IX AUGUST

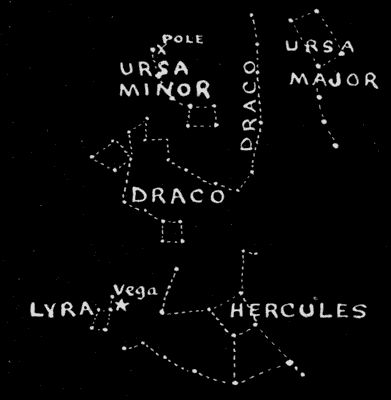

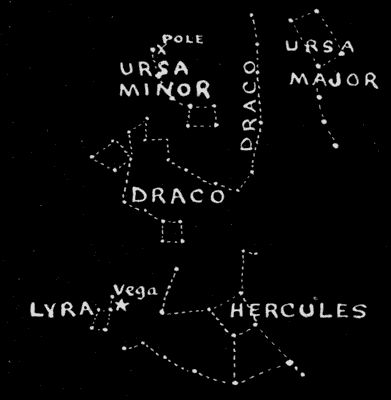

It was one of the twelve labors of Hercules, the hero of Grecian mythology, to vanquish the dragon that guarded the golden apples in the garden of the Hesperides. Among the constellations for July we found the large group of stars that represents the hero himself, and this month we find just to the north of Hercules the head of Draco, The Dragon. The foot of the hero rests upon the dragon's head, which is outlined by a group of four fairly bright stars forming a quadrilateral or four-sided figure. The brightest star in this group passes in its daily circuit of the pole almost through the zenith of London. That is, as it crosses the meridian of London, it is almost exactly overhead. From the head of Draco, the creature's body can be traced in a long line of stars curving first eastward, then northward, toward the pole-star to a point above Hercules, where it bends sharply westward. The body of the monster lies chiefly between its head and the bowl of the Little Dipper. The tail extends in a long line of faint stars midway between the two Dippers, or the constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the tip of the tail lying on the line connecting the Pointers of the Big Dipper with the pole-star Polaris.

Draco, as well as Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, is a circumpolar constellation in our latitude; that is, it makes its circuit of the pole without at any time dipping below the horizon in latitudes north of 40°. It is, therefore, visible at all hours of the night in mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, but is seen to the best advantage during the early evening hours in the summer months. There are no remarkable stars in this constellation with the exception of Alpha, which lies halfway between the bowl of the Little Dipper and Mizar, the star at the bend in the handle of the Big Dipper.

August—Draco and Lyra

About four thousand seven hundred years ago, this star was the pole-star—lying even nearer to what was then the north pole of the heavens than Polaris does to the present position of the pole. The sun and moon exert a pull on the bulging equatorial regions of the earth, which tends to draw the plane of the earth's equator down into the plane of the ecliptic. This causes the "Precession of the Equinoxes" and at the same time a slow revolution of the earth's axis of rotation about the pole of the ecliptic. The north pole of the heavens as a result describes a circle about the pole of the ecliptic of radius 23½° in a period of 25,800 years.

Each bright star that lies near the circumference of this circle becomes in turn the pole-star sometime within this period. The star Alpha, in Draco, had its turn at being pole-star some forty-seven centuries ago. Polaris is now a little over a degree from the north pole of the heavens. During the next two centuries it will continue to approach the pole until it comes within a quarter of a degree of it, when its distance from the pole will begin to increase again. About twelve thousand years hence the magnificent Vega, whose acquaintance we will now make, will be the most brilliant and beautiful of all pole-stars.

