strenuous season's work.

If the experiences of a digger in Professor Petrie's camp are to be regarded as typical, they

wil probably serve to damp the ardour of eager young gentlemen in search of ancient

Egyptian treasure. One lives in a bare little hut constructed of mud, and roofed with cornstalks

or corrugated iron; and if by chance there happened to be a rain storm, as there was when I

was a member of the community, one may watch the frail building gently subside in a liquid [172]

stream on to one's bed and books. For seven days in the week one's work continues, and it is

only to the real enthusiast that that work is not monotonous and tiresome.

A few years later it fel to my lot to excavate for the Government the funeral temple of

Thutmosis III. at Thebes, and a fairly large sum was spent upon the undertaking. Although the

site was most promising in appearances, a couple of months' work brought to light hardly a

single object of importance, whereas exactly similar sites in the same neighbourhood had

produced inscriptions of the greatest value. Two years ago I assisted at an excavation upon a

site of my own selection, the net result of which, after six weeks' work, was one mummified

cat! To sit over the work day after day, as did the unfortunate promoter of this particular

enterprise, with the flies buzzing around his face and the sun blazing down upon him from a

relentless sky, was hardly a pleasurable task; and to watch the clouds of dust go up from the

tip-heap, where tons of unprofitable rubbish roled down the hilside al day long, was an

occupation for the damned. Yet that is excavating as it is usualy found to be.

Now let us consider the other side of the story. In the Valey of the Tombs of the Kings at

Thebes excavations have been conducted for some years by Mr Theodore M. Davis, of

Newport, Rhode Island, by special arrangement with the Department of Antiquities of the [173]

Egyptian Government; and as an official of that Department I have had the privilege of being

present at al the recent discoveries. The finding of the tomb of Yuaa and Tuau a few years

ago was one of the most interesting archæological events of recent times, and one which came

somewhere near to the standard of romance set by the novelists. Yuaa and Tuau were the

parents of Queen Tiy, the discovery of whose tomb is recorded in the next chapter. When the

entrance of their tomb was cleared, a flight of steps was exposed, leading down to a passage

blocked by a wal of loose stones. In the top right-hand corner a smal hole, large enough to

admit a man, had been made in ancient times, and through this we could look down into a

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

90/160

dark passage. As it was too late in the day to enter at once, we postponed that exciting

experience until the morrow, and some police were sent for to guard the entrance during the

night. I had slept the previous night over the mouth, and there was now no possibility of

leaving the place for several more nights, so a rough camp was formed on the spot.

Here I settled myself down for the long watch, and speculated on the events of the next

morning, when Mr Davis and one or two wel-known Egyptologists were to come to the

valey to open the sepulchre. Presently, in the silent darkness, a slight noise was heard on the

hilside, and immediately the chalenge of the sentry rang out. This was answered by a distant [174]

cal, and after some moments of alertness on our part we observed two figures approaching

us. These, to my surprise, proved to be a wel-known American artist and his wife,[1] who had

obviously come on the expectation that trouble was ahead; but though in this they were

certainly destined to suffer disappointment, stil, out of respect for the absolute unconcern of

both visitors, it may be mentioned that the mouth of a lonely tomb already said by native

rumour to contain incalculable wealth is not perhaps the safest place in the world. Here, then,

on a level patch of rock we three lay down and slept fitfuly until the dawn. Soon after

breakfast the wal at the mouth of the tomb was puled down, and the party passed into the

low passage which sloped down to the burial chamber. At the bottom of this passage there

was a second wal blocking the way; but when a few layers had been taken off the top we

were able to climb, one by one, into the chamber.

[1] Mr and Mrs Joseph Lindon Smith.

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

91/160

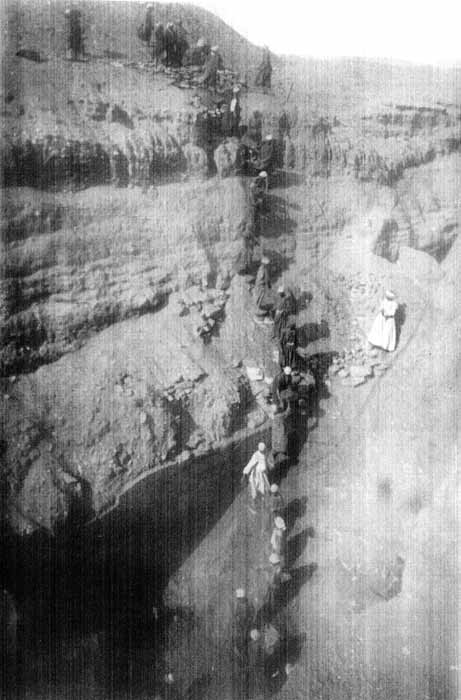

[Photo by the Author.

Excavating the Osireion at Abydos. A chain of boys handing up baskets of sand

to the surface.

PL. XVII.

