Highest Post-

Male or Female

Resting Heart Rate

Caffeine Heart Rate

F

80

88

M

88

100

M

76

116

M

68

76

M

72

92

M

80

92

F

76

92

F

68

84

F

68

92

F

72

80

M

80

74

M

64

84

F

68

88

F

84

84

M

80

96

M

72

104

• On the basis of your observations, what generalization can you

make about the effect of caffeine on the human body?

Caffeine appears to increase heart rate.

• Why was it important that all students drank the same kind and

amount of soft drink?

Students will recognize that the variable they are interested in testing

is individual susceptibility to caffeine. They need to keep as many other factors in the investigation constant, such as amount and kind of soft

93

Student Lesson 4

Chemicals, the Environment, and You

drink (because different soft drinks have different amounts of caffeine), time of day for the investigation, and temperature of the classroom.

• Did all the members of the class have exactly the same results

when they drank a caffeinated soft drink?

While most members of the class will see their heart rate increase, the

amount of increase will vary significantly.

• Compare your results with those of other members of the class.

What is your individual susceptibility to caffeine?

Ask students to compare how much their heart rates increased after

exposure to caffeine. Those whose heart rates increased significantly

can draw the conclusion that they are very susceptible to caffeine.

Those whose heart rates did not increase very much, or went down,

can draw the conclusion that they are less susceptible to caffeine.

• Why might some people be more individually susceptible to the

effects of caffeine than others?

Students vary from one another in gender, size, frequency of caffeine

consumption, metabolic rates, and so on. This variability makes each

student react differently to exposure to caffeine.

• What do the results of your investigation tell you about the

possible risks to some people of ingesting the chemical caffeine?

Although research has shown that caffeine is safe to consume in

moderate amounts, doctors suggest that people who have high blood

pressure or trouble with irregular heartbeats avoid caffeine.

Extension

Ask students to examine the labels from some product packages for

Activity

directions for use and warnings. Suggest that students look at a variety

of products, such as household cleaners, cold medicines, and vitamins.

Instruct students to summarize information about the following for

each product:

• route of exposure

• dose

• individual susceptibility

Students’ summaries will vary depending on the products they choose.

Encourage them to examine at least one product that is meant for

human ingestion, such as a medication, because the product label should

contain information about dose and individual susceptibility. Remind

them that labels from some products, such as household cleaners, will

have information about routes of exposure but probably will not include

information about dose or individual susceptibility.

94

L E S S O N 5

Elaborate

What Is

the Risk?

Overview

At a Glance

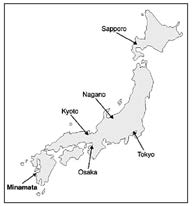

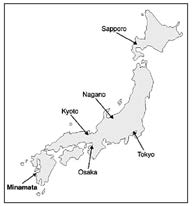

Students apply their growing understanding of the concepts of toxicology

(dose, response, individual susceptibility, potency, and threshold) to their discussion of the 1950s tragedy in Minamata, Japan. They learn how to

assess the risk to people of specific chemical hazards and make decisions about how to manage that risk.

Major Concepts

People can make some choices about chemical exposure; however, some

exposure is controlled at a level other than an individual one. Collective groups of people, such as communities and governments, seek to control

chemical exposure on a community or global level.

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will

• use their knowledge about dose, response, individual susceptibility,

and route and frequency of exposure to understand a historical

situation involving hazardous chemical exposure;

• assess the risk to people in Minamata of mercury poisoning using a

risk-assessment flow chart;

• compare their own risk of mercury poisoning with that of the people

of Minamata; and

• understand the kinds of critical choices people make about chemical

exposure and that some exposure is controlled at a level other than

an individual one, such as the community or global level.

