In February of 1997, Dr. Ian Wilmut announced the creation of the first cloned mammal. The report, published in the science journal Nature, described a lamb, "Dolly," which was cloned using somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). This landmark paper and the media attention it received created an immediate reaction from the public and politicians in Washington, D.C. who were concerned about the potential cloning of humans using this technique. Since Dolly’s creation, congressional leaders have been trying to find a way to prevent human cloning and other allegedly unethical medical procedures while still allowing medical research to proceed unhindered.

In late 1998, the issue was further complicated by the announcement from researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, led by Dr. James Thomson, who derived the first human embryonic stem cells from blastocysts. This marked the beginning of a new area of medical science, human embryonic stem cell research. With this new breakthrough, the issue of human cloning became considerably more complex, since SCNT was now linked to potential disease-curing research.

With each congressional session, a new crop of conflicting bills arises from both the House and the Senate, and congressional hearings are called to bring witnesses in to validate either side, but no resolution appears to be in sight. Although many polls have shown that the vast majority of Americans disapprove of research which could produce a cloned human (79% in a 2005 poll by Research!America), there is still much public debate about the ethics of embryonic stem cell research. This debate resonates in the Congress and generates the current stalemate where lawmakers are unable to reach a consensus about medical research relating to embryonic stem cells.

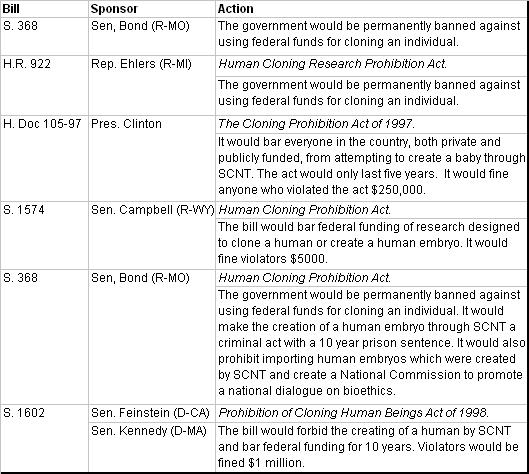

In February of 1997 after the public announcement about “Dolly”, President Clinton charged the National Bioethics Advisory Council (NBAC) to study the issue of human cloning. In June of that year, NBAC released a report which determined that reproductive cloning was immoral and requested that a moratorium should be established until subsequent laws prohibiting it were passed (with a sunset period of 3-5 years). The members also suggested that the law be written so it would not interfere with biomedical research. Taking their suggestions, President Clinton offered a legislative proposal to bar anyone (either federally or privately funded) from attempting to clone a human through SCNT for 5 years. President Clinton’s proposal was announced after several bills in the House and Senate had already been introduced (see Table 1). However, due to the fear that Congress was acting too quickly and might bar valid research, the majority needed to pass these bills was never attained and thus no legislation limiting such cloning was ever successfully passed into law.

In November of 1998, after Dr. Thomson announced the creation of the first human embryonic stem cell line, President Clinton asked NBAC to specifically address human embryonic stem cell research, which had not been discussed in 1997. In 1999, the NBAC recommended that federal funding should be used to support both the research and creation of human embryonic stem cells. They also suggested amending the ban on embryo research (the Dickey Amendment) to allow the derivation and use of embryonic stem cells.

However, before the results of the NBAC deliberations were announced, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), specifically the legal council for the DHHS, determined that federal law (the Dickey Amendment) prohibited the use of federal funds to create human embryonic stem cell lines, but they did believe that it was legal to fund research on already existing lines. Private sources were never barred from deriving their own human embryonic stem cell lines and were actively pursuing this area of research. The NIH released guidelines for the federal funding of human embryonic stem cell research for public comment in 1999, followed by an updated version in 2000 in the Federal Register. Before NIH was able to grant money in response to research proposals, a new administration (President George W. Bush) took office and the previous rulings by the DHHS and NIH were set aside.

Meanwhile in the Senate, the Specter-Harkin bill (S.2015) was introduced as the Stem Cell Research Act of 2000. It called for the federal funding of the derivation and use of human embryonic stem cells from spare donated embryos (IVF), as long as the research did not lead to "reproductive cloning of a human being.” This marked the first of many bi-partisan bills that Congress would see on this issue. The Specter-Harkin bill, like many future bills, was not passed into law.

When President Bush took office, one of his first actions was to temporarily stop all federal funding of human embryonic stem cell research (no grant had been given) while his administration considered their actions. On August 9, 2001, after several months of deliberation, President Bush announced that he would allow the federal funding of the research of human embryonic stem cells, but only those that had been derived before the date of the announcement could be used. Thus, no new embryonic stem cells could be created with federal funds, nor could federal funds be used to do research on new lines create after the August 9, 2001 deadline. NIH estimated at the time that there were as many as 60-75 cell lines available for research. However, since that time, NIH has revised its numbers downward. By the 2004 presidential campaign, NIH had only 22 lines available (see insert “Effect of President Bush’s Stem Cell Policy”).

