5.5

Median-1

hour 12.5

32 1/2 minutes 7 1 hour

plus 16

45

minutes

8.5

1 1/2

hours 17

45

minutes

8.5

2

hours 18

3

1/2

hours 19.5

3

1/2

hours 19.5

*When an interval was given as an estimate, the mid-point was tabulated, e. g., 22 1/2 minutes for 20 to 25 minutes.

Notes

1. (E) is used for Eagles; (R) for Rattlers

Reference

Mann, H. B., and Whitney, D. R. A test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Annals

of Mathematical Statistics, 1947, 18, 50-60.

[p. 117] CHAPTER 6

Intergroup Relations: Assessment of In-Group Functioning and Negative Attitudes Toward the Out-Group

In order to insure validity of findings and to increase their precision, the plan of this experiment on intergroup relations specified that different methods of data collection would be used and the results checked against each other (Chapter 2). On the other hand, it was noted that excessive interruption of the interaction processes would result in destroying the main focus of study, viz., the flow of interaction within groups and between groups under varying conditions. Therefore, it was necessary to exercise great restraint in introducing special measurement techniques and experimental units to cross-check the observational data.

At the end of Stage 2, special methods were utilized to check observations related to the main hypotheses for the friction phase of intergroup relations. In addition to sociometric techniques, two experimental units were introduced to tap the subjects' attitudes toward their respective in-groups and the out-group. The results of these units are presented in this chapter, along with additional observational data pertaining to the various hypotheses for Stage 2. These results are not intended to test any separate hypotheses, but to provide further evidence to be evaluated in conjunction with the observational data.

Section A summarizes the effects of intergroup friction on in-group functioning, while the following sections deal with end-products of intergroup friction and conflict, and their assessment through judgmental reactions.

A

Intergroup Friction and In-Group Functioning

The study of in-group structure and functioning was not confined to the first stage of the experiment, which was devoted to experimental formation of in-groups. Several of the hypotheses for Stage 2 specifically concern the effects of intergroup relations (friction, in this case) on in-group structure and functioning. Some [p. 118] consequential effects to the respective in-groups were pointed out in the summary of interaction in the last chapter. Further data will be summarized here. Throughout the experiment the effort was made whenever possible to obtain data by as many methods as feasible without disrupting the ongoing interaction. Checking results obtained by several methods (e. g., observational, sociometric, ratings, judgments of the subjects) leads to confidence in the reliability and validity of the conclusions reached. In considering the hypotheses and data concerning in-group relations in Stage 2, it was necessary to rely heavily on observational data. The more precise techniques of data collection (viz., stereotype ratings and laboratory type judgments) were used for testing the validity of observational findings concerning the negative attitudes (see section B, this chapter).

Because of space limitations, the observational data of this experiment were given in summary form. The danger of selectivity in observation and in reporting observational data is not surmounted by piling example on example. The illustrations chosen are representative of the many available. The conclusions drawn from them are justified by available evidence. They are intended to be suggestive for future research in which observational methods are supplemented increasingly by other more precise techniques of data collection.

At the end of Stage 2, the Rattlers and Eagles were both clearly structured, closely knit in-groups. This is revealed in observational data, observers' ratings, and in sociometric choices obtained at this time from each member individually by the participant observer of his respective group (who appeared as counselor to the subjects).

1. Testing in Terms of Sociometric Indices

The most general criterion on the sociometric questionnaire specified that friendship choices should be made from the entire camp. Table 1 presents the resulting choices for this criterion by members of the Rattler and Eagle groups. In spite of the fact that choices of out-group members were forced somewhat by the manner in which this item was presented, the proportion of choices of in-group members in both groups was approximately 93 per cent, [p.

119] and the differences between choices of in-group members and out-group members are too large to be attributed to chance.

