Part 1

Buddhadasa's Youth

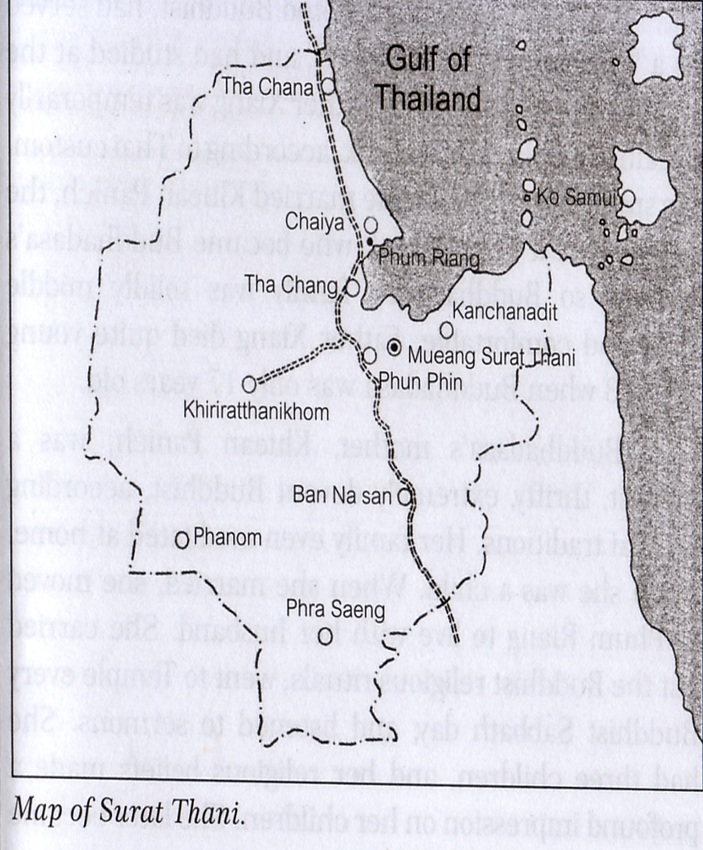

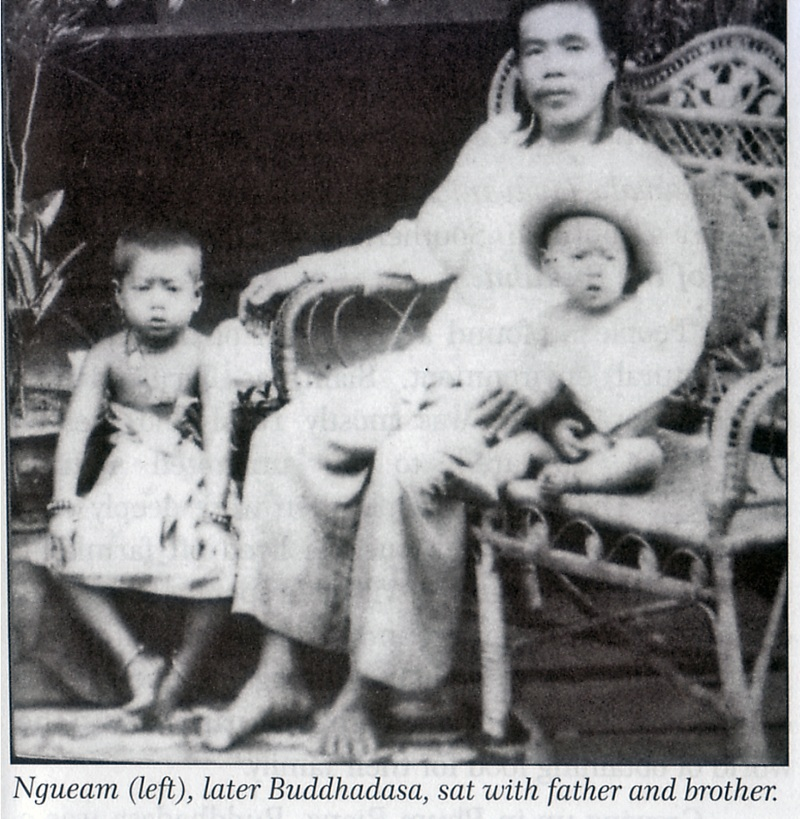

Ajahn Buddhadasa was born in southern Thailand in 1906, and given the name Ngueam Panich. He was the eldest of three children of Xiang Panich, a middle class merchant of Chinese ancestry, and a Thai mother named Kluean. His family ran a small grocery store in Phum Riang, near the ancient Kingdom of Chaiya, in southern Thailand.

Father Xiang Panich, was a merchant from an ethnic Chinese family who had immigrated to Phum Riang so long ago that they were fully assimilated into the local culture. His father was a kind man, industrious and gentle. He loved to write poetry. He neither drank alcohol nor smoked, nor gambled. He practiced the Buddhist non-violent precepts.

