CHAPTER XVI

I LEAVE THE ODÉON

On returning home, I sat up a long time talking to Mme. Guérard, and when she wanted to go I begged her to stay longer. I had become so rich in hopes and future that I was afraid of thieves. My petite dame stayed on with me, and we talked till daybreak. At seven o’clock we took a cab and I drove my dear friend home, and then continued driving for another hour. I had already achieved a fair number of successes: “Le Passant,” and “Le Drame de la Rue de la Paix”; Anna Danby in “Kean,” and “Jean-Marie,” but I felt that the “Ruy Blas” success was greater than any of the others, and that this time I had become some one likely to be criticised, but not to be overlooked.

I often went in the morning to Victor Hugo’s and he was always very charming and kind.

When I was quite at my ease with him, I told him about my first impressions, about all my stupid, nervous rebellion with regard to him, about all that I had been told and all that I had believed, in my naïve ignorance about political matters.

On this particular morning, the master took great delight in my conversation. He sent for Mme. Drouet, the sweet soul, the companion of his glorious and rebellious mind. He told her, in a laughing, but melancholy way, about the evil work of bad people, in sowing error in every soil, whether favorable or not. That morning is engraved forever in my mind, for the great man talked a long time. Oh, it was not for me, but for what I represented in his eyes! Was I not, as a matter of fact, the young generation, in whom a bourgeois and clerical education had warped the intelligence, by closing the mind to every generous idea, to every flight toward the New?

When I left Victor Hugo that morning I felt myself more worthy of his friendship.

I then went to Girardin’s, as I wanted to talk to some being who loved the poet, but he was out.

I went next to Marshal Canrobert’s, and there I had a great surprise. Just as I was getting out of the carriage, I nearly fell into the arms of the marshal, who was coming out of his house.

“What is it? What’s the matter? Is it postponed?” he asked laughing.

I did not understand and gazed at him rather bewildered. “Well, have you forgotten that you invited me to luncheon?” he asked.

I was quite confused, for I had entirely forgotten it. “Well, all the better!” I said. “I very much wanted to talk to you. Come, I am going to take you with me now.”

I then described my visit to Victor Hugo, and repeated all the fine things he had said to me, forgetting that I was constantly saying things that were contrary to his ideas. This admirable man could admire, though, and if he could not change his opinions, he approved the great ideas which were to bring about great changes.

One day, when he and Busnach were both at my house, there had been a political discussion which became rather violent. I was afraid for a moment that things might take a wrong turn, as Busnach was the most witty, and at the same time the rudest man in France.... It is only fair to say, though, that if Marshal Canrobert was a polite man and very well bred, he was not at all behind William Busnach in wit. The latter was worked up by the teasing speeches of the marshal.

“I challenge you, monsieur,” he exclaimed, “to write about the odious Utopias that you have just been supporting!” “Oh, M. Busnach,” replied Canrobert, coldly, “we do not use the same steel for writing history! You use a pen and I a sword.”

The luncheon that I had so completely forgotten was nevertheless a luncheon arranged several days previously. On reaching home we found there Paul de Rémusat, charming Mlle. Hocquigny, and M. De Montbel, a young attaché of the Embassy. I explained my lateness as well as I could and the morning finished in the most delicious harmony of ideas.

I have never felt more than I did that day the infinite joy of listening.

During a silence, Mlle. Hocquigny turned to the marshal and said: “Are you not of the opinion that our young friend ought to enter the Comédie Française?”

“Ah, no, no!” I exclaimed, “I am so happy at the Odéon. I began at the Comédie and the short time I stayed there I was so unhappy.”

“You will be obliged to go back there, my dear friend—obliged! Believe me, it will be better early than late.”

“Well, do not spoil to-day’s pleasure for me, for I have never been happier!”

One morning after this my maid brought me a letter. The large round stamp, on which the words “Comédie Française” are to be read, was on the corner of the envelope.

I remembered that just ten years ago that very day, our old servant Marguerite had, without my mother’s permission, handed me a letter in the same kind of envelope. My face then had flushed with joy, but this time I felt a faint tinge of pallor touch my cheeks. When events occur which disturb my life, I always have a movement of recoil toward the past. I cling for a second to what is, and then I fling myself headlong into what is to be. It is like a gymnast who clings first to his trapeze bar in order to fling himself afterwards with full force into space. In one second the “now” becomes for me the “has been,” and I love it with tender emotion as something dead. But I adore what is to be without seeking even to know about it, for what is to be is the unknown, the mysterious attraction. I always fancy that it will be something unheard of, and I shudder from head to foot in delicious uneasiness.