Table 1

Friendship Choices of In-group and Out-group Members

By Rattlers and Eagles

End Stage 2

Rattlers

Eagles

Choices of

f

%

f

%

In-group members

73

93.6

62

92.5

Out-group members

5

6.4

5

7.5

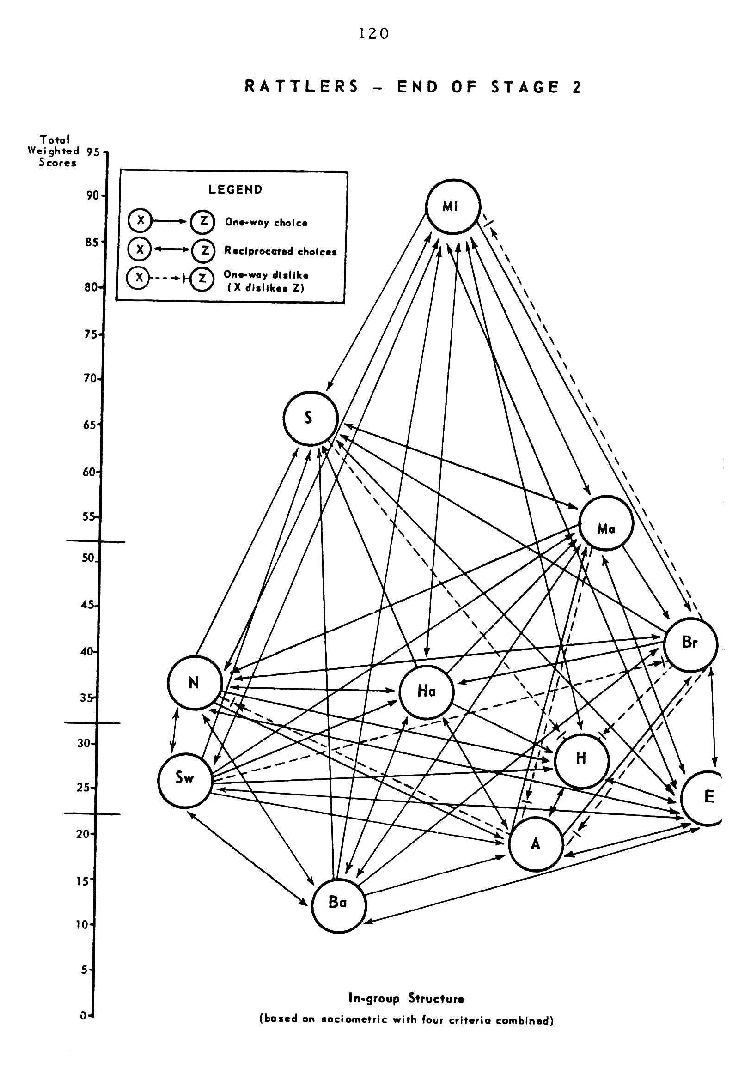

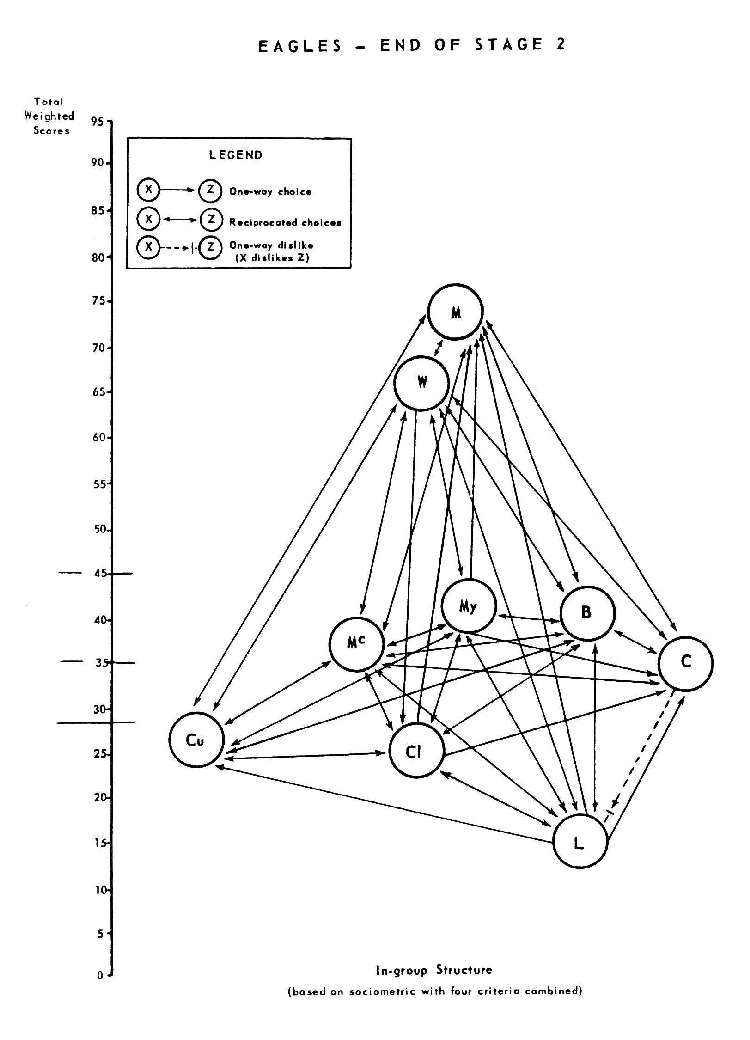

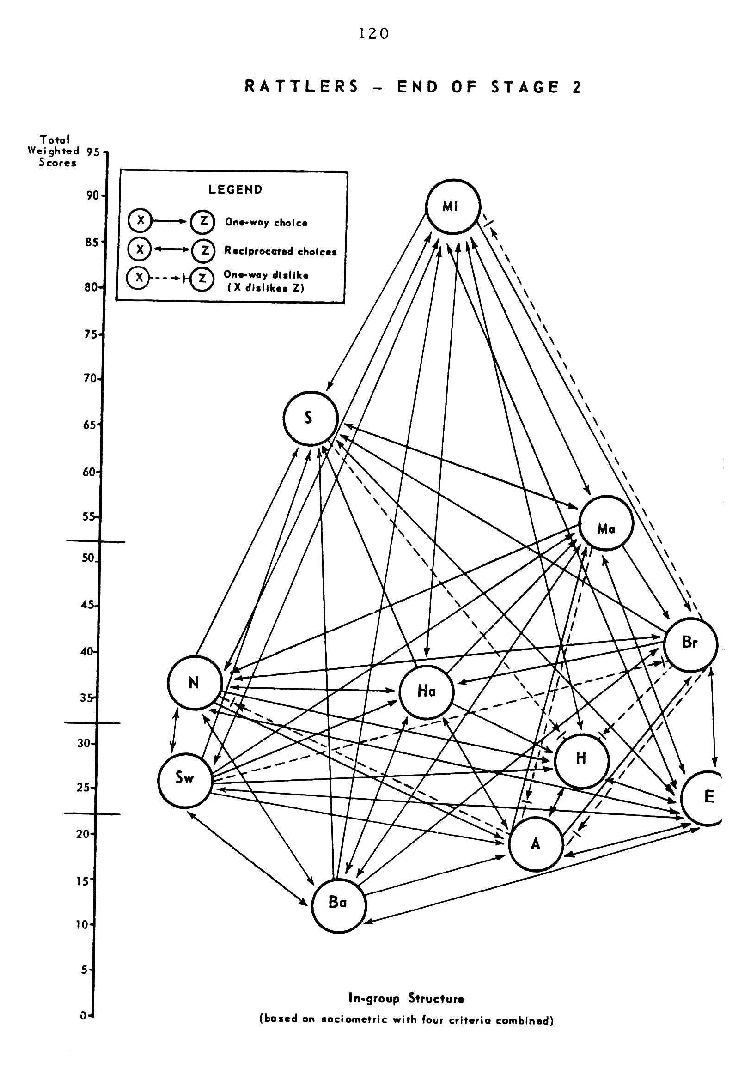

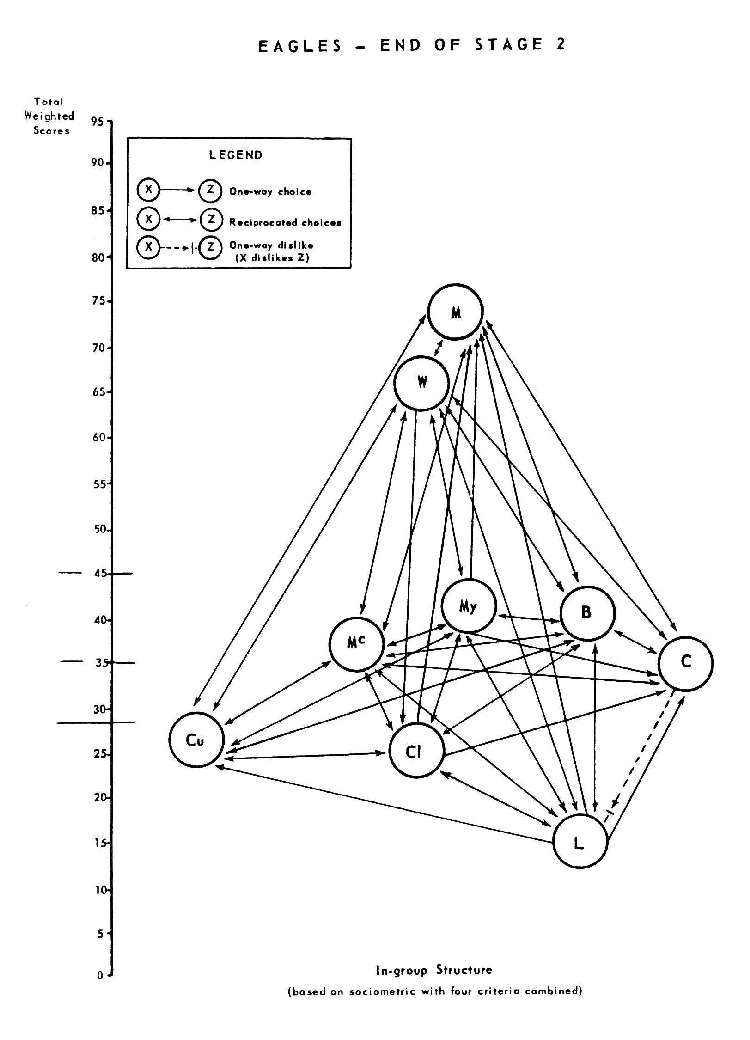

Sociograms were constructed for the Rattlers and Eagles using total score on 4 criteria, as a basis for placement of members (see accompanying sociograms). The score on each criterion was the total of weighted choices, first choices receiving a weight of 4, second choices of 3, third choices of 2, and those thereafter a weight of 1. The choice network was based on the most general criterion (friendship); and rejections were obtained from an item included in the interview, but not used as a criterion in computing total scores. The lines on the ordinates of the sociograms represent Q1, Q2, and Q3 of these ranks in ascending order, the lowest line being Q1.

[p. 120]

[p. 121]

Several discrepancies in ratings of group members based [p. 122] on the various criteria were noted. Two of these criteria were concerned with friendship choices (one general, one more specific), and two were concerned with initiative displayed by various members. It is significant that the scores obtained for these two kinds of choice were widely disparate in several cases.

For example, Everett (R) ranked second on the friendship criteria but only ninth (out of 11) on the initiative criteria. Craig (E) ranked seventh on the friendship criteria, but fourth on the initiative criteria, as did Hill (R).

