CHAPTER XXII.

Wherein Captain Galligasken sums up the magnificent Results of the Capture of Vicksburg, and starts with the illustrious Soldier for Chattanooga, after his Appointment to the Command of the combined Armies of the Tennessee, the Cumberland, and the Ohio.

Vicksburg had fallen! The nation was thrilled by the news. Grant's name rang throughout the land. The loyal people blessed him for the mighty deed he had done. The news flashed through the country, kindling up a joyous excitement, such as had not been known since the commencement of the war. The boasted stronghold of the rebels, the veritable Gibraltar of the West, had crumbled and fallen. Possibilities became facts. The decline of the Southern Confederacy had commenced.

Vicksburg had fallen! The news seemed too good to be true, and the waiting patriots of the nation trembled lest the vision of peace which it foreshadowed should be dissolved; but the telegraph flashed full confirmation, and every loyal heart beat firmer and truer than ever before.

Vicksburg had fallen! While the nation raised a pæan of grateful thanksgiving for the victory, and hailed Grant as the mightiest man of the Rebellion, the victorious general seemed hardly to be elated by his brilliant success, or to be conscious that he had achieved anything worthy of note. He smoked his cigar, calm and unmoved by the tempest of applause which began to reach him from the far North. It was hard to tell which was the more amazing—the magnitude of the victory or the modesty of the victor.

On the 4th of July—hallowed anew by this crowning victory—the rebel army marched out of the works it had so bravely defended, stacked their arms, and laid down their colors, returning prisoners of war. Thirty-one thousand six hundred men were surrendered to Grant, including two thousand one hundred and fifty-three officers, fifteen of whom were generals. One hundred and seventy-two cannons were captured with the place. It was the largest capture of men and guns ever made, not only in this war, but in the history of the world. Ulm surrendered to Napoleon, with thirty thousand men and sixty guns; but this event transcended the capitulation of Ulm, which Alison declares was a spectacle unparalleled in modern warfare; more men, and nearly three times as many guns, were taken at Vicksburg.

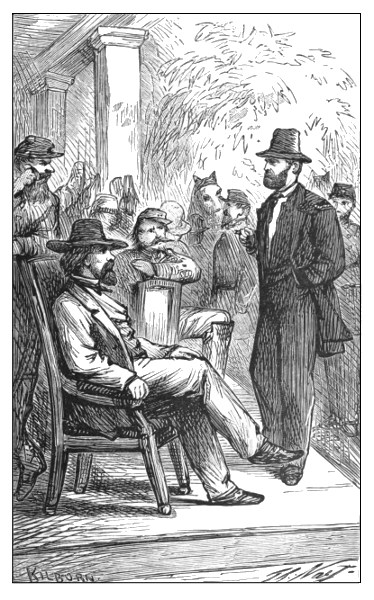

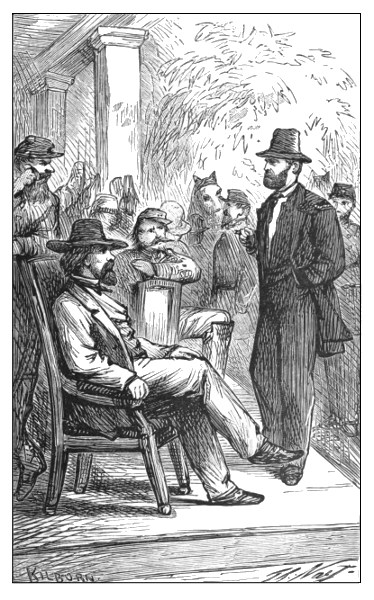

Grant and his staff, at the head of Logan's division, rode into the city, where the rebel soldiers gazed curiously at their conqueror, but manifested no disrespect; wherein they exhibited a more chivalrous spirit than did their officers. The general rode to the headquarters where the principal rebel officers were assembled. No one extended to him any act of courtesy, or behaved with even common decency. As no one came out to receive him, he dismounted, and walked up to the porch where Pemberton and his high-toned generals sat. They saluted him coldly, but no one proffered him a chair. By the grace of Grant they wore their swords; but not even this fact spurred them up to the simplest act of courtesy.

Pemberton himself was as crabbed and sour as a boor whose hen-coop had been robbed. His manner was morose and ungentlemanly, and his speech cold and curt. At last one of the party, with higher notions of chivalry than his companions, brought a chair for Grant. The day was hot and dusty, and the general asked for a glass of water. He was rudely informed that he could find water in the house. He entered, and searched the premises till a negro appeared, who supplied his want. Returning to the porch, he found his seat had been taken; and, during the rest of the interview, which lasted half an hour, he remained standing, in the company of these conquered rebels, who kept their seats in his presence!

In the light of this remarkable interview, I am inclined to believe that my friend Pollard, who denounces Pemberton as an imbecile, was more than half right in his estimate of the man; for no decent person, under such circumstances, would have been guilty of such flagrant discourtesy, as ridiculous as it was gross.

