THE SIMPLON.

[Pg 167]

It was in the spring of 1859 that Miss Bremer set out for the East. The voyage, to one of so vivid an imagination and of such profound religious impressions,

[Pg 168]

was full of living interest. She spent long, solitary hours on the deck of the vessel that conveyed her, and allowed her fancy free course over that sea with a thousand historic memories—the Mediterranean. With vigilant eye she watched the waves as they rolled past with glittering crests of foam, and the lights and shadows which chased one another in swift succession over the purple expanse, as sunshine or cloud rested on the bosom of the sapphire sky.

"The heavens," she exclaims, "declare the glory of God, and the firmament sheweth His handiwork. Words are powerless to describe the beauty of the day, and the scene which developed before me. We were sailing on the sea of Syria towards the East—the country of the morning—and what a brightness shone around us! I think that never before had I seen the sun so luminous, so instinct with flame, or the sky and the sea so transparent. The latter is of a deep blue, lightly rippled; here and there small wave-crests, white with foam, surge up, like lilies, from the infinite depths. The air is soft and mild; sometimes the clouds unite above our heads and slide downwards into the west, while the eastern portion of the celestial vault is serene and pure as a diamond of the finest water. Above and around us we see only the sky and the sea, but they are calm and beautiful."

The Holy Land comes in sight, and a flood of emotions rushes upon our poet's soul. "David," she says, "did not rise earlier than I to see the day break

[Pg 169]

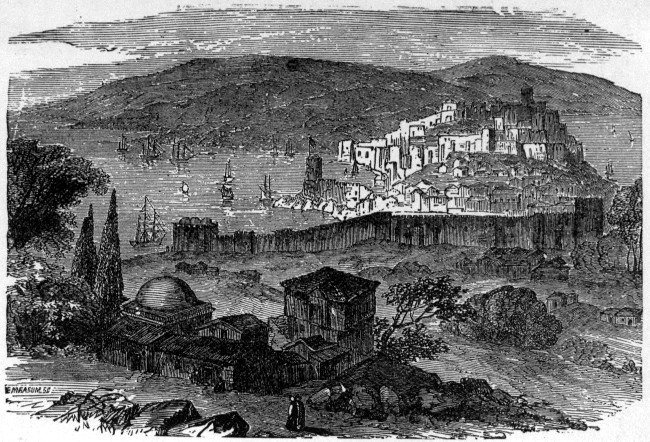

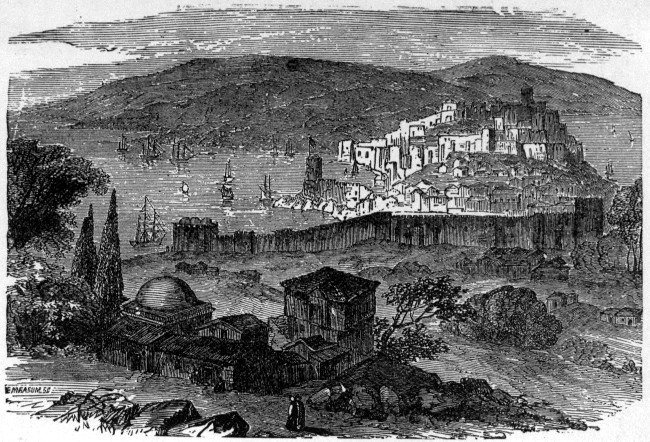

over the shores of Palestine. A fire-red cloud was spread like an arch above the verdurous hills, green with palms and other trees. Upon a height near the shore was grouped a mass of houses of grey stone, with low cupola roofs.

Here and there the palm-trees towered among them. It was Jaffa, the ancient Joppa, one of the oldest cities in the world. In the distance rose a chain of deep blue mountains, perpendicular as a wall; it was the Judæan chain.