Since observers' ratings were made more on the basis of effective initiative than on popularity, it is interesting to compare the status ratings of observers and ranks in total sociometric score (4 criteria). As Table 2 indicates, the rank order correlation for these two rating measures is significant and high. Observers undoubtedly gave greater weight to effective initiative than did the combined sociometric scores. This greater weight given to effective initiative in observer status ratings is revealed in cases of discrepancy between sociometric ranks and observer ratings. For example, Brown (R) ranks fourth in sociometric score, but only eighth in observer's ratings. In this case, the sociometric score as computed from choices does not reveal what the observer knew, and what was also revealed during the sociometric interviews. Although Brown received only one rejection from his group, he was mentioned by six members (more than any other member) as the member who would stand in the way of what most of the group wanted to do. To take another example, Bryan (E) ranked fourth in sociometric score and eighth in observer's ratings. In this case, nothing in the sociometric interview revealed, or could reveal, that Bryan was frightened of physical conflict and that during the closing days of Stage 2 he withdrew from interaction altogether on several occasions (even hiding in the bushes). For this reason, he was rated near the bottom of the group by the observer at this time (in terms of effective initiative and influence in the group). On the other hand, the observer noted that since many eagles were frightened of the Rattlers, they did not (excepting Mason, the leader) impose sanctions because of Bryan's behavior. He participated effectively when physical contact with the out-group was not in the picture. Nevertheless, Bryan had very little influence in the group at the end of Stage 2. Such cases il ustrate some difficulties in interpreting sociometric scores based on choice, and point to serious problems of validity when sociometrics are used apart from concrete observational material.

[p. 123] Table 2

Comparison of Ranks in Sociometric Scores and Status Ratings

By Participant Observers of Rattler and Eagle Groups

End of Stage 2

Rho

t

p

Rattlers

.70

2.94

<.001

Eagles

.731

2.83

<.013

2. Testing in Terms of Observational Data

Three of the hypotheses for Stage 2 are concerned with in-group functioning. Data pertinent to them is summarized below.

Hypothesis 2, Stage 2

The course of relations between two groups which are in a state of competition and frustration will tend to produce an increase in in-group solidarity.

Observational data supports this hypothesis with the qualification that in several instances defeat in a contest with the rival group brought temporarily increased internal friction in its wake. This was noted in the Rattler group (Day 3) when they lost the second basebal game.

Disruptive tendencies within the group reached their peak when Brown and Allen wrote letters that afternoon wanting to go home, thus threatening to leave the group. Solidarity was achieved shortly afterward through the integrative leadership of Mills, whose joking about these events led the boys to tear up their letters amid rejoicing by al members.

Similar signs of temporary disorganization followed the first tug-of-war, when the downhearted Eagles stared loss of [p. 124] the tournament in the face. In this case, Myers, Clark, and McGraw took the optimistic view that they had to plan tactics which would defeat the Rattlers.

After the group joined whole-heartedly in burning the Rattler flag, this view was accepted by the leader as well, and considerable hope was seen for the next day.

A somewhat similar adaptation to defeat was made by the Rattlers at the end of the tournament. In this important instance, group action in raiding the out-group was agreed upon right after defeat, sanctioned and planned by the leader and lieutenants, and was executed soon afterward. The aftermath was self-glorification with reference to the group and all its members. The next morning, when Mills "roughed up" several group members, not one tried to challenge his prerogatives, although any one of them could have whipped him easily. (It should be noted here that the Rattler leader, Mills, was one of the smallest boys in size.) The rest of that day was spent in highly congenial play in which Mills made special efforts to involve the low status members and succeeded in effecting their active participation.

It should be emphasized that the temporary disruptive tendencies following defeat illustrated above did not follow loss of every contest. Some defeats were accepted with remarkably little concern or depression, either because the group in question (both Rattler and Eagle) had decided prior to the event that they probably would not win it or because they felt they did not have to win that particular event to win the tournament.

