CHAPTER XVII

I RETURN TO THE COMÉDIE FRANÇAISE

I left the Odéon with very great regret, for I adored and still adore that theater. It always seems as though in itself it were a little provincial town. Its hospitable arcades, under which so many poor old savants take the air and are sheltered at the same time from the sun; the large flags all round, between the crevices of which microscopic yellow grass grows; its tall pillars, blackened by time, by hands, and by the dirt from the road; the uninterrupted noise going on all around, the departure of the omnibuses, like the departure of the old coaches; the fraternity of the people who meet there, everything, even to the very railings of the Luxembourg, give it a quite special aspect in the midst of Paris. Then, too, there is a kind of odor of the colleges there, the very walls are impregnated with youthful hopes. People are not always talking there of yesterday as they do in the other theaters. The young artistes who come there talk of to-morrow.

In short, my mind never goes back to those few years of my life without a childish emotion, without thinking of laughter and without a dilation of the nostrils, inhaling again the odor of little ordinary bouquets, clumsily tied up, bouquets which had all the freshness of flowers that grow in the open air, flowers that were the offerings of the hearts of twenty summers, little bouquets paid for out of the purses of students.

I would not take anything away with me from the Odéon. I left the furniture of my dressing-room to a young artiste. I left my costumes, all the little toilette knickknacks. I divided them and gave them away. I felt that my life of hopes and dreams was to cease there. I felt that the ground was now ready for the fruition of all the dreams, that life was about to commence, and I divined rightly.

My first experience at the Comédie Française had not been a success. I knew that I was going into the lion’s den. I counted few friends in this house, except Laroche, Coquelin, and Mounet-Sully; the two first my friends of the Conservatoire, and the latter of the Odéon. Among the women Marie Lloyd and Sophie Croizette, both friends of my childhood, the disagreeable Jouassain, who was nice only to me, and the adorable Mlle. Brohan, whose goodness delighted the soul, whose wit charmed the mind, and whose indifference rebuffed devotion.

M. Perrin decided that I should make my début in “Mademoiselle de Belle Isle,” according to Sarcey’s wish. The rehearsals began in the foyer, which troubled me very much. Mlle. Brohan was to play the part of the Marquise de Prie. At this time she was so fat as to be almost unsightly, while I was so thin that the composers of popular and comic verses took my meager proportions as their theme and the cartoonists as a subject for their albums. It was therefore impossible for the Duc de Richelieu to mistake the Marquise de Prie (Madeleine Brohan) for Mademoiselle de Belle Isle (Sarah Bernhardt) in the inconvenient and conclusive nocturnal rendezvous given by the Marquise to the Duc, who thinks he embraces the chaste Mademoiselle de Belle Isle.

At each rehearsal, Bressant, who took the part of the Duc de Richelieu, would stop, saying: “No, it is too ridiculous. I must play the Duc de Richelieu with both my arms cut off!” And Madeleine left the rehearsal to go to the director’s room, in order to try and get rid of the rôle.

This was exactly what Perrin wanted; he had from the earliest moment thought of Croizette, but he wanted to have his hand forced for private and underhand reasons which he knew and which others guessed.

At last the change took place, and the serious rehearsals commenced. Then the first performance was announced for November 6 (1872). I have always had, from the very beginning, and still have, a terrible fear, especially when I know that much is expected from me. And I knew a long time beforehand that the Salle had been let; I knew that the Press counted on a big success, and that Perrin himself was reckoning on a succession of good takings.

Alas! all these hopes and predictions went for nothing, and my débuts at the Comédie Française were only mediocre.

The following is an extract from the Temps of November 11, 1872. It was written by Francisque Sarcey, with whom I was not then acquainted, but who was following my career with very great interest:

“It was a very brilliant assembly, as this début had attracted all theater lovers. The fact is, besides the special merit of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt, a whole crowd of true or false stories had been circulated about her personally, and all this had excited the curiosity of the Parisian public. Her appearance was a disappointment. She had, by her costume, exaggerated in a most ostentatious way a slenderness which is elegant under the veils and ample drapery of the Grecian and Roman heroines, but which is objectionable in modern dress. Then, too, either powder does not suit her, or stage fright had made her terribly pale. The effect of this long, white face emerging from a long, black sheath was certainly unpleasant” (I looked like an ant), “particularly as the eyes had lost their brilliancy, and all that relieved the face were the sparkling white teeth. She went through the first three acts with a convulsive tremor, and we recognized the Sarah of ‘Ruy Blas’ only by two couplets which she gave in her enchanting voice with the most wonderful grace; but in all the more powerful passages she was a failure. I doubt whether Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt will ever, with her delicious voice, be able to render those deep, thrilling notes, expressive of paroxysms of violent passion, which are capable of carrying away an audience. If only nature had endowed her with this gift, she would be a perfect artiste, and there are none such on the stage. Roused by the coldness of her public, Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt was entirely herself in the fifth act. This was certainly our Sarah once more, the Sarah of ‘Ruy Blas,’ whom we had admired so much at the Odéon,” etc., etc.

As Sarcey said, I made a complete failure of my début. My excuse, though, was not the “stage fright” to which he attributed it, but the terrible anxiety I felt on seeing my mother hurriedly leave her seat in the dress circle five minutes after my appearance on the stage. I had glanced at her on entering, and had noticed her deathlike pallor. When she went out, I felt that she was about to have one of those attacks which endangered her life, so that my first act seemed to me interminable. I uttered one word after another, stammering through my sentences haphazard, with only one idea in my head, a longing to know what had happened. Oh, the public cannot conceive of the tortures endured by the unfortunate comedians who are there before them in flesh and blood on the stage, gesticulating and uttering phrases, while their heart, all torn with anguish, is with the beloved absent one who is suffering! As a rule, one can fling away the worries and anxieties of everyday life, put off one’s own personality for a few hours, take on another and, forgetting everything else, enter as it were into another life. But that is impossible when our dear ones are suffering; anxiety then lays hold of us, attenuating the bright side, magnifying the dark, maddening our brain, which is living two lives at once, and tormenting our heart, which is beating as though it would burst. These were the sensations I experienced during that first act.

“Mamma? What has happened to mamma?” were my first words on leaving the stage. No one could tell me anything.

Croizette came up to me and said: “What’s the matter? I hardly recognize you, and you weren’t yourself at all just now in the play.”

In a few words I told her what I had seen, and all that I had felt. Frédéric Febvre sent at once to get news, and the doctor came hurrying to me.

“Your mother had a fainting fit, mademoiselle,” he said, “but they have just taken her home.”

“It was her heart, wasn’t it?” I asked, looking at him.

“Yes,” he replied, “madame’s heart is in a very agitated state.”

“Oh, I know how ill she is!” I said, and not being able to control myself any longer, I burst into sobs. Croizette helped me back to my dressing-room. She was very kind, for we had known each other from childhood, and were very fond of each other. Nothing ever estranged us, in spite of all the malicious gossip of envious people, and all the little miseries due to vanity.

My dear Mme. Guérard (ma petite dame) took a cab and hurried away to my mother to get news for me. I put a little more powder on, but the public, not knowing what was taking place, were annoyed with me, thinking I was guilty of some fresh caprice, and received me still more coldly than before. It was all the same to me, as I was thinking of something else. I went on saying Mademoiselle de Belle Isle’s words (a most stupid and tiresome rôle), but all the time, I, Sarah, was waiting for news about my mother. I was watching for the return of ma petite dame. “Open the door on the O. P. side, just a little way,” I had said to her, “and make a sign like this, if mamma is better, and like that, if she is worse.” But I had forgotten which