Everett Cutler

Hill McGraw

Swift Lane

Barton

Allen

In line with the hypothesis stated in general form in Stage 2, it was predicted that shifts in in-group relationships might occur concomitant with changes of consequence in relations between groups. The most significant of these (according to sociometric indices) is Mason's slip from the leadership position in the Eagles. As elaborated in Chapter 6, Mason came to the leadership position in the Eagle group in the early days of intergroup competition and rivalry in the tournament. He was intensely involved with the group effort to win and identified with its victory.

It was Mason who took the lead in attempting retaliation on the Rattlers for their last raid.

Perhaps this partially explains why Mason resisted the trend in his group toward increased intermingling with the Rattlers near the end of Stage 3. While he became quite friendly with individual Rattlers, he made it known that he preferred that the Eagles do things together and without the Rattlers. Although his status in the Eagle group remained high, he was followed less and less in his separatist preferences.

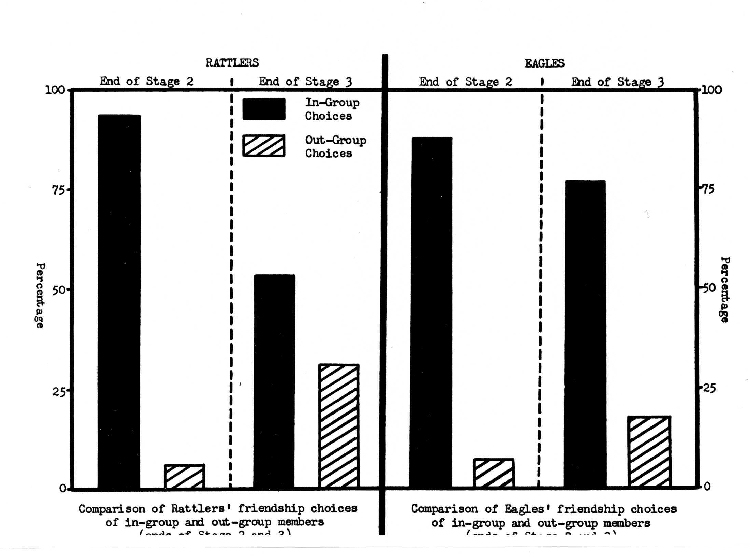

[p. 187] In-group and out-group choices: The data obtained from the most general criterion on the sociometric questionnaire, and through an item on the questionnaire tapping rejections (dislike), provide clear-cut verification of changed attitudes toward the out-group as a consequence of intergroup relationships in a series of situations embodying superordinate goals.

Table 2 gives the choices of in-group and out-group members by Rattlers and Eagles made at the end of Stage 3. As indicated in the table, friendship choices were still predominantly for in-group members.

Table 2

Friendship Choices of In-group and Out-group Members by Rattlers and Eagles End of Stage 3

Rattlers Eagles

f % f %

In-group choices 63 63.6 41 76.8

Out-group choices 36 36.4 15 23.2

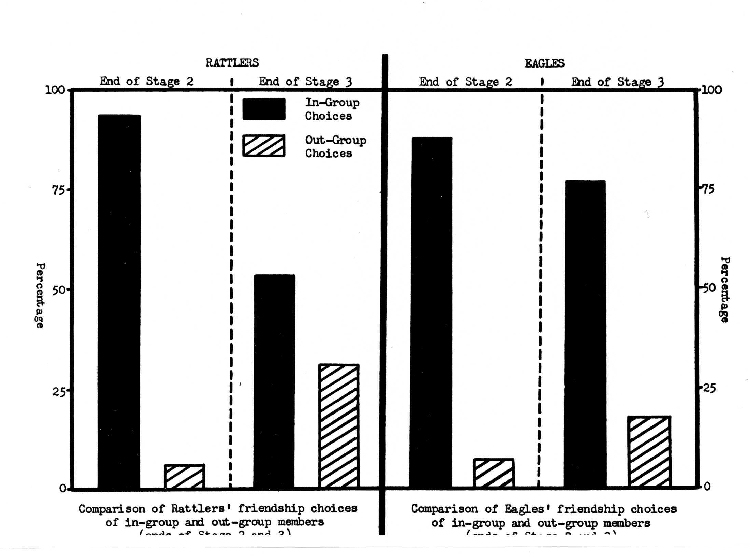

However when the choices of out-group members at the end of Stage 3 are compared with those at the end of Stage 2, a substantial and significant increase is found for both groups. This comparison is made in graphic form in the figure on the next page.