Grant was a Christian. He did not even resent this incivility. "If thine enemy hunger, feed him." Grant did so, literally; for at this interview Pemberton requested him to supply his garrison with rations. He did not say, "Let the dead bury their dead," as less magnanimous men than he might have done, after the contemptuous impoliteness of the rebels. Grant immediately consented; but probably there was not "chivalry" enough left in the bantam general to feel the heat of the "coals of fire upon his head."

Grant and Pemberton in Vicksburg.—.

Grant notified Banks, at Port Hudson, of the capture of Vicksburg, and offered to send him an army corps of "as good troops as ever trod American soil; no better are found on any other." Four days after the surrender, Port Hudson followed the example of Vicksburg. This event virtually completed the conquest of treason in the West. The Father of Waters rolled "unvexed to the sea," in the expressive language of President Lincoln. To sum up the results, in the words of Pollard, who is not particularly amiable at this point of his struggles through "The Lost Cause,"—"It was the loss of one of the largest armies which the Confederates had in the field; the decisive event of the Mississippi Valley; and the severance of the Southern Confederacy."

Proudly would I linger over this auspicious event; but the illustrious soldier had done his work, and the deed speaks for itself. His name was written in the annals of his country, never more to be effaced, even if he added not another laurel to his wreath of glory. He had practically ended the war on the Mississippi. On the day before, the great battle of Gettysburg culminated in victory, and the army of Lee was driven, shattered and weakened, from Pennsylvania. The tidings of these two great events spread through the land together, and created universal joy. Almost for the first time in two years, the loyal cause looked really hopeful. The Rebellion had been struck heavily in the East and in the West.

President Lincoln manifested his high appreciation of the conduct of Grant in the following characteristic letter:—

"Executive Mansion, Washington, July 13, 1863.

"Major General Grant.

"My dear General: I do not remember that you and I ever met personally. I write this now as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done the country. I wish to say a word further. When you first reached the vicinity of Vicksburg, I thought you should do what you finally did—march the troops across the neck, run the batteries with the transports, and thus go below; and I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition and the like could succeed. When you got below, and took Port Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join General Banks; and when you turned northward, east of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right and I was wrong.

A. Lincoln."

Halleck was almost as magnanimous as the president, and sent Grant a very handsome letter of congratulation.

For the brilliant campaign of Vicksburg, Grant was made a major-general in the regular army. He promptly recommended Sherman and McPherson for promotion to the rank of brigadier-general in the regular army, setting forth, in solid, compact arguments, the merits of these distinguished generals. These promotions were promptly made, as well as others which Grant suggested.

Sherman was sent out with a strong force to drive Johnston from the state, which he did most effectually, capturing Jackson a second time in his operations. On his return, the army of the Mississippi was broken up, and sent to Banks, Schofield, and Burnside. But Grant had no opportunity to rest upon his laurels; indeed, he wanted none. He gave his attention to the multiplicity of topics imposed upon him by the needs of his department. He threw all the weight of his position and influence into the task of raising and organizing negro troops. It was his intention to use them to garrison the posts on the river, believing that they would make good heavy artillerists.

He was among the first to acknowledge the value of this class of troops, and to award to them the praise which their valor in the field merited. He went farther than this; for he proposed to protect them from the operation of the savage policy of the rebels in regard to them. He intimated to General Dick Taylor that if he hung black soldiers he should retaliate; but the rebel general repudiated any such policy.

He discussed the question of trade with the enemy with Secretary Chase, and defended his views in opposition to it with dignity and ability. The duties of his department required a degree of statesmanship in their handling which he was found to possess; and the affairs of his jurisdiction were skilfully and prudently administered.

Previous to the separation of the grand army which had achieved the conquest of Vicksburg, Grant had proposed, and even urged, an expedition for the capture of Mobile by the way of Lake Pontchartrain. But the general-in-chief deemed it best to "clean up" the territory which had been conquered, by driving out the rebel forces from Western Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri. The president declared that the enterprise was "tempting," but recent events in Mexico rendered him desirous of establishing the national authority in Texas, so that no foreign foe could secure a foothold there; and he left the project for Halleck to dispose of. Grant felt that the Union was losing a splendid opportunity, for he had no doubt that a blow struck by the Vicksburg veterans at Mobile, before the rebels recovered from the shock of present disasters, would be entirely successful. He had the force, and only desired a couple of gunboats to cover his landing. Probably, if he had been permitted to undertake the venture, he would have succeeded, and the war would have been curtailed at least one year. Judging from analogy, and from the skill and spirit of the man, I am confident he would have make a success of it. I cannot conceive of such a thing as Grant's failing in anything. He might have been temporarily checked and turned back—once, twice, thrice; but he was absolutely sure to carry his point in the end. "Mr. Grant was a very obstinate man," as his good lady remarked.

While Sherman was driving Johnston out of Mississippi, Grant sent supplies of food and medicine to the enemy's sick at Raymond. If any man ever demonstrated the true spirit of Christianity, though without any display, Grant did so in his treatment of his own and his country's enemies.

