X SEPTEMBER

One of the most beautiful constellations of the northern hemisphere is Cygnus, The Swan, which is in the zenith in mid-latitudes about nine o'clock in the evening the middle of September. It lies directly in the path of the Milky Way which stretches diagonally across the heavens from the northeast to the southwest at this time. In Cygnus, the Milky Way divides into two branches, one passing through Ophiuchus and Serpens to Scorpio, and the other through Sagitta and Aquila to Sagittarius, to meet again in the southern constellation of Ara, just south of Scorpio and Sagittarius. On clear, dark evenings, when there is no moonlight, this long, dark rift in the Milky Way can be seen very clearly. In Cygnus, as in Ophiuchus, Scorpio, and Sagittarius we find wonderful star-clouds, consisting of numberless stars so distant from us and, therefore, so faint that they do not appear as distinct points of light except in the greatest telescopes. It is the combined light from these numberless stars that cannot be seen separately that produces the impression of stars massed in clouds of nebulous light and gives to this girdle of the heavens its name of the Milky Way. In Cygnus, as in a number of other constellations of both hemispheres, the Milky Way is crossed by dark rifts and bars and is very complicated in its structure. It is in Cygnus, also, that one may see with the aid of powerful telescopes the vast, irregular, luminous nebulæ, that are like great clouds of fiery mist. These nebulæ are of enormous extent, for they cover space that could be occupied by hundreds of stars.

September—Cygnus

Cygnus is a constellation that is filled with the wonders and mysteries of space and that abounds in beautiful objects of varied kinds. It is a region one never tires of exploring with the telescope. The principal stars in Cygnus form the well-known Northern Cross, with the beautiful, white, first-magnitude star Deneb, or Arided, as it is sometimes called, at the top of the cross, and Albireo, the orange-and-blue double star at the foot. Albireo, among all the pairs of contrasting hues, has the distinction of being considered the finest double star in the heavens for small telescopes. This star marks the head of The Swan, as well as the foot of the Northern Cross, and Deneb marks the tail of The Swan. A short distance to the southeast of Deneb, on the right wing of The Swan, is a famous little star, 61 Cygni, barely visible to the naked eye and forming a little triangle with two brighter stars to the east. This star has the distinction of being the first one to have its distance from the solar system determined. The famous mathematician and astronomer Bessel accomplished this difficult feat in the year 1838. Since that day, the distances of many stars have been found by various methods, but of all these stars only four or five are known to be nearer to us than 61 Cygni. Its distance is about eight light-years, so its light takes about eight years to travel the distance that separates it from the solar system. As a result, we see it not as it is tonight, but as it was at the time when the light now entering our eyes first started on its journey eight years ago. 61 Cygni is also a double star, and the combined light of the two stars gives forth only one-tenth as much light as our own sun. Most of the brilliant first-magnitude stars give forth many times as much light as the sun; but among the fainter stars, we find some that appear faint because they are very distant, and some that are faint because they are dwarf stars and have little light to give forth. To the class of nearby, feebly-shining dwarf stars 61 Cygni belongs. Deneb, on the other hand, is one of the giant stars, and is at an immeasurably great distance from the solar system.

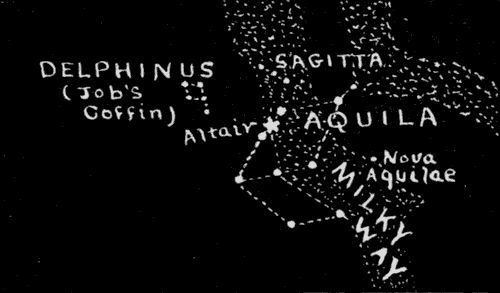

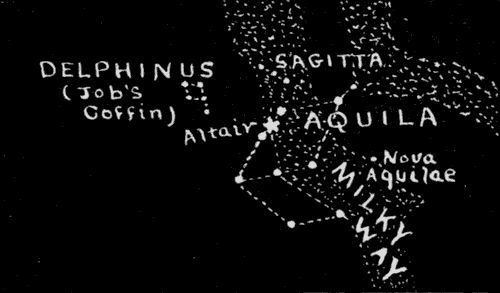

Just south of Cygnus in the eastern branch of the Milky Way lie Sagitta, The Arrow, and Aquila, The Eagle. Not far to the northeast of Aquila is the odd little constellation of Delphinus, The Dolphin, popularly referred to as Job's Coffin. There will be no difficulty in finding this small star-group, owing to its peculiar diamond-shaped configuration. Its five principal stars are of the fourth magnitude. It is in the constellation of Delphinus that the most distant known object in the heavens is located. This is the globular star cluster known only by its catalogue number of N.G.C. 7006. It is estimated to be at a distance of 220,000 light-years from the earth.

