IV MARCH

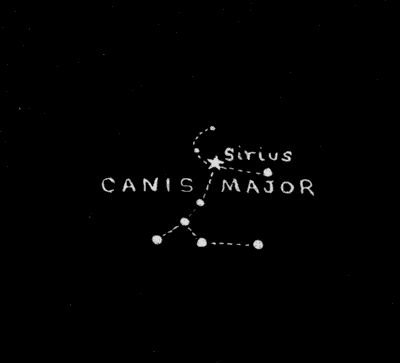

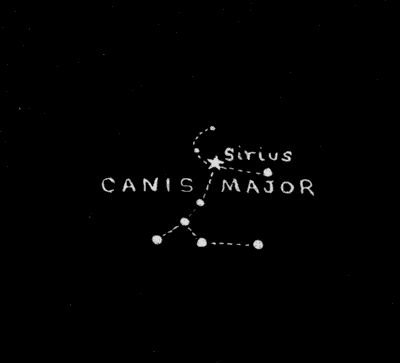

To the southeast of Orion and almost due south at eight o'clock in the evening on the first of March lies the constellation of Canis Major, The Greater Dog, containing Sirius, the Dog-star, which far surpasses all other stars in the heavens in brilliancy.

Sirius lies almost in line with the three stars that form the Belt of Orion. We shall not have the slightest difficulty in recognizing it, owing to its surpassing brilliancy as well as to the fact that it follows so closely upon the heels of Orion.

Sirius is the Greek for "scorching" or "sparkling," and the ancients attributed the scorching heat of summer to the fact that Sirius then rose with the sun. The torrid days of midsummer they called the "dog-days" for this reason, and we have retained the expression to the present time. Since Sirius was always associated with the discomforts of the torrid season, it did not have an enviable reputation among the Greeks. We find in Pope's translation of the Iliad this reference to Sirius:

"Terrific glory! for his burning breath

Taints the red air with fever, plagues, and death."

In Egypt, however, many temples were dedicated to the worship of Sirius, for the reason that some five thousand years ago it rose with the sun at the time of the summer solstice, which marks the beginning of summer, and heralded the approaching inundation of the Nile, which was an occasion for great rejoicing among the Egyptians. It was, therefore, called the Nile Star and regarded by them with the greatest reverence.

Sirius is an intensely white hydrogen star; but owing to its great brilliancy and to the fact that it does not attain a great height above the horizon in our latitudes, its rays are greatly refracted or broken up by the atmosphere, which is most dense near the horizon, and as a result, it twinkles or scintillates more noticeably than other stars and flashes the spectrum colors—chiefly red and green—like a true "diamond in the sky"—a magnificent object in the telescope.

Sirius is one of our nearest neighbors among the stars. Only two stars are known to be nearer to the solar system. Yet its light takes about eight and a half years to flash with lightning speed across the great intervening chasm. It is attended also by a very faint star that is so lost in the rays of its brilliant companion that it can only be found with the aid of a powerful telescope. The two stars are separated by a distance of 1,800,000,000 miles; that is they are about as far apart as Neptune and the sun. They swing slowly and majestically about a common center, called their center of gravity, in a period of about forty-nine years. So faint is the companion of Sirius that it is estimated that twenty thousand such stars would be needed to give forth as much light as Sirius. The two stars together, Sirius and its companion, give forth twenty-six times as much light as our own sun. They weigh only about three times as much, however. The companion of Sirius, in spite of its extreme faintness, weighs fully half as much as the brilliant star.

March—Canis Major

There are a number of bright stars in the constellation of Canis Major. A fairly bright star a little to the west of Sirius marks the uplifted paw of the dog, and to the southeast, in the tail and hind quarters, are several conspicuous stars of the second magnitude.