At the end of Stage 2, only 6.4 per cent of the Rattlers' choices were for Eagles; but by the end of Stage 3, 36.4 per cent of their total friendship choices were for Eagles. In the Eagle group, the proportion of choices for the out -group (Rattlers) shifted from 7.5 per cent at the end of Stage 2 to 23.2 per cent [p. 188] at the end of Stage 3.

Concomitant with the increased tendency to choose out-group members as friends there was a decreased tendency to reject members of the out-group as persons most disliked. In the Rattler group, 75 per cent of the rejections at the end of Stage 2 were of Eagles; however by the end of Stage 3, only 15 per cent of their rejections were of Eagles. Similarly, in the Eagle group, 95

per cent of their rejections at the end of Stage 2 were Rattlers, but the proportion of rejections directed at out-group members decreased to 47.1 per cent at the end of Stage 3.

Table 3 compares the changes toward increased choice of out-group members from Stage 2 to the end of Stage 3 and the changes toward decreased rejection of out-group members for both groups.

Table 3

Comparison of Differences in Friendship Choices and in Rejections of Out-group Members at the end of Stage 2 and at the end of Stage 3

Rattlers Eagles

Difference between: chi-square p chi-square p Out-group choices 21.950 <.001 4.050 <.05

Stage 2 and Stage 3

Out-group rejections 7.251 <.01 3.703 Approx. 05

Stage 2 and Stage 3

In the Rattler group, the increase in out-group choices from the end of Stage 2 to the end of Stage 3 is significant at less than .001 level (McNemar test). The decrease in rejection of outgroup members from Stage 2 to the end of Stage 3 is significant at less than the .01 level. The observational data revealed some divergence among members of the Eagle group in attitudes toward the out-group. As might be expected, the differences between out-group choices at the end of Stage 2 and at the end of Stage 3 were slightly less than for Rattlers and significant at

[p. 189]

[p. 190] lower levels.

These data obtained through sociometric techniques constitute, therefore, clear-cut verification of observational findings that when the two hostile out-groups interacted repeatedly in situations embodying goals superordinate to both, the prevailing tendency in both groups was to intermingle with the other, to have increasingly friendly associations with out-group members, and friendly attitudes toward them.