I receive quantities of letters, and it seems to me that I never receive enough. I watch them accumulating just as I watch the waves of the sea. What are they going to bring me, these mysterious envelopes, large, small, pink, blue, yellow, white? What are they going to fling upon the rock, these great wild waves, dark with seaweed? What sailor-boy’s corpse? What remains of a wreck? What are these little brisk waves going to leave on the beach, these reflections of a blue sky, little laughing waves? What pink “seastar”? What mauve anemone? What pearly shell?

So I never open my letters immediately. I look at the envelopes, try to recognize the handwriting, the seal, and it is only when I am quite certain from whom the letter comes that I open it. The others I leave my secretary to open or a kind friend, Suzanne Leylor. My friends know this so well that they always put their initials in the corner of their envelopes. At that time, I had no secretary, but my petite dame served me as such. I looked at the envelope a long time and gave it at last to Mme. Guérard.

“It is a letter from M. Perrin, director of the ‘Comédie Française,’” she said. “He asks if you can fix a time to see him on Tuesday or Wednesday afternoon at the ‘Comédie Française,’ or at your own house.”

“Thanks, what day is it to-day?” I asked.

“Monday,” she replied.

I then installed Mme. Guérard at my desk and asked her to reply that I would go there the following day at three o’clock.

I was earning very little at that time at the Odéon. I was living on what my father had left me, that is, on the transaction made by the Hâvre notary, and not much remained. I therefore went to see Duquesnel and showed him the letter.

“Well, what are you going to do?” he asked.

“Nothing. I have come to ask your advice.”

“Oh, well, I shall advise you to stay at the Odéon! Besides, your engagement does not terminate for another year, and I shall not let you leave!”

“Well, raise my salary, then,” I said. “I am offered twelve thousand francs a year at the Comédie. Give me fifteen thousand here and I will stay, for I do not want to leave.”

“Listen to me,” said the charming manager in a friendly way. “You know that I am not free to act alone, but I will do my best, I promise you,” and Duquesnel certainly kept his word. “Come here to-morrow before going to the Comédie, and I will give you Chilly’s reply. But take my advice and if he obstinately refuses to increase your salary, do not leave, we shall find a way. And besides ... anyhow, I cannot say any more!”

I returned the following day according to arrangement. I found Duquesnel and Chilly in the manager’s office. Chilly began at once somewhat roughly: “And so you want to leave, Duquesnel tells me. Where are you going? It is most stupid, for your place is here. Just consider and think it over for yourself. At the Gymnase they only give modern pieces, pieces for dressy plays. That is not your style. At the Vaudeville it is the same. At the Gaieté you would spoil your voice. You are too distinguished for the Ambigu.”

I looked at him without replying and he felt awkward and mumbled:

“Well, then, you are of my opinion?”

“No,” I answered, “you have forgotten the Comédie.”

He was sitting in his big armchair and he burst out laughing.

“Ah, no, my dear girl!” he said, “you must not tell me that! They’ve had enough of your queer character at the Comédie. I dined the other night with Maubant and when some one said that you ought to be engaged at the Comédie Française he nearly choked with rage. I can assure you he did not show much affection as far as you were concerned, the great tragedian!”

“Oh, well, you ought to have taken my part!” I exclaimed, irritated. “You know very well that I am very reliable.”

“But I did take your part,” he said, “and I added even that it would be a very fortunate thing for the Comédie if it could have an artiste with your will power, that perhaps might relieve the monotonous tone of the house, and I only spoke as I thought, but the poor tragedian was beside himself. He does not consider that you have any talent. In the first place, he maintains that you do not know how to recite poetry. He declares that you make all your A’s too broad. Finally, when he had no arguments left, he declared that as long as he lives you will never enter the Comédie Française.”

I was silent for a moment, weighing the pros and cons of the probable result of my experiment. Finally coming to a decision, I murmured somewhat waveringly: “Well, then, you will not give me a higher salary?”

“No, a thousand times no!” yelled Chilly. “You will try to make me sing when your engagement comes to an end and then we will see. But I have your signature until then. You have mine, too, and I hold to our engagement. The Théâtre Français is the only one that would suit you besides ours, and I am quite easy in my mind with regard to that theater.”

“You make a mistake, perhaps,” I answered. He got up brusquely and came and stood opposite me, his two hands in his pockets. He then said in an odious and familiar tone: “Ah! that’s it, is it? You think I am an idiot, then?”