Further to the west, another considerable chain descended seaward; that was Carmel. At a still greater distance, in the same direction, and in the interior of the country, is a lofty mountain, snow-crowned, and, beyond that wall of rock, invisible to our eyes, lay Jerusalem!"

Landing at Joppa, Miss Bremer and her party hired horses to carry them to the Holy City; but it was not without much mental perturbation that the novelist, who was but an indifferent equestrian, saw herself at the mercy of a young and fiery courser. On this occasion she gained two victories—one over herself and one over her steed, whose ardent impatience she contrived to master.

The small caravan with which Miss Bremer travelled included a Russian princess, two boyars, and some Englishmen; among others there was a professor with a cynical smile and a sarcastic wit, who possessed a happy faculty of describing, in epigrammatic phrase and always at the right moment, the more noticeable features of the manners of the natives. While the first-named

[Pg 170]

of these eminent personages rode in advance, Mr. Levison, the professor, remained by the side of Miss Bremer in the rear. Between the two cultured minds there was a certain bond of sympathy, and the length of the journey was beguiled by their animated conversations.

The professor amused himself by calling our novelist Sitti, an Arabic title bestowed upon women of high rank, and almost equivalent to that of "princess." Abhul, the guide, overhearing it, inquired if she were a kinswoman of the Sultan of Prussia, Frederick! "Yes," answered Mr. Levison, gravely, "she is a kinswoman, but a distant one."

And then he apprised his fellow-traveller of the new dignity he had conferred upon her.

This was sufficient to convert Abhul into her devoted slave. He was mightily proud of attending, and acting as guide to, a princess of royal blood. He almost went down on his knees before her; his attentions were unremitting.

The title which had been flashed before him produced on his commonplace mind a thousand times the effect that would have been produced by the knowledge that, plain little middle-class dame as she was, the humble Swedish lady was infinitely more celebrated than three-fourths of the princesses of Europe. But there are hundreds of our own compatriots who are quite as eager tuft-hunters as this poor Arab guide! John Bull dearly loves "a lord,"

while before "a princess" his soul creeps and grovels in infinite abasement.

[Pg 171]

"This ridiculous mania for titles which overwhelmed the guide Abhul" is, nevertheless, in M. Cortambert's opinion, "one of the most pronounced characteristics of the boastful and childish genius of the Orientals. The Turks and Arabs cannot believe in the importance of personages without titles of distinction; and hence the smallest prolétaire who can equip a caravan is saluted with the name of excellency. M. de Lamartine was hailed as prince and lord; he was supposed, I believe, to belong to the House of Orleans. One of our friends, an artist of high merit, by no means desirous of being taken for that which he was not, and valuing more highly his personal repute than all the titles in the world, could not shake off the rank of prince, which welcomed him at every village.

Since the visit of M. de Lamartine every French traveller seems to be regarded as a seigneur of illustrious lineage.

One easily understands that the purse of the tourist was the first to suffer from this circumstance. Several times our friend endeavoured to set his guide right, but in vain; the moukra was unwilling to pass, in the eyes of his companions, for the conductor of a private individual. By elevating his master he thought that he was raising himself."

Frederika Bremer did not allow her supposititious title of Sitti to blind her to the fact that she was before all a poet and a woman of letters. On entering Jerusalem she gave the reins to her imagination, and set herself to work on one of those delightful letters which

[Pg 172]

afterwards formed the basis of a complete narrative of her Eastern tour. "I raise my hands," she says, "towards the mountain of the house of the Lord, experiencing an indescribable thankfulness for my safe arrival here. I am in Jerusalem; I dwell upon the hill of Zion—the hill of King David. From my window the view embraces all Jerusalem, that ancient and venerable cradle of the grandest memories of humanity—the origin of so many sanguinary contests, so many pilgrimages, hymns of praise, and chants of sorrow."