95

Chemicals, the Environment, and You

Background

The Minamata Case Study

Information

When people living in Minamata, Japan, in the 1950s began slurring their

speech occasionally or dropping their chopsticks at a meal, no one thought much of it. Some people

cruelly laughed, claiming their

clumsy friends were acting like

the cats that were “dancing”

strangely in the street and

falling to their death in the

sea. When it seemed like more

and more people were suffering

from the mysterious lack of

coordination, the community

began to realize that something

was seriously wrong. But,

people did not know that they

were seeing the first signs of a

debilitating nervous condition

caused by ingesting mercury

(Japanese Environmental

Health Department, 2002).

We now know the tragic story of Minamata. The Minamata Bay was

polluted with the industrial waste from the Chisso Corporation, which

manufactured acetaldehyde used to make plastics. The mercury the

company used in the production process was discharged into the bay,

incorporated into bacteria, and passed through the food chain to people

living in the area. The people in the town were slowly being poisoned by

their most important food source: fish.

The consequences of such blatant polluting seem obvious to people today.

But at the time, science had not yet documented the hazards of mercury,

and environmental awareness was not pervasive. In fact, the Minamata

case has become a classic lesson in the tragedy of industrial pollution

and the need to anticipate the unexpected consequences of introducing

chemicals into the environment. Although the story is now half a century

old (and “ancient history” for today’s middle school students), it has a well-documented cause and effect, as well as a resolution. In this way, it provides a good model for teaching about risk assessment and management that

students can apply to their analysis of current exposures to chemicals.

Risk Assessment

Today, when toxicologists study the extent and type of negative effects

associated with a particular level of chemical exposure, they can use what they learn to assess the threat of that chemical to people’s health. To do this, toxicologists measure a person’s risk of exposure to the chemical.

For example, even though dioxin is considered the most toxic synthetic

chemical known, it does not pose the greatest risk to humans because the

Minamata photographs by W. Eugene Smith

potential for significant dioxin exposure is quite small. In addition, while and Aileen M. Smith.

96

the lethal dose of a chemical is an important measurement to make, it is

quite possible that a chemical will produce a very undesirable toxic effect at doses that cause no deaths at all. These lower doses may be the amount to which people are regularly exposed.

How a person is exposed to a chemical also determines the factor of risk.

In the case of a single exposure, the amount of chemical and way the body is known to respond to the chemical determine the severity of the toxic

response. In the case of repeated exposures to a chemical, it is not only the amount of chemical that counts, but also the frequency of exposure. If the body is able to rid itself entirely of the chemical before the next exposure, it is possible that each exposure is akin to a single exposure to the chemical.

If, however, the body still retains some of the chemical from the previous exposure, accumulation of the chemical can occur and eventually can reach toxic levels, even if each exposure is small.

Many of the measurements that guide toxicologists in their assessment

of human risk are based on studies of animals other than humans. This

fact, coupled with the individual susceptibility of different members of

the human population, makes it difficult to know with absolute certainty

the level of risk to which each individual is exposed. With adequate

information, however, toxicologists can predict the health risks associated with specific chemical exposures and help the human population make

informed decisions about how to limit those exposures.

Managing Risk

The built-in uncertainty of risk assessment makes it essential for people to possess enough knowledge to make decisions about their own exposures

to chemicals. With adequate knowledge, individuals can make decisions

concerning their exposure to tobacco smoke, pollutants in water, and

chemicals in food. By modifying their individual behavior, people can have some control over the chemicals they absorb into their body.

Not all decisions about chemical exposure and control can be made at

an individual level, however. Local, national, and global communities of

people are exposed to chemicals over which they have very little individual control. People are exposed to air pollution from factories and cars or

chemicals used by farmers on crops without any individual consent.

To manage a community’s risk from chemicals in the environment,

organizations and agencies set standards to protect human health.

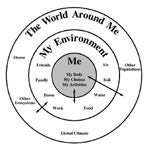

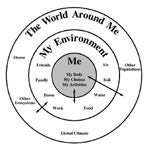

There are choices about chemical exposure over which individuals

have control (represented by the inner circle in the adjacent diagram).