I got up, too, and said coldly, pushing him gently back: “I think you are a triple idiot.” I then hurried away toward the staircase, and all Duquesnel’s shouting was in vain. I ran down the stairs two at a time.

On arriving under the Odéon Arcade I was stopped by Paul Maurice, who was just going to invite Duquesnel and Chilly for Victor Hugo to a supper to celebrate the hundredth presentation of “Ruy Blas.”

“I have just come away from your house,” he said. “I have left you a few lines from Victor Hugo.”

“Good, good, that’s all right,” I replied, getting into my carriage. “I shall see you to-morrow, then, my friend.”

“Good heavens, what a hurry you are in!” he said.

“Yes!” I replied; and then, leaning out of the window, I said to my coachman: “Drive to the Comédie Française.”

I looked at Paul Maurice to wish him farewell. He was standing stupefied on the arcade steps.

On arriving at the Comédie I sent my card to Perrin, and five minutes later was ushered in to that icy manikin. There were two very distinct personages in this man. The one was the man he was himself, and the other the one he had created for the requirements of his profession. Perrin himself was gallant, pleasant, witty, and slightly timid; the manikin was cold and somewhat given to posing.

I was first received by Perrin, the manikin. He was standing up, his head bent to bow to a woman, his arm outstretched to indicate the hospitable armchair. He waited, with a certain affectation, until I was seated, before sitting down himself. He then picked up a paper knife, in order to have something to do with his hands, and in a rather weak voice, the voice of the manikin, he remarked:

“Have you thought it over, mademoiselle?”

“Yes, monsieur, and here I am to give my signature.”

Before he had time to give me any encouragement to dabble with the things on his desk, I drew up my chair, picked up a pen and prepared to sign the paper. I did not take enough ink at first, and I stretched my arm out across the whole width of the writing table and dipped my pen this time resolutely to the bottom of the ink pot. I took too much ink, however, this time, and on the return journey a huge drop of it fell on the large sheet of white paper in front of the manikin. He bent his head, for he was slightly shortsighted, and looked for a moment like a bird when it discovers a hempseed in its grain. He then proceeded to put aside the blotted sheet.

“Wait a minute! oh, wait a minute!” I exclaimed, seizing the inky paper. “I want to see whether I am doing right or not to sign. If that is a butterfly I am right, and if anything else, no matter what, I am wrong.” I took the sheet, doubled it in the middle of the enormous blot and pressed it firmly together. Emile Perrin thereupon began to laugh, giving up his manikin attitude entirely. He leaned over to examine the paper with me, and we opened it very gently, just as one opens one’s hand after imprisoning a fly. When the paper was spread open, in the midst of its whiteness, a magnificent black butterfly with outspread wings was to be seen.

“Well, then,” said Perrin, with nothing of the manikin left, “we were quite right in signing.”

After this we talked for some time, like two friends who meet again, for this man was charming and very fascinating in spite of his ugliness. When I left him we were friends and delighted with each other.

I was playing “Ruy Blas” that night at the Odéon. Toward ten o’clock Duquesnel came to my dressing-room.

“You were rather rough on that poor Chilly,” he said. “And then, too, you really were not nice. You ought to have come back when I called you. Is it true, as Paul Maurice tells us, that you went straight to the Théâtre Française?”

“Here, read for yourself,” I said, handing him my engagement with the Comédie.

Duquesnel took the paper and read it.

“Will you let me show it to Chilly?” he asked.

“Show it him, certainly,” I replied.

He came nearer and said in a grave, hurt tone:

“You ought never to have done that without telling me first. It shows a lack of confidence, and I did not deserve that.”

He was right, but the thing was done. A moment later Chilly arrived, furious, gesticulating, shouting, stammering in his anger.

“It is abominable!” he said. “It is treason, and you had not even the right to do it! I shall make you pay damages!”

As I felt in a bad humor, I turned my back on him and excused myself in as poor a way as possible to Duquesnel. He was hurt, and I was a little ashamed, for this man had given me nothing but proofs of kindliness; and it was he who, in spite of Chilly and many other unwilling people, had held the door open for my future.

Chilly kept his word and brought an action against me and the Comédie. I lost and had to pay six thousand francs damage to the managers of the Odéon.

A few months later Victor Hugo invited the interpreters of “Ruy Blas” to a big supper in honor of the one hundredth performance. This was a great delight to me, as I had never been present at a supper of this kind.