Since the President’s August 9, 2001 decision, embryonic stem cell policy has remained unchanged. In November 2001, President Bush established the President’s Council on Bioethics (PCB), a group of experts (similar the NBAC), to address the issues of human cloning, embryonic stem cell research and other bioethical issues. In Congress, new bills were introduced in the 107th and 108th congress, and the Weldon-Stupak bill was passed in House in 2001 and 2003 to ban all forms of cloning and the use of SCNT, but neither passed in the Senate. Almost every year we see each political side introduce their version of a law which would outlaw all human cloning or only reproductive cloning and either outlaw or permit the use of embryonic stem cells, but nothing has been signed into law.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the congressional debate is the fact that views on the topic do not necessarily follow traditional party lines or a person's opinion on abortion or right to life. This new debate has produced the most unlikely bipartisan partnerships and has resulted in a deadlock in Congress, which has sharply constrained federally funded research on embryonic stem cells and human cloning. At the same time, the deadlock has virtually left the privately funded research involving embryonic stem cells and human cloning completely unregulated.

Momentum for expanding federal funding for embryonic stem cell research began to build again as the 2004 presidential campaigns kicked into gear. In April of 2004, 206 members of the House of Representatives (out of 435) signed a letter to President Bush urging him to expand the current federal policy on embryonic stem cell research to include new lines developed after August 9, 2001. Following the House’s lead, the Senators that advocated embryonic stem cell research also wrote a letter to President Bush with 58 signatures (out of 100). On May 10, 2004 former First Lady Nancy Reagan publicly supported embryonic stem cell research at a fundraiser for juvenile diabetes. Although privately she had supported the research with personal letters to congressmen, this was her first public statement on the topic. Nancy Reagan and the Reagan family are often thought of as icons for the Republican Party and conservative ideals. This public acceptance led the way for other Republicans to support the issue. One month later, President Reagan, a victim of Alzheimers, passed away. Stem cell research was immediately brought into the forefront as a campaign issue for the 2004 election. Senator Kerry supported the expansion of the research, while the President Bush explained his current policy and promised to maintain the status quo.

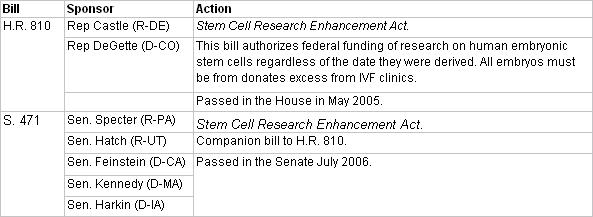

With the return of President Bush to office in 2005, the possibility for changing the current federal policy seems unlikely. However, in May 2005, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act, perhaps the most significant legislative advance in the support of stem cell research (see Table II). Its passage was the result of an initiative from the leaders in both parties. The bill amends the Public Health Service Act to provide for stem cell research by stating that cells donated from excess supplies from IVF clinics are viable for use. It stipulates that these donations are to be made from embryos determined never to be implanted in a woman and under informed consent without any financial inducements. The bill goes on to say that reports of research carried out under these guidelines should be presented each fiscal year. The Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act needed to be passed by the U.S. Senate, and although the Senate Majority Leader, Senator Bill Frist (R-TN) promised to bring it forward in 2005, the vote did not occur until July 2006. As he promised in May 2005, President Bush vetoed the bill on July 19, 2006 (the first use of the Presidential veto by Bush) and Congress was unable to override it.

With or without the expansion of federal funding, some states (such as California, Massachusetts, and New Jersey) are beginning to pick up the reins by passing their own laws related to embryonic stem cell research (see page 15 “State Cloning Legislation”). In November 2004, Californians (with 59% of the vote) approved Proposition 71, or the California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, which called for the creation of a California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) and authorized $3 billion of state funds to support the effort over the next five years. The proposal also established the right to conduct embryonic stem cell research in California, but prohibits reproductive cloning. President Bush’s policy only limits federal funding, but does not make the research itself illegal therefore the states are able to determine how they wish to regulate and fund research using state funds. CIRM supports embryonic stem cell (and adult stem cell) research regardless of the date the cells were generated, to create new cell lines, and to use SCNT to create cell lines with specific genes. This new institute is expected to attract stem cell researchers and investors to California allowing it to corner the market on any promising findings.

Despite the passage of Proposition 71, several obstacles have delayed its implementation in California. A lawsuit by taxpayer groups contended that CIRM could not sell bonds backed by taxpayer money to fund research, because it is not under direct state control. Bond sales that would be used to fund the institute are on hold until the lawsuit is settled. In April 2006, the court ruled in favor of CIRM, but the case is still in appeals. Furthermore, CIRM needed time to determine the rules for awarding grants, conducting research, and handling patent rights before it started funding grants. However, in April 2006 CIRM was still able to award their first round of grants, which totaled $12.1 million, and in July 2006 California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger agreed to give the institute a $150 million loan to help while litigation was pending.