The Phanich family was reasonably well off, and their family store functioned as the local meeting place and as the police station before the district center was moved to Chaiya, just before the Second World War.

Chinese immigrants had arrived in Thailand in great numbers during the 19th century, when King Mongkut abolished slavery and began hiring low-wage Chinese immigrants to do the public works. They were mostly men, and often married Thai women. These families became the business class in Thailand, and embraced the modern reforms of King Mongkut. With their business skills, they became the backbone of the new modern, urbanized middle class, mostly centered in Bangkok, and were in close cooperation with western enterprise in Thailand. As a shopkeeper's son, Buddhadasa was born into this new emerging middle class.

Father Xiang was a devoted Buddhist, had served as a "temple-boy" in his youth, and had studied at the temple school. As a youth, father Xiang was temporarily ordained as a Buddhist monk, according to Thai custom. He spoke little Chinese. He married Kluean Panich, the daughter of a Thai official, who became Buddhadasa's mother, so Buddhadasa's family was solidly middle class and comfortable. Father Xiang died quite young in 1923 when Buddhadasa was only 17 years old.

Buddhadasa's mother, Kluean Panich, was a modest, thrifty extremely devout Buddhist, according to Thai traditions. Her family even meditated at home, when she was a child. When she married, she moved to Phum Riang to live with her husband. She carried out the Buddhist religious rituals, went to Temple every Buddhist Sabbath day, and listened to sermons. She had three children, and her religious beliefs made a profound impression on her children. She later became a strong patron of Buddhadasa's work.

Phum Riang, at that time was a small town. People of Phum Riang were fishermen and rice farmers. Fishing was small scale. The people led simple lives.

Thai society was very hierarchical, and the people felt they lived on different levels. Officials had much higher status that regular village farmers and fishermen. But the different strata of society cooperated with one another for the common good. The people were earnest in merit making. Buddhism played a profound role in the daily lives of the people, both high and low.

The local monastery was the center of the community. Every house had a table set up with alms ready to be offered to monks every morning. Once a week, people would go to a nearby temple and listen to sermons and prayers. Life was peaceful and rather care free. There was no need to shut the doors or windows. The villagers didn't have to worry about burglars. They knew each other well, like relatives.

Kamala Tiyavanich described the world of Buddhadasa's youth in Southern Thailand in her book Sons of the Buddha . "People ... found a great deal of their food in the natural environment. Siam, as Thailand was called before 1939, was mostly rural and blessed with what appeared to be unlimited natural resources. The lives of people then were deeply connected with nature; most people lived off farmland, forests, rivers, and the sea. Villagers spent a lot of time outdoors; people went around barefoot; boys and girls knew how to cook, clean house, tend gardens, take care of livestock, haul water, and help their parents with the world of obtaining food for their family."

Growing up in Phum Riang, Buddhadasa was a regular mischievous child. He was often spanked by his mother for getting into squabbles or playing pranks on his two siblings. And he was afraid of ghosts. Buddhadasa told a story on himself. One day, the cattle he was tending ventured out into a graveyard. It was dusk already. He was very scared but then a thought came to him: "I am afraid of ghosts, but look, those cattle just stalked there to nibble grass." The fear melted away and Buddhadasa said he was grateful to the cattle for teaching him a valuable lesson."

Buddhadasa's mother was a strict disciplinarian, and very thrifty and industrious, and transmitted these values to her children. He learned the art of Thai cooking from his mother. "My father wasn't at home much. Mother was there all the time. I was much closer to mother, and because I had to help her in the kitchen, I learned to do everything in the kitchen just the way mother did. Father was a good cook, too, better than most women. His mother sold many kinds of sweets and was really talented."

"Preparing good food is an art. My father could cook like a woman because his mother made him. He was forced to learn by circumstances. I could cook because mother had me helping her in the kitchen when I was still quite young."

Whatever we did, mother would remind us to do our best. We were warned regularly not to do things crudely." Buddhadasa remembered.

Buddhadasa learned frugality from his mother. "If you want (to know) what I received from my mother, that would be frugality; care and thriftiness in spending. We were taught to be thrifty. Even with water for washing our feet, we were forbidden to use a lot. If we wanted a drink of water, we weren't allowed to take just one sip from the dipper and throw the rest away. We had to use the appropriate amount of firewood. If any was incompletely burned, we had to quench the fire and save unburned wood for later use. Everything that could be conserved had to be conserved, and there was a lot. We were frugal in every way, so it became a habit. I consider this all the time; useful ways to save and how to do it."

"Mother conserved very carefully. She saved time, too; time had to be used beneficially. When resting she didn't waste time doing nothing. She had to have something useful to do."

In 1912, when Buddhadasa was six

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12