I’d wanted to dance the classics very much, and though I tried to combine

repertories, it just wasn’t possible. I never had any extra energy or extra

time. There was no other way but to leave. I had to see if I could develop

on my own, if I could be everything I could be as a dancer.

Q: Did you know about Mischa’s plans to defect?

A: I had heard the rumors, but I thought that he wouldn’t.

Q: When did you first see him dance?

A: When the City Ballet was in Leningrad in 1972, I saw him in class

and in a performance of Don Quixote, which was incredibly exciting. It was a matinee day for our company, and I was the only one free. A whole bus

had been chartered to take us to the Kirov school, but I was the only one

on it. I didn’t expect Mischa to be there and had never seen him anyway,

but I knew from his picture who he was. All of a sudden, the pianist in

class started playing the variation from Don Quixote, and Mischa danced it.

It was a real shock to my system. I was scared to death to meet him.

Q: Did he see you perform with the City Ballet?

A: He did, but it’s different; yes, it’s different.

40

Treasures Past and Present

Q: In what ways is Mischa different from the men in the City Ballet?

A: In everything. First of all, he comes from a wholly different

background. He has a Russian temperament, and all the Russians I have

known have been moody. But he is extremely sincere. When we are

working together, Mischa is never, never a bastard. He can be impatient,

or maybe very serious, but he is never rude. If I’m having trouble with

something, we work it out, and though he may make fun of me, he is

never a bitch.

Q: Do the two of you clash onstage or harmonize?

A: I’m a more mild personality, more even. At the beginning, that’s

something you don’t want to accept, that he is more assertive. As yet I

don’t have much point of view about the partnership. The next six months

will be a transition for me, and I’ll have to see how it goes. In Winnipeg

last month, we danced a week of Don Quixote s, which was very difficult for me. It was a combination of the pressure and of just doing Don Quixote over and over. My body felt the effect. Some of the performances I was happy

with—just two—but the others for me were unfulfilling.

Q: What change do you find working with Ballet Theatre and not the

City Ballet?

A: It’s difficult, that’s the difference.

Q: Your last visit here was with the City Ballet last spring. How did

that go?

A: I didn’t enjoy Washington very much. I’m really spoiled, because

I’ve always been surrounded by the most perfect conditions at the New

York State Theater—a fantastic orchestra, a great stage. I’m used to a

theater where I live; it’s my home. At the Kennedy Center the dancers

found the floor too hard, and we didn’t have enough time to rehearse. I

remember a performance of Dances at a Gathering; I love that part very

much, and I didn’t dance it well at all. When you give a bad performance,

there’s no turning back. You want another chance terribly, but you have to

realize that there’s always next time. If you let your disappointment get to

you, it can easily work against you.

Q: How did Mr. Balanchine take the news of your leaving?

A: He was very understanding. He knows that people have to do what

they have to do. And he said that I could come back, “if you want to come

back, if there’s room. . . .”

41

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

Q: What was your farewell with the company?

A: My last performance in New York was in A Midsummer Night’s Dream,

and it was very special for me. It was the last time, perhaps, that I’ll ever

do the pas de deux, which is such a beautiful piece. Personally, it was one

of the best performances for me. I was sad, but I left the company with a

good memory.

October 20, 1974

W

Two Different Worlds Make a Smooth Blend

It was fascinating to see Mikhail Baryshnikov and Fernando Bujones dance

back-to-back during Ballet Theatre’s second program last night in the Ken-

nedy Center Opera House. Each is considered an epitome of excellence,

the finest products of the Russian and American schools, respectively.

Their roles were wildly different—Baryshnikov took the lead in Petipa’s La

Bayadère, while Bujones played the Latin sailor in Robbins’ Fancy Free—yet the differences were ones of syntax and style. Beneath their surfaces, the

works share a common language and ask of their executants a common

understanding.

Thinking back to Bujones in roles of raw bravura, it is easier to see

his distinguishing traits. More meaningful than his elegant grooming is his

quickness of response. Ever since Balanchine redefined the ratio of move-

ment to music, speeding up the action by gearing the gesture with a smaller

rhythmic unit than had previously been observed, dance has been get-

ting faster. Bujones is quick in his viscera. He is always on top of the beat,

which generates excitement, yet I think he loses some flexibility of phrasing

through such precise incisiveness.

Baryshnikov, to the contrary, has a gorgeous musicality. He is a master

of rubato and can modulate a phrase through varying shades of intensity.

