CHAPTER VII

I MAKE MY DÉBUT AND EXIT

The next few days passed by without any particular events. I was working hard at Iphigénie, as M. Thierry had told me I was to make my début in this rôle.

At the end of August I received a notice requesting me to be at the rehearsal of Iphigénie. Oh, that first notice, how it made my heart beat! I could not sleep at night, and daylight did not come quickly enough for me. I kept getting up to look at the time. It seemed to me that the clock had stopped. I had dozed, and I fancied it was the same time as before. Finally, a streak of light coming through the windowpanes was, I thought, the triumphant sun illuminating my room. I got up at once, pulled back the curtains, and mumbled my rôle while dressing.

I thought of rehearsing with Mme. Devoyod, the first actress at the Comédie Française for tragedy, with Maubant, with ... I trembled as I thought of all this, for Mme. Devoyod was not supposed to be very indulgent. I arrived for the rehearsal an hour before the time. The stage manager, Davenne, smiled and asked me whether I knew my rôle.

“Oh, yes!” I exclaimed with conviction.

“Come and rehearse it. Would you like to?” and he took me to the stage.

I went with him through the long corridor of busts which leads from the foyer of the artistes to the stage. He told me the names of the celebrities represented by these busts. I stood still a moment before that of Adrienne Lecouvreur.

“I love that artiste,” I said.

“Do you know her story?” he asked.

“Yes, I have read all that has been written about her.”

“That’s quite right, my child,” said the worthy man. “You ought to read all that concerns your art. I will lend you some very interesting books.”

He took me on toward the stage. The mysterious gloom, the scenery reared up like fortifications, the bareness of the floor, the endless number of weights, ropes, trees, friezes, harrows overhead, the yawning house completely dark, the silence, broken by the creaking of the floor, and the vaultlike chill that one felt—all this together awed me. It did not seem to me to be part of that brilliant frame for the living artistes who every night won the applause of the house by their merriment or their sobs. No, I felt as though I were in the tomb of dead glories, and the stage seemed to me to be getting crowded with the illustrious ghosts of those whom the manager had just mentioned. With my highly strung nerves, my imagination, which was always evoking something, now saw them advance toward me, stretching out their hands. These specters wanted to take me away with them. I put my hands over my eyes and stood still.

“Are you not well?” asked M. Davenne.

“Oh, yes, thank you, it was just a little giddiness.”

His voice had chased away the specters, and I opened my eyes and paid attention to the worthy man’s advice. Book in hand, he explained to me where I was to stand, and my changes of place. He was rather pleased with my way of reciting, and he taught me a few of the traditions. At the line:

“Euripide à l’autel, conduisez la victime,” he said: “Mlle. Favart was very effective there....”

The artistes gradually began to arrive, grumbling more or less. They glanced at me, and then rehearsed their scenes without taking any further notice of me at all.

I felt inclined to cry, but I was more vexed than anything else. I heard a few words that sounded to me coarse, used by one or another of the artistes. I was not accustomed to such language, as at home everyone was rather scrupulous, and at my aunt’s a trifle affected, while at the convent it is unnecessary to say I had never heard a word that was out of place. It is true that I had been through the Conservatoire, but I had not associated intimately with any of the pupils, with the exception of Marie Lloyd and Rose Baretta, the elder sister of Blanche Baretta, who is now an associate of the Comédie Française.

When the rehearsal was over, it was decided that there should be another one at the same hour the following day, in the public foyer.

The costume maker came in search of me, as she wanted to try on my costume. Mlle. De Brabender, who had arrived during the rehearsal, went up with me to the costume room. She wanted my arms to be covered, but the costume maker told her gently that this was impossible for tragedy.

A dress of white woolen material was tried on me. It was very ugly, and the veil was so stiff that I refused it. A wreath of roses was tried on, but this, too, was so ugly that I refused to wear it.

“Well, then, mademoiselle,” said the costume maker dryly, “you will have to get these things and pay for them yourself, as this is the costume supplied by the Comédie.”

