CHAPTER VI

I DECLINE MATRIMONY AND WED ART

The great change began in me from that day. For rather a long time, indeed, my soul remained childlike, but my mind discerned life more distinctly. I felt the need of creating a personality for myself. That was the first awakening of my will. I wanted to be some one. Mlle. De Brabender declared to me that this was pride. It seemed to me that it was not quite that, but I could not then define what the sentiment was which imposed this wish on me. I did not understand until a few months later why I wished to be some one.

A friend of my godfather’s made me an offer of marriage. This man was a rich tanner, and very kind, but so dark and with such long hair and such a beard that he disgusted me. I refused him, and my godfather then asked to speak to me alone. He made me sit down in my mother’s boudoir, and said to me:

“My poor child, it is pure folly to refuse M. B——. He has sixty thousand francs a year and expectations.”

It was the first time I had heard this use of the word, and when the meaning was explained to me I wondered if that was the right thing to say on such an occasion.

“Why, yes,” replied my godfather, “you are idiotic with your romantic ideas. Marriage is a business affair, and must be considered as such. Your future father and mother-in-law will have to die, just as we shall, and it is by no means disagreeable to know that they will leave two million francs to their son, and consequently to you, if you marry him.”

“I shall not marry him, though.”

“Why?”

“Because I do not love him.”

“But you never love your husband before—” replied my practical adviser. “You can love him after.”

“After what?”

“Ask your mother. But listen to me now, for it is not a question of that. You must marry. Your mother has a small income which your father left her, but this income comes from the profits of the manufactory which belongs to your grandmother, and she cannot bear your mother, who will therefore lose that income, and then have nothing and three children on her hands. It is that accursed lawyer who is arranging all this. The whys and wherefores would take too long to explain. Your father managed his business affairs very badly. You must marry, therefore, if not for your own sake, for the sake of your mother and sisters. You can then give your mother the hundred thousand francs your father left you, which no one else can touch. M. B—— will allow you three hundred thousand francs. I have arranged everything, so that you can give this to your mother if you like, and with four hundred thousand francs she will be able to live very well.”

I cried and sobbed, and asked to have time to think it over. I found my mother in the dining-room.

“Has your godfather told you?” she asked gently, in rather a timid way.

“Yes, mother; yes, he has told me. Let me think it over, will you?” I said, sobbing, as I kissed her neck lingeringly.

I then locked myself in my bedroom, and, for the first time for many days, I regretted the separation from my convent. All my childhood rose up before me, and I cried more and more, and felt so unhappy that I wished I could die. Gradually, however, I began to get calm again and realized what had happened, and what my godfather’s words meant. Most decidedly I did not want to marry this man. Since I had been at the Conservatoire, I had learned a few things vaguely, very vaguely, for I was never alone, but I understood enough to make me not want to marry without being in love. I was, however, destined to be attacked in a quarter from which I should not have expected it. Mme. Guérard asked me to go up to her room to see the embroidery she was doing on a frame for my mother’s birthday.

My astonishment was great to find M. B—— there. He begged me to change my mind. He made me very wretched, for he pleaded with tears in his eyes.

“Do you want a larger marriage settlement?” he asked. “I would make it five hundred thousand francs.”

But it was not that at all, and I said in a very low voice:

“I do not love you, monsieur.”

“If you do not marry me, mademoiselle,” he said, “I shall die of grief.”

I looked at him and repeated to myself the words, “die of grief.” I was embarrassed and desperate, but at the same time delighted, for he loved me just as a man does in a play. Phrases that I had read or heard came to my mind vaguely, and I repeated them without any real conviction, and then left him without the slightest coquetry.

M. B—— did not die. He is still living, and has a very important financial position. He is much nicer now than when he was so black, for at present he is quite white.