Reared in a manner that was rhythmically less exacting, he has an inbred

freedom that allows for spontaneity. One saw this during Bayadère, in the

final solo in the penultimate dance, a passage that he sailed through with

marvelous abandon. Elsewhere, however, he was rather tight and tentative.

Gelsey Kirkland, his partner, still lacks the stature to completely fill her

role; she seems to have too slight a stage presence, and there’s not enough

variety in the way she uses weight.

42

Treasures Past and Present

Some more on Bayadère—Ballet Theatre’s production misses the philo-

sophical point of the piece. Petipa, the choreographer, is idolizing woman

and dehumanizing her at once. To get this multiple effect, the corps of bal-

lerinas who stream onstage at the start, one by one, identically dressed in

tulle, must have the uniform elegance of a string of matched pearls. Indi-

viduality is out, and when a redhead comes onstage (Ruth Mayer, the 13th

woman to appear) to be followed by a blond (Patricia Wesche, the 18th), the

intended effect is largely lost. Wigs, I suppose, are called for.

Bayadère stands for glorious excess, and without the full corps of 32

women, this can hardly be achieved. Ballet Theatre uses 24, but their col-

lective presence is somehow diminished. The music gives the game away,

specifically at the start of the third phrase, when the score slips down to

the minor mode and the 17th woman appears. From this moment, which

breaks the harmonic regularity and broadens the structural scope of the

piece, the women might go on forever. Two dozen, however, can never at-

tain the critical mass that results in theatrical magic.

Baryshnikov last night was curiously unprofessional in a number of

ways. Through Bayadère he wore what appeared to be a gold wedding band,

and he performed the piece, as well, in a tunic that was ripped on its right

side, though basted together just before his solo.

Minkus is a dog of a musician, but the music that serves as the overture

to Bayadère is strongly suggestive of Schumann and by no means boring, like so much of what he usually composed. Orchestral playing last night was

fine, and Akira Endo again led a fine performance.

October 24, 1974

W

Baryshnikov: Eloquent Potential Realized

new york — If there is a more accomplished male than Mikhail Barysh-

nikov in classic dance today, I can’t imagine who he is or what in the world

he is doing.

The American debut of the 26-year-old Latvian-born virtuoso who

recently defected from the Kirov Ballet was sensationally persuasive. As

Albrecht in Giselle, which he performed with the American Ballet Theatre

on Saturday night at Lincoln Center, he danced with a diamond-like bril-

43

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

liance, and when pandemonium erupted at the end of the evening, there

was ample time to wonder what makes him so superlative.

Baryshnikov is physically unassuming. Neither the aristocratic danseur

noble in the mold of Erik Bruhn nor the sexually electric superstar like

Rudolf Nureyev, he is compact and short of stature, while his face is less By-

ronic than boyish and eager.

Nijinsky iconography came quickly to mind while watching him

Saturday night. Like the legendary star of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes,

Baryshnikov has a body that gives little hint of its eloquent potential, of the

theatrical intensity and technical mastery it generates with ease. And surely

like his predecessor, Baryshnikov does amazing things. His secret, I think,

is in the strength of his feet. His elevation is notably fine and exaggerated

in its impact, because Baryshnikov soars with virtually no visible prepara-

tion; he springs upward with effortless elasticity, as if little trampolines

propelled him.

There’s a silken quality to his movement and a strength in its relation

to the space in which it swims. Musically, the dancing is suave; phrases are

long spun and urbane. I imagine that technically there is nothing beyond

his ken. In one of the most remarkable few seconds I have ever seen—

in the second act of Giselle—he skittered across the stage in a series of feath-erweight brisés, beating his feet with a lightning delicacy at the apex of each.

The only comparable dancing I have seen to equal this in sheer bravura was

done by the great Alicia Alonso, also, coincidentally, in the second act of

Giselle.

As an actor Baryshnikov stands at the head of a mime tradition that has

been preserved and passed forward for decades at the Vaganova Academy,

the Kirov-affiliated school in Leningrad. To Western eyes, the dramatic

emphasis might seem needlessly overdrawn. Not much is subtle about this

style of acting, but every gesture is literate and speaks with authority, and

as performed on Saturday, they absorb the eye. Baryshnikov, then, is one

of the great beauties; it will be a pleasure to watch his career evolve and a

privilege to welcome him wherever he may dance.

July 29, 1974

44

Treasures Past and Present

W

A Union of Flawed Convenience

I believe I’m betraying nothing of confidence when I say that Natalia Ma-

karova and Mikhail Baryshnikov bear little love for each other. Some of our

favorite Russians, who, ironically, are the reigning stars of the American

Ballet Theatre, are known to be feline. On occasion, the bitchiness surfaces.