“Very well,” I answered, blushing, “I will get them myself.”

On returning home I told my mother my troubles, and, as she was always very generous, she promptly bought me a veil of white barège that fell in beautiful, large, soft folds, and a wreath of hedge roses which, at night, looked very soft and white. She also ordered me buskins from the shoemaker employed by the Comédie.

The next thing to think about was the make-up box. For this my mother had recourse to the mother of Dica Petit, my fellow student at the Conservatoire. I went with Mme. Dica Petit to M. Massin, a manufacturer of these make-up boxes. He was the father of Léontine Massin, another Conservatoire pupil.

We went up to the sixth floor of a house in the Rue Réamur, and on a plain-looking door read the words: “Massin, Manufacturer of Make-up Boxes.” I knocked and a little hunchback girl opened the door. I recognized Léontine’s sister, as she had come several times to the Conservatoire.

“Oh,” she exclaimed, “what a surprise for us! Titine,” she then called out, “here is Mlle. Sarah!”

Léontine Massin came running out of the next room. She was a pretty girl, very gentle and calm in demeanor. She threw her arms round me, exclaiming:

“How glad I am to see you! And so you are coming out at the Comédie. I saw it in the paper.”

I blushed up to my ears at the idea of being mentioned in the paper.

“I am engaged at the Variétés,” she said, and then she talked away at such a rate that I was bewildered. Mme. Petit did not enter into all this, and tried in vain to separate us. She had replied by a nod and an indifferent “Thanks” to Léontine’s inquiries about her daughter’s health. Finally, when the young girl had finished saying all she had to say, Mme. Petit remarked:

“You must order your box; we have come here for that, you know.”

“Ah! then you will find my father in his workshop at the end of the passage, and if you are not very long I shall still be here. I am going to rehearsal at the Variétés later on.”

Mme. Petit was furious, for she did not like Léontine Massin.

“Don’t wait, mademoiselle,” she said, “it will be impossible for us to stay afterwards.”

Léontine was annoyed, and, shrugging her shoulders, she turned her back on my companion. She then put her hat on, kissed me, and bowing gravely to Mme. Petit, remarked:

“Good-by, Mme. Gros-tas, and I hope I shall never see you again.” She then ran off, laughing merrily. I heard Mme. Petit mutter a few disagreeable words in Dutch, but I did not understand the meaning of them at the time. We then went to the workshop and found old Massin at his workbench, planing some small planks of white wood. His hunchback daughter kept coming in and out, humming gayly all the time. The father was glum and harassed, and had an anxious look. As soon as we had ordered the box we took our leave. Mme. Petit went out first and Léontine’s sister then put her hand into mine and said quietly:

“Father was not very polite, but it is because he is jealous. He wanted my sister to be at the Théâtre Français.”

I was rather disturbed by this confidence, and I had a vague idea of the painful drama which was acting so differently on the various members of this humble home.

On September 1, 1862, the day I was to make my début, I was in the Rue Duphot looking at the theatrical posters. They used to be put up then just at the corner of the Rue Duphot and the Rue St. Honoré. On the poster of the Comédie Française I read the words: “Début of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt.”... I have no idea how long I stood there, fascinated by the letters of my name, but I remember that it seemed to me as though every person who stopped to read the poster looked at me afterwards, and I blushed to the very roots of my hair.

At five o’clock I went to the theater. I had a dressing-room on the top floor which I shared with Mlle. Coblance. This room was on the other side of the Rue de Richelieu, in a house rented by the Comédie Française. A small covered bridge over the street served as a passage and means of communication for us to reach the theater.

I was a tremendously long time dressing, and did not know whether I looked nice or not. My petite dame thought I was too pale, and Mlle. De Brabender considered that I had too much color. My mother was to go direct to her seat in the theater, and Aunt Rosine was away in the country.