I had just passed my first examination with remarkable success, particularly in tragedy. M. Provost, my professor, had not wanted me to compete in “Zaïre,” but I had insisted. I thought that scene with Zaïre and her brother Nivestan very fine, and it suited me. But when Zaïre, overwhelmed with her brother’s reproaches, falls on her knees at his feet, Provost wanted me to say the words, “Strike, I tell you! I love him!” with violence, and I wanted to say them gently, perfectly resigned to a death that was almost certain. I argued about it for a long time with my professor, and finally I appeared to give in to him during the lesson. But on the day of the competition I fell on my knees before Nerestan with a sob so real, my arms outstretched, offering my heart so full of love to the deadly blow that I expected, and I murmured with such tenderness, “Strike, I tell you! I love him!” that the whole house burst into applause and demanded it twice over.

The second prize for tragedy was awarded me, to the great dissatisfaction of the public, as it was thought that I ought to have had the first prize. And yet it was only just that I should have the second, on account of my age and the short time I had been studying. I had a first accessit for comedy in “La Fausse Agnes,” and Sarcey wrote an article about it.

I felt, therefore, that I had the right to refuse M. B——. My future lay open before me, and consequently my mother would not be in want if she should lose her present income. A few days later, M. Régnier, professor at the Conservatoire and secretary of the Comédie Française, came to ask my mother whether she would allow me to play in a piece of his at the Vaudeville. The piece was “Germaine,” and the managers would give me twenty-five francs for each performance. I was amazed at the sum! Seven hundred and fifty francs a month for my first appearance! I was wild with joy. I besought my mother to accept the offer made by the Vaudeville, and she told me to do as I liked in the matter.

I asked M. Camille Doucet, director of the Beaux-Arts, to allow me to recite something to him, and, as my mother always refused to accompany me, Mme. Guérard went with me. My little sister, Régina, begged me to take her, and very unwisely I consented. We had not been in the director’s office more than five minutes before my sister, who was only six years old, began to climb on the furniture. She jumped on a stool, and finally sat down on the floor, pulling the paper basket, which was under the desk, toward her, and proceeded to spread all the torn papers which it contained about the room. On seeing this, Camille Doucet mildly observed that she was not a very good little girl. My sister, with her head in the basket, answered in her husky voice:

“If you bother me, monsieur, I shall tell everyone that you are there to give out holy water that is poison—my aunt says so.”

My face turned purple with shame, and I stammered out:

“Please do not believe that, M. Doucet, my little sister is telling an untruth.”

Régina sprang to her feet and, clenching her fists, rushed at me like a little fury:

“Aunt Rosine never said that?” she exclaimed. “You are telling the untruth ... why, she said it to M. De Morny, and he answered....”

I had forgotten this, and I have forgotten what the Duc de Morny answered, but, beside myself with anger, I put my hand over my sister’s mouth and took her quickly away. She howled like a wildcat, and we rushed like a hurricane through the waiting room which was full of people. I then gave way to one of those violent fits of temper to which I had been subject in my childhood. I sprang into the first cab that passed the door, and, when once in the cab, struck my sister with such fury that Mme. Guérard was alarmed, and protected her with her own body, receiving all the blows I gave with my head, arms, and feet, for in my anger, rage, and shame I flung myself about to right and left. My rage was all the more profound from the fact that I was very fond of Camille Doucet. He was gentle and charming, affable and kind-hearted. He had refused my aunt something she had asked for, and, unaccustomed to being refused anything, she had a spite against him. This had nothing to do with me, though, and I wondered what Camille Doucet would think. And then, too, I had not asked him about the Vaudeville.

All my fine dreams had come to nothing. And it was this little monster, who looked as fair and as white as a seraph, who had just shattered my hopes. Huddled up in the cab, an expression of fear on her self-willed face, and her thin lips compressed, she was gazing at me under her long lashes with half-closed eyes. On reaching home I told my mother all that had happened, and she declared that my little sister should have no dessert for two days. Régina was greedy, but her pride was greater than her greediness. She turned round on her little heels and, dancing her jig, began to sing, “My little stomach isn’ at all glad,” until I wanted to rush at her and shake her.