In her enlightening interview with Philip Kadis that appeared on this

page yesterday, Makarova referred to Baryshnikov with delicious con-

descension, covering him richly with false solicitude the way she might

schmear schmalz on fresh black bread.

A lack of rapport was perhaps the most flagrant flaw in last night’s

performance of Giselle, the opening work in the two-week engagement

by the American Ballet Theatre at the Kennedy Center Opera House. It

was danced, for the most part, routinely. Makarova and Baryshnikov both

had splendid moments, but not even their collective gifts could ignite the

performance.

Their partnership onstage is a marriage of convenience. In artistic dis-

positions they are probably too much akin to make a successful pair. The

great collaborations of recent years have been notable fusions of distinct

personalities—Fonteyn and Nureyev, Fracci and Bruhn—and how won-

derfully different they are, yet how smoothly they work together. Both Ma-

karova and Baryshnikov love the spotlight as much as it loves them, chal-

lenging their compatibility.

There was beautiful ensemble work in last night’s Giselle, but it came

from other sources. Marianna Tcherkassky and Fernando Bujones, in the

first act pas de deux, for example, showed an exemplary affinity. They

looked as though they’d danced with each other for ages; they were mu-

tually respectful and instinctively sensitive to each other’s demands. Miss

Tcherkassky’s solo work was lovely as well: she has clarity and daintiness

and, within a small framework, force. Bujones, I felt, was trying too hard.

Most of his dancing was classically elegant and manly in execution, but his

endings were always forced.

Makarova was at her best in her second act solo variation, and ditto

for Baryshnikov. Technically, each passage was superb. If Baryshnikov’s

work seemed far more compelling, it is because he communicates greater

45

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

warmth than Makarova—she is an emotionally chilly dancer—and because

he etches his role with theatrical gestures to telling dramatic effect. He

is one of the age’s most formidable actors as well as a dancer of uncanny

aplomb. As Ballet Theatre’s visit evolves, I am sure we will see him, and

Makarova, too, in situations more comfortable than those they were in last

night.

May 14, 1975

W

Baryshnikov’s Skills Are Akin to Marceau’s

Few careers can compare with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s. Since he defected

from Russia while on tour last year, his ascent has been spectacular in inten-

sity and speed. It has been more than a decade since the world of dance wit-

nessed a star of comparable brilliance; Rudolf Nureyev, like Baryshnikov,

was a product of the Kirov Ballet until he spurned his homeland’s regressive

aesthetics and opted for the freedom of the West.

Baryshnikov, like his colleague, has sought to enlarge the scope of his

style, and last night in the Kennedy Center Opera House, he appeared with

the American Ballet Theatre in a program designed around his versatile

skills.

The chief curiosity of the evening was the American premiere of Leonid

Jacobson’s Vestris, which was made for Baryshnikov for the International

Ballet Competition in Moscow in 1969, and what a curious work it is! A

set of variations in mock-rococo manner, Vestris is a character study of brilliance that ranges through the ages of man.

Framing the work is a courtly processional, danced to a score by Gen-

nadi Banchikov that is full of false deference and gestures of fealty. The sub-

stance of the piece is a sequence of dances that shows the theatrical affects

with a wonderful wit. These depictions—anger, senility, and foppishness

among them—were the stock in trade of the arts of the eighteenth century,

and Jacobson has perceived the essence of their movement with precision.

His dances have a rich imagination, and his use of weight and space and

timing is always telling and often deeply moving. Baryshnikov’s portrayal,

for instance, of an elderly man as he sinks to his death was one of the most

evocative pieces of poetry I could ever hope to see. In its sense of immediate

communication, it reminded me of the art of Marceau, whose sketches of

46

Treasures Past and Present

mortality are akin to Vestris in their artful illusion. Marcel Marceau, indeed, is a worthy comparison, for both he and Baryshnikov have elevated mime

to a level of sublimity.

Baryshnikov’s performance in La Bayadère was also remarkable, though

his dancing was slow to warm. When he found his stride, however, he was

sensationally good; besides his immaculate technique and his high sense of

style, he brought to his dancing a special excitement through the execution

of steps that are particularly his own. These extra embellishments may lie

outside the classical canon, but their dramatic effect is unquestioned.

Bayadère, otherwise, was hardly the performance it should have been.

David Gilbert, the conductor, took tempos that were usually too fast; they

hurried the piece and made it seem superficial, for the pace of the music

never gave the eye a chance to absorb the images of the dance. Alternately,

when the dance should have moved—when Gelsey Kirkland, for example,

wanted a faster tempo in the “Scarf Dance”—Gilbert refused to budge.

