VI MAY

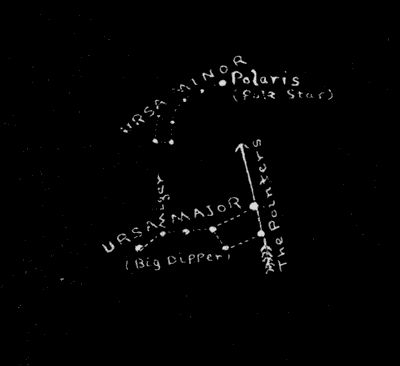

Ursa Major, the Great Bear, and Ursa Minor, the Lesser Bear, or, as they are more familiarly called, the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper, are the best known of all the constellations visible in northern latitudes. They are called circumpolar constellations, which means "around the pole." For those who live north of 40° N. Lat. they never set, but can be seen at all hours of the night and at all times of the year. In fall and winter evenings Ursa Major lies below the pole and near the horizon, and so is usually hidden more or less from view by trees or buildings. It is during the early evening hours of late spring and summer that this constellation is seen to the best advantage high in the sky above the pole. If one looks due north at the time mentioned, it will be impossible to miss either of these constellations.

To complete the outline of the Great Bear, it is necessary to include faint stars to the east, which form the head of the Bear, and other faint stars to the south, which form the feet, but these are all inconspicuous and of little general interest.

The two stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper through which an arrow is drawn in the chart, are called the Pointers, because an imaginary line drawn through these two stars and continued a distance about equal to the length of the Big Dipper, brings us to the star Polaris, or the North Star, at the end of the handle of the Little Dipper, which is very close to the north pole of the heavens, the direction in which the earth's axis points. The pole lies on the line connecting the star at the bend in the handle of the Big Dipper with Polaris, and is only one degree distant from the pole-star.

May—Ursa Major and Ursa Minor

The distance between the Pointers is five degrees of arc, and the distance from the more northerly of these two stars to Polaris is nearly thirty degrees. We may find it useful to remember this in estimating distances between objects in the heavens, which are always given in angular measure.

A small two and one-half inch telescope will separate Polaris into two stars eighteen seconds of arc apart. The companion star is a faint white star of the ninth magnitude.

Twenty years or so ago it was discovered with the aid of the spectroscope that the brighter of the two stars was also a double star, but the two stars were so close together that they could not be seen as separate stars in any telescope. Later it was found that the brighter star was in reality triple, that is, it consists of three suns close together. The faint white companion star formed with these three suns a system of four suns revolving about a common center of gravity. Still more recently it has been discovered that the brightest of these four suns varies regularly in brightness in a period of a little less than four days. It belongs to the important class of stars known as Cepheid variable stars, whose changes of light, it is believed, are produced by some periodic form of disturbance taking place within the stars themselves.

With one exception, Polaris is the nearest to the earth of all these Cepheid variable stars, which are in most instances at very great distances from the solar system. The latest measurements of the distance of Polaris show that its light takes about two centuries to travel to the earth, or, in other words, that it is distant two hundred light-years.

Like all Cepheid variables, Polaris is a giant star. It gives forth about five hundred and twenty-five times as much light as our own sun. If Polaris and the sun were placed side by side at a distance of thirty-three light-years, the sun would appear as a star of the fifth magnitude, just well within the range of visibility of the human eye, while Polaris would outshine Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens.

As a practical aid to navigators, Polaris is unsurpassed in importance by any star of the northern hemisphere of the heavens. At the equator the pole-star lies in the horizon; at the north pole of the earth it is in the zenith or directly overhead. Its altitude or height above the horizon is always equal to the latitude of the place of observation. As we travel northward from the equator toward the pole we see Polaris rise higher and higher in the sky. In New York the elevation of Polaris above the horizon is forty degrees, which is the latitude of the city.

The Pointers indicate the direction of Polaris and the true north, while the height of Polaris above the horizon tells us our latitude. These kindly stars direct us by night when we are uncertain of our bearings, whether we travel by land or sea or air. They are the friends and aids of explorers, navigators and aviators, who often turn to them for guidance.

Bryant writes thus beautifully of Polaris in his Hymn to the North Star:

Constellations come and climb the heavens, and go.

Star of the Pole! and thou dost see them set.

Alone in thy cold skies,

Thou keep'st thy old unmoving station yet,

Nor join'st the dances of that glittering train,

Nor dipp'st thy virgin orb in the blue western main.