A few days later, during my lessons, I was told that the Ministry refused to allow me to act at the Vaudeville.

M. Régnier told me how sorry he was, but he added in kindly tone:

“Oh, but, my dear child, the Conservatoire thinks a lot of you! Therefore you need not worry too much.”

“I am sure that Camille Doucet is at the bottom of it,” I said.

“No, he certainly is not,” answered M. Régnier, “Camille Doucet was our warmest advocate, but the Ministry will not, upon any account, hear of anything that might be detrimental to your début next year.”

I at once felt most grateful to Camille Doucet for his kindness in bearing no ill-will after my little sister’s stupid behavior. I began to work again with the greatest zeal, and did not miss a single lesson. Every morning I went to the Conservatoire with my governess. We started early, as I preferred walking to taking the omnibus, and I kept the franc which my mother gave me every morning, part of which was for the omnibus and part for cakes. We were to walk home always, but every other day we took a cab with the two francs I had saved for this purpose. My mother never knew about this little scheme, but it was not without remorse that my kind Brabender consented to be my accomplice.

As I said before, I did not miss a lesson, and I even went to the deportment class, at which poor old M. Elie, duly curled, powdered, and adorned with lace frills, presided. This was the most amusing lesson imaginable. Very few of us attended this class, and M. Elie avenged himself on us for the abstention of the others. At every lesson each one of us was called forward. He addressed us by the familiar term of thou, and considered us as his property. There were only five or six of us, but we each had to mount the stage. He always stood up with his little black stick in his hand. No one knew why he should have this stick.