Vega (Arabic for "Falling Eagle") is the resplendent, bluish-white, first-magnitude star that lies in the constellation of Lyra, The Lyre or Harp, a small, but important, constellation just east of Hercules and a little to the southeast of the head of Draco. Vega is almost exactly equal in brightness to Arcturus, the orange-colored star in Boötes, now lying west of the meridian in the early evening hours. It is also a near neighbor of the solar system, its light taking something like forty years to travel to the earth. Vega is carried nearly through the zenith of Washington and all places in the same latitude by the apparent daily rotation of the heavens. It is a star that we have no difficulty in recognizing, owing to the presence of two nearby stars that form, with it, a small equal-sided triangle with sides only two degrees in extent. If our own sun were at the distance of Vega, it would not appear as bright as one of these faint stars, so much more brilliant is this magnificent sun than our own. The two faint stars that follow so closely after Vega and form the little triangle with it are also of particular interest. Epsilon Lyræ, which is the northern one of these two stars, may be used as a test of keen eyesight. It is the finest example in the heavens of a quadruple star—that is, "a double-double star." A keen eye can just separate this star into two without a telescope, and with the aid of a telescope, each of the two splits up into two stars, making four stars in place of the one visible to the average eye. Zeta, the other of the two stars that form the little triangle with Vega, is also a fine double star. The star that lies almost in a straight line with Epsilon and Zeta and a short distance to the south of them is a very interesting variable star known as Beta Lyræ. Its brightness changes very considerably in a period of twelve days and twenty-two hours. This change of brightness is due to the presence of a companion star. The two stars are in mutual revolution, and their motion is viewed at such an angle from the earth that, in each revolution, one star is eclipsed by the other, producing a variation in the amount of light that reaches our eyes. By comparing this star from day to day with the star just a short distance to the southeast of it, which does not vary in brightness, we can observe for ourselves this change in the light of Beta Lyræ. There are a number of stars in the heavens that vary in brightness in the same manner as Beta Lyræ, and they are called eclipsing-variable stars.

On the line connecting Beta Lyræ with the star southeast of it and one-third of the distance from Beta to this star, lies the noted Ring Nebula in Lyra, which is a beautiful object even in a small telescope. It consists of a ring of luminous gas surrounding a central star. The star shines with a brilliant, bluish-white light and is visible only in powerful telescopes though it is easily photographed since it gives forth rays to which the photographic plate is particularly sensitive. In small telescopes the central part of this nebula appears dark but with a powerful telescope a faint light may be seen even in the central portion of the nebula. This is one of the most interesting and beautiful telescopic objects in the heavens.

It is in the general direction of the constellation of Lyra that our solar system is speeding at the rate of more than a million miles a day. This point toward which we are moving at such tremendous speed lies a little to the southwest of Vega, on the border between the constellations of Lyra and Hercules, and is spoken of as The Apex of the Sun's Way.

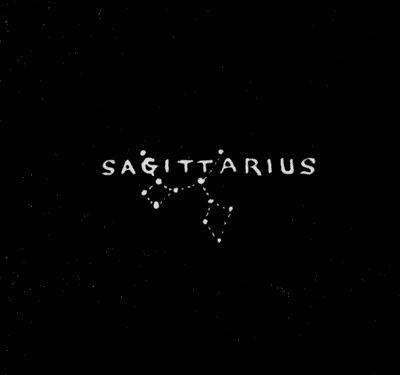

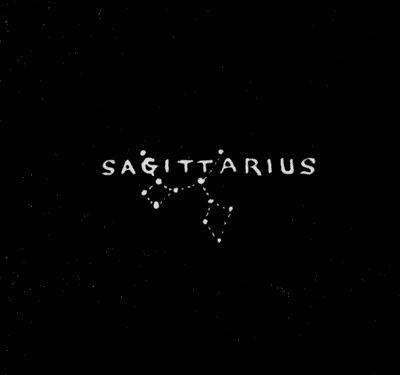

August—Sagittarius

In the southern sky we have this month the constellation of Sagittarius, The Archer, which is just to the east of Scorpio and a considerable distance south of Lyra. It can be recognized by its peculiar form, which is that of a short-handled milk dipper, with the bowl turned toward the south and a trail of bright stars running from the end of the handle toward the southwest. This is one of the zodiacal groups which contain no first-magnitude stars, but a number of the second and third magnitude. It is crossed by the Milky Way, which is very wonderful in its structure at this point. Some astronomers believe that here—among the star-clouds and mists of nebulous light which are intermingled with dark lanes and holes, in reality dark nebulæ—lies the center of the vast system of stars and nebulæ in which our entire solar system is but the merest speck. Some of the grandest views through the telescope are also to be obtained in this beautiful constellation of Sagittarius, which is so far south that it is seen to better advantage in the tropics than in the mid-latitudes of the northern hemispheres.