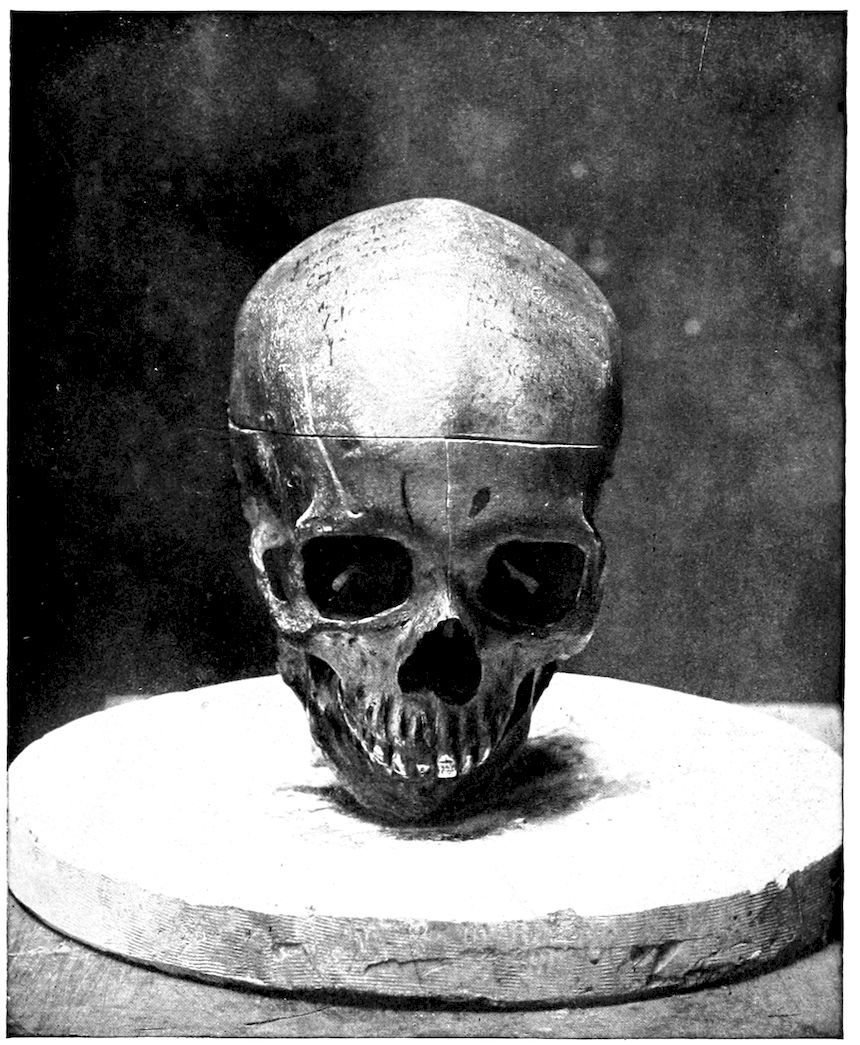

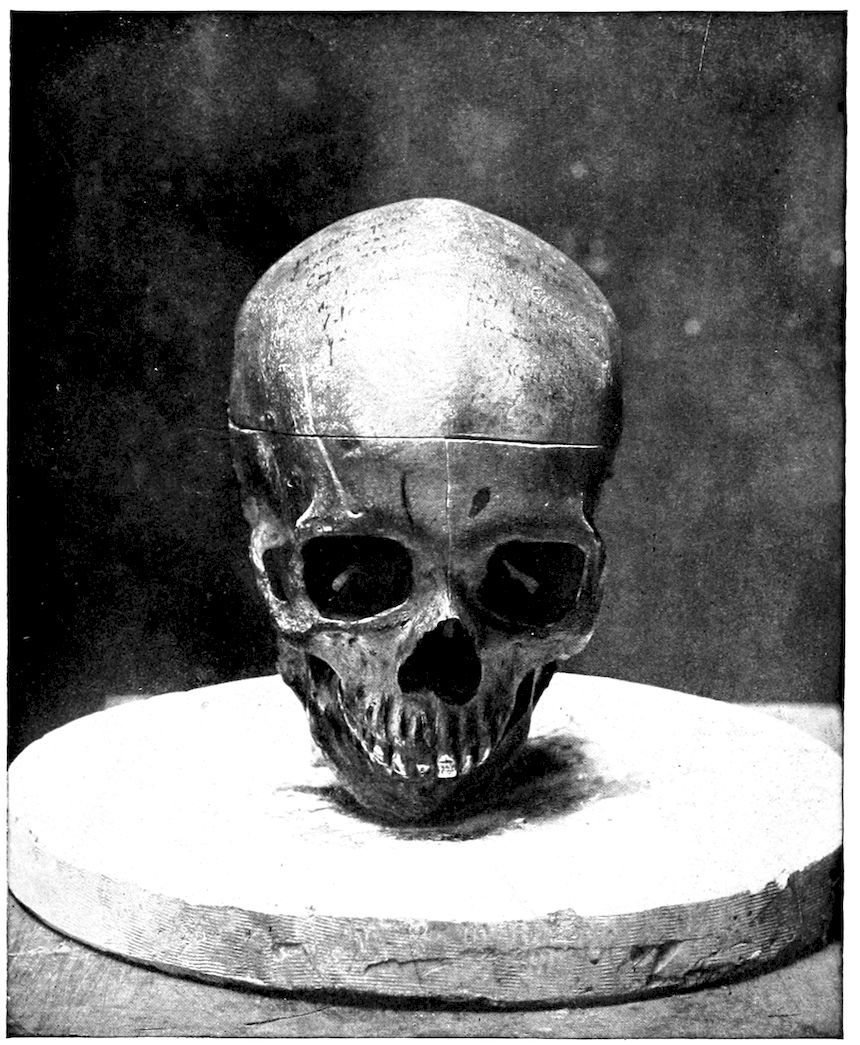

SKULL IN MADAME BERNHARDT’S LIBRARY, WITH AUTOGRAPH VERSES BY VICTOR HUGO.

I had scarcely spoken to Chilly since our last scene. On the night in question he was placed at my right, and we had to get reconciled. I was seated at the right of Victor Hugo, and at his left was Mme. Lambquin, who was playing the Camerara Mayor. Duquesnel was next to Mme. Lambquin. Opposite the illustrious poet was another poet, Théophile Gautier, with his lion’s head on an elephant’s body. He had a brilliant mind and said the choicest things with a horse laugh. The flesh of his fat, flabby, wan face was pierced by two eyes veiled by heavy lids. The expression of them was charming, but far away. There was in this man an Oriental nobility choked by Western fashion and customs. I knew nearly all his poetry, and I gazed at him with affection, the fond lover of the Beautiful.

It amused me to imagine him dressed in superb Oriental costumes. I could see him lying down on huge cushions, his beautiful hands playing with gems of all colors, and some of his verses came in murmurs to my lips. I was just setting off with him in a dream that was infinite, when a word from my neighbor, Victor Hugo, made me turn toward him. What a difference! He was just himself, the great poet, the most ordinary of beings, except for his luminous forehead. He was heavy looking, although very active. His nose was common, his eyes lewd, and his mouth without any beauty; his voice alone had nobility and charm. I liked to listen to him while looking at Théophile Gautier.

