Stem cells are cells that have the potential to replicate themselves for indefinite periods and to divide, producing one copy of themselves and one cell of a different type ( differentiation). In humans, stem cells have been located in: the early stages of development after egg fertilization (around 5-6 days); the umbilical cord and placenta; and in several adult organs.

Regardless of their source all stem cells have two general properties:

Stem cells are capable of dividing and renewing themselves for long periods. Unlike muscle cells, blood cells, or nerve cells – which do not replicate themselves – stem cells can divide continuously and keep their innate properties.

Stem cells are undifferentiated and can give rise to multiple cell-types. Stem cells do not have any tissue-specific structures that allow them to perform specialized functions. They cannot carry molecules of oxygen through the bloodstream like red blood cells or release signals to other cells, such as permitting the body to move or speak, as nerve cells do. Although stem cells do not have any tissue-specific structures, they can give rise to differentiated cells, including red blood cells and nerve cells.

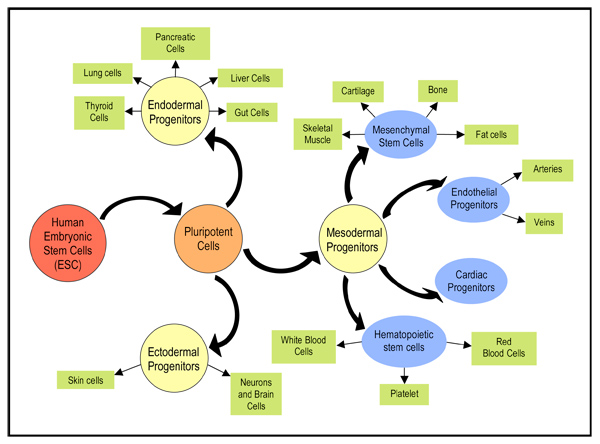

Stem cells have varying abilities to differentiate into different cell-types (see Figure 1). One type of stem cell can give rise to any other cell-type of a given organism (for example, an embryonic stem cell). Other stem cells can only give rise to cells of a given tissue type (for example, bone marrow can produce blood stem cells) or only give rise to a few cell-types in a given tissue.

Scientists are just beginning to understand the signals in a body which can trigger cell differentiation. These signals can be created within a cell, triggered by a cell’s genes, or by a neighboring cell that releases chemicals to promote differentiation in other cells. Determining what these signals are and what stem cells require to differentiate into different cell-types is a crucial research area which must be explored in order to utilize stem cells for therapies.

When cells differentiate, their abilities become more restricted. They often follow only a few prescribed pathways and can lose the capacity to replicate themselves. The ability of stem cells to replicate and remain unspecialized until they are needed is an important area of research vital to understanding human development.

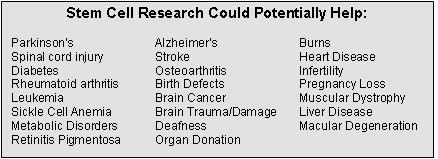

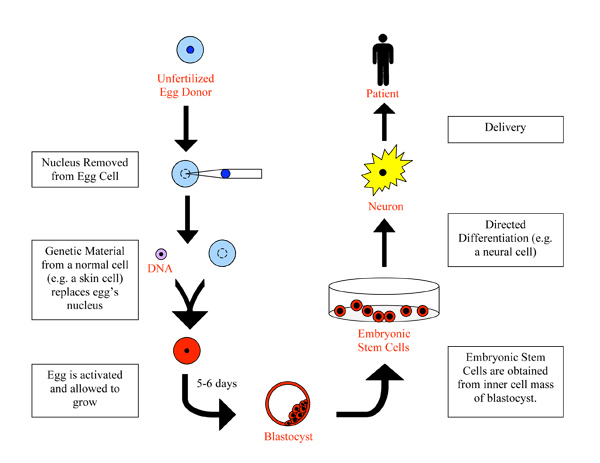

Stem cells offer a new look at old problems and diseases such as burns and diabetes. Although the field is relatively new, the impact of new discoveries could profoundly change medical research and therapy. Many of these new approaches involve the use of somatic cell nuclear transfer (sometimes known as therapeutic cloning) to produce recipient-specific tissue by creating embryonic stem cell lines.

This new area of research has great potential, but it is not without its controversies. Many ethical dilemmas are produced with the creation and destruction of human blastocysts as well as the potential to clone an entire human being ( reproductive cloning). No matter where society designates the boundary to be for this research, or whether or not stem cells can live up to our high expectations, a great deal can be learned through careful and thoughtful studies.

