CHAPTER XXIII.

Wherein Captain Galligasken details the Means by which the illustrious Soldier relieved the Army of the Cumberland, and traces his Career to the glorious Victory of Chattanooga.

The stoutest heart would have been appalled at the situation in and around Chattanooga. Rosecrans had failed, and the army of the Cumberland was "bottled up" in the town. Grant, still feeble, and unable to move without his crutches, was ordered to extricate the force from its desperate dilemma; and not only to do this, but to save the place itself. One less resolute than he, or equally resolute, but less patriotic and devoted to the loyal cause, might well have exclaimed, "I pray thee have me excused!" Disabled as he was, he might have pointed to his crutches, and let them speak for him. They were not only a good excuse, but a good reason for not going upon such a perilous errand.

Could he have been borne at the head of the victorious veterans of Vicksburg, and gone into the beleaguered and starved town to the musical tramp of a large army, it would have looked more hopeful. But this could not be. Sherman had been started from Memphis with a heavy force—the army of the Tennessee—to assist Rosecrans, and he was still struggling through the country, beset with trials and difficulties. Not with this faithful friend and this tried army could the crippled general march into Chattanooga.

On the 20th of October, Grant started with only his staff for the imperilled point, and arrived at Nashville the same night. Even on his route, invalid as he was, he worked at the solution of the problem which had been given him to solve. He telegraphed to Burnside, foreshadowing his plans, and directing the operations of his subordinate. He requested Admiral Porter to send gunboats up the Tennessee to insure Sherman's safety, and to facilitate the passage of his supplies. To Thomas, in Chattanooga, he suggested the opening of the road to Bridgeport. Without having visited the scene of operations, he knew all about it, and was ready to grapple with the mighty difficulty.

At Bridgeport, on the Tennessee, the general and his party took horses for Chattanooga. The roads were rifted and torn up by the deluge of rains which had poured down the mountain sides. Here and there the highway was but a narrow shelf on the steep mountain side, and the region was strewed with the wrecks of wagons, and the bodies of animals which had died on the route, or had been killed by being precipitated over the steep bluffs. At many points the roads were not in condition to admit of the passage of the party on horseback, and the animals were led over them; Grant, still a cripple, was borne in the arms of his companions.

Thus journeyed the great commander to the front, issuing his mandates for the government of these armies, ordering up supplies, and indicating the means of forwarding them. I say, enthusiastically, that the spectacle of a man in his crippled condition, undertaking such an herculean task, controlling the minutest details, and moving forward confidently to retrieve the most desperate situation which the whole war presented, is sublime. I cannot fully express my admiration with any other term.

It was dark, and the rain poured in torrents, when Grant reached Chattanooga. If he had not quailed at the prospect before, well might he then. The rebels, in greatly superior force, hemmed in the town, save on the north, where the ragged mountain steeps beyond the river were almost as forbidding as the closed-up lines of the enemy. The officers and men were sad, weary, and almost hopeless. Their supplies were nearly exhausted, and there was little hope either in a battle or a retreat. To this scene of his future labors, the disabled and worn-out commander was introduced on his arrival. He did not despair; he was the messenger of hope and ultimate triumph.

On the night of his arrival he requested that Sherman should be placed in command of the army of the Tennessee, and his wish was granted. Hooker's command from the army of the Potomac had been sent down to act with the army of the Cumberland, and was now at Bridgeport. The question of supplies was the first which engaged Grant's attention. Except the town of Chattanooga, the rebels held all the country south of the Tennessee, and frequently invaded the northern shore in cavalry raids, cutting off the Union supplies. A pontoon bridge was stretched across the river at Brown's Ferry, the boats, each carrying thirty men, being silently floated down the river unobserved by the rebel pickets. The operation was conducted in the night, and, being a complete success, a footing was gained on the south bank of the river below the town.

The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad crossed the Tennessee at Bridgeport, where Hooker, with the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps, was located, and came up to Chattanooga through Lookout Valley, on the south side of the stream, which, being in the hands of the enemy, had cut off the supplies. Hooker was ordered to cross the river, and follow the railroad up to the valley. At Wauhatchie he encountered the rebels, but drove them before him, and reached a point within a mile of the new pontoon bridge on the night of the 28th of October. He was fiercely attacked by Longstreet, but successfully repelled the assault, and Lookout Valley was virtually captured. By this movement a direct road to Bridgeport, to which the railroad from Nashville was in working order, was opened in five days after the arrival of Grant.