Individuals are also affected by their immediate environment (their friends and family, as well as the air, soil, and water around their homes and

workplaces); the middle circle of the diagram describes influences on an

individual over which he or she has less control. Finally, the outer circle describes the world that surrounds individuals over which they have little control but that can have an impact on them. The arrows between each

concentric circle indicate that individuals, their environment, and the world at large all affect each other.

97

Student Lesson 5

Chemicals, the Environment, and You

One step in community risk management is to determine how much risk is

acceptable to people. If the chance that exposure to a particular chemical causes cancer is only 1 in 1 million, people are often less concerned than if the chance is 1 in 10. The picture becomes more complicated when societal issues weigh in (Marczewski and Kamrin, 2000). Is the exposure voluntary

(as in smoking cigarettes) or involuntary (as in pollution from a factory)?

Does it occur in the workplace or at home? Are there acceptable alternatives to the use of the toxic chemical? How would use of a safer chemical change the economic picture?

To establish some individual control over community management of

chemical exposure, people can choose to be involved with organizations

and agencies that are concerned with the prevention of toxic chemical

exposure on a community level.

Notes about Lesson 5

In this lesson, students have the opportunity to apply many of the concepts of toxicology to a scenario that involved toxic chemicals in Minamata,

Japan. By looking at a situation from the 1950s, students can recognize how far scientists and the general public have come in their understanding of chemical hazards and their knowledge of how to minimize risk from these

hazards. Students can begin to identify situations in their own lives in

which they make conscious decisions to limit their chemical exposure and

those over which they have little control.

In Advance

Web-Based Activities

Activity 1 has a Web-based component.

Photocopies and Transparencies

Materials

1 transparency of Master 5.1

• computer

1 copy of Master 5.2 for each

• overhead projector

student

• plain paper

• current event stories

students began collecting in

Lesson 1, Extension Activity

(optional)

98

Preparation

Activity 1

Arrange for students to have access to computers.

Make a transparency of Master 5.1, Risk Assessment and Management.

Duplicate Master 5.2, Minamata Disease, one for each student. To allow students to read only small amounts of the information at a time, fold along the dashed lines.

Activity 2

Gather the same materials used in Activity 1.

Extension Activity

Remind students to bring in the current event stories they began collecting in Lesson 1.

Be sure to have a transparency of Master 5.1, Risk Assessment

and Management.

ACTIVITY 1: People At Risk

Procedure

1. Remind students that there are chemicals in the environment that

cause health problems for humans. Tell students that toxicologists

study the extent and type of health problems associated with a

particular level of chemical exposure. Then, they use what they

learn to assess the threat of that chemical to the health of people in particular situations. This kind of analysis is called a risk assessment.

Display the top half of a transparency of Master 5.1, Risk Assessment

and Management.

99

Student Lesson 5

Chemicals, the Environment, and You

2. Distribute the folded sheets made from Master 5.2, Minamata Disease.

Tell students that they are going to practice the steps to making a

risk assessment by using a well-known case from Japan in the 1950s.

Instruct students to read Part I of Master 5.2. Then, discuss the

answers to the questions in Step 1 on the Master 5.1 transparency.

• Is a new health problem present?

Yes. Fish, cats, and birds were sick and dying. Also, people were

Minamata photographs by W. Eugene Smith

and Aileen M. Smith.

acting strangely.

• What are the symptoms?

People were stumbling, unable to write, fumbling with their buttons,

having difficulty balancing, falling from boats, suffering from

Content Standard F:

convulsions, and dying.

Students should develop

understanding of personal

• What do the affected individuals have in common?

health, natural hazards,

and risks and benefits.

Many work as fishermen or were in the families of fishermen.

Once students have answered the questions on the transparency, ask

them to offer ideas about what they think was contaminating the fish.

3. Instruct students to unfold the first fold, revealing Part II. Ask them to read the paragraphs and then answer the questions in Step 2 of

Master 5.1.

• What is causing the problem?

Pollution was contaminating the fish with mercury, and people were

getting sick when they ate the fish.

• What is the source of the problem?