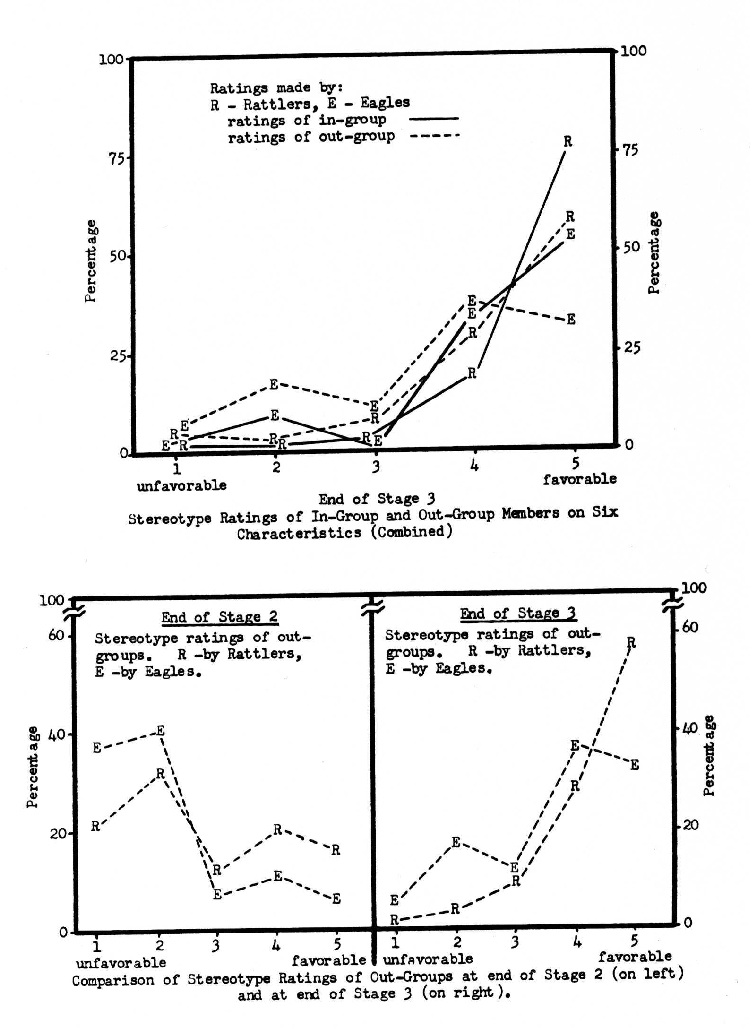

3. Verification of Effects of a Series of Superordinate Goals on Attitudes Toward the Outgroup Through Stereotype

Ratings

As a result of the series of situations embodying superordinate goals in Stage 3 and the interdependent interaction between the hitherto antagonistic out-groups, the two groups engaged in a greater variety of activities together and with increasing freedom. The observations during Stage 3 revealed sharp decrease in the standardized name-calling and derogation of the out-group which had become so familiar during the closing days of Stage 2

and the contact situations without superordinate goals early in Stage 3. In addition, there was less of the blatant glorification of the in-group and bragging on its accomplishments than during the days of rivalry in Stage 2. These observational data were believed to imply changes in attitudes toward the out-group in a more favorable direction, weakening of negative stereotypes of the out-group, and shifts in conception of the in-group as well.

The validity of these observational findings was checked at the end of Stage 3 through ratings by both groups of their in-group and the out-group on the stereotypes which had been standardized in Stage 2. It is significant that when it was announced that the ratings were to be made again, several boys remarked that they were glad, because they had changed their minds since the last ratings.

At the end of Stage 3, the procedures utilized for tapping stereotypes at the end of Stage 2

(intergroup friction) were repeated (see Chapter 6). The second ratings of in-group and outgroup on stereotypes which had been used by subjects during [p. 191] Stage 2 were obtained in order to compare them with those obtained before the series of superordinate goals was introduced in Stage 3 The comparison reveals the effects of interdependence created by compelling goals superordinate to both groups and of the subsequent cooperation between groups. The data to be presented here, therefore, will constitute additional evidence for the verification of the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 a, Stage 2

Cooperation between groups necessitated by a series of situations embodying superordinate goals will have a cumulative effect in the direction of reduction of existing tension between them.

Observational and sociometric data relevant to this hypothesis were summarized earlier in this chapter.

Table 4 shows ratings of out-group members made by Rattlers and Eagles at the end of Stage 2 (friction) and at the end of Stage 3.

Table 4

Stereotype Ratings of the Out-group on Six Characteristics by Members of Rattler and Eagle Groups at the End of Stage 2 (Friction) and Stage 3 (Integration) Category Rattlers' Ratings of Eagles Eagles' Ratings of Rattlers

Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 2

Stage 3

% % %

%

1.* 21.2 1.5 36.5

5.6

2. 31.8 3.0 40.4

17.0

3. 12.1 9.2 7.7

9.4

4. 19.9 28.7 9.6

35.9

5.** 15.0 57.6 5.8

32.1

Chi-square diff. 44.67 34.51

p <.001 <.001

*Most unfavorable

** Most favorable

[p. 192] A comparison of these data obtained following intergroup friction and following cooperative interaction in situations embodying superordinate goals shows a marked shift in the nature of characteristics attributed to the out-group. At the end of the friction stage ratings of out-group members tended to be unfavorable, but by the end of the integration stage, ratings of out-group members were preponderantly favorable in both groups. At the end of Stage 2, 53

per cent of the ratings made by Rattlers of the Eagles had been unfavorable; but at the end of Stage 3 only 4.5 per cent of these ratings were unfavorable and 86.3 per cent were favorable.