The orchestra’s playing, incidentally, was far too often faulty. The musicians

sounded inattentive and inexperienced, and not one performance I have

heard this engagement has been free of careless mistakes.

Baryshnikov’s final appearance was in Le Jeune Homme et la Mort (The

Young Man and Death), with choreography by Roland Petit after a scenario

by Jean Cocteau set to music by Bach. Only the French would hear the ma-

jestic C-Minor Passacaglia as a piece of background music, and Petit’s trash

choreography is in accord with an attitude that trivializes the most serious

subjects.

Baryshnikov’s gifts are wasted on such junk, though his performance

was taut and compelling, a picture of pent-up frustration. As the girl, Bon-

nie Mathis was excellent as well, performing her part with a sexy insinu-

ation. With artists such as these, however, it is a shame for them to spend

their efforts on garbage like Petit’s.

May 21, 1975

.

47

part two

se t t i ng ne w sta nda r ds

:

For Balanchine, if it was ballet, it was always new.

— w. mc n e i l l ow ry, v ic e p r e s i de n t

of t h e f or d f ou n dat ion,

i n i r e m e m b e r b a l a nc h i n e,

b y f r a nc i s m a s on

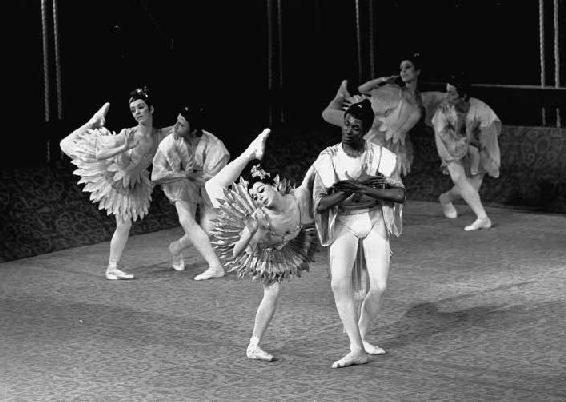

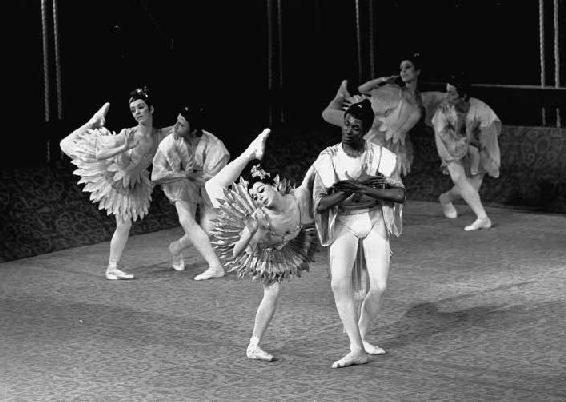

above Allegra Kent and Arthur Mitchell in the New York

City Ballet production of George Balanchine’s Bugaku, 1970.

Photo: Martha Swope / © The New York Public Library.

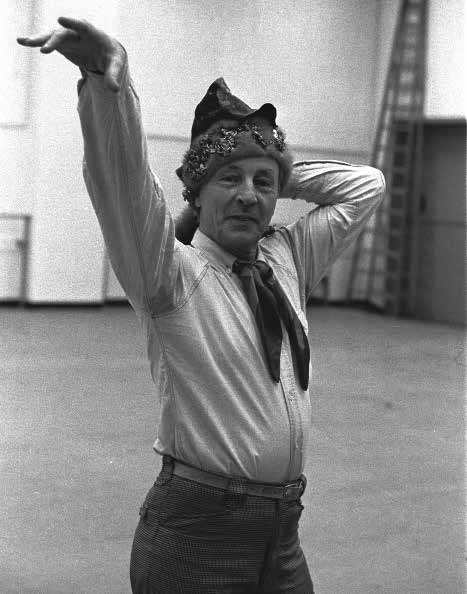

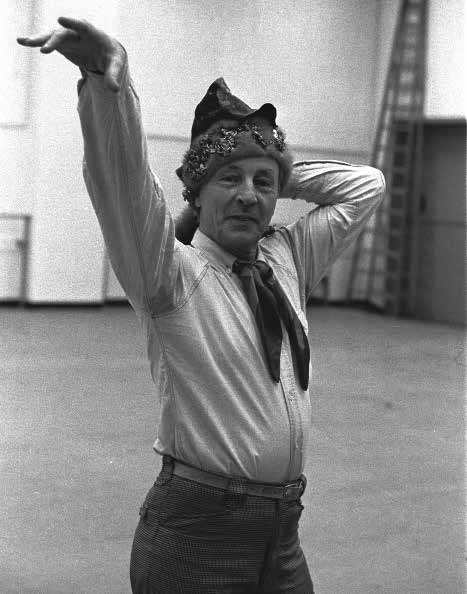

previous George Balanchine in the New York City Ballet rehearsal

room during the costume parade for Balanchine’s Firebird, 1970.