When we were told that the play was about to commence I broke out into a cold perspiration from head to foot, and felt ready to faint away. I went downstairs trembling, tottering, and my teeth chattering. When I arrived on the stage the curtain was being raised. That curtain, which was raised so slowly and solemnly, was, to me, like the veil being torn which was to let me have a glimpse of my future. A deep, gentle voice made me turn round. It was Provost, my first professor, who had come to encourage me. I greeted him warmly, so glad was I to see him again. Samson was there, too; I believe that he was playing that night in one of Molière’s comedies. The two men were very different. Provost was tall, his silvery hair was blown about, and he had a droll face. Samson was small, precise, dainty, his shiny white hair curled firmly and closely round his head. Both men had been moved by the same sentiment of protection for the poor, fragile, nervous girl, who was, nevertheless, so full of hope. Both of them knew my zeal for work, my obstinate will, which was always struggling for the victory over my physical weakness. They knew that my device “Quand-même” had not been adopted by me merely by chance, but that it was the outcome of a deliberate exercise of will power on my part. My mother had told them how I had chosen this device at the age of nine, after a formidable jump over a ditch which no one could jump, and which my young cousin had dared me to attempt. I had hurt my face, broken my wrist, and was in pain all over. While I was being carried home I exclaimed furiously: “Yes, I would do it again, quand-même, if anyone dared me again. And I will always do what I want to do all my life.” In the evening of that day, my aunt, who was grieved to see me in such pain, asked me what would give me any pleasure. My poor little body was all bandaged, but I jumped with joy at this, and quite consoled I whispered in a coaxing way: “I should like to have some writing paper with a motto of my own.”

My mother asked me rather slyly what my motto was. I did not answer for a minute, and then, as they were all waiting quietly, I uttered such a furious “Quand-même” that my Aunt Faure started back muttering, “What a terrible child!”

Samson and Provost reminded me of this story in order to give me courage; but my ears were buzzing so that I could not listen to them. Provost heard my catchword on the stage and pushed me gently forward. I made my entry and hurried toward Agamemnon, my father. I did not want to leave him again, as I felt I must have some one to hold on to. I then rushed to my mother, Clytemnestre. I got through my part, and on leaving the stage I tore up to my room and began to undress.

Mme. Guérard was terrified, and asked me if I was mad. I had only played in one scene and there were four more. I realized then that it would really be dangerous to give way to my nerves. I had recourse to my own motto, and, standing in front of the glass gazing into my own eyes, I ordered myself to be calm and to conquer myself, and my nerves, in a state of confusion, yielded to my brain. I got through the play, but was very insignificant in my part.

The next morning my mother sent for me early. She had been looking at Sarcey’s article in L’Opinion Nationale, and she now read me the following lines.... “Mlle. Bernhardt, who made her début yesterday in the rôle of Iphigénie, is a tall, pretty girl with a slender figure and a very pleasing expression, the upper part of her face is remarkably beautiful. She holds herself well, and her enunciation is perfectly clear. This is all that can be said for her at present.”

“The man is an idiot,” said my mother, drawing me to her. “You were charming.”

She then prepared a little cup of coffee for me, and made it with cream. I was happy, but not completely so. When my godfather arrived in the afternoon, he exclaimed:

“Good heavens! my poor child, what thin arms you have!”

As a matter of fact, people had laughed, and I had heard them, when, stretching out my arms, I had said the famous lines in which Favart had made her famous “effect” that was now a tradition. I certainly had made no “effect,” unless the smiles caused by my long, thin arms can be reckoned such.

My second appearance was in Valérie, when I did have some slight success.

My third appearance at the Comédie resulted in the following effusion from the pen of the same Sarcey:

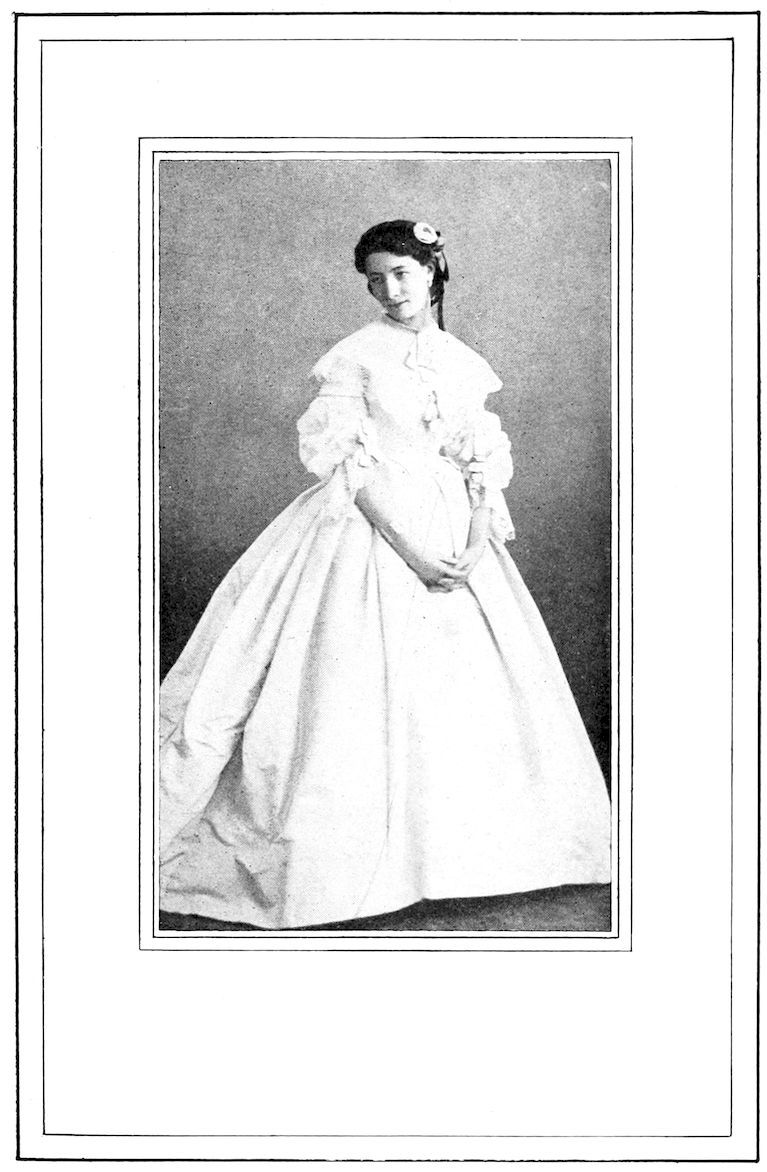

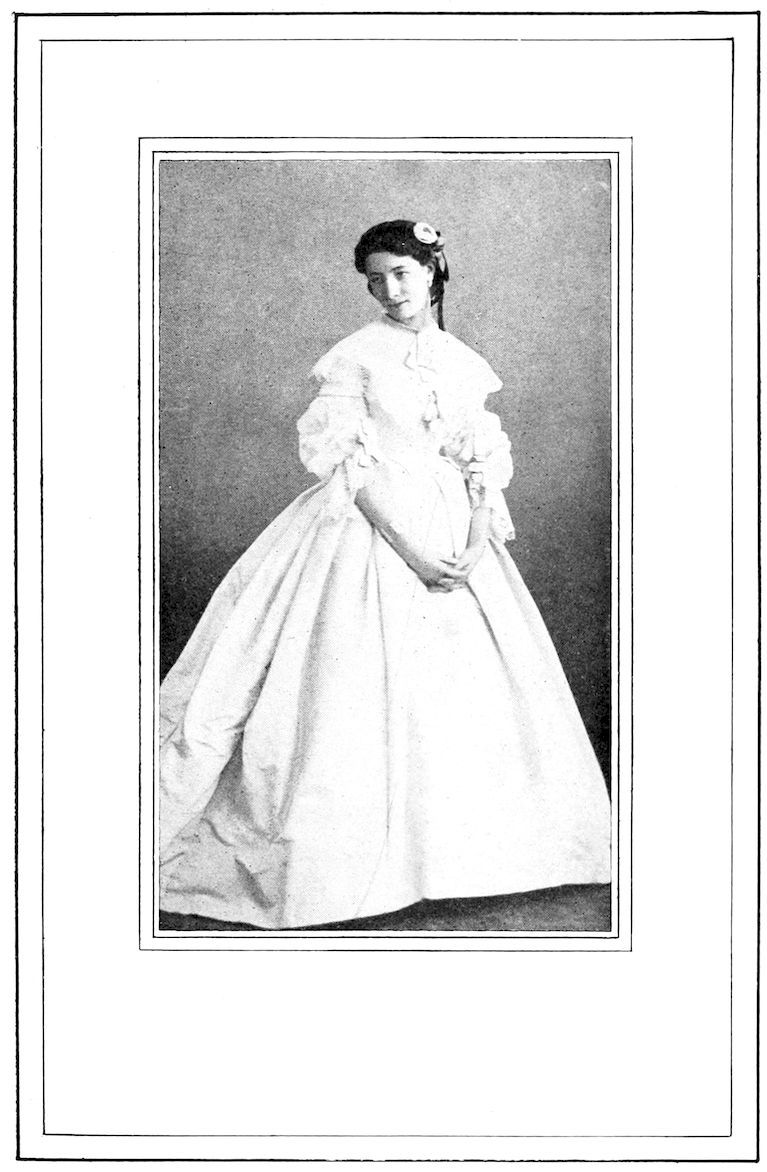

SARAH BERNHARDT AT THE TIME OF HER DÉBUT IN “LES FEMMES SAVANTES.”

L’Opinion Nationale, September 12th.... “The same evening ‘Les Femmes Savantes’ was given. This was Mlle. Bernhardt’s third appearance, and she took the rôle of Henriette. She was just as pretty and insignificant in this as in that of Junie (he had made a mistake, as it was Iphigénie I had played) and of Valérie, both of which rôles had been entrusted to her previously. This performance was a very poor affair, and gives rise to reflections by no means gay. That Mlle. Bernhardt should be insignificant does not so much matter. She is a débutante, and among the number presented to us it is only natural that some should be failures. The pitiful part is, though, that the comedians playing with her were not much better than she was, and they are Sociétaires of the Théâtre Français. All that they had more than their young comrade was a greater familiarity with the boards. They are just as Mlle. Bernhardt may be in twenty years’ time, if she stays at the Comédie Française.”

I did not stay there, though; for one of those nothings which change a whole life changed mine. I had entered the Comédie expecting to remain there always. I had heard my godfather explain to my mother all about the various stages of my career.

“The child will have so much during the first five years,” he said, “and so much afterwards, and then at the end of thirty years she will have the pension given to Associates, that is, if she ever becomes an Associate.” He appeared to have his doubts about this.

My sister Régina was the cause, though quite involuntarily this time, of the drama which made me leave the Comédie. It was Molière’s anniversary, and all the artistes of the Français had to salute the bust of the great writer, according to the tradition of the theater. It was to be my first appearance at a “ceremony” and my little sister, on hearing me tell about it at home, besought me to take her to it.

My mother gave me permission to do so, and our old Marguerite was to accompany us. All the members of the Comédie were assembled in the foyer. The men and women, dressed in different costumes, all wore the famous doctor’s cloak. The signal was given that the ceremony was about to commence, and everyone hurried to the corridor where the busts were. I was holding my little sister’s hand, and just in front of us was the very fat and very solemn Mme. Nathalie. She was a Sociétaire of the Comédie, old, spiteful, and surly.

Régina, in trying to avoid the train of Marie Roger’s cloak, stepped on to Nathalie’s, and the latter turned round and gave the child such a violent push that she was knocked against a column holding a bust. Régina screamed out, and, as she turned back to me, I saw that her pretty face was bleeding.