Everybody knows what constitutes a traveller's life in Palestine: a succession of pilgrimages to the several places connected with Old Testament history, or with the life of our Lord; a constant renewal of those touching experiences which so deeply impress the heart and brain of every Christian. Even the freethinker cannot gaze without emotion on the shrines of a religion which has so largely affected the destinies of humanity and the currents of the world's history. What, then, must be the feeling with which they are regarded by those to whom that religion is the sure promise of eternal life? Not Greece, with its memories of poets, sages and patriots; its haunted valleys and mysterious mountain-tops; nor Italy, with its glories of art and nature, and its footprints of a warrior-people, once rulers of the known world, so appeals to the thoughtful mind as does the Holy Land, in the fulness of its sanctity as the home and dwelling-place of Jesus Christ.

But the attention of Miss Bremer was not wholly given

[Pg 173]

to the hallowed scenes by which she was surrounded. In the East, as in the West, she reverted to the question of woman's independence, the restoration of her sex to its natural and legitimate freedom. What she saw was not of a nature to cheer and encourage her. Nowhere else is the condition of woman so deplorable; not so much because she is deprived of her liberty as because she is condemned to the most absolute ignorance. And in this ignorance lies one of the principal causes of Oriental degeneracy; for the young, being brought up in the polluted atmosphere of the harem, undergo a fatal enervation of body and soul, and imbibe the germs of the most fatal vices.

One day, in company with several young persons of her own sex, Frederika Bremer paid a visit of courtesy to the wife of a sheikh, who, when informed that the ladies she had admitted to her presence were unmarried, manifested the liveliest surprise, and added that it was a great shame. The girls laughingly pointed to Miss Bremer as being also a spinster; whereupon their hostess threatened to withdraw, declaring herself overwhelmed, and, indeed, almost scandalized by such a revelation. However, on reaching the threshold she turned back, and desired to know what had induced the European lady to remain unmarried. The reasons given in reply must have been, we suppose, of a shocking character, since she cut them short by a declaration that she did not wish to hear such things spoken of.

To this example of the complete condition of moral

[Pg 174]

dependence to which even the wives of sheikhs are degraded, Miss Bremer adds another and not less characteristic fact. She asked several young women, distinguished by their eager and animated air, whether they had no desire to travel and see Allah's beautiful earth.

"Oh no," they replied, "for women that would be a sin!"

Women bred in this state of mental and moral degradation can never play an important part in the regeneration of the East.

A philosopher first, a poet after, and sometimes a painter, such is Frederika Bremer. She does not often paint a picture, however; when she does, it is brightly coloured, and its details are carefully elaborated; but her skill is more favourably displayed in portraiture. Her palette is not rich enough in glowing colours to reproduce fairly the warm luxuriant landscapes of the East. For this reason she excels in a sketch like the following, where she deals not with sky, and sea, and mountain, but the humanity in those types of it which crowd the streets and lanes of the Holy City:—

"The population of Jerusalem," she says, "I would divide into three classes: the smokers, the criers, and the mutes or phantoms. The first-named, forming in groups or bands, are seated outside the cafés smoking, while youths in the pretty Greek costume hasten from one to another with a wretched-looking coffee-pot and pour out the coffee—

the blacker it is the more highly

[Pg 175]

it is esteemed—into very small cups. With an air of keen satisfaction the smokers quaff it, drop by drop.

Frequently one of them delivers himself of a recital with very animated gestures; the others listen attentively, but you seldom see them laugh. In the café may often be heard the sound of a guitar, accompanied by a dull monotonous strain, in celebration of warlike exploits or love adventures; the Arabs give to it their pleased attention. In the bazaars, in the shops, wherever a pacific life predominates, smokers are met with. Those wearing a green turban spring from the stock of Mohammed, or else have performed the pilgrimage to Mecca and learned the Koran by heart, which raises them to the rank of holy men.