Only a week before, Jeff. Davis himself had stood upon the summit of Lookout Mountain, and gazed down upon the Union army shut up in Chattanooga, absolutely sure that in a brief period, without striking a blow, it must surrender to Bragg. The tables were suddenly turned by the matchless skill of Grant. The ammunition and stores poured in upon the desponding army, now reënforced by two corps, and hope and joy supplanted fear and despair. The hungry men were once more fed on full rations, horses were promptly brought up, and the army of the Cumberland was ready to become the assailants again. The rebels were confounded by the sudden change in the situation before them.

Grant arranged the details of conveying supplies to Burnside, five hundred miles up the Cumberland, and thence by wagons, one hundred farther, to Knoxville. He repeatedly urged upon this gallant soldier the imperative necessity of holding East Tennessee, though the government had some doubts in regard to his ability to do so. Grant was only waiting for the arrival of Sherman, with the army of Tennessee, to attack the enemy; but until then he could do nothing. Bragg, to better his own prospects, sent Longstreet, with twenty thousand men and eighty guns, into East Tennessee, and great anxiety was manifested for the safety of Burnside's command. The rebels held the railroad from Chattanooga nearly up to Knoxville, and Grant's force was insufficient to enable him to render any direct aid. Burnside was sorely pressed by the foe, but maintained himself nobly. Grant frequently sent him hopeful messages, and assured himself that East Tennessee would be held.

On the night of the 14th of November, Sherman reported in Chattanooga to his commander. The plan of the great battle which was to relieve Burnside, and compel the enemy "to take to the mountain passes by every available road," had already been formed. The operations were delayed by savage storms, which raised the river, and damaged the pontoon bridges, employed to their utmost capacity in crossing Sherman's troops; but on the 23d the line was formed for the assault.

On the 20th, Grant had received a letter from Bragg, suggesting that if there were any non-combatants in Chattanooga, prudence would suggest their early withdrawal; but this was only a trick, which did not deceive Grant; and two days later he obtained information that Bragg was preparing to evacuate his position on Missionary Ridge.

Thomas's line, composed of the army of the Cumberland, was drawn up in front of the town. Just before it were the rebel pickets in close proximity to those of the national army; indeed, both drew water from a creek which was the dividing line between them. Grant occasionally rode out to this stream to observe the position of the enemy. One day he saw a party of soldiers drawing water. As they wore blue coats, he supposed they belonged to his own force, and he asked them to whose command they belonged.

"To Longstreet's corps," replied one of them.

"What are you doing in those coats then?" demanded Grant, unmoved, when almost any other general officer would have decamped in a hurry, for fear an accident might happen.

"O, all our corps wear blue!" added the rebel spokesman.

Grant had forgotten this fact, and the rebels scrambled up their own side of the stream, little suspicious that they had been conversing with the commander of the united national armies.

The guns in battery along the line opened fire, and the enemy's works on the long range of hills, replied to the vigorous salute. The line of Thomas's army moved forward, and the grand spectacle commenced. It was a magnificent sight, and we who beheld it can never forget the gleam of those twenty thousand bayonets, as the column pressed steadily on. The enemy believed it was only a holiday pageant, and their pickets leaned on their muskets, and watched the brilliant movement. A few shots from the skirmishers scattered these spectators, and the battle commenced. The army of the Cumberland was intent upon wiping out the stain of Chickamauga, and charged impetuously upon the line of rifle-pits before them, capturing them, and carrying Orchard Knoll, a hill of considerable importance for future operations. The enemy had been driven back a mile, and the nationals halted, and fortified the ground they had captured.

On the right was Hooker, occupying Lookout Valley, above which frowned the heights of Lookout Mountain, bristling with rebel cannon. On the creek, in the middle of the valley, extended the line of Confederate pickets; but there was no approach to the mountain on this side. Hooker sent a column round its base to a road which conducted, by a zigzag route, to the summit. The enemy's pickets were captured, and Lookout Creek bridged.