Photo: Martha Swope / © The New York Public Library.

w n e w yor k c i t y ba l l e t w

Why George Balanchine Is Pleased with Himself

new york — Shortly before curtain time one evening last weekend,

George Balanchine walked across the front of the plaza at Lincoln Center,

home of his City Ballet. When he reached the corner of the New York State

Theater, where the company soon would perform, he stopped and turned

toward the play of the fountain and the hundreds of people, theatergoers

and sight-seers alike. With the characteristic funny twitch of the nose and

the quick blink of the eyes that make this greatest of contemporary chore-

ographers seem a cross between a sparrow and a rabbit, he surveyed the

scene for several minutes and then continued to the stage door.

Though there was no way to know what he thought as I observed

him from above, from the State Theater’s outdoor balcony that faces

Philharmonic Hall, Balanchine was lovely and enigmatic. That he felt some

satisfaction, I have no doubt. This season, after all, which resumed in New

York last week after a triumphant two weeks at the Kennedy Center, cel-

ebrates both the 25th year of the City Ballet and its 10th year of residence at

Lincoln Center. No longer a maverick and not yet a matron, the organiza-

tion is our finest purveyor of classical dance. It judiciously guards traditions

even as it creates innovations, and its repertory shows how well this dual

function is filled.

To take just one pair of the pieces that I saw in performance last week-

end: the Duo Concertant, which was made for Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins

and received its premiere during the Stravinsky Festival two years ago, is in

many ways Balanchine’s most sophisticated work.

51

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

Dramatically, it grows ever more refined and compelling. Though only

two dancers perform, they share the stage with the musical soloists, a vio-

linist and pianist. The piece is properly perceived as a quartet; it begins

with the dancers standing behind the piano, listening to the score. Even-

tually they walk to stage left and start to move, doing schematic, angular

movements that look like warm-up exercises at the barre. There are more

purely musical episodes and more sections that are danced, and these latter

segments are brilliantly alive to the music’s implications.

Finally, as the work nears its end, the stage darkens and the principals

are isolated by four shafts of light. After the competitive interplay of much

of the score, the musicians now unite in a calmer colloquy. The dancers

answer this with gestures of equal concord; at the apogee of the piece, the

male bows before his Muse and tenderly kisses her hand, an act that clarifies

the emotional tone of all we saw before.

The Concerto Barocco is less explicit. Made in 1941, it is a model of plotless ballet. It substitutes for narrative a flux of changing qualities. What the

ears hear, the eyes see. It is Balanchine’s genius to match musical effects

with synonymous statements from the language of dance, and his vocabu-

lary is as rich in nuance and inflection as any story.

Performances varied. The Duo Concertant received superb performances

by Miss Mazzo and Martins, who continue to grow in both individual excel-

lence and mutual affinity, and Barocco was likewise outstanding. The eight girls of the corps, in particular, performed with a polished maturity that

enhanced the work’s strength.

But a Symphony in C that I also saw seemed underrehearsed. When the

entire company filled the stage for the final pages of the last movement, a

passage performed in unison and whipped up to a fine frenzy, the corps

looked like a spastic centipede.

Such things, however, will happen. As the season progresses, the blem-

ishes will disappear. In any event, they hardly mar a company that is as

blessed in repertory and performers as the City Ballet is today.

May 12, 1974

52

Setting New Standards

W

Lovely Dream of Balanchine

Few full-length dances are as literarily rich as George Balanchine’s version

of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which the New York City Ballet performed

last night in the Kennedy Center Opera House, and few are as lovely to

look at.

Though the piece is an anomaly in Balanchine’s career, which has been

built mainly on plotless ballets, it nonetheless sits squarely in the tradition

of narrative dance theater. Indeed, its theme is another thread that ties Bal-

anchine to the past. As he does in a handful of other works, Don Quixote,

for instance, or Harlequinade, Balanchine here is following a precedent set in Imperial Russia by Marius Petipa, the ballet master he most resembles in his

fertile productivity and who choreographed a Dream a century ago.

Balanchine’s Dream is a marvel of poe