"The criers' class of Jerusalem consists of all who sell in the streets, of the camel and donkey drivers, and of the country-women who daily bring fuel, herbs, vegetables, and eggs, into the city. They generally station themselves and their wares on the Place de Jaffa, and scream in a frightful manner; one would think they were quarrelling, when, in reality, they are only gossiping. These women allow their dirty mantles or veils to fall from the head down upon the back, and do not cover the face. They are always decked and sometimes plated with silver ornaments. Silver coins, strung together, are carried in bands across the forehead, and hang down the cheeks.

Their fingers are covered with rings and their wrists with bracelets. Not unfrequently you will see very young girls with the face framed in silver

[Pg 176]

money, to correspond with their head-gear—a small cap or hood embroidered with Turkish piastres, set as close together as the scales of a fish.

"I have heard it said that this cap is a maiden's dower. The country-women are often remarkable for a kind of savage beauty, but generally they are ugly, with an expression of rudeness and ill-nature. They are a collection of sorceresses, whom I feared more than the men of the same class, though the latter assuredly did not inspire me with much confidence.

"The Arab women of high rank, enveloped in long white mantles, and with their faces hidden by a close veil of black, yellow, or blue gauze, form my third division. They walk, or rather totter, through the streets in numerous groups or bands, shod with yellow slippers or bottines, to enjoy a promenade outside the Jaffa Gate. You never hear them utter a word in the streets, nor do they pause for a moment. If that black or yellow object approach you, covered with her white veil, and turn in your direction, it is with an expressive, a piercing, questioning glance; but you cannot discover nor even divine the face concealed by that coloured gauze. These poor dumb phantoms, who are all the more to be pitied because they have no idea that they need pity, generally betake themselves to the cemeteries, where, seated under the olive trees, they spend the day in doing nothing."

The ease, grace, and dramatic power of this description no reader will question.

[Pg 177]

After visiting most shrines of interest in the Holy Land, Miss Bremer extended her tour to the Turkish sea-coast, and investigated all that was worth seeing at Beyrout, Tripoli, Latakia, Rhodes, Smyrna, and Constantinople. In bidding farewell to the East, she expressed her joy and delight at having seen it, but added that not all its gold, nor all its treasure, would induce her to spend her days in its indolent and luxurious atmosphere. She loved the West, with its intellectual activity and deep moral life, its progress and its aspirations after the higher liberty. The inertia of the East irritates a strong brain almost to madness.

Her next pilgrimage was to classic Greece, the land of Solon and Lycurgus, Pericles and Pisistratus, Æschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Demosthenes—the land of Byron and Shelley—the land of poetry and patriotism, of the myths of gods and the histories of heroes—the land which Art and Nature have fondly combined to enrich with their choicest treasures. The impression it made upon her was profound. Writing at Athens, she says:—

"I confess that the effect produced upon me here by life and the surrounding objects makes me almost dread to remain for any length of time; dread, lest beneath this clear Olympian heaven, and amid all the delightful entertainment offered to the senses, it might be possible, not, indeed, to forget, but to feel much less forcibly the great aim and purpose of that life for which the God-Man

[Pg 178]

lived, died, and rose again from the dead. 'They who cannot bear strong wines should not make use of them.' For this reason, therefore, I shall soon leave Greece, and return to my Northern home, the cloudy skies and long winters of which will not delude me into finding an earthly existence too bewitchingly beautiful. Yet am I glad that I shall be able to say to the men and women in the far North, 'If there be any one among you who suffers both in body and soul from the bleak cold of the North, or from the heavy burden of its life, let him come hither. Not to Italy, where prevails too much sirocco, and the rain, when it once begins, rains as if it would never leave off; no, but hither, where the air is pure as the atmosphere of freedom, the heavens as free from cloud as the dwellings of the gods; where the temples on the heights lift the glance upwards, and the sea and the mountains expand vast horizons to the eye, rich in colour, in thought, and in feeling; where all things are full of hope-awakening life—

antiquity, the present, and the future. Let him, beneath the sacred colonnades on the hills, or in the shade of the classic groves in the valleys, listen anew to the divine Plato, enjoy the grapes of the vales of Athéné, the figs from the native village of Socrates, honey from the thyme-scented hills of Hymettus and Cithæron, feed the glance and the mind, the soul and the body, daily with that old, ever-young beauty—that which was, and that which now springs up to new life, and he will be restored to his usual vigour of health; or, dying, will thank God that

