2.How Ecologically Based Pest Management Works

To bring ecological pesT managemenT to your farm, consider three key strategies:

-

Select and grow a diversity of crops that are healthy, have natural defenses against pests, and/or are unattractive or unpalatable to the pests on your farm. Choose varieties with resistance or tolerance to those pests. Build your soil to produce healthy crops that can with- stand pest pressure. Use crop rotation and avoid large areas of mono- culture.

-

Stress the pests. You can do this using various management strategies described in this book. Interrupt their life cycles, remove alternative food sources, confuse them.

-

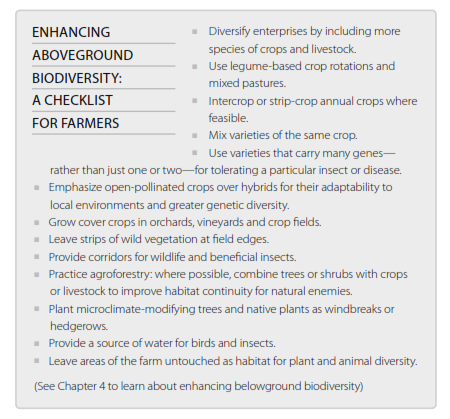

Enhance the populations of beneficial insects that attack pests. Intro- duce beneficial insects or attract them by providing food or shelter. Avoid harming beneficial insects by timing field operations carefully. Wherever possible, avoid the use of agrichemicals that will kill benefi- cials as well as pests.

EBPM relies on two main concepts:

Biodiversity in agriculture refers to all plant and animal life found in and around farms. Crops, weeds, livestock, pollinators, natural enemies, soil fauna and a wealth of other organisms, large and small, contribute to biodiversity. The more diverse the plants, animals and soil-borne organ- isms that inhabit a farming system, the more diverse the community of pest-fighting beneficial organisms the farm can support.

Biodiversity is critical to EBPM. Diversity, in the soil, in field boundar- ies, in the crops you grow and how you manage them, can reduce pest problems, decrease the risks of market and weather fluctuations, and elimi- nate labor bottlenecks.

Biodiversity is also critical to crop defenses: Biodiversity may make plants less “apparent” to pests. By contrast, crops growing in monocultures over large areas may be so obvious to pests that the plants’ defenses fall short of protecting them.

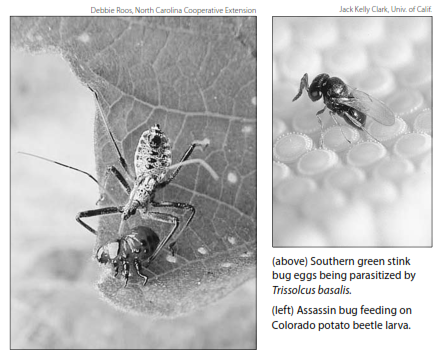

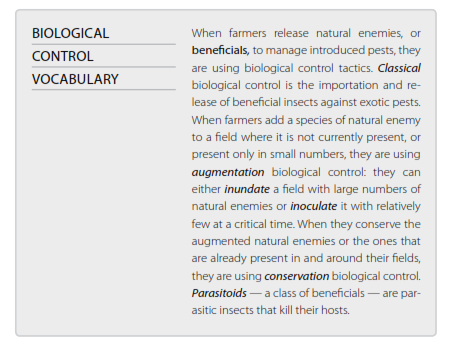

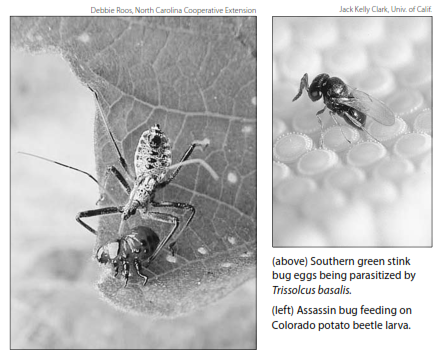

Biological control is the use of natural enemies — usually called “ben- eficial insects” or “beneficials” — to reduce, prevent or delay outbreaks of insects, nematodes, weeds or plant diseases. Biological control agents can be introduced, or they can be attracted to the farming system through ecosystem design.

Naturally occurring beneficials, at sufficient levels, can take a big bite out of your pest populations. To exploit them effectively, you must:

1) identify which beneficial organisms are present;

2) understand their individual biological cycles and resource requirements; and

3) change your management to enhance populations of beneficials.

The goal of biological control is to hold a target pest below economically damaging levels — not to eliminate it completely — since decimating the population also removes a critical food resource for the natural enemies that depend on it.

In Michigan, ladybugs feed on aphids in most field crops or — if prey is scarce — on pollen from crops like corn. In the fall, they move to for- est patches, where they hibernate by the hundreds under plant litter and snow. When spring arrives, they feed on pollen produced by such early- season flowers as dandelions. As the weather warms, they disperse to al- falfa or wheat before moving on to corn. Each component of biodiversity — whether planned or unplanned — is significant. For example, if dande- lions are destroyed during spring plowing, the ladybugs lose an important food source. As a result, the ladybugs may move on to greener pastures, or fail to reproduce, reducing the population available to manage aphids in your cash crop.