Most ratings of the Rattlers by the Eagles (76.9%) were unfavorable at the end of the friction stage; but by the end of Stage 3 the proportion of unfavorable ratings was reduced to 22.6, and the favorable ratings of Rattlers increased to 68 per cent.

The Eagles' ratings of the Rattlers did not change as much in the favorable direction from conditions of competition to conditions of cooperative interaction as the Rattlers' ratings of the Eagles. However, these shifts in the positive direction from Stage 2 to Stage 3 were significant for both groups (Table 4).

Table 5 presents ratings made of members of the in-group at the end of Stage 2 (friction) and Stage 3 (integration). These results suggest that changes in the functional relations between groups tend to produce changes in the conceptions of the in-group.The ratings of in-group members after cooperation with the out-group were not as favorable as the highly positive ratings of the in-group made after the intense intergroup rivalry of Stage 2 although the trend is not statistically significant. At the end of Stage 3, in-groups were still rated favorably by their own members.

For the Rattler group, the difference in proportions of ratings in the most favorable category at the end of Stage 2 and the end of Stage 3 was 9 per cent, and the proportion of ratings in the middle category increased by 4.5 per cent. In the Eagle group, the proportion of ratings in most favorable category after the cooperative activities with the out-group (Stage 3) was 25.9 per cent less than at the end of Stage 2 (intergroup friction).

The trend toward rating the in-group less favorably was more pronounced in the Eagle group.

This finding is in line with

[p. 193] Table 5

A Comparison of Stereotype Ratings of In-group Members by Rattler and Eagle Groups on Six Characteristics at the Ends of Stage 2 (Friction) and Stage 3 (Integration) Category Rattlers' Ratings of Rattlers Eagles' Ratings of Eagles Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 2 Stage 3

% % % %

1.* 0 0 0 0

2. 0 0 3.8 9.2

3. 0 4.5 1.9 3.8

4. 13.7 18.2 14.7 33.3

5.** 86.3 77.3 79.6 53.7

Chi-square diff. 3. 546 7.501

p .30 .10-.11

* Most unfavorable

** Most favorable

observational data indicating that the Eagle group revealed shifts in status structure, during the interaction in cooperative activities with the Rattlers during Stage 3. Briefly, most of the Eagles were drawn into the compelling interdependence between groups in Stage 3 and all participated in cooperative intergroup activities. A few Eagles, including the leader during Stage 2, entered into these activities and became friendly with individual members of the Rattler group, but were more tenacious than others in preferring in-group association to contacts with the whole Rattler group. As noted earlier, this state of affairs, in turn, reduced the effectiveness of the Eagle leader, who had achieved his greatest eminence during intergroup rivalry.