[Pg 179]

the earth can become a vestibule to the Father's home above.'"[15]

"I shall soon leave Greece," she writes; but the charm of Hellas proved too powerful for her, and she spent nearly a year in visiting its memorable places. It was in the early days of August, 1859, that she landed at Athens; in the early days of June, 1860, she arrived at Venice. In the interval she had visited Nauplia, Argos, and Corinth; had sailed amongst the beautiful islands of the blue Ægean; had wandered in the classic vale of Eurotas, and amongst the ruins of Sparta; had traversed Thessaly, and surveyed the famous Pass where Leonidas and his warriors stood at bay against the hosts of Persia; had mused in the oracular shades of Delphi and gazed at the haunted peak of Parnassus, and looked upon all that remains of hundred-gated Thebes. It is impossible for us to follow in all this extended circuit, and over ground so rich in tradition and association. Wherever she went she carried the great gift of a refined taste and a cultivated mind, so that she was always in full accord with the scene, could appreciate its character, and recall whatever was memorable about it. It is only thus that travel can be made profitable, or that a genuine enjoyment can be derived from it; just as it is only an harmonious nature that feels the full charm of music.

There are delightful pages in Miss Bremer's "Greece

[Pg 180]

and the Greeks"; the keen pleasure she felt in the classic and lovely scenes around her she knows how to communicate to her readers; her literary skill puts them before us in all their freshness of colour and purity of atmosphere. Let us take a picture from Naxos, the island consecrated by the lovely legend of Ariadne; it shall be a landscape fit to inspire a poet's song:—

"Villa Somariva is situated on the slope of a mountain, or on one of the many terraces which are formed from the slopes. Behind the villa lies, somewhat higher up the mountain, a little village of white-washed, small, den-like houses, and a yet whiter church; and still higher up than the village, a square tower—Pyrgos—in the style of the Middle Ages. Below, and on both sides of our villa, spread out extensive grounds, consisting of private gardens and groves, separated from each other by two walls, almost concealed from the eye by the number of trees and bushes which grow there in a state of nature and with all its luxuriance. Vines clamber up into the lofty olive trees, and fall down again in light green festoons, heavy with grapes, which wave in the wind. Slender cypresses rise up from amidst brightly verdant groves of orange, fig, pomegranate, plum, and peach trees. Tall mulberry trees,

umbrageous planes, and ash trees glance down upon thickets and hedges of blossoming myrtles, oleanders, and the aguus cactus. From amidst this garden-paradise, which occupies the whole higher portion of the entire extent of the valley, rise here and there white villas, with ornaments upon their roofs and balconies, with small towers, which show a mediæval Venetian origin. Around the valley ascend mountains in a wide circuit, their slopes covered with shadowy olive woods, and cultivated almost to their summits, which are rounded and not very high.

These larger villages, with their churches, and half a dozen lesser homesteads, are situated on the terraces of the hills, surrounded by cultivated fields and olive groves. All these houses are of stone, and white-washed, and all approach the square or dice-like form. From our windows and balconies which face the west, we can overlook almost the whole of this extensive valley, and beyond a depression in its ring of mountains, we see the white-grey marble tympanum of Paros, with its two sister cupolas, surrounded by that clear blue vapour which makes it apparent that the sea lies between them and our island. On the side opposite to the softly-rounded crown of Paros shines out the interior summit of Naxos, high above the mountain of Melanès, a giant head upon giant shoulders, which are called Bolibay, and have a fantastic appearance.