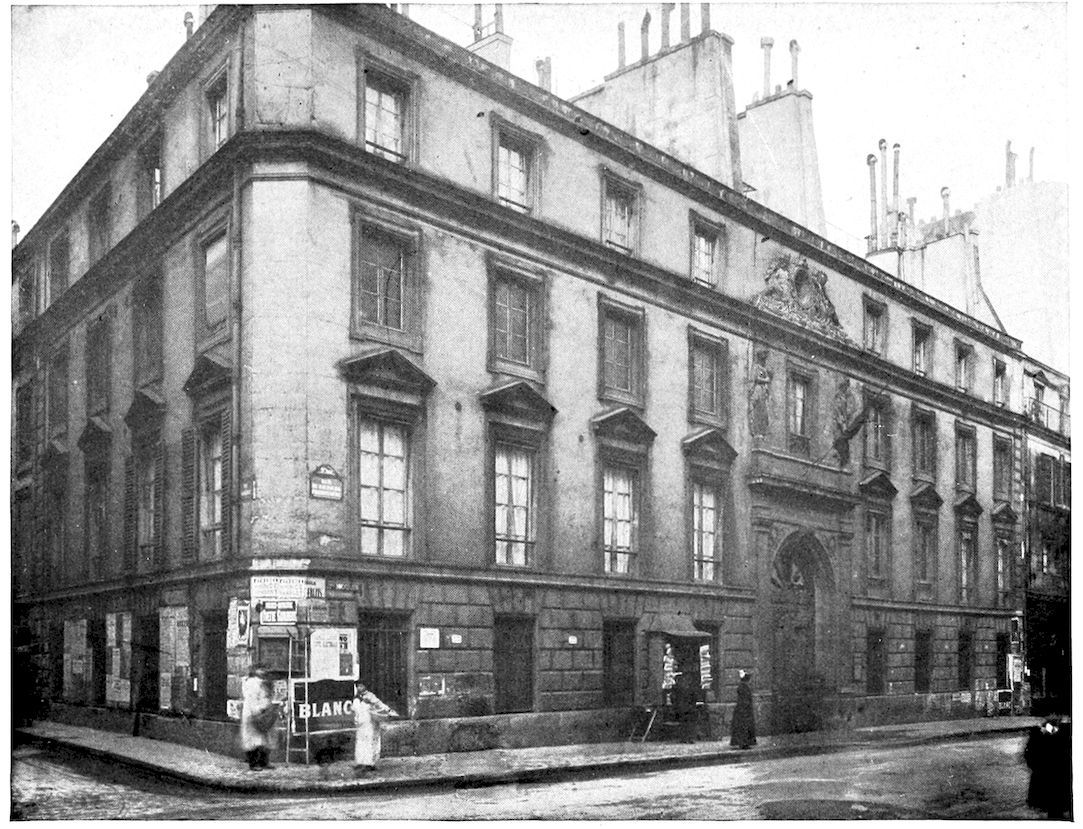

LE CONSERVATOIRE NATIONAL DE MUSIQUE ET DE DECLAMATION, PARIS.

“Now, young ladies,” he would say, “the body thrown back, the head up, on tiptoes—that’s it—perfect. One, two, three, march.”

And we marched along on tiptoes with heads up and eyelids drawn over our eyes as we tried to look down in order to see where we were walking. We marched along like this with all the stateliness and solemnity of camels! He then taught us to make our exit with indifference, dignity, or fury, and it was amusing to see us going toward the doors either with a lagging step or in an animated or hurried way, according to the mood in which we were supposed to be. Then we heard: “Enough! Go! Not a word!” for M. Elie would not allow us to murmur a single word. “Everything,” he used to say, “is in the look, the gesture, the attitude!” Then there was what he called “l’assiette,” which meant the way to sit down in a dignified manner, to let oneself fall into a seat wearily, or the “assiette,” which meant: “I am listening, monsieur; say what you wish.” Ah, that was distractingly complicated, that way of sitting down! We had to put everything into it: the desire to know what was going to be said to us, the fear of hearing it, the determination to go away, the will to stay. Oh, the tears that this “assiette” cost me! Poor old M. Elie! I do not bear him any ill-will, but I did my utmost later on to forget everything he had taught me, for nothing could have been more useless than those deportment lessons. Every human being moves about according to his or her proportions. Women who are too tall take long strides, those who stoop walk like the Eastern women; stout women walk like ducks, short-legged ones trot; very small women skip along, and the gawky ones walk like cranes. Nothing can be done for them, and the deportment class has very wisely been abolished. The gesture must depict the thought, and it is harmonious or stupid, according to whether the artiste is intelligent or null. For the theater one needs long arms; it is better to have them too long than too short. An artiste with short arms can never, never make a fine gesture. It was all in vain that poor Elie told us this or that. We were always stupid and awkward, while he was always comic; oh, so comic, poor old man!

I also took fencing lessons. Aunt Rosine put this idea into my mother’s head. I had a lesson once a week from the famous Pons. Oh, what a terrible man he was! Brutal, rude, and always teasing, he was an incomparable fencing master, but he disliked giving lessons to “brats” like us, as he called us. He was not rich, though, and I believe, but am not sure of it, that this class had been organized for him by a distinguished patron of his. He always kept his hat on, and this horrified Mlle. De Brabender. He smoked his cigar, too, all the time, and this made his pupils cough, as they were already out of breath from the fencing exercise. What torture those lessons were! He brought with him sometimes friends of his who delighted in our awkwardness. This gave rise to a scandal, as one day one of these gay spectators made a most violent remark about one of the pupils named Châtelain, and the latter turned round quickly and gave him a blow in the face. A skirmish immediately occurred, and Pons, on endeavoring to intervene, received a blow or two himself. This made a great stir, and from that day forth visitors were not allowed to be present at the lesson. I persuaded my mother to let me discontinue attending this class, and this was a great relief to me.

I very much preferred Régnier’s lessons to any others. He was gentle, had nice manners, and taught us to be natural in what we recited, but I certainly owe all that I know to the variety of instruction which I had, and which I followed up in the most devoted way.

Provost taught a broad style, with diction somewhat pompous but sustained. He especially emphasized freedom of gesture and inflection. Beauvallet, in my opinion, did not teach anything that was good. He had a deep, effective voice, but that he could not give to anyone. It was an admirable instrument, but it did not give him any talent. He was awkward in his gestures, his arms were too short, and his face common. I detested him as a professor.