The Chisso Corporation was dumping the mercury, so the company

was the source of the problem. It might be interesting to discuss the

role the community had in allowing the pollution of the bay to continue

by accepting compensation for poor fishing conditions. Could the

townspeople have demanded cleaner water instead of being satisfied

with a monetary solution to the problem of fewer fish for harvest?

Once students have answered the questions on the transparency, ask

them to suggest answers to the question at the end of Part II: What

made this contamination of the fish so dangerous to humans?

100

4. Instruct students to unfold the next fold, revealing Part III. Ask students to read the paragraph and then answer the questions in

Step 3 of the risk assessment (Master 5.1).

•

What are the sources of exposure to the chemical?

Content Standard E:

Students should develop

People were exposed to mercury by eating contaminated fish. The

understandings about

contamination of the fish was serious because it was a primary food

science and technology.

source for the community.

Perfectly designed

solutions do not exist.

• How much exposure are people in the area receiving?

All technological solutions

have tradeoffs, such as

People in Minamata, especially fishermen and their families, ate fish

often. They were getting a small amount of mercury often over a period

safety, cost, efficiency,

of time. Any amount of contaminated fish over 30 pounds per year is

and appearance….

likely to provide a harmful exposure to mercury.

Technological solutions

have intended benefits

• Is the exposure acute or chronic? (Is it likely to happen only once and unintended

or often over the course of time?)

consequences. Some

consequences can be

The exposure to mercury happened in Minamata over a long period of

predicted, others cannot.

time: It was a chronic chemical exposure.

5. Ask students not to unfold the last fold until directed to do so during the next activity. Discuss the information from the reading and

answer the concluding question on the risk assessment (Master 5.1):

How great is the risk to people?

Photo: Corel

Because of their dependence on fish as a primary source of food, the

potential risk of mercury poisoning from contaminated fish for people

living in Minamata was very high.

6. Play the video segment on the Web site that describes the Minamata story.

Go to the Web Portion of Student Activities page

and choose Lesson 5 ( http://science.education.nih.

gov/supplements/chemicals/student). Play the video

documentary for the students.

Because the time period and geographic location of the Minamata

tragedy are so far removed from students’ experiences, the visual

representation of the story on the Web site helps it come alive

for students.

101

Student Lesson 5

Chemicals, the Environment, and You

ACTIVITY 2: What Is Your Risk?

1. Remind students that mercury is used today in thermometers and

batteries. (Although newer thermometers now use red alcohol, many

old ones contain mercury.) Tell students that although they do not live in Minamata in the 1950s, inappropriate disposal of items containing

mercury poses a threat to their environment, even today. Since

garbage is either incinerated or covered up in landfills, mercury can

make its way into the environment through emission of burning

gases into the air or groundwater contamination. Fish contaminated

with mercury can make their way into the food supply.

2. Ask students how they think they can avoid mercury poisoning from

contaminated fish.

Most students will say that they could stop eating fish, thereby

eliminating their risk just by avoiding exposure to the mercury-

contaminated fish. Some students may indicate that the risk of

mercury poisoning provides a great excuse to avoid a less-than-

favorite food: fish.

Ask students if it is possible always to avoid a chemical in order to

eliminate possible exposure. What about a chemical in the air?

Photo: Corel

Could students choose not to breathe in order to avoid exposure to

an air pollutant?

This question brings up the issue of control. If your food supply is

varied enough, you can choose not to eat fish and still remain healthy.

(This might not be an option for an island population that depends on

fish for protein.) You cannot, however, choose not to breathe as a way

to avoid exposure to an air pollutant. You would need to find other

ways to limit your exposure to the air pollutant, like staying inside, not exercising outside, or wearing a mask that filters the air.

3. Tell students that one of the reasons for understanding the role of toxicology in human health is to empower the students to make

choices that decrease their risk of becoming ill due to exposure

to harmful chemicals. Once they know the risk from a chemical

exposure, they can manage their risk by deciding how to deal with