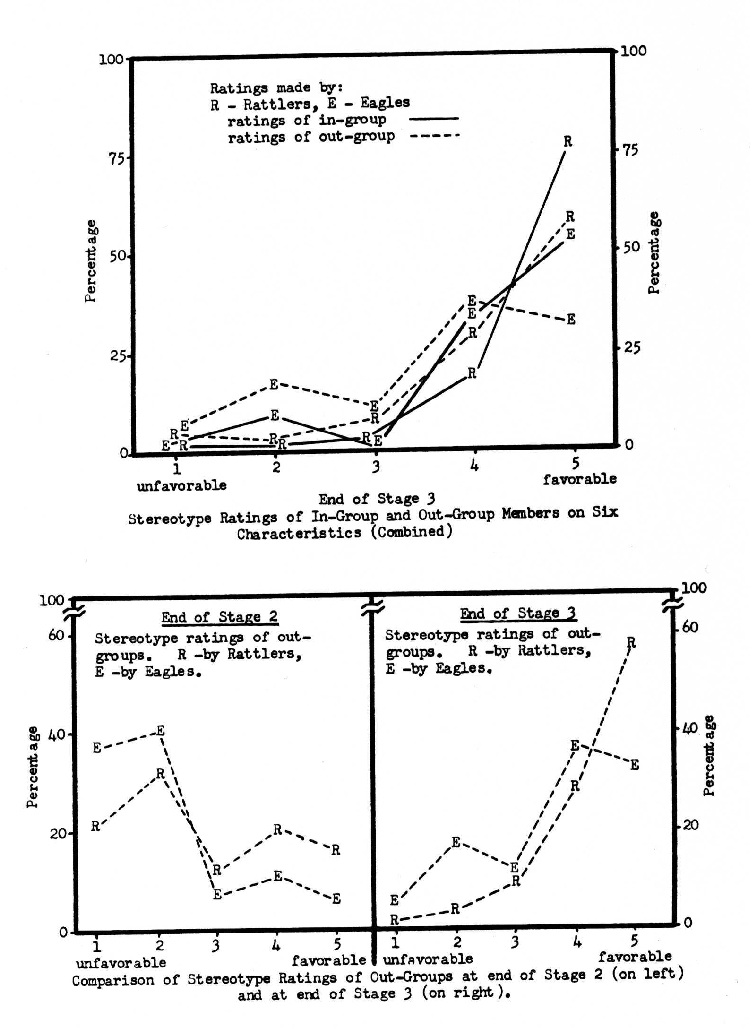

The accompanying figures present a graphic summary of the stereotype ratings of in-group and out-group by the Eagles and Rattlers on the six characteristics (combined) following Stage 2

and Stage 3. At the end of Stage 3, ratings of in-group and out-group members did not differ significantly (p .10).

[p. 194]

[p. 195] Thus, at the end of Stage 3:

(a) Favorable characteristics tended to be attributed to the out-group, in contrast to the predominantly unfavorable picture of the outgroups the end of Stage 2 (friction).

(b) Ratings of both the in-group and the out-group were favorable and did not differ significantly.

(c) The relative frequency of favorable ratings made in relation to in-group members was slightly less than at the end of Stage 2 (friction), particularly in the case of the Eagle group which was undergoing some shifts in in-group structure.

Competition and rivalry between groups in Stage 2 was accompanied by attribution of unfavorable characteristics to the out-group and favorable characteristics to the in-group (Chapter 6). This generalisation takes on added significance when viewed in terms of the backgrounds, personal and socio-cultural, of the two groups of boys. All were normal, well-adjusted boys who enjoyed high and secure status positions both at home and in school. None were problem children who had suffered unusual frustrations and privations. The results indicating the formation of negative stereotypes of the out-group during competitive intergroup relationships cannot be attributed to unusual psychological conditions brought by the boys to the experimental situation. The enthusiastic participation in intergroup competition reflects, of course, the strong emphasis on competition in the larger socio-cultural setting. However, the rise of intergroup hostility and attribution of derogatory labels to the out-group was a development opposite in direction to another important value from the larger setting, namely

"good sportsmanship" on the part of participants in competitive activities.

The observance of norms of social distance between the groups and maintenance of a derogatory picture of the out-group did not decrease until the two groups had interacted in a series of situations embodying superordinate goals. The subsequent cooperation between the groups was accompanied in time by a marked change in the conception of the out-group in the favorable direction.

These results may be taken as further evidence supporting [p. 196] our hypothesis that cooperation between groups as a consequence of interaction in situations embodying superordinate goals has a cumulative effect in the direction of reducing existing tensions between them (Hypothesis 2 a, Stage 3).