In instances where temporary disorganization did follow defeat (above), heightened solidarity within the group was achieved through united cooperative action by the in-group against the out-group, and this is in line with the above hypothesis. It should be noted and emphasized that the aggressive actions toward the out-group which followed frustration of group efforts experienced in common by in-group members were taken after they were sanctioned by the leaders (Mills or Mason, the leaders of the Rattlers and Eagles respectively). These aggressive actions were sometimes suggested by high status members (notably Simpson and Mills in the Rattlers and Mason in the Eagles), and sometimes suggested by low status members (e. g., Everett in the Rattlers, and Lane in the Eagles). in no instance did the in-groups engage groups in aggressive action toward the out-group if this had [p. 125] not been approved by the leaders of the respective groups. Other evidence supporting this hypothesis as stated is the recurring glorification of the in-group, recounting of feats and accomplishments of individual members, support and approval given low status members, support given the leader, and intensified claims on areas appropriated as belonging to the group.

The Eagles bragged to each other that they were "good sports" who did their best and who prayed and didn't curse. Later they refrained from bragging in the presence of the out-group since this was agreed to bring bad luck. The Rattlers were constantly telling each other, and all within hearing distance, that they were brave, winners, not quitters, tough, and (naturally) good sports.

After the contests and raids, stories were told over and over of the accomplishments of this person and that person, blisters acquired in the tug-of-war were compared both in winning and losing groups, and these tales of individual feats grew with each telling. (The dramatic reversal by the Eagles of their role in the last raid was noted in the account of that event in Chapter 5).

Brown (R) revealed special gifts for recounting such episodes.

During Stage 2, Lane (low status E) was praised for his playing for the first time (by Mason).

Lane became more active in in-group affairs and said they must not swim so much in order to save their strength for the tournament, even though he had earlier been a constant agitator to go swimming at every possible moment. Approval was also given to low status Rattlers during games. After the big raid in which Mason (E) had accused several Eagles of being "yellow-bellied" and cowards, he "covered up" for them completely in telling staff of the events. No mention was made of any defection; all Eagles were made to appear heroic.

The leaders (Mills and Mason) were supported by group opinion consistently, especially after the first day or so when Mason was effectively extending his leadership in baseball (elected) to al areas of group life. Mills was supported by the group even during games when he interfered in decisions made by Simpson (baseball captain); and on one occasion he took Simpson out as pitcher and put in another member in his place.

[p. 126] At the end of Stage 1, we mentioned the increased concern of the in-groups over places appropriated as "theirs." Swift (R) even went so far as to object, when he saw fishermen near their swimming hole, that they had no business taking "our fish." The Rattlers talked, near the end of Stage 2, of putting signs on all of "their" places, including the ball diamond and Stone Corral (which was a part of Robbers Cave). The Eagles were extremely concerned over the fact that the Rattlers went to their hideout on the day after the big raid, and claimed they could detect changes there which did not actually exist.

Hypothesis 3, Stage 2

Functional relations between groups which are of consequence to the groups in question will tend to bring about changes in the pattern of relations within the in-groups involved.

The most striking change in relationships within the in-groups as a consequence of the particular functional relationship between them (rivalry and friction) was in the Eagle group. At the end of Stage 1, Craig was acknowledged leader of the Eagles. Mason was elected captain of the baseball team (only) with Craig nominating and backing him. Even after this, Craig informed Mason that he could not play bal if he didn't have the Eagle insignia stencilled on his T-shirt, and Mason submitted to this after some argument. From the first day of the tournament, however, Mason began to extend his leadership to all group activities, while Craig lost ground throughout Stage 2, being in the middle of the hierarchy by the end (fifth in rank). Some of the incidents revealing this alteration in the Eagles' status structure are mentioned in the summary of interaction presented in the last chapter.

Mason took the group goal of winning the tournament very seriously, giving talks on how to keep from getting rattled, threatening to beat up everyone if they didn't try harder, lecturing on how to win after the first loss in baseball. Although he had not shown interest in keeping the cabin clean before the tournament, he organized cabin cleaning details, and struck Lane (low status) for not helping pick up papers. He had praised Lane's playing in baseball earlier, and the combined effect of Mason's attention was that Lane saw the necessity of reducing the groups' swimming time to "save our strength" - for him a sacrificial act. [p. 127] When captains for the tug-of-war were called, Mason stepped forward, although he had been elected only as basebal captain, and there was no discussion on the point. When the Eagles burned the Rattler flag, Lane first directed attention to it, but Mason took the initial action in trying to tear it up.