I was a little embarrassed, though, when I looked across the table, for at the side of the poet was an odious individual, Paul de Ste. Victor. His cheeks looked like two bladders from which the oil was oozing out. His nose was sharp and like a crow’s beak, his eyes evil looking and hard, his arms too short, and he was too stout. He had plenty of wit and talent, but he employed both in saying and writing more harm than good. I knew that this man hated me, and I promptly returned him hatred for hatred.

In the toast proposed by Victor Hugo in thanking everyone for such zealous help on the reappearance of his work, every person raised his glass and looked toward the poet, but the illustrious master turned toward me and continued: “As to you, madame——” Just at this moment Paul de St. Victor put his glass down so violently on the table that it broke. There was an instant of stupor, and then I leaned across the table and held my glass out toward Paul de St. Victor.

“Take mine,” I said, “monsieur, and then when you drink you will know what my thoughts are in reply to yours, which you have just expressed so clearly!”

The horrid man took my glass, but with what a look!

Victor Hugo finished his speech in the midst of applause and cheers. Duquesnel then leaned back and spoke to me quietly. He asked me to tell Chilly to reply, that it was his turn to speak.

“Come, get up,” I said to him. He gazed at me with a glassy look and in a far-away voice replied:

“My legs are being held.” I looked at him more attentively, while Duquesnel asked for silence for M. De Chilly’s speech. I saw that his fingers were grasping a fork desperately, the tips of his fingers were white, the rest of the hand was violet. I took his hand, and it was icy cold, the other was hanging down inert under the table. There was silence and all eyes turned toward Chilly.