The data obtained by tapping judgments concerning the character of one's in-group and of the out-group under conditions of competition and rivalry (Stage 2, see Chapter 6) and conditions leading to cooperative intergroup activity are congruent with observational findings concerning behavior in relation to the in-group and out-group. Together they are presented as a contribution to the study of the formation and change of values or social norms. Specifically, these data confirm the hypotheses concerning conditions conducive to the formation of unfavorable attitudes toward functionally related out-groups and conditions conducive to their change to attitudes of cooperation and friendship between groups.

[p. 197] CHAPTER 8

Summary and Conclusions

A. The Present Approach

In this book we have presented an experiment on Intergroup relations. The theoretical approach to the problem, the definitions of groups and relations between them, the hypotheses, the selection of subjects, the study design in successive stages, the methods and techniques, and the conclusions to be drawn are closely related. This chapter is a summary statement of these interrelated parts.

The word "group" in the phrase "intergroup relations" is not a superfluous label. If our claim is the study of relations between two or more groups or the investigation of intergroup attitudes, we have to bring into the picture the properties of the groups and the consequences of membership for the individuals in question. Otherwise, whatever we may be studying, we are not, properly speaking, studying intergroup problems.

Accordingly, our first concern was an adequate conception of the key word "group" and clarification of the implications of an individual's membership in groups. A definition of the concept improvised just for the sake of research convenience does not carry us far if we are interested in the validity of our conclusions. The actual properties of groups which brought them to the foreground in the study of serious human problems have to be spelled out.

The task of defining groups and intergroup relations can be carried out only through an interdisciplinary approach. Problems pertaining to groups and their relations are not studied by psychologists alone. They are studied on various levels of analysis by men in different social sciences. In the extensive literature on relations within and between small groups, we found crucial leads for a realistic conception of groups and their relations (Chapter 1).

Abstracting the recurrent properties of actual groups, we attained a definition applicable to small groups of any description. A group is a social unit which consists of a number of individuals who, at a given time, stand in more or less definite

[p. 198] interdependent status and role relationships with one another, and which explicitly or implicitly possesses a set of norms or values regulating the behavior of the individual members, at least in matters of consequence to the group.

Intergroup relations refer to relations between groups thus defined. Intergroup attitudes (such as prejudice) and intergroup behavior (such as discriminatory practice) refer to the attitudes and the behavior manifested by members of groups collectively or individually. The characteristic of an intergroup attitude or an intergroup behavior is that it is related to the individual's membership in a group. In research the relationship between a given attitude and facts pertaining to the individual's role relative to the groups in question has to be made explicit.

Unrepresentative intergroup attitudes and behavior are, to be sure, important psychological facts. But attitude and behavior unrepresentative of a group do not constitute the focal problem of intergroup relations, nor are they the cases which make the study of intergroup relations crucial in human affairs. The central problem of intergroup relations is not primarily the problem of deviate behavior.

In shaping the reciprocal attitudes of members of two groups toward one another, the limiting determinant is the nature of functional relations between the groups. The groups in question may be competing to attain some goal or some vital prize so that the success of one group necessarily means the failure of the other. One group may have claims on another group in the way of managing, controlling or exploiting them, in the way of taking over their actual or assumed rights or possessions. On the other hand, groups may have complementary goals, such that each may attain its goal without hindrance to the achievement of the other and even aiding this achievement.

Even though the nature of relations between groups is the limiting condition, various other factors have to be brought into the picture for an adequate accounting of the resulting intergroup trends and intergroup products (such as norms for positive or negative treatment of the other group, stereotypes of one's own group and the other group, etc.). Among these factors are the kind of leadership, the degree of solidarity, the kind of norms prevailing within each group. Reciprocal intergroup appraisals [p. 199] of their relative strengths and resources, and the intellectual level attained in assessing their worth and rights in relation to others need special mention among these factors. The frustrations, deprivations and the gratifications in the life histories of the individual members also have to be considered.

Theories of intergroup relations which posit single factors (such as the kind of leadership, national character, individual frustrations) as sovereign determinants of intergroup conflict or harmony have, at best, explained only selectively chosen cases.