Rather convincing evidence of Mason's leadership followed the second tug-of-war, which ended in a tie. Estimates of the time consumed were first obtained individually for each boy, as reported in the last chapter. Subsequently, the boys were asked in a group how long they thought it lasted. Every single Eagle agreed with Mason' s estimate of 45 minutes, although only one other boy had made previously an estimate that high individually.

Craig allowed leadership of the Eagles to slip through his fingers by submitting to Mason' a decisions, perhaps in part because he recognized Mason's superiority as an athlete. (Mills in the Rattler group was not as good a bal player as a few other members; nevertheless he kept control of the group's progress even during baseball games. ) However, Craig fell as far as he did in the status hierarchy because of his defection at several critical points during the tournament. When the group was losing the first tug-of-war, Craig simply walked away from the rope before the contest was over. Afterward he said the Eagles were already beaten in the tournament, and tried to blame others for the tug-of-war loss. However, the Eagles blamed Craig for the loss. When he walked away after the Eagles' loss in tent pitching, the comment was: "He's quit us again. " Craig pretended to be asleep during the first Rattler raid, and kept in the background during the second.

Another shift in the Eagle group which accompanied Mason's rise to the leadership position was Wilson's increasing importance in the group. From a position in the middle of the group's hierarchy (fifth) at the end of Stage 1, Wilson rose to become Mason's lieutenant through his effective playing in sports, his concern with maintaining joint efforts to win the tournament, his support of Mason's decisions. Mason chose Wilson as pitcher in preference to Craig during the first baseball game, and the two figured together in most of the group efforts and activities throughout Stage 2.

The most pronounced changes in the pattern of status relations in the Rattler group during intergroup competition were in [p. 128] the cases of Allen and Brown. After the second baseball game, which the Rattlers lost, Allen was accused of not contributing to the game. He, in turn, accused Martin (higher status) of bragging; but Martin was supported by the other members in the argument. The group members were ruthless in denouncing Allen who cried, wanted to go home, and was talked out of it by Mills (leader). After this, Allen was ignored a good deal, was not chosen to play on the team, and fell from a middle status level to the bottom. Mills'

friendship was his chief tie with the group.

Brown, the largest Rattler, slowly slipped downward in the status structure during Stage 2 until just before the second raid on the Eagles. Because of a pronounced tendency to rough up the smaller boys, Brown was subject to group sanctions and fell to the bottom level of the group.

During the raid his size so impressed the Eagles that he became something of a hero of that event to the Rattlers, and had attentive audiences of smaller boys in recounting his feats.

Intergroup conflict was the medium by which Brown regained a position higher in the group at the end of Stage 2, after having slipped to the bottom level.

Thus, changes in the pattern of relations within the in-groups occurred during Stage 2. These changes are related to the altered contributions of the various members to group activities and efforts as the in-group functioned in a competitive and mutually antagonistic relationship with another group.

Hypothesis 4, Stage 2

Low status members will tend to exert greater efforts which will be revealed in more intense forms of overt aggression and verbal expressions against the out-group as a means of improving their status within the in-group.

The observations relevant to this hypothesis are inconclusive.

As noted in Chapter 2, this hypothesis was not intended to imply that high status members will not initiate and actively participate in conflict with the out-group. In line with one of the major tenets of Groups in Harmony and Tension (1953), its implication should be that intergroup behavior of members consists mainly in participation in the trends of one's group in relation to other groups. Since low status members would be highly motivated to [p. 129] improve their status, it seemed a reasonable hypothesis that they might do so through active participation in the trend of group antagonism and conflict toward the out-group. On the other hand, the establishment and responsibility for such a trend in intergroup affairs rests heavily with the high status members, as does responsibility for sanctioning and conducting affairs strictly within the group. If an upper status member, even the leader, stands in the way of an unmistakable trend in intergroup affairs, he is subject to loss of his standing in the group. This is precisely what happened to Craig, the erstwhile Eagle leader, in the present study. He did not enter into the tournament with sufficiently wholehearted identification with the group's efforts to win; he even walked out on them at critical points when they were losing and "played possum" to avoid conflict (raid) with the out-group.

