part three

a c L A S SICA L K A LEIDOSCOPE

:

The truest expression of a people is in its dance

and in its music. Bodies never lie.

— agn e s de m i l l e

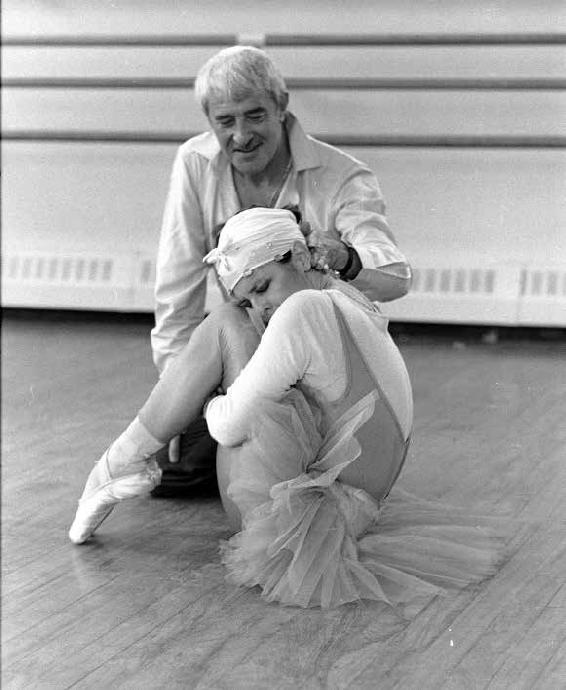

above Kenneth McMillan and Lynn Seymour in rehearsal.

Photo: Anthony Crickmay. © Anthony Crickmay / Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

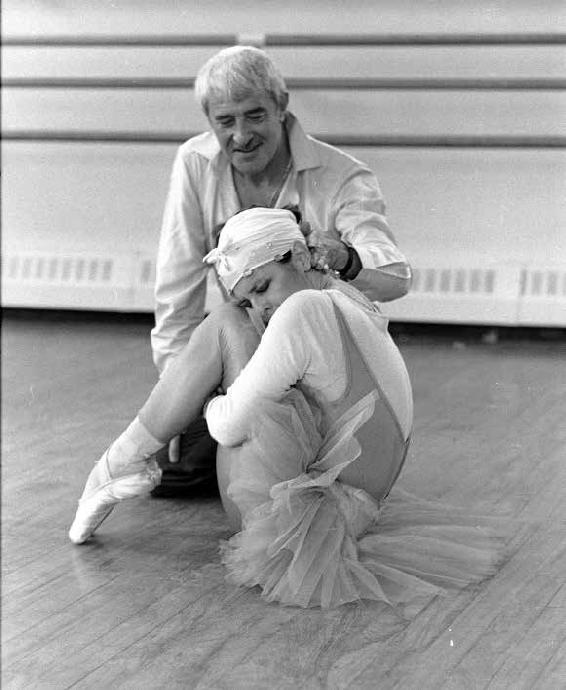

previous Lynn Seymour and Anthony Dowell with Frederick Ashton

rehearsing A Month in the Country, London, 1976. Photo: Anthony Crickmay.

© Anthony Crickmay / Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

w Roya l Ba l l e t w

A New Royal Ballet Takes Shape Under MacMillan

london — A year has passed since Frederick Ashton ended his tenure

with the Royal Ballet. As its director, he was architect of the company’s

international fame, not only contributing dances of his own composition

to the repertory, but also enriching it with works by virtually every other

major choreographer, and not only building a corps of the highest order, but

also engaging the finest solo dancers of his day. Impeccably tasteful, inven-

tive, and intelligent, the personality of the Royal was Ashton’s own.

As inheritor of this legacy, Kenneth MacMillan was in no enviable posi-

tion, though perhaps nobody was better qualified to care for the company.

MacMillan was on intimate terms with the Royal, having cut his cho-

reographic teeth as a member of the troupe in the 1950s. Since then, his ar-

tistic as well as administrative abilities matured impressively. Before being

called to the Royal, he was building Germany’s finest ballet at the Deutsche

Oper in West Berlin, and the magnitude of this feat—made nearly impos-

sible by official provincialism and popular ignorance—prepared him hand-

somely for his present position.

MacMillan has wasted no time in re-forming the Royal. Although it

will be years before the troupe assumes his image, changes of structure and

substance already have taken place. A new Royal Ballet is being born.