“You miserable creature!” I called out to the fat woman, and, as she turned round to reply, I slapped her in the face. She proceeded to faint; there was a great tumult, and an uproar of indignation, approval, stifled laughter, satisfied revenge, pity from those artistes who were mothers, for the poor child, etc. Two groups were formed, one around the wretched Nathalie, who was still in her swoon, and the other around little Régina. And the different aspect of these two groups was rather strange. Around Nathalie were cold, solemn-looking men and women fanning the fat, helpless lump with their handkerchiefs or fans. A young, but severe-looking Sociétaire was sprinkling her with drops of water. Nathalie, on feeling this, roused up suddenly, put her hands over her face and muttered in a far-away voice:

“How stupid! You’ll spoil my make-up!”

The younger men were stooping over Régina, washing her pretty face, and the child was saying in her broken voice:

“I did not do it on purpose, sister, I am certain I didn’t. She’s an old cow, and she just kicked for nothing at all!”

Régina was a fair-haired seraph who might have made the angels envious, for she had the most ideal and poetical beauty—but her language was by no means choice, and nothing in the world could change it. Her coarse speech made the friendly group burst out laughing, while all the members of the enemy’s camp shrugged their shoulders. Bressant, who was the most charming of the comedians and a general favorite, came up to me and said:

“We must arrange this little matter, mademoiselle, for Nathalie’s short arms are really very long. Between ourselves you were a trifle hasty, but I like that, and then that child is so droll and pretty,” he added, looking at my little sister.

The house was stamping with impatience, for this little scene had caused twenty minutes’ delay, and we were obliged to go on to the stage at once. Marie Roger kissed me, saying: “You are a plucky little comrade!” Rose Baretta drew me to her, murmuring: “How dared you do it! She is a Sociétaire!”

As for me, I was not very clear about what I had done, but my instinct warned me that I should pay dearly for it.

The following day I received a letter from the manager asking me to call at the Comédie at one o’clock about a matter concerning me privately. I had been crying all night long, more through nervous excitement than from remorse, and I was more particularly annoyed at the idea of the attacks I should have to endure from my own family. I did not let my mother see the letter, for from the day that I had entered the Comédie she had given me full liberty. I received my letters now direct, without her supervision, and I went about alone.

At one o’clock precisely I was shown into the manager’s office. M. Thierry, his nose more congested than ever, and his eyes more crafty, preached me a deadly sermon, blamed my want of discipline, absence of respect, and scandalous conduct, and finished his pitiful harangue by advising me to beg Mme. Nathalie’s pardon.

“I have asked her to come,” he added, “and you must apologize to her before three Sociétaires belonging to the Committee. Is she consents to forgive you the Committee will then consider whether to fine you or to cancel your engagement.”

I did not reply for a few minutes. I thought of my mother in distress, my godfather laughing in his bourgeois way, and my Aunt Faure triumphant, with her usual phrase: “That child is terrible!” I thought, too, of my beloved Brabender with her hands clasped, her mustache drooping sadly, her small eyes full of tears, so touching in their mute supplication. I could hear my gentle, timid Mme. Guérard arguing with everyone, so courageous she was always in her confidence in my future.

“Well, mademoiselle?” said M. Thierry curtly.

I looked at him without speaking and he began to get impatient.

“I will go and ask Mme. Nathalie to come here,” he said, “and I beg you will do your part as quickly as possible, for I have other things to attend to than to put your blunders right.”

“Oh, no, do not fetch Mme. Nathalie,” I said at last, “I shall not apologize to her. I will leave. I will cancel my engagement at once.”

He was stupefied, and his arrogance melted away in pity for the ungovernable, willful child who was about to ruin her whole future for the sake of a question of self-esteem. He was at once gentler and more polite. He asked me to sit down, which he had not hitherto done, and he sat down himself opposite to me and spoke to me gently about the advantages of the Comédie, and of the danger that there would be for me in leaving that illustrious theater which had done me the honor of admitting me. He gave me a hundred other very good, wise reasons which softened me. When he saw the effect he had made, he wanted to send for Mme. Nathalie, but I roused up then like a little wild animal.

“Oh, don’t let her come here, I should slap her again!” I exclaimed.

“Well, then, I must ask your mother to come,” he said.

“My mother would never come,” I replied.

“Then I will go and call on her.”