The Thirteenth Corps had been sent down to assist in the expedition up the Red River and into Texas. Grant was anxious to see Banks, in order to arrange a plan by which he might coöperate with him, and he went to New Orleans. While there he was severely injured by being thrown from his horse at a review. The animal was a strange one to him, and was frightened by a locomotive, and rushing against a vehicle, dragged his rider off. He was confined to his bed, and compelled to lie "flat on his back" for twenty days. As soon as he was able to be moved, he returned to Vicksburg, but was obliged to keep his bed until the latter part of September, though he attended to all the business of his department.

During the summer Rosecrans had been operating in Tennessee and Northern Georgia, and had obtained possession of Chattanooga—the most important position between Richmond and the Mississippi. Bragg was manœuvring to cut him off from Nashville, his base of supplies. Grant started large reënforcements, including Sherman's command, to the threatened point. On the 20th of September, Rosecrans was defeated, before any of Grant's army reached him, in the heavy battle of Chickamauga, and compelled to retire to Chattanooga. His army was saved only by the address and bravery of General Thomas, who held his position in the face of an immensely superior force. A delay of ten days in the delivery of Halleck's order to Grant prevented the latter from sending troops in season to be of service.

Early in October Grant was directed, as soon as he was in condition to take the field,—for he was then able to move only on crutches,—to repair to Cairo, and report by telegraph. The order reached him at Columbus, and the next day, feeble as he was, he started for the point indicated, with his staff and headquarters. On his arrival he was instructed to meet an officer of the War Department in Louisville, Kentucky, to receive further orders. He started immediately by railroad, but at Indianapolis he met the secretary of war himself—Mr. Stanton.

A new command, called forth by the emergency, had been created for General Grant—"The military division of the Mississippi," including all the territory south of the Ohio between the Alleghanies and the Mississippi, with the exception of that occupied by Banks. It comprised, besides his own department of the Tennessee, those of the Cumberland, under Rosecrans, and the Ohio, under Burnside, all of which were now placed under his command. Grant had suggested this step a year before, in order to insure harmonious operations.

The secretary of war also carried two other orders with him, one continuing Rosecrans in his command of the army of the Cumberland, and the other removing him, and putting General Thomas in his place. Grant was permitted to make his choice between the two, and without hesitation he preferred the latter. Mr. Stanton accompanied the commander of the new division to Louisville, where it was rumored that Rosecrans was actually preparing to abandon Chattanooga, so closely was he pressed by the rebels, and harassed by the cutting off of his supplies. Grant, by order of the secretary, immediately assumed his command, telegraphing his order to Rosecrans, and assigning Thomas to the army of the Cumberland. He immediately took measures to prevent the apprehended calamity, desiring Thomas to hold Chattanooga at all hazards. The hero who had saved the entire army at Chickamauga replied at once in those memorable words which have been so often quoted, "I will hold the town till we starve."

East Tennessee, that home of the tried and trusty patriots, who had been so long neglected, and who had suffered untold misery, had been occupied by the national troops, and was now held by Burnside. Its safety depended upon the operations in progress at Chattanooga, which was the key-point of the system of railroads radiating to the east and south. It was absolutely necessary for the success of the national arms to hold this place, not only on account of its immense strategic importance, but because nearly all the people of the mountain region in which it is situated were loyal.

When Vicksburg fell, Bragg had been strengthened by the arrival of the troops which had been operating under Johnston in Grant's rear. But Rosecrans had out-generaled Bragg by getting to the southward of him, and threatening his supplies, thus compelling him to abandon Chattanooga. Having been largely reënforced, the rebel general had beaten Rosecrans at Chickamauga, and driven him into Chattanooga, where he had fortified himself, with the intention of holding the position.

Three miles from the Tennessee was Missionary Ridge, a range of hills four hundred feet high, which Bragg made haste to occupy. West of the town was Lookout Mountain, twenty-two hundred feet high, and three miles distant. Under this mountain extended the Nashville Railroad, by which the national army received its supplies. Rosecrans deemed it necessary to abandon this commanding height, which Bragg instantly seized. Planting his batteries upon it, he effectually held the country around it, and entirely cut off all supplies for Chattanooga, except such as could be sent by the mountain passes over sixty miles of rugged roads. Bragg drew his lines around the place from the river above to the river below.

Rosecrans's situation became desperate, for it was practically impossible to supply his troops by the mountain roads. The army was put on half rations, and three thousand sick and wounded were dying for the want of proper nourishment and medicines. Fodder for the horses and mules could not be obtained, and ten thousand of them died. All the artillery horses were sent round through the mountains to Bridgeport, but one third of them perished on the way. In case of retreat, it would be necessary to abandon the artillery, for the want of animals to draw it. To add to the perils of the situation, the ammunition was nearly exhausted. Short of clothing, short of tents, short of food, the condition of the army was deplorable in the extreme. Heavy rains deluged the earth, and the sufferings of the men were intense. It is not to be wondered at that Rosecrans was prepared to resort to so mild an expedient as abandoning the place. Bragg was waiting for starvation, cold, and intense suffering to fight his battle for him. He was unwilling to sacrifice a soldier in an assault, when Chattanooga was sure to fall under the weight of its own miseries. Only in Andersonville and on Belle Island were the sufferings of the troops surpassed.

Such was the terrible condition of the army of the Cumberland when Grant started for the field of action.