Samson was just the opposite. His voice was not strong, but piercing. He had a certain acquired distinction, but was very correct. His method was simplicity. Provost emphasized breadth; Samson exactitude, and he was very particular about the finals. He would not allow us to drop the voice at the end of the phrase. Coquelin, who is one of Régnier’s pupils, I believe, has a great deal of Samson’s style, although he has retained the essentials of his first master’s teaching. As for me, I remember my three professors, Régnier, Provost, and Samson, as though I had heard them only yesterday.

The year passed by without any great change in my life, but two months before my second examination I had the misfortune to have to change my professor. Provost was taken ill, and I went in to Samson’s class. He counted very much on me, but he was authoritative and persistent. He gave me two very bad parts in two very bad pieces: Hortense, in “L’Ecole des Vieillards,” by Casimir Delavigne, for comedy, and “La Fille du Cid,” for tragedy. This piece was also by Casimir Delavigne. I did not feel at all in my element in these two rôles, both of which were written in hard, emphatic language.

The examination day arrived, and I did not look at all nice. My mother had insisted on my having my hair done up by her hairdresser, and I had cried and sobbed on seeing this “Figaro” make partings all over my head in order to separate my rebellious mane. Idiot that he was, he had suggested this style to my mother, and my head was in his stupid hands for more than an hour and a half, for he never before had to deal with a mane like mine. He kept mopping his forehead every five minutes, and muttering: “What hair! Good heavens! it is horrible—just like tow! It might be the hair of a white negress!” Turning to my mother, he suggested that my head should be entirely shaved, and the hair then trained as it grew again. “I will think about it,” replied my mother in an absent-minded way. I turned my head so abruptly to look at her when she said this that the curling irons burned my forehead. The man was using the irons to uncurl my hair. He considered that it curled naturally in such a disordered style that he must get the natural curl out of it and then wave it, as this would be more becoming to the face.

“Mademoiselle’s hair is stopped in its growth by this extreme curliness. All the Tangiers girls and negresses have hair like this. As mademoiselle is going on the stage, she would look better if she had hair like madame,” he said, bowing with respectful admiration to my mother, who certainly had the most beautiful hair imaginable. It was fair and so long that, when standing up, she could tread on it and not bend her head. It is only fair to say, though, that my mother was very short.

Finally, I was out of the hands of this wretched man, and was nearly dead with fright after an hour and a half’s brushing, combing, curling, hairpinning, with my head turned from left to right and from right to left. I was completely disfigured at the end of it all, and did not recognize myself. My hair was drawn tightly back from my temples, my ears were very visible and stood out, looking positively improper in their nakedness, while on the top of my head was a parcel of little sausages arranged near each other to imitate the ancient diadem.

I was perfectly hideous. My forehead, of which I caught a glimpse under the golden mass of my hair, seemed to me immense, implacable. I did not recognize my eyes, accustomed as I was to see them veiled by the shadow of my hair. My head seemed to weigh two or three pounds. I was accustomed to do my hair as I still do, with two hairpins, and this man had put five or six packets in it. All this was heavy for my poor head.

I was late, and so I had to dress very quickly. I cried with anger, and my eyes grew smaller, my nose larger, and my veins swelled. But it was the climax when I had to put my hat on. It would not go on the pile of sausages, and my mother wrapped my head up in a lace scarf and hurried me to the door.

On arriving at the Conservatoire, I hurried with my petite dame to the waiting room, while my mother went direct to the hall. When once I was in the waiting room I tore off the lace, and, seated on a bench, after relating the Odyssey of my hairdressing, I gave my head up to my companions. All of them adored and envied my hair, because it was so soft and light and golden. All of them took pity on my sorrow, and were touched by my ugliness. Their mothers, however, were spluttering in their own fat with joy.

The girls began to take out my hairpins, and one of them, Marie Lloyd, whom I liked best, took my head in her hands and kissed it affectionately.