Imagine entering a town house which had been closed for the summer: imagine the stuffy

room, the stiff, silent appearance of the furniture, the feeling that some ghostly occupants of

the vacant chairs have just been disturbed, the desire to throw open the windows to let life

into room once more. That was perhaps the first sensation as we stood, realy dumfounded,

and stared around at the relics of the life of over three thousand years ago, al of which were [175]

as new almost as when they graced the palace of Prince Yuaa. Three arm-chairs were

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

92/160

perhaps the first objects to attract the attention: beautiful carved wooden chairs, decorated

with gold. Belonging to one of these was a pilow made of down and covered with linen. It

was so perfectly preserved that one might have sat upon it or tossed it from this chair to that

without doing it injury. Here were fine alabaster vases, and in one of these we were startled to

find a liquid, like honey or syrup, stil unsolidified by time. Boxes of exquisite workmanship

stood in various parts of the room, some resting on delicately wrought legs. Now the eye was

directed to a wicker trunk fitted with trays and partitions, and ventilated with little apertures,

since the scents were doubtless strong. Two most comfortable beds were to be observed,

fitted with springy string mattresses and decorated with charming designs in gold. There in the

far corner, placed upon the top of a number of large white jars, stood the light chariot which

Yuaa had owned in his lifetime. In al directions stood objects gleaming with gold unduled by

a speck of dust, and one looked from one article to another with the feeling that the entire

human conception of Time was wrong. These were the things of yesterday, of a year or so

ago. Why, here were meats prepared for the feasts in the Underworld; here were Yuaa's [176]

favourite joints, each neatly placed in a wooden box as though for a journey. Here was his

staff, and here were his sandals,—a new pair and an old. In another corner there stood the

magical figures by the power of which the prince was to make his way through Hades. The

words of the mystical "Chapter of the Flame" and of the "Chapter of the Magical Figure of the

North Wal" were inscribed upon them; and upon a great rol of papyrus twenty-two yards in

length other efficacious prayers were written.

But though the eyes passed from object to object, they ever returned to the two lidless gilded

coffins in which the owners of this room of the dead lay as though peacefuly sleeping. First

above Yuaa and then above his wife the electric lamps were held, and as one looked down

into their quiet faces there was almost the feeling that they would presently open their eyes and

blink at the light. The stern features of the old man commanded one's attention, again and

again our gaze was turned from this mass of wealth to this sleeping figure in whose honour it

had been placed here.

At last we returned to the surface to alow the thoughts opportunity to colect themselves and

the pulses time to quiet down, for, even to the most unemotional, a discovery of this kind,

bringing one into the very presence of the past, has realy an unsteadying effect. Then once

more we descended, and made the preliminary arrangements for the cataloguing of the [177]

antiquities. It was now that the real work began, and, once the excitement was past, there was

a monotony of labour to be faced which put a very considerable strain on the powers of al

concerned. The hot days when one sweated over the heavy packing-cases, and the bitterly

cold nights when one lay at the mouth of the tomb under the stars, dragged on for many a

week; and when at last the long train of boxes was carried down to the Nile en route for the

Cairo Museum, it was with a sigh of relief that the official returned to his regular work.

This, of course, was a very exceptional discovery. Mr Davis has made other great finds, but

to me they have not equaled in dramatic interest the discovery just recorded. Even in this

royal valey, however, there is much drudgery to be faced, and for a large part of the season's

work it is the excavator's business to turn over endless masses of rock chippings, and to dig

huge holes which have no interest for the patient digger. Sometimes the mouth of a tomb is

bared, and is entered with the profoundest hopes, which are at once dashed by the sudden

abrupt ending of the cutting a few yards from the surface. At other times a tomb-chamber is

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

93/160

reached and is found to be absolutely empty.

At another part of Thebes the wel-known Egyptologist, Professor Schiapareli, had

excavated for a number of years without finding anything of much importance, when suddenly

one fine day he struck the mouth of a large tomb which was evidently intact. I was at once [178]

informed of the discovery, and proceeded to the spot as quickly as possible. The mouth of the

tomb was approached down a flight of steep, rough steps, stil half-choked with débris. At

the bottom of this the entrance of a passage running into the hilside was blocked by a wal of

rough stones. After photographing and removing this, we found ourselves in a long, low

tunnel, blocked by a second wal a few yards ahead. Both these wals were intact, and we

realised that we were about to see what probably no living man had ever seen before: the

absolutely intact remains of a rich Theban of the Imperial Age— i.e. , about 1200 or 1300

B.C. When this second wal was taken down we passed into a carefuly-cut passage high

enough to permit of one standing upright.

At the end of this passage a plain wooden door barred our progress. The wood retained the

light colour of fresh deal, and looked for al the world as though it had been set up but

yesterday. A heavy wooden lock, such as is used at the present day, held the door fast. A

neat bronze handle on the side of the door was connected by a spring to a wooden knob set

in the masonry door-post; and this spring was carefuly sealed with a smal dab of stamped

clay. The whole contrivance seemed so modern that Professor Schiapareli caled to his

servant for the key, who quite seriously replied, "I don't know where it is, sir." He then [179]

thumped the door with his hand to see whether it would be likely to give; and, as the echoes

reverberated through the tomb, one felt that the mummy, in the darkness beyond, might wel

think that his resurrection cal had come. One almost expected him to rise, like the dead

knights of Kildare in the Irish legend, and to ask, "Is it time?" for the three thousand years

which his religion had told him was the duration of his life in the tomb was already long past.

Meanwhile we turned our attention to the objects which stood in the passage, having been

placed there at the time of the funeral, owing to the lack of room in the burial-chamber. Here

a vase, rising upon a delicately shaped stand, attracted the eye by its beauty of form; and here

a bedstead caused us to exclaim at its modern appearance. A palm-leaf fan, used by the

ancient Egyptians to keep the flies off their wines and unguents, stood near a now empty jar;

and near by a basket of dried-up fruit was to be seen. This dried fruit gave the impression that

the tomb was perhaps a few months old, but there was nothing else to be seen which

suggested that the objects were even as much as a year old. It was almost impossible to

believe, and quite impossible to realise, that we were standing where no man had stood for

wel over three thousand years; and that we were actualy breathing the air which had

remained sealed in the passage since the ancient priests had closed the entrance thirteen

hundred years before Christ.

Before we could proceed farther, many flashlight photographs had to be taken, and drawings [180]

made of the doorway; and after this a panel of the woodwork had to be removed with a fret-

saw in order that the lock and seal might not be damaged. A