The most fundamental of MacMillan’s changes has been merging the

former Touring Company and its parent organization. From this expanded

troupe, in residence at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, a splinter

group has been formed. It, too, is called the Touring Company, but unlike

93

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

its earlier namesake, it is the equal of the larger company in technical ex-

pertise, sharing many of the same dancers, and perhaps even more interest-

ing in repertory.

The small Royal, based at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, serves a double

function by performing classics from the formative years of British ballet—

the 1930s—that MacMillan has so wisely revived and by giving today’s

younger choreographers a place to experiment, a hothouse in which their

ideas can grow.

On a recent visit, which proved typical of its activity, one of the works I

saw, one that I was delighted to finally catch up with, was The Rake’s Progress, choreographed in 1935 by Ninette de Valois. Based on the well-known set of

Hogarth etchings, The Rake is a cornerstone of the highly theatrical genre of dance that the English have made their own, yet ironically it stands outside

the mainstream of modern British ballet. Robert Helpmann, John Cranko,

Jack Carter, Frank Staff—many of their works would be unthinkable were

it not for the pioneering efforts of de Valois, for her imaginative extension

of ballet’s dramatic scope.

It’s unfair to judge The Rake as choreography, really, for just as its in-

spiration comes from the visual arts, its plastic impulse is from the world

of mime. De Valois’ characters are identified by a wealth of explanatory

gestures and poses; dance is secondary. She fleshes them out until they are

three-dimensional caricatures, and she infuses them with a moralistic spirit

close to Hogarth’s own. Considered as choreography, Rake’s Progress is a

primitive. But like the best of its genre, it has an unselfconscious sophistica-

tion, an elemental force, and an honest insight that set it apart.

Ashton is represented in the repertory by Les Patineurs, which shows

him at his happiest. Premiered in 1937, the piece is no more than a diver-

tissement whose dances are thematically wedded one to another by its ice-

skating motif.

In his choreography, Ashton capitalizes on this flimsy subject matter in a

variety of ways: by humorous contretemps, such as a dancer slipping to the

ice, and more integrally, by technical tricks suggestive of skating—walking

cautiously en pointe, gliding in rhythmic glissés, and spinning in whirlwind pirouettes.

The piece is first cousin to Les Rendezvous, which was, in fact, first seen at the Wells in the year of Patineurs’ premiere (although Ashton had created it four years earlier for the Camargo Society). Relating the two are their

94

A Classical Kaleidoscope

nineteenth-century French scores orchestrated by Constant Lambert; their

stylish sets and costumes by William Chappell; their fine sense of line, eco-

nomical choreography, and subtle construction; and their blithe spirit and

good humor. Ashton was magical in these works in a way all his own.

Another favorite that is back in the repertory is John Cranko’s homage

to Gilbert and Sullivan, Pineapple Poll. Now that his passion is full-length ballets of the most tragic and often turgid sort, I would almost expect Cranko

to disown this carefree romp, whose only reason for being is the pleasure it

affords. In the 20 seasons since its premiere, it hasn’t aged at all. And even

if it’s a bit too long, a bit too windy, and a bit too silly, it’s still perhaps the funniest, sunniest work in the Royal’s repertory.

Although I saw none of the newest pieces, it was good to remake the

acquaintance of Kenneth MacMillan’s 1963 Las Hermanas. As in The Burrow, MacMillan has here used a score by the Swiss composer Frank Martin and

a striking set by Nicholas Georgiadis. Both are first-rate. So is the dance, a

near-perfect retelling of Lorca’s tragedy, The House of Bernarda Alba. Only its ending flaws the work, when the Youngest Sister is found to have hung herself. For such a powerful stroke we haven’t been emotionally prepared, and

it all seems too swift. But Hermanas is an honest and telling work, worthy of Lorca in its sensitivity and dramatic integrity. And it lets Lynn Seymour

give a searing performance as the Eldest Sister.

While smaller works such as these are being played at the Wells, large-

scale, lavish ballets can be seen at the Royal Opera House.

Giselle is possibly the best of these larger productions. Although nobody

will admit it, the version danced by the Royal is closely modeled on the

staging done by Leonid Lavrovsky for the Bolshoi Ballet. Structural simi-

larities suggest the affinity—the substitution of a pas de six for the act I

“Peasant” pas de deux, for instance, or the way in which the work closes,

with the curtain falling as a grief-stricken Albrecht walks towards the au-

dience. And the relation is made plain by the heightened theatricality that

makes the piece so vibrantly alive.

A generation of Soviet choreographers, of which Lavrovsky is foremost,

was strongly influenced by the great theater director Constantin Stanislav-

sky. To these artists, dramatic fidelity became as important as dance itself.