Sagitta, The Arrow, lies midway between Albireo and the brilliant Altair in Aquila. The point of the arrow is indicated by the star that is farthest east; and the feather, by the two faint stars to the west. Like Delphinus, this constellation is very small and contains no objects of particular interest.

Altair (Flying Eagle) is the brilliant white star of the first magnitude in Aquila and is attended by two fainter stars, one on either side, at nearly equal distances from it. These two stars serve readily to distinguish this star, all three stars being nearly in a straight line. Altair is one of the nearer stars, its distance from the earth being about sixteen light-years. It gives forth about ten times as much light as the sun.

September—Delphinus, Aquila and Sagitta

We cannot leave the constellation of Aquila without referring to the wonderful temporary star or nova, known as Nova Aquilæ No. 3 (because it was the third nova to appear in this constellation), which appeared in the position indicated on the chart upon the eighth of June, 1918. A few days previous to this date, there was in this position an extremely faint star, invisible to the naked eye and in small telescopes. This fact became known from later examinations of old photographs of this region that had been taken at the Harvard College Observatory, where the photographing of the heavens is carried on regularly for the purpose of having a record of celestial changes and happenings. Clouds prevented the obtaining of any photographs of this part of the heavens on the four nights preceding the eighth of June, but on this evening there shone in the place of the faint telescopic star, a wonderful temporary star, or nova, which was destined on the next evening to outshine all stars in the heavens, with the exception of the brightest of all, Sirius, which it closely rivaled in brilliancy at the height of its outburst. Within less than a week's time, this faint star in the Milky Way for some mysterious reason increased in brightness many thousandfold. Such outbursts have been recorded before, but on rare occasions, however. No star since the appearance of the nova known as Kepler's Star, in the year 1604, which at its greatest brilliancy rivaled Jupiter, shone with such splendor or attracted so much attention as Nova Aquilæ. In the year 1901, there appeared in the constellation of Perseus a star known as Nova Persei which at its brightest surpassed Vega, but its splendor was not as great as that of the wonderful nova of 1918.

It speaks well for the zeal and interest of amateur astronomers, as well as for their acquaintance with the stars, that Nova Persei was discovered by an amateur astronomer, Dr. Anderson, and that among the deluge of telephone calls and telegrams received at the Harvard College Observatory on the night of June 8th, announcing independent discoveries of the "new star," were many from non-professional astronomers.

Like all stars of this class, Nova Aquilæ No. 3 sank rapidly into oblivion. In a few weeks it was only a third-magnitude star; a few weeks more and it was invisible without a telescope. Many wonderful and interesting changes have been recorded in the appearance of this star, however, even after it became visible only in the telescope. Soon after its outburst it appeared to develop a nebulous envelope, as have other novas before it. It showed in addition many of the peculiarities of the nebulæ, though the central star remained visible as before the outburst.

Astronomers are still in doubt as to the cause of these outbursts, which certainly indicate celestial catastrophies of some form on a gigantic scale. All novas possess one characteristic in common—that of appearing exclusively in the Milky Way; and another characteristic is the development of a nebular envelope after the outburst of greatest brightness. In some cases temporary stars have been known to be variable in brightness for years before the great outburst. Such a star was Nova Aquila, for the examination of photographs of this region taken some years previous showed variations in its brightness for a period of thirty years at least.

Up to the beginning of this century only about thirty novas had been discovered. Since that date, thanks to the vigilance of the astronomers of today and to the aid of photography, more have been discovered than in all the preceding centuries. These outbursts of new stars appear to be not so rare as the earlier astronomers believed, though great outbursts as brilliant as that of Nova Aquila are very uncommon.