Of course leadership counts in shaping intergroup behavior, the prevailing norms of social distance count, so do the structure and practices within the groups, and so do the personal frustrations of individual members. But none of these singly determines the trend of intergroup behavior at a given time. They all contribute to the structuring of intergroup behavior, but with different relative weights at different times. Intergroup behavior at a given time can be explained only in terms of the entire frame of reference in which all these various factors function interdependently. This approach, here stated briefly, constituted the starting point of our experiments on intergroup relations. The approach was elaborated fully in our previous work, Groups in Harmony and Tension.

The relative weights of various factors contributing to intergroup trends and practices are not fixed quantities. Their relative importance varies according to the particular set of conditions prevailing at the time. For example, in more or less closed, homogeneous or highly organized groups, and in times of greater stability and little change, the prevailing social distance scale and established practices toward out-group which have been standardized in the past for group members will have greater weight in determining the intergroup behavior of individual members.

But when groups are in greater functional interdependence with each other and during periods of transition and flux, other factors contribute more heavily. In these latter cases, there is a greater discrepancy between expressed attitude and intergroup behavior in different situations, attributable to situational factors, as insistently noted by some leading investigators in this area of research. Alliances and combinations among groups which seem strange bedfellows are not infrequent in the present world of flux and tension.

[p. 200] Because of their influence in social psychology today, two other approaches to intergroup behavior deserve explicit mention. A brief discussion of them will help clarify the conception of the experiment reported in this book.

One of these approaches advances frustration suffered in the life history of the individual as the main causal factor and constructs a whole explanatory edifice for intergroup aggression on this basis. Certainly aggression is one of the possible consequences of frustration experienced by the individual. But, in order that individual frustration may appreciably affect the course of intergroup trends and be conducive to standardization of negative attitudes toward an outgroup, the frustration has to be shared by other group members and perceived as an issue in group interaction. Whether interaction focusses on matters within a group or between groups, group trends and attitudes of members are not crystallized from thin air. The problem of intergroup behavior, we repeat, is not primarily the problem of the behavior of one or a few deviate individuals. The realistic contribution of frustration as a factor can be studied only within the framework of in-group and intergroup relations.

The other important approach to intergroup relations concentrates primarily on processes within the groups in question. It is assumed that measures introduced to increase cooperativeness and harmony within the groups will be conducive to cooperativeness and harmony in intergroup relations. This assumption amounts to extrapolating the properties of in-group relations to intergroup relations, as if in-group norms and practices were commodities easily transferable.

Probably, when friendly relations already prevail between groups, cooperative and harmonious in-group relations do contribute to solutions of joint problems among groups. However, there are numerous cases showing that in-group cooperativeness and harmony may contribute effectively to intergroup competitiveness and conflict when interaction between groups is negative and incompatible.

The important generalization to be drawn is that the properties of intergroup relations cannot be extrapolated either (1) from individual experiences and behavior or (2) from the properties of interaction within groups. The limiting factor bounding intergroup attitudes and behavior is the nature of relations between groups. Demonstration of these generalizations has been one of the primary objectives of our experiment.

[p.201] B. The Experiment

The Design in Successive Stages

Experimental Formation of Groups: In order to deal with the essential characteristics of intergroup relations, one prerequisite was the production of two distinct groups, each with a definite hierarchical structure and a set of norms. The formation of groups whose natural histories could thus be ascertained has a decided advantage for experimental control and exclusion of other influences. Accordingly, Stage l of the experiment was devoted to the formation of autonomous groups under specified conditions. A major precaution during this initial stage was that group formation proceed independently in each group without contacts between them. This separation was necessary to insure that the specified conditions introduced, and not intergroup relations, were the determining factors in group formation.

Independent formation of distinct groups permitted conclusions to be drawn later from observations on the effects of intergroup encounters and engagements upon the group structure.

The distinctive features of our study are Stages 2 and 3 pertaining to intergroup relations. The main objective of the study was to find effective measures for reducing friction between