“Oh, your beautiful hair, what have they done to it!” she exclaimed, pulling out the last of the hairpins. This sympathy made me once more burst into tears.

Finally, I stood up triumphant, without any hairpins and without any sausages. But my poor hair was heavy with the beef marrow the wretched man had put on it, and it was full of the partings he had made for the creation of the sausages. It fell now in mournful-looking, greasy flakes around my face. I shook my head for five minutes in mad rage. I then succeeded in making the hair more loose, and I put it up as well as I could with a couple of hairpins.

The competition had commenced, and I was the tenth to be called. I could not remember what I had to say. Mme. Guérard moistened my temples with cold water, and Mlle. De Brabender, who had only just arrived, did not recognize me, and was looking about for me everywhere. She had broken her leg nearly three months ago, and had to support herself on a crutch, but she had wished to come.

Mme. Guérard was just beginning to tell her about the drama of the hair when my name echoed through the room. “Mlle. Chara Bernhardt!” It was Leautaud, who later on was prompter at the Comédie Française, and who had a strong Auvergne accent. “Mlle. Chara Bernhardt!” I heard again, and I then sprang up without an idea in my mind and without uttering a word. I looked round for the pupil who was to give me my answers, and together we made our entry.

I was surprised at the sound of my voice, which I did not recognize. I had cried so much that it had affected my voice, and I spoke through my nose.

I heard a woman’s voice say:

“Poor child, she ought not to have been allowed to compete; she has an atrocious cold, her nose is running, and her face is swollen.”

I finished my scene, made my bow, and went away in the midst of very feeble and spiritless applause. I walked like a somnambulist, and on reaching Mme. Guérard and Mlle. De Brabender fainted away in their arms. Some one went to the hall in search of a doctor, and the rumor that “the little Bernhardt had fainted” reached my mother. She was sitting far back in a box bored to death.

When I came to myself again, I opened my eyes and saw my mother’s pretty face, with tears hanging on her long lashes. I laid my head against hers and cried quietly, but this time the tears were refreshing, not salt ones that burned my eyelids.

I stood up, shook out my dress, and looked at myself in the greenish mirror. I was certainly less ugly now, for my face was rested, my hair was once more soft and light, and altogether there was a general improvement in my appearance.

The tragedy competition was over, and the prizes had been awarded. I had no recompense at all, but my last year’s second prize had been mentioned. I felt confused, but it did not cause me any disappointment, as I had quite expected things to be like this. Several persons had protested in my favor. Camille Doucet, who was a member of the jury, had argued a long time for me to have a first prize in spite of my bad recitation. He said that my examination reports ought to be taken into account, and they were excellent; and then, too, I had the best class reports. Nothing, however, could overcome the bad effect produced that day by my nasal voice, my swollen face, and my heavy flakes of hair. After half an hour’s interval, during which I drank a glass of port wine and ate cakes, the signal was given for the comedy competition. I was down as the fourteenth for this, so that I had ample time to recover. My fighting instinct now began to take possession of me, and a sense of injustice made me feel rebellious. I had not deserved my prize that day, but it seemed to me that I ought to have received it nevertheless.

SARAH BERNHARDT IN THE HANDS OF HER COIFFEUR.

I made up my mind that I would have the first prize for comedy, and with the exaggeration that I have always put into everything, I began to get excited, and I said to myself that if I did not have the first prize I must give up the idea of the stage as a career. My love of mysticism and weakness for the convent came back to me more strongly than ever.

“Yes,” I said to myself, “I will go back to the convent, but only if I do not get the first prize”; and then the most foolish, illogical strike imaginable was waged in my weak, girl’s brain. I felt a genuine vocation for the convent when distressed about losing the prize, and a genuine vocation for the theater when I was hopeful about winning the prize.