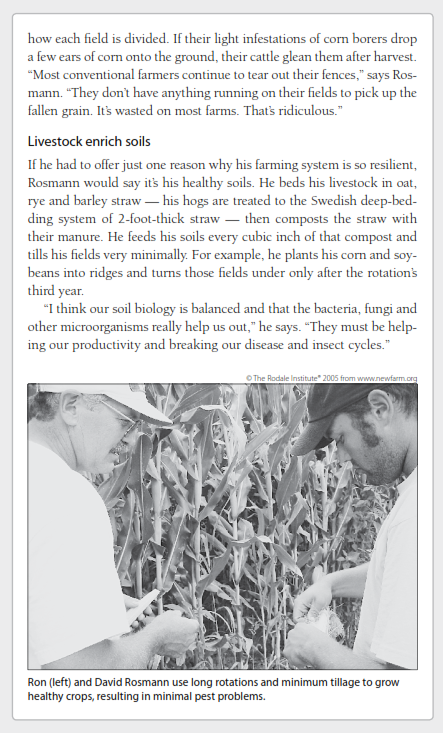

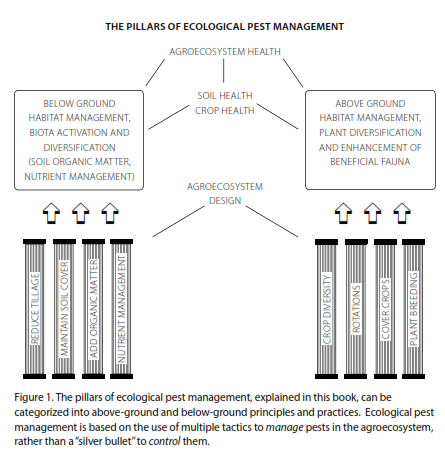

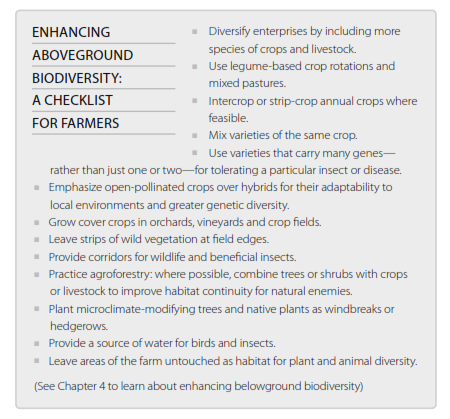

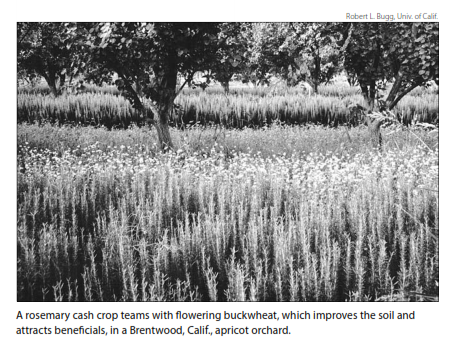

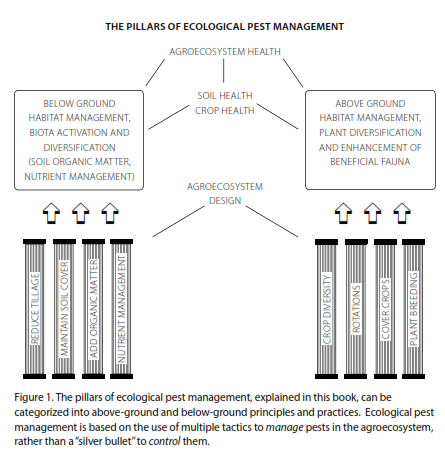

Research shows that farmers can indeed bring pests and natural enemies into balance on biodiverse farms by encouraging practices that build the great- est abundance and diversity of above- and below-ground organisms (Figure 1). By gaining a better understanding of the intricate relationships among soils, microbes, crops, pests and natural enemies, you can reap the benefits of biodiversity in your farm design. Further, a highly functioning diversity of crucial organisms improves soil biology, recycles nutrients, moderates micro- climates, detoxifies noxious chemicals and regulates hydrological processes.

What Does a Biodiverse farm look like?

Agricultural practices that increase the abundance and diversity of above- and below-ground organisms strengthen your crops’ abilities to withstand pests. In the process, you also improve soil fertility and crop productivity. Diversity on the farm includes the following components:

-

Spatial diversity across the landscape (within fields, on the farm as a whole and throughout a local watershed)

-

Genetic diversity (different varieties, mixtures, multilines, and local Germplasm)

-

Temporal diversity, throughout the season and from year to year (different crops at different stages of growth and managed in different ways)

Ideally, agricultural landscapes will look like patchwork quilts: dissimi- lar types of crops growing at various stages and under diverse manage- ment practices. Within this confusing patchwork, pests will encounter a broader range of stresses and will have trouble locating their hosts in both space and time. Their resistance to control measures also will be hampered.

Plant diversity above ground stimulates diversity in the soil. Through a system of checks and balances, a medley of soil organisms helps maintain low populations of many pests. Good soil tilth and generous quantities of organic matter also can stimulate this very useful diversity of pest-fighting soil organisms.

As a rule, ecosystems with more diversity tend to be more stable: they exhibit greater resistance — the ability to avoid or withstand disturbance — and greater resilience — the ability to recover from stress.