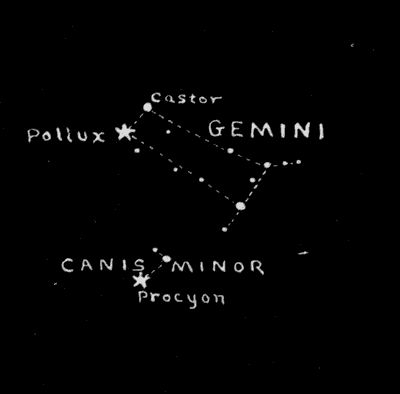

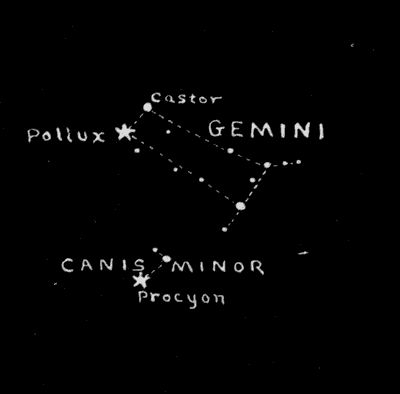

A little to the east and much farther to the north, we find Canis Minor, The Lesser Dog, containing the beautiful first-magnitude star Procyon, "Precursor of the Dog"—that is, of Sirius. Since Procyon is so much farther north than Sirius and very little to the east, we see its brilliant rays in the eastern sky some time before Sirius appears above the southeastern horizon, hence its name. Long after Sirius has disappeared from view beneath the western horizon in the late spring, Procyon may still be seen low in the western sky. Procyon, also is one of our nearer neighbors among the stars, being only about ten light-years distant from the solar system. Like Sirius, it is a double star with a much fainter companion, that by its attraction sways the motion of Procyon to such an extent that we should know of its existence, even if it were not visible, by the disturbances it produces in the motion of Procyon. The period of revolution of Procyon and its companion about a common center is about forty years, and the two stars combined weigh about a third more than our own sun and give forth six times as much light. Canis Minor contains only one other bright star, Beta, a short distance to the northwest of Procyon. Originally, the name Procyon was given to the entire constellation, but it was later used only with reference to the one star. Procyon, Sirius, and Betelgeuze in Orion form a huge equal-sided triangle that lies across the meridian at this time and is a most conspicuous configuration in the evening sky.

March—Gemini and Canis Minor

Directly south of the zenith we find Gemini, The Twins, one of the zodiacal constellations. It is in Gemini that the sun is to be found at the beginning of summer. The two bright stars Castor and Pollux mark the heads of the twins, and the two stars in the opposite corners of the four-sided figure shown in the chart mark their feet.

Castor and Pollux, according to the legend, were the twin brothers of Helen of Troy who went on the Argonautic expedition. When a storm overtook the vessel on its return voyage, Orpheus invoked the aid of Apollo, who caused two stars to shine above the heads of the twins, and the storm immediately ceased. It was for this reason that Castor and Pollux became the special deities of seamen, and it was customary to place their effigies upon the prows of vessels. The "By Jimini!" of today is but a corruption of the "By Gemini!" heard so frequently among the sailors of the ancient world.

The astronomical name for Castor, the fainter star, is Alpha Geminorum, meaning Alpha of Gemini. As it was customary to call the brightest star in a constellation by the first letter in the Greek alphabet, it is believed that Castor has decreased considerably in brightness since the days of the ancients, for it is now decidedly inferior to Pollux in brightness, which is called Beta Geminorum. Of the two stars, Castor is the more interesting because it is a double star that is readily separated into two stars with the aid of a small telescope. The two principal stars are known to be, in turn, extremely close double stars revolving almost in contact in periods of a few days. Where we see but one star with the unaided eye, there is, then a system of four suns, the two close pairs revolving slowly about a common center of gravity in a period of several centuries and at a great distance apart.

The star Pollux, which we can easily distinguish by its superior brightness, is the more southerly of the twin stars and lies due north of Procyon and about as far from Procyon as Procyon is from Sirius.

The appearance of Gemini on the meridian in the early evening and of the huge triangle, with its corners marked by the brilliants, Procyon, Sirius, and Betelgeuze, due south, with "Great Orion sloping slowly to the west," is as truly a sign of approaching spring as the gradual lengthening of the days, the appearance of crocuses and daffodils, and the first robin. It is only a few weeks later—as pictured by Tennyson in Maud—

"When the face of the night is fair on the dewy downs,

And the shining daffodil dies, and the Charioteer

And starry Gemini hang like glorious crowns

Over Orion's grave low down in the west."