V APRIL

In the early evening hours of April the western sky is still adorned with the brilliant jewels with which we became familiar on the clear frosty evenings of winter. Orion is now sinking fast to his rest beneath the western horizon. Beautiful, golden Capella in Auriga glows in the northwest. Sirius sparkles and scintillates, a magnificent diamond of the sky, just above the southwestern horizon, while Procyon in Canis Minor, The Lesser Dog, and Castor and Pollux, The Twins, in the constellation of Gemini, are still high in the western part of the heavens.

In the northeast and east may be seen the constellations that will be close to the meridian at this time next month. Ursa Major, The Greater Bear, with its familiar Big Dipper, is now in a favorable position for observation. The Sickle in Leo is high in the eastern sky, and Spica, the brilliant white diamond of the evening skies of spring, is low in the southeast in Virgo.

Near the meridian this month we find between Auriga and Ursa Major, and east of Gemini, the inconspicuous constellation of Lynx, which contains not a single bright star and is a modern constellation devised simply to fill the otherwise vacant space in circumpolar regions between Ursa Major and Auriga.

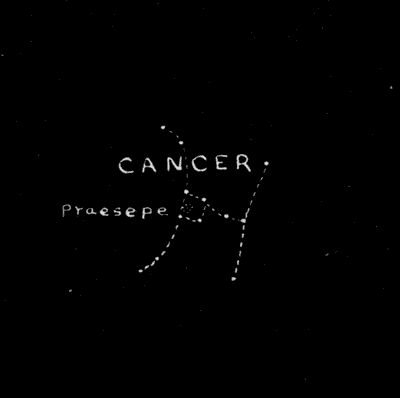

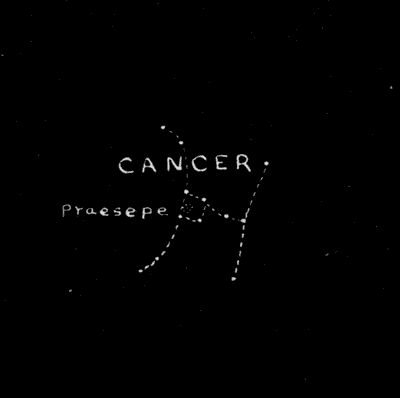

April—Cancer

Just south of the zenith at this time, and lying between Gemini and Leo, is Cancer, The Crab, the most inconspicuous of all the zodiacal constellations. There are no bright stars in this group, and there is also nothing distinctive about the grouping of its faint stars, though we can readily find it, from its position between the two neighboring constellations of Gemini and Leo by reference to the chart.

In the position indicated there we will see on clear evenings a faint, nebulous cloud of light, which is known as Praesepe, The Beehive, or as The Manger, the two faint stars flanking it on either side being called Aselli, The Asses. This faint cloud can be easily resolved by an opera-glass into a coarse cluster of stars that lie just beyond the range of the unaided human vision.

To the ancients, Praesepe served as an indicator of weather conditions, and Aratus, an ancient astronomer, wrote of this cluster:

"A murky manger, with both stars

Shining unaltered, is a sign of rain.

If while the northern ass is dimmed

By vaporous shroud, he of the south gleam radiant,

Expect a south wind; the vaporous shroud and radiance

Exchanging stars, harbinger Boreas."

This was not entirely a matter of superstition, as we might possibly imagine, for the dimness of the cluster is simply an indication that vapor is gathering and condensing in the atmosphere, just as a ring around the moon is an indication of the same gathering and condensation of vapor that precedes a storm.

Some centuries ago the sun reached its greatest distance north of the equator—which occurs each year at the beginning of summer—at the time when it was passing through the constellation of Cancer. Our tropic of Cancer, which marks the northern limit of the torrid zone, received its name from this fact. At the time when the sun reaches the point farthest north, its height above the horizon changes very little from day to day, and for a short time it appears to be slowly crawling sideways through the heavens, as a crab walks, and for this reason, possibly, the constellation was called Cancer, The Crab. At the present time the "Precession of the Equinoxes," or westward shifting of the vernal equinox—the point where the sun crosses the equator going north in the spring—brings the sun, when it is farthest north, in Gemini instead of in Cancer. At the present time, then it would be more accurate to speak of the tropic of Gemini, though this in turn would be inaccurate after a lapse of centuries, as the sun passed into another constellation at the beginning of summer. The tropic of Capricorn, which marks the farthest southern excursions of the sun in its yearly circuit of the heavens, should also more appropriately be called the tropic of Sagittarius, as the sun is now in Sagittarius instead of Capricornus at the time when it is farthest south, though the point is slowly shifting westward into Scorpio.

Mythology tells us that Cancer was sent by Juno to distract Hercules by pinching his toes while he was contending with the many-headed serpent in the Lernean swamp. Hercules, the legend says, crushed the crab with a single blow, and Juno by way of reward placed it in the heavens.

In Cancer, according to the belief of the Chaldeans, was located the "gate of men," by which souls descended into human bodies, while in Capricornus was the "gate of the gods," through which the freed souls of men returned to heaven.

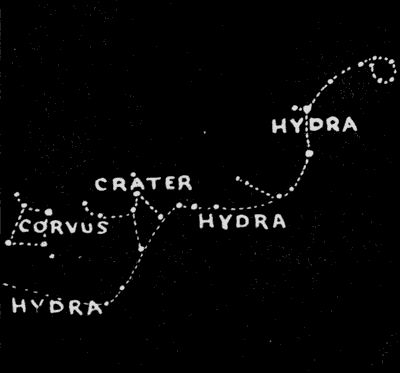

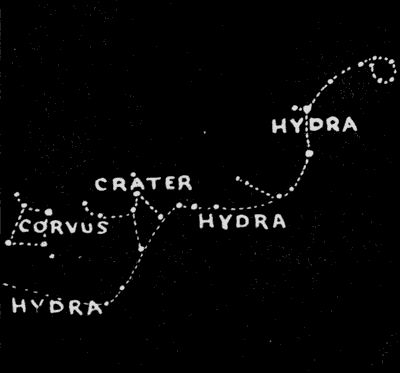

April—Hydra

Hydra, the many-headed serpent with which Hercules contended, is represented by a constellation of great length. It extends from a point just south of Cancer, where a group of faint stars marks the heads, to the south and southeast in a long line of faint stars. It passes in its course just south of Crater and Corvus, the two small star-groups below Leo (see constellations for May), which are sometimes called its riders, and it also stretches below the entire length of the long, straggling constellation of Virgo. At this time we can trace it only to the point where it disappears below the horizon in the southeast. It contains but one bright star, Alphard, or Cor Hydrae as it is also called, standing quite alone and almost due south at this time. Hydra, as well as Lynx and Cancer, contains no noteworthy or remarkable object and consists chiefly of faint stars. Alphard is, in fact, the only bright star that we have in the constellations for this month. It chances that these three inconspicuous star-groups, Lynx, Crater, and Hydra, lie nearest to the meridian at this time, separating the brilliant groups of winter from those of the summer months.

April—Lynx