“It will be quite useless,” I persisted, “my mother has given me my liberty, and I am quite free to lead my own life. I alone am responsible for all that I do.”

“Well, then, mademoiselle, I will think it over,” he said rising to show me that the interview was at an end. I went back home determined to say nothing to my mother, but my little sister when questioned about her wound had told everything in her own way, exaggerating, if possible, the brutality of Mme. Nathalie and the audacity of what I had done. Rosa Baretta, too, had been to see me and had burst into tears, assuring my mother that my engagement would be canceled. The whole family was very much excited and distressed when I arrived, and when they began to argue with me it made me still more nervous. I did not take calmly the reproaches which one and another of them addressed to me, and I was not at all willing to follow their advice. I went to my room and locked myself in.

The following day no one spoke to me and I went up to Mme. Guérard to be comforted and consoled.

Several days passed by and I had nothing to do at the theater. Finally, one morning, I received a notice requesting me to be present for the reading of a play. It was “Dolorès,” by M. De Bornier. This was the first time I had been asked to the reading of a new piece. I was evidently to have the creation of a rôle. All my sorrows were at once dispersed like a cloud of butterflies. I told my mother of my joy, and she naturally concluded that as I was asked to go to a reading, my engagement was not to be canceled and I was not to be asked again to apologize to Mme. Nathalie.

I went to the theater, and to my utter surprise I received from M. Davennes the rôle of Dolorès, the chief part in Bornier’s play. I knew that Favart, who should have had this rôle, was not well, but there were other artistes for it, and I could not get over my joy and surprise. Nevertheless, I felt somewhat uneasy. A terrible presentiment has always warned me of any troubles about to come upon me.

I had been rehearsing for five days when one morning, on going upstairs, I suddenly found myself face to face with Nathalie, seated under Gérôme’s portrait of Rachel, known as “The Red Pimento.” I did not know whether to go downstairs again or to pass by. My hesitation was noticed by the spiteful woman.

“Oh, you can go by, mademoiselle,” she said. “I have forgiven you, as I have avenged myself. The rôle that you like so much is not to be left to you after all.”

I went by without uttering a word. I was thunderstruck by her speech, which I guessed would prove true.

I did not mention this incident to anyone, but continued rehearsing. It was on Tuesday that Nathalie had spoken to me, and on Friday I was disappointed to hear that Davennes was not there and that there was to be no rehearsal. Just as I was getting into my cab the hall porter ran out to give me a letter from Davennes. The poor man had not ventured to come himself and give me the news, which he was sure would be so painful to me.

He explained to me in his letter that on account of my extreme youth—the importance of the rôle—such responsibility for such young shoulders—as Mme. Favart had recovered from her illness, it was wiser, etc. I finished reading the letter through blinding tears, but very soon anger took the place of grief. I rushed back again and up to the manager’s office. He could not see me just then, but I said I would wait. At the end of an hour, thoroughly impatient, taking no notice of the office boy and the secretary, who wanted to prevent my entering, I opened the door of M. Thierry’s office and walked in. I was desperate, and all that anger with injustice and fury with falsehood could inspire me with, I let him have in a stream of eloquence only interrupted by my sobs. The manager gazed at me in bewilderment. He could not conceive of such daring and such violence in a girl so young.

When at last, thoroughly exhausted, I sank down on an armchair, he tried to calm me, but all in vain.

“I will leave at once,” I said. “Give me back my engagement and I will send you back mine.”

Finally, tired of argument and persuasion, he called his secretary in, gave him the necessary orders, and the latter soon brought in my engagement.

“Here is your mother’s signature, mademoiselle. I leave you free to bring it me back within forty-eight hours. After that time if I do not receive it I shall consider that you are no longer a member of the theater. But, believe me, you are acting unwisely. Think it over within the next forty-eight hours.”

I did not answer but went out of his office. That very evening I sent back to M. Thierry the engagement bearing his signature and tore up the one with that of my mother.

I had left Molière’s Theater and was not to re-enter it until twelve years later.