In view of the necessity to clarify the intent and implications of this hypothesis, it should probably be re-formulated along the following lines: Aggressive behavior and verbal expression against the out-group in line with the trend of intergroup conflict sanctioned by high status members will be exhibited by low status members as a means of improving their status within the group.

This hypothesis could be tested empirically by comparing the reactions of low status members toward the out-group (a) when in the presence of in-group members high in status and (b) when high status members of their in-group are not present. Since the primary concern of Stage 2 in this present experiment was the end products of intergroup friction, this empirical test relating to the behavior of in-group members was not made. As stated in Chapter 2, it was necessary to limit such devices in the present study in order that the interaction processes within groups and between groups would not be complicated by excessive intervention by experimenters. The test situations and more precise methods of measurement which were used during Stage 2 were all devoted to tapping the end products of intergroup friction.

Observational data bearing on this hypothesis cannot be crucial without an empirical test such as that suggested above. The data available are not contradictory of the hypothesis as modified. One consistent finding supports it, namely, that in those instances in which low status members initiated aggressive acts directed toward the out-group, group action followed when the suggestion was approved or taken over entirely by high status members, and [p. 130]

particularly the leader. Conversely there were instances of suggested aggressive action toward the out-group initiated by low status members (and even upper status members) which was not carried out because the leader did not assent to it. The number of raids suggested by various group members far exceeded the number actually carried out. In every case the leader decided on the major details of the raid. Mills set the time for both of the Rattler raids, and Mason (who was the moving force in making the suggestion and in its execution) managed the Eagles'

morning raid on the Rattler cabin, even though Cutler (low status) led the way to the cabin after the decision was reached.

B

Verification of Observational Findings Concerning Intergroup Friction Through Laboratory-type Tasks:

Stereotype Ratings and Performance Estimates

In this stage of negative intergroup relations, Hypothesis 1, Stage 2 is crucial: In the course of competition and frustrating relations between two groups, unfavorable stereotypes will come into use in relation to the out-group and its members and will be standardized in time, placing the out-group at a certain social distance (proportional to the degree of negative relations between groups).

This hypothesis goes to the core of issues concerning the formation and standardization of prejudice of social distance scales in relation to out-groups that prevail in actual social life.

The main events between groups in this stage were manifested through rivalry and actual conflict. Our emphasis in formulation of the crucial hypothesis was on end products in the form of standardized norms relating to the out-group, rather than on specific events revealing conflict, fights, and rivalry. If negative functional relations between groups are more than momentary affairs and give rise repeatedly to fights and hurling of derogatory terms, the end products will be standardized generalizations concerning the out-group which are expressed in the form of unfavorable p. 131] stereotypes. These standardizations constitute the basis of the institution of group prejudice or social distance. Once standardized, such institutions crystallized in negative stereotypes outlast the actual state of negative relations, henceforth predisposing in-group members to categorize out-group members in the light of unfavorable generalizations even at times when the acts of out-group members are not of an unfavorable character. Therefore, our emphasis in formulating hypotheses concerning negative relations between groups has been on negative generalizations concerning the out-group, i. e., standardized stereotypes, rather than on a syllabus of behavioral items revealing hostility, aggression, and other expressions of intergroup conflict.

As the account of interaction during Stage 2 indicates (Chapter 5), there were many specific examples of conflict, in which members of the two experimental groups had to be separated, much name-calling of the out-group, much use of derogatory terms and ridicule. Briefly, one end result of competition and rivalry in a series of contests and of situations in which the behavior of one group