Hooker's troops fought with the utmost bravery, and demonstrated that Eastern soldiers, when well led, were fully the equals of those of the West. They swept everything before them in the fierce struggle that followed. The Union batteries opened, and the rebels replied from the steeps of the mountain, drawing down, as it seemed, the thunder and the lightning from the clouds above, till the hills trembled in the commotion. The column under General Geary, passing through a piece of woods, reached the road which led to the heights above. It was a steep path, and every accessible place was occupied by troops and guns for its defence. But the column dashed up the precipitous slopes, beating down all opposition, capturing guns and men on their way. Onward and upward, in the literal sense of the words, they swept, penetrating the clouds, which soon hid them from the view of those below. Hooker's battle in the clouds was a complete success, and Lookout Mountain was captured. Two thousand prisoners were taken, and the victors in this remarkable contest rested from their labors on the summit. They had "gone up," in the highest sense of the phrase, and the rebels also, in another sense.

Hooker on the right, and Thomas in the centre, had carried out their portion in the grand programme of the battle; so also had Sherman on the left. The enemy had been deceived into the belief that his whole force was to operate in the vicinity of Lookout Mountain, while it was cautiously moved to a concealed position up the river, and in the rear of the town. One hundred and sixteen pontoons were conveyed over the land, and launched in the North Chickamauga Creek, five miles above the mouth of a stream with the same name on the south side of the river. On the night before the grand battle, these boats were loaded with men, and floated down the creek and the Tennessee, until they reached a point immediately below South Chickamauga Creek, where the bridge was to be built over the river for the passage of Sherman's army. All the citizens in the vicinity had been put under guard, so that the enemy might not learn what was in progress.

The boats landed on the south side of the river, the troops disembarked, the enemy's outpost was captured, and a position secured for the beginning of the pontoon bridge. Troops were crossed in boats continually. At noon the bridge was completed; the army crossed, and Sherman commenced the march upon the enemy's positions on the left. The troops were pushed up the hill, and soon gained a commanding eminence, which was immediately fortified, and guns were dragged up for its defence. The rebels opened with artillery upon the unexpected foe, but Sherman was already in possession. A sharp engagement ensued with the infantry, but the enemy soon withdrew, and the northern portion of Missionary Ridge was carried.

The morning of the next day dawned clear and cold, revealing the two armies prepared for the final struggle, in which one was eager to engage, and which the other could not avoid. The rebels were still strongly intrenched on Missionary Ridge, whose summit had an extent of seven miles. Grant took position with his staff on Orchard Knoll, where he could command a view of the entire battle-field. Plainly to be seen on the heights above him were the headquarters of the rebel general.

In accordance with his orders, Sherman began the attack on the left, and closely pressed the Confederate position. Bragg saw his lines yielding, and sent reenforcements from the centre, precisely as Grant intended he should do. Sherman secured a position at the first onslaught, and the battle around him was waged with the most tremendous fury by both sides; but no further advantage was gained. On the right, Hooker was working his way around the rebel flank, and Grant, having been assured that he was in position to do his part of the work, directed Thomas to move forward in the centre, the rebel general having weakened this portion of his line to strengthen his right flank.

The four divisions of the army of the Cumberland, one of which was commanded by Sheridan, made a charge, captured the enemy's rifle-pits at the foot of the Ridge, and took one thousand prisoners. Thirty guns immediately opened upon them with grape and canister, cutting them down in awful slaughter; but it delayed not their march. Steadily they pushed their way towards the crest of the ridge, and, halfway up, encountered another line of rifle-pits, which they charged upon and carried with the same impetuous fury which had marked their first assault.

Grant and Thomas, on the knoll below, watched the fearful fighting, as the column mounted the hill. A portion of it was momentarily checked and turned by the savage fire poured in upon it. Thomas turned to Grant and said, with some hesitation, which revealed the emotion he struggled to conceal in the presence of his chief,—

"General, I—I'm—I'm—afraid they won't get up."

Grant looked steadfastly at the column, waiting half a minute before he made any reply; then, coolly taking the cigar he was smoking from his mouth, he brushed away the ashes before he answered,—

"O, give them time, general," and quietly returned the cigar to his mouth.