“Get up,” I said, seized with terror. He made a movement, and his head suddenly fell forward with his face on his plate. There was a muffled uproar, and the few women present surrounded the poor man. Stupid, commonplace, indifferent things were uttered in the same way that one mutters familiar prayers. His son was sent for, and then two of the waiters came and carried the body away, living, but inert, and placed it in a small drawing-room.

Duquesnel stayed with him, begging me, however, to go back to the poet’s guests. I returned to the room where the supper had taken place. Groups had been formed, and when I was seen entering I was asked if he was no better.

“The doctor has just arrived and he cannot yet say,” I replied.

“It is indigestion,” said Lafontaine (Ruy Blas), tossing off a glass of liqueur brandy.

“It is cerebral anæmia,” pronounced Tallien (Don Guritan) clumsily, for he was always losing his memory.

Victor Hugo approached and said very simply:

“It is a beautiful kind of death.”

He then took my arm and led me away to the other end of the room, trying to chase my sadness away by gallant and poetical whispers. Some little time passed with this gloom weighing on us, and then Duquesnel returned. He was pale, but had put on the attitude of a man of the world, and was ready to answer all questions.

“Oh, yes, he had just been taken home. It would be nothing, it appeared. He only needed rest for a couple of days. Probably his feet had been cold during the meal.”

“Yes,” put in one of the “Ruy Blas” guests, “there certainly was a fine draught from some chink under the table!”

“Yes,” Duquesnel was just replying to some one who was worrying him. “Yes, no doubt, there was too much heat for his head.”

“Yes,” added another of the guests, “our heads were nearly on fire with that wretched gas.”

I could see the moment arriving when Victor Hugo would be reproached by all of his guests for the cold, the heat, the food, and the wine of his banquet. All these imbecile remarks got on Duquesnel’s nerves. He shrugged his shoulders, and drawing me away from the crowd said:

“It’s all over with him.”

I had had a presentiment of this, but the certainty of it now caused me intense grief.

“I want to go,” I said to Duquesnel. “Would you kindly tell some one to ask for my carriage?”

I moved toward the small drawing-room which served as a cloak room for our wraps, and there old Mme. Lambquin knocked up against me. Slightly intoxicated by the heat and the wine, she was waltzing with Tallien.

“Ah! I beg your pardon, little Madonna,” she said, “I nearly knocked you over.”

I pulled her toward me and, without reflecting, whispered to her, “Don’t dance any more, Mamma Lambquin, Chilly is dying.” She was purple, but her face turned as white as chalk. Her teeth began to chatter, but she did not utter a word.

“Oh, my dear Lambquin,” I murmured, “I did not know I should make you so wretched!”

But she was not listening to me any longer. She was putting on her cloak.

“Are you leaving?” she asked me.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Will you drive me home? I will then tell you....”

She wrapped a black fichu round her head and we both went downstairs, accompanied by Duquesnel and Paul Maurice, who saw us into the carriage.

She lived in the St. Germain neighborhood and I in the Rue de Rome. On the way the poor woman told me the following details:

“You know, my dear,” she began, “I have a mania for somnambulists, and fortune tellers of all kinds. Well, last Friday (you see, I only consult them on a Friday) a woman who tells fortunes by cards said to me: ‘You will die a week after a man who is dark and not young and whose life is connected with yours.’ Well, my dear, I thought she was just making game, for there is no man whose life is connected with mine, as I am a widow and have never had any liaison. I therefore abused her for this, as I paid her seven francs. She charges ten francs to other people but seven francs to artistes. She was furious at my not believing her, and she seized my hands and said: ‘It’s no good yelling at me, for it is as I say. And if you want me to tell you the exact truth, it is a man who supports you, and even to be more exact still, there are two men who support you, the one dark and the other fair—It’s a nice thing, that!’ She had not finished her speech before I had given her such a slap as she had never had in her life, I can assure you. Afterwards, though, I puzzled my head to find out what the wretched woman could have meant. And all I could find was that the two men who support me, the one dark and the other fair, are our two managers: Chilly and Duquesnel. And, now you tell me that Chilly——”

She stopped short, breathless with her story, and again seized with terror. “I feel stifled,” she murmured, and, in spite of the freezing cold, we lowered both the windows. On arriving I helped her up her four flights of stairs and after telling the concierge to look after her, and giving the woman a twenty-franc piece to make sure that she would do so, I went home myself very much upset by all these incidents, as dramatic as they were unexpected, in the midst of a fête.

Three days later Chilly died without ever recovering consciousness.

Twelve days later poor Lambquin died. To the priest who gave her absolution she said: “I am dying because I listened to and believed the demon.”