With a very natural partiality I discovered in myself the gift of absolute self-sacrifice, renunciation, and devotion of every kind—qualities which would win for me easily the post of Mother Superior in the Grandchamps Convent. Then with the most indulgent generosity I attributed to myself all the necessary gifts for the fulfillment of my other dream, namely, to become the first, the most celebrated, and the most envied of actresses. I counted on my fingers all my qualities: gracefulness, charm, distinction, beauty, mystery, piquancy. Oh, yes, I found I had all these, and when my reason and my honesty raised any doubt or suggested a “but” to this fabulous inventory of my qualities, my combative and paradoxical ego at once found a plain decisive answer which admitted of no further argument.

It was under these special conditions and in this frame of mind that I went on to the stage when my turn came. The choice of my rôle for this competition was a very stupid one. I had to represent a married woman who was reasonable and given to reasoning, and I was a mere child, and looked much younger than I was. In spite of this, I was very brilliant; I argued well, was very gay, and had immense success. I was transfigured with joy and wildly excited, so sure I felt of a first prize.

I never doubted for a moment that it would be awarded to me unanimously. When the competition was over, the committee met to discuss the awards, and in the meantime I asked for something to eat. A cutlet was brought from the pastry cook patronized by the Conservatoire, and I devoured it, to the great joy of Mme. Guérard and Mlle. De Brabender, for I detested meat, and always refused to eat it.

The members of the committee at last went to their places in the state box, and there was silence in the hall. The young men were called first on to the stage. There was no first prize awarded to them. Parfouru’s name was called for the second prize for comedy. Parfouru is known to-day as M. Paul Porel, director of the Vaudeville Theater, and Réjane’s husband. After this came the turn for the girls.

I was in the doorway, ready to rush up to the stage. The words “first prize for comedy” were uttered, and I made a step forward, pushing aside a girl who was a head taller than I was. “First prize for comedy awarded unanimously to Mlle. Marie Lloyd.” The tall girl I had pushed aside now went forward, slender and beaming, toward the stage.

There were a few muttered protests, but her beauty, her distinction, and her modest charm won the day with everyone, and Marie Lloyd was cheered. She passed me on her return, and kissed me affectionately. We were great friends, and I liked her very, much, but I considered her a nonentity as a pupil. I do not remember whether she had received any prize the previous year, but certainly no one expected her to have one now, and I was simply petrified.

“Second prize for comedy: Mlle. Bernhardt.”

I had not heard this, and was pushed forward by my companions. On reaching the stage I bowed, and all the time I could see hundreds of Marie Lloyds dancing before me. Some of them were making grimaces, others were throwing me kisses—some were fanning themselves and others bowing. They were very tall, all these Marie Lloyds—too tall for the ceiling, and they walked over the heads of all the people and came toward me, crushing me, stifling me, so that I could not breathe. My face, it seems, was whiter than my dress.

On returning to the green room, I sat down without uttering a word and looked at Marie Lloyd, who was being made much of, and who was greatly complimented by everyone. She was wearing a pale blue tarlatan dress, with a bunch of forget-me-nots in the bodice and another in her black hair. She was very tall, and her delicate, white shoulders emerged modestly from her dress, which was cut very low, as for her this did not matter. Her refined face, with its somewhat proud expression, was charming and very beautiful. Although very young, she had more womanly charm than all of us. Her large brown eyes had a certain play in them, her little round mouth gave a smile which was full of mischief, and the nostrils of her wonderfully cut nose dilated. The oval of her beautiful face was intercepted by two little pearly, transparent ears of the most exquisite shape. She had a long, flexible white neck, and the pose of her head was charming. It was a beauty prize that the jury had conscientiously awarded to Marie Lloyd. She had come on the stage gay and fascinating, in her rôle of Célimène, and in spite of the monotony of her delivery, the carelessness of her elocution, the impersonality of her acting, she had carried off all the votes because she was the very personification of Célimène, that coquette of twenty years of age who was unconsciously so cruel. She had realized for everyone the ideal dreamed of by Molière.

All these thoughts shaped themselves later on in my brain, and this first lesson, which was so painful at the time, was of great service to m