They only wanted a few moments more, and gathering up their energies, the men pressed forward with redoubled zeal, and gained the summit of the Ridge. With furious cheers they threw themselves upon the rebel works, and carried them almost instantly. The foe was overwhelmed in his strongest position, which, as Bragg said himself, "a line of skirmishers ought to have maintained against any assaulting force." Whole regiments threw down their arms, and others fled in hot haste down the eastern slope. The artillery was captured, and turned upon other portions of the rebel position. The Confederate line was sundered, and the enemy were thoroughly beaten in forty-five minutes after the order to charge had been given on the plain below.

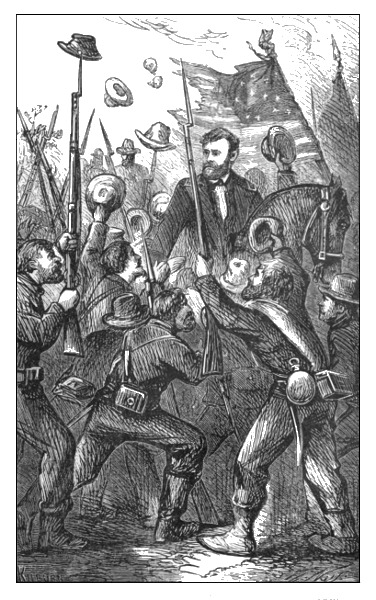

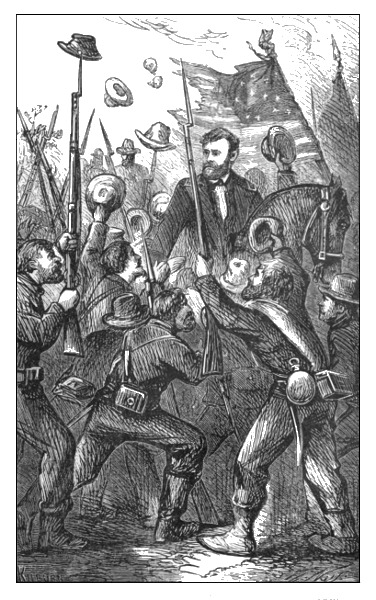

In the moment of victory Grant appeared upon the Ridge, and, passing along with his head uncovered, received the unanimous applause of the soldiers. They were in a transport of ecstasy over the victory they had won, and gathered around him with volleys of cheers, grasping his hands, and embracing his legs. I wonder not at their enthusiasm, for these men were of the army of the Cumberland, who had been "bottled up" in Chattanooga, to starve and die: and while they hailed the victorious general as the author of the triumph they had achieved, they also hailed him as their own deliverer. He coolly but not insensibly received their grateful plaudits. Without pausing to indulge in any self-glorification, he made the dispositions to complete the victory and pursue the fleeing host of rebels.

Grant and the Soldiers at Missionary Ridge.

The victory was thorough and entire. All the rebel positions had been captured. Forty guns, seven thousand small arms, and six thousand prisoners were taken—the heaviest spoils of any battle fought in the field during the war. The loss of the Union army, in killed, wounded, and missing, was fifty-six hundred and sixteen. The rebel loss in killed and wounded was much less, for they fought with all the advantages of a secure position.

Grant had sixty thousand men, Bragg forty-five thousand; but the elevated situation, and the elaborate intrenchments in which they fought, ought to have rendered them equivalent to twice that force, as the rebel general practically admitted.

The pursuit of the enemy was vigorously followed up, railroads were destroyed, and immense quantities of stores and rations captured, which the rebels could ill afford to lose. Bragg had been entirely confident of his ability to hold his position, and at one time, just before Thomas's troops reached the crest of the hill, he was congratulating his troops upon the victory they had won. While he was thus engaged, the army of the Cumberland broke through his line, and compelled him to run for his life.

During this fierce battle, Phil Sheridan first attracted the attention of Grant, by his bold and daring conduct, no less than by his skilful movements; though the great cavalryman did not know of his good fortune for months. He had simply been "spotted" for future use.

The battle of Chattanooga was ended in a glorious victory for the Union, and one of the saddest defeats of the war to the Confederates—one which put my friend Pollard into "fits," causing him to declare that "the day was shamefully lost."