Embryonic stem cells are derived exclusively from a fertilized egg that has been grown in vitro for 5 to 6 days to form a blastocyst. Within a blastocyst there is a small group of about 30 cells called the inner cell mass, which will give rise to the hundreds of highly specialized cells needed to make up an adult organism. Embryonic stem cells are obtained from this inner cell mass. For research purposes, embryonic stem cells are produced specifically from eggs that have been fertilized in vitro, or in a laboratory and not inside a woman’s body, or in vivo. Embryonic stem cells can come from a frozen fertilized egg or an egg which is fertilized in vitro.

Embryonic stem cells can and do differentiate into all the specialized cells in the adult body. They could be induced to provide an unlimited source of specific and clinically important adult cells such as bone, muscle, liver or blood cells (See Figure 2).

Adult stem cells are unspecialized or undifferentiated cells found among specialized cells in an adult tissue or organ. In some adult tissues, such as in bone marrow, muscle, or brain tissue, discrete populations of adult stem cells generate replacements for cells that are lost through disease, injury, or normal wear and tear. Adult stem cells are thought to reside in an area of each tissue where they may remain quiescent, or non-dividing, for many years until they are activated by disease or tissue injury. Where they are found, adult stem cells consist of a very small population of cells within each tissue.

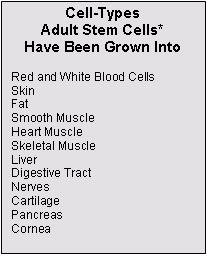

Some adult stem cells retain the ability to form into specialized tissues other than the one from which they originated. For example, blood ( hematopoietic) cells have not been proven to differentiate into nerve, skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, or liver cells (see Figure 3). There is some evidence that brain stem cells can differentiate into blood or skeletal muscle cells. However, adult stem cells have a limited number of tissues they can differentiate into and do not have the same potential as embryonic stem cells to become any cell-type.

The environment that adult stem cells grow in has an important, but poorly understood, effect on their fate. The relationship between the adult stem cell environment and its ability to differentiate into other cell-types has also not been fully explained.

Distinctions between Embryonic and Adult Stem Cells

Most importantly, adult and embryonic stem cells differ in the type of differentiated cells they can become. While embryonic stem cells can be induced to differentiate into any cell-type, adult stem cells cannot. Most adult cells can only differentiate into the types of cells found in their environment or in the particular tissue or organ where they reside. Therefore in many vital organs, adults do not have the stem cells necessary to regenerate damaged areas; thus scar tissue will develop instead.

Another key difference between embryonic and adult stem cells is the volume of cells one can isolate and grow in vitro. Large numbers of embryonic stem cells can be grown in vitro from a single blastocyst. On the contrary, adult stem cells are rare and methods of growing them still need to be perfected. In addition, due to their limited numbers, it is difficult to isolate a group of adult stem cells in pure form, without having them contaminated with differentiated cells.

Potential Uses of Stem Cells

While stem cell research is in its infancy and many of its proposed uses are hypothetical, the research has generated excitement among many scientists for its potential. One of the vital components of ongoing work is understanding the very nature of these cells; that is, to determine the conditions necessary to maintain undifferentiated stem cells as well as differentiating them along specific pathways. In order to truly determine whether or not these cells can be used therapeutically, more research must be conducted to understand the nature of the cells.

Although we are only beginning to discover what stem cells are capable of doing, scientists have proposed several potential uses.

Abnormal Cell Division. Many serious medical conditions, such as cancer and birth defects, are due to abnormal cell divisions or the inability of cells to turn themselves on and off properly. Having a better understanding of stem cells and their genetic and molecular controls would yield information about diseases and reveal potential strategies for therapies.

Drug Testing. Stem cells could be used to test new drugs or medications by differentiating them to the particular cell-types that the drugs are targeting. This would offer a short-cut for scientists to sort out chemicals that can be used to treat diseases. By testing new drugs on stem cell lines, we could perform rapid screening of hundreds of thousands of chemicals that now are tested by more time-consuming processes. This could also potentially decrease the time that it takes to get a drug to market.

Cell-Based Therapies. Stem cells could be used for cell-based therapies. Stem cells could be directed to differentiate to a specific cell-type that then could be used as a renewable source of replacement cells and tissues. In order to be useful for cell-based therapies, stem cells must be made to:

Function appropriately for the duration of the recipient’s life. Not only do the cells need to be localized and survive, but they must also behave like the original cells. Currently, there is not sufficient data showing that stem cells are functional in their new environment when they are transplanted into organs. For cell-based therapies to be successful, the new cells need to function correctly and interact properly with the original tissue.

One of the most promising uses for embryonic stem cells is the study of the complex events that occur during human development. The earliest stages of human development have previously been difficult or impossible to study. By using embryonic stem cells, these studies can be performed with the goal of preventing or treating birth defects, infertility, and pregnancy loss.

The use of embryonic stem cells can also help scientists identify how undifferentiated cells become differentiated. Since these cells have the ability to become any type of cell in the adult body, they have a larger potential for medically viable tissues which can be derived and used in cell-based therapies.