On thy unaltering blaze

The half wrecked mariner, his compass lost,

Fixes his steady gaze,

And steers, undoubting, to the friendly coast;

And they who stray in perilous wastes by night,

Are glad when thou dost shine to guide their footsteps right.

The star at the bend in the handle of the Big Dipper, called Mizar, is of special interest. If one has good eyesight, he will see close to it a faint star. This is Alcor, which is Arabic for The Test. The two stars are also called the Horse and the Rider.

Mizar forms with Alcor what is known as a wide double star. It is, in fact, the widest of all double stars. Many stars in the heavens that appear single to us are separated by the telescope into double or triple or multiple stars. They consist of two or more suns revolving about a common center, known as their center of gravity. Sometimes the suns are so close together that even the most powerful telescope will not separate them. Then a most wonderful little instrument, called the spectroscope, steps in and analyzes the light of the stars and shows which are double and which are single. A star shown to be double by the spectroscope, but not by the telescope, is called a spectroscopic binary star.

Mizar is of historic interest, as being the first double star to be detected with the aid of the telescope. A very small telescope will split Mizar up into two stars. The brighter of the two is a spectroscopic binary star beside, so that it really consists of two suns instead of one, with the distance between the two so small that even the telescope cannot separate them. About this system of three suns which we know as the star Mizar, the faint star Alcor revolves at a distance equal to sixteen thousand times the distance of the earth from the sun.

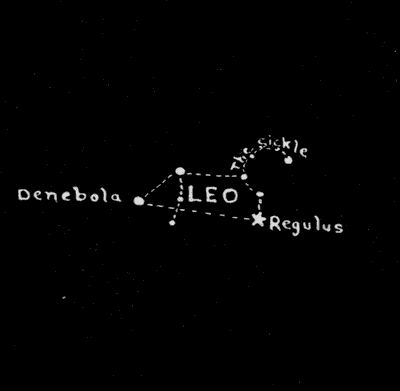

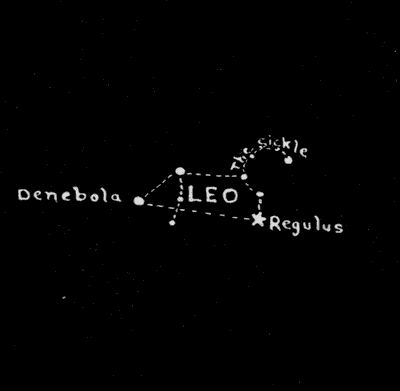

May—Leo

If we follow the imaginary line drawn through the Pointers in a southerly direction about forty-five degrees, we come to Leo, The Lion, one of the zodiacal constellations. There should be no difficulty in finding the constellation Leo, as its peculiar sickle-shaped group of bright stars makes it distinctive from all other constellations. At the time we have mentioned, that is, the early evening hours, it will lie a little to the southwest of the zenith. Leo is one of the finest constellations and is always associated with the spring months because it is then high in the sky in the evening.

Regulus is the beautiful white star which marks the handle of The Sickle, and the heart of Leo; and Denebola is the second-magnitude star in the tail of Leo.

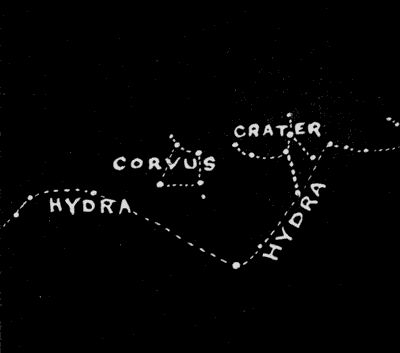

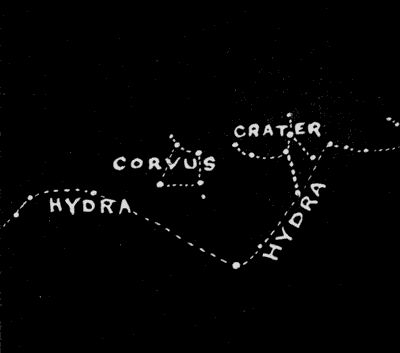

May—Corvus and Crater

Due south of Denebola, about thirty degrees, we find the small star-group known as Crater, The Cup, which is composed of rather faint and inconspicuous stars. Just east of Crater is the group known as Corvus, The Crow, which forms a very characteristic little four-sided figure of stars differing very little from one another in brightness. These two star groups lie far to the south in our latitudes; but if we lived twenty degrees south of the equator, we would find them nearly overhead, at this time of the year. Just south of Corvus and Crater we find Hydra, one of the constellations for April which extends beneath these constellations and also beneath Virgo, one of the June constellations.