In practical terms, Stanislavsky’s theories were made manifest in the

quality of the acting. In opposition to the mime one most often sees, clumsy

movements that are a sign language for predigested phrases, the acting of

95

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

the Russians and of the English in this Giselle looks completely natural and lifelike. Which is because the dancers are taught to talk silently, to speak

speechless words and color them with bodily inflection. The effect of this is

most closely compared with a silent film, in which conversations are easily

understandable and naturally expressed. Taken for granted on the screen,

the effect is revelatory on the stage.

Desmond Kelly, who made Washington so much poorer when he joined

the Royal, was a wonderfully moving and complete Albrecht. His acting

was superb throughout (if too close to breast-beating at the end of act I)

and alive with little details (such as his discreet flirting with Giselle during

the pas de six). Technically, he looked marvelous. If he doesn’t have the

sex appeal of Nureyev in this role, and never will, he makes up for it with

a characterization that is a model of aristocracy, intelligence, and charm.

Doreen Wells, seen in the title role, is an excellent actress, but her dancing

is uneven. It’s fine from the waist down, but somewhat stiff in the arms and

upper carriage. She’s so attractive, though, that you often don’t notice.

Swan Lake with Margot Fonteyn and Nureyev was as indifferent as Giselle was exhilarating. The production itself is a hash, Petipa/Ivanov/Sergeyev to

start with, plus some music-hall numbers added by Ashton, plus a dreadful

“Peasant Dance” by de Valois.

Although the leading roles were filled with much of the brains and virtu-

osity we’ve come to expect, at the performance I saw there was no magic to

the dancing, save for act III, where the Black Swan momentarily sprang to

life. Odile, it seemed, fascinates Dame Margot more than Odette. Nureyev

didn’t exert himself unduly, but got all the accolades he knew he would.

In most everything I attended, the corps de ballet was far sloppier than

it should have been. If the repertory has been invigorated since MacMillan’s

arrival, the company’s level of execution has slipped noticeably. Dancing

in so broad a spectrum of works seems to have thinned the quality of the

company as a whole. And so a retrenchment is in order, a trimming of a

too-sudden and luxuriant growth. Without exemplary dancing, there’s no

justification for even the most marvelous of repertories.

June 20, 1971

96

A Classical Kaleidoscope

W

Royal Ballet Gives Incomparable Giselle

new york — The Royal Ballet’s Giselle holds a special interest for Wash-

ingtonians, for it’s a production in which Desmond Kelly, the Royal’s most

recent acquisition and a stalwart of the National Ballet, undoubtedly will

dance. Kelly is currently in London with the Royal’s smaller troupe, while

the main company is here playing the Metropolitan Opera. On Sunday,

with Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, the company gave an incompa-

rable Giselle.

Fonteyn first. What made her work so special was not her technical fi-

nesse—although it’s a marvel how refined and beautiful her dancing still is,

even if she takes the liberty of simplifying certain passages—but the special

understanding she has of the heroine.

In character, Giselle is not the prima donna who most often portrays

her, but rather a child, the youngest of her circle, the most fragile both in

physique and psyche. She’s the idealized 16-year-old, just emerging from

the shadow of her overprotective mother and too much in love with the joy

of dancing and with love itself, which will lead her to tragedy.

Though she first danced Giselle in 1937, Fonteyn still is uncannily con-

vincing as this distracted teen: sweet, reckless, and innocent. Her first act,

especially, from her initial meeting with the Count, as he surprises her from

behind, to the mad scene and her death in his arms, was effective in every

detail and utterly touching.

I don’t know how Nureyev spent the time between Friday night—when

midperformance he walked off the stage in a moment of pique after acciden-

tally kicking a colleague—and Sunday night, but he was at his brilliant best

as Albrecht, and as such in a class by himself.

He’s literally a stunning dancer—at one point the audience gasped in

unison at a perfectly executed grand jeté en tournant—and his concentrated power comes in large part from dramatic precision and economy. Follow

him closely. If the simplest step or gesture is repeated twice, say, it’s pre-

cisely the same each time. For Nureyev has honed his every movement down

to its truest and most telling state and has polished it with his personality

and theatrical élan. Nothing he does is extraneous or irrelevant, and to my

eyes this perfection is the crucial part of his great beauty.

97

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

As for the rest of the cast, Wayne Sleep impressed the audience in the

“Peasant” pas de deux with his tremendous energy and fierce determina-

tion, but this couldn’t compensate for his sloppy changements and haphazard poses. Lesley Collier, whom he partnered, was fine when the line was sharp

and detailed and less impressive in legato work.

Deanne Bergsma was a detached and elegant Myrtha, and Gerd Larsen

and Leslie Edwards both lucid in their mimed roles of Berthe and Hilarion.

The girls in the corps looked marvelous—and despite its expensive so-

loists, Giselle is very much the corps’ ballet. I wish Ashton hadn’t relocated Giselle’s tomb stage rear, for the mystery of her entrances and exits has

been staged out of existence. But this is the smallest of reservations to what

otherwise was a lovely and memorable show.

May 19, 1970

W

Royal Ballet’s Anastasia

new york — Once the standard of international dance, the Royal Ballet

no longer reigns supreme. Since Kenneth MacMillan succeeded Frederick

Ashton in the role of artistic director, the company has lost considerable

ground. Crucial and damaging change has come to the repertory, which for

decades reflected the literate sophistication and choreographic charm that

so personally were Sir Frederick’s own.

MacMillan, of course, is different, but also less distinguished. In artistic

temperament and talents, he’s far closer to John Cranko, his contemporary

and director of the Stuttgart Ballet, than he is to Ashton.

His specialty is the full-length story ballet that relies as much on its

decor as it does on its dance. It’s spectacle, really, and its aesthetic bent is

indebted in part to the super-theatrical productions of the Bolshoi, and in

lesser measure to the works of Ninette de Valois.

The Rake’s Progress, for instance, which the Royal premiered in 1935, is

essentially an extra-choreographic piece of theater. De Valois’ subject is not

the dance itself, not movement as metaphor, but rather the literary content

of a set of etchings. As a model of efficiency and force, Rake is a work that MacMillan must greatly admire, and it is not at all surprising that he rein-troduced it into the repertory as soon as he took command.

98

A Classical Kaleidoscope

Anastasia, whose dedicatee is de Valois, is MacMillan’s latest large-scale production, and much of it is preposterous, from the heroine’s first entrance

on roller skates to her ultimate exit on a magically ambulatory bed. But

there’s much, too, that is effective and touching and makes one wish that

MacMillan would take the time and effort to rethink the piece.

The ballet is a dramatization of the childhood, adolescent traumas, and

eventual hospitalization of Anna Anderson, who claims to be the succes-

sor to the Romanov throne by virtue of being the daughter of Nicholas

and Alexandra, the Tsar and Tsarina who were murdered during the 1918

Revolution. Assisting these principals are Rasputin, the peasant monk who

purportedly had power to cure the Tsarevitch of his hemophilia; Kschessin-

ska, the prima ballerina assoluta of the Mariinsky Ballet, who was the

Tsar’s mistress before his accession; and the traditional supporting cast of

thousands.

Oddly, for personalities that were so strong while alive, MacMillan has

devised singularly insipid choreography. The success of Anastasia comes not from any striking portrayals, but rather from a genuine feeling for the leisurely atmosphere of waning aristocracy, from a very few dances of special

distinction that are scattered throughout the piece, and from several scenes

that are in perfect dramatic proportion to the overall story. I’m thinking of

one such as that in act II where an unseen Anastasia watches while the peo-

ple who rule her life dance a quiet and somehow sinister quartet. Though

the incident has no historical validity, it’s convincing in the context of the

ballet’s freer reading.

The high quality of such moments makes one especially regretful that so

much of the work is banal. Primarily a pas de deux choreographer, MacMil-

lan can’t think of anything interesting for larger ensembles. The ballroom

dances do no more than mimic the music, while the dances for the naval

officers look like a cross between Moiseyev’s Partisans and Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes.

And then there’s the third act, the least persuasive of all. Set to music

by Bohuslav Martinu˚, it takes us inside Anastasia’s by-now-demented mind

as she reviews the various tragedies of her life. The atmosphere is stark

and clinical; the theatrics, advanced. Electronic music prefaces the Martinu˚

score, and visual projections of Anna’s past are shown.

Yet so strong a juxtaposition proves impossible. Theatrically, it demands

too much. For two acts the drama is linear and our point of view outside the

99

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

action. Now MacMillan shifts from his objective and narrative position and

scrambles in time the events in Anna’s mind. Musically, the stylistic switch

from Tchaikovsky—whose music was heard in acts I and II—to Martinu˚ is

jarring and destructive of the overall ambience. Visually, the atmospheric

decor by Barry Kay is replaced in this act with an ineffective sparseness.

The performances I saw were, in large part, fine, though dancers aren’t

asked to reveal much by such timid choreography. Lesley Collier was An-

astasia, Georgina Parkinson and Michael Somes the Tsarina and Tsar, and

Diana Vere danced Kschessinska.

Could a new score be found for the final act, perhaps one of Tchai-

kovsky’s darker tone poems such as The Tempest or Voyevode, and could the other acts be tightened, Anastasia might have the historical and choreographic conviction that at present are only promised.

June 7, 1972

W

MacMillan’s Romeo a Flawed Success at Best

Kenneth MacMillan’s production of Romeo and Juliet, which the Royal Ballet performed in the Kennedy Center Opera House, can’t be faulted at all for

its dancing. The piece itself is something else again.

To start at the periphery, both shows I saw were given added interest

through the appearances is mime roles of Gerd Larsen and Michael Somes.

She is the company’s senior teacher; he is principal répétiteur and one of the

great dancers emeritus of British ballet. As the Nurse and Lord Capulet,

they added a maturity of expression and confirmed a continuity of tradition

that in the realm of mime is matched only by the Danes.

Antoinette Sibley and Anthony Dowell were gorgeous in the title roles.

In a work so frankly dramatic, Dowell is a great beauty—impetuous, Byro-

nic, aloof. His dancing was technically splendid and far more comfortable

than in an earlier Bayadère, and his acting, as well, was wonderfully apt.

He gives a thoroughly considered performance. Among its many telling

details were the simultaneous resolve and reluctance to face Tybalt when he

first was found with Juliet, the tentative glances he shyly shot her at the start

of their initial pas de deux, and the air of distracted isolation in the market

on the morning after the ball.

100

A Classical Kaleidoscope

Miss Sibley’s acting, too, was rich in the apposite gesture. Examples:

her strikingly confused excitement when she touches her breasts and sud-

denly becomes aware that a woman is growing from a girl, and her artfully

feigned headache when she would elude the intrusive Paris.

Merle Park and Rudolf Nureyev provided a splendid contrast in the

weekend’s second performance. Nureyev plays a youthful Romeo. Rosalind

accents his unripe age when she dismisses him at the outset, and his reckless

bravado is reconfirmed when he is quick to draw his sword against Tybalt.

Early scenes started slowly, but when Nureyev found his stride, his dancing

was at its unparalleled prime.

Miss Park is like Fonteyn in her dancing’s fluid purity. As an actress her

gestures can be rather too broad, but temperamentally she has an innocence

that recalls no one as much as Dame Margot.

Monica Mason, in both performances, was a wickedly vivacious Harlot,

and Wayne Sleep led the “Mandolin Dance” with virtuosic flair. As Mercu-

tio and Benvolio, Michael Coleman and David Ashmole were excellent, and

as Tybalt, Desmond Doyle was an imposing presence.

The work, though, is a big disappointment. It would take an artist of

outsized stature to make dances as strong as Prokofiev’s score. It is mar-

velously vibrant music and so explicit in its vividly painted incident that it

leaves the choreographer little independent imaginative freedom.

Though the story is told with pervasive grace, at critical moments Mac-

Millan fails. When Juliet, for instance, resolves to visit Friar Laurence, a

thematic turning point of major importance, she sits on her bed like a stone;

when Romeo receives the letter of instruction from the Nurse, he inanely

spins in circles, too obviously showing glee.

The language of the dance has lost its vitality. Antony Tudor, in his set-

ting of the story, tells us worlds about Juliet through a simple rise to demi-

pointe as she makes her entrance, surely among the most poetic gestures in the annals of dance. MacMillan, in the same scene, is inarticulate. His steps

might be technically persuasive, but they register only as tricks; they are

effects divorced from causes.

The finest ballet sets are currently made by Nicholas Georgiadis—note

his atmospheric work for MacMillan’s Anastasia and his opulent decor for

Nureyev’s Sleeping Beauty—and his Romeo is resplendent. Rich with mock-marble walls and architectural details that fix time and place, it is more

Italianate than the Elizabethan Romeo designed by Juergen Rose for John

101

A Beautiful Time for Dancers

Cranko’s Stuttgart production and as appealing as the extraordinarily

beautiful quattrocento sets drawn by Eugene Berman for Ballet Theatre’s

production of Tudor’s Romeo.

The dances, though, must take primacy, and for all their incidental plea-

sures, MacMillan’s Romeo is at best a flawed success.

June 3, 1974

W

“The More You Dance, the Better It Gets, No?”

He is more than the star performer who shot to the apex of Western dance

when he left his Russian homeland in 1961; he is more than the darling of

socialites who queue up to bask in his glory; and he is infinitely more than

the idol of the insidious cult of ballet freaks.

Rudolf Nureyev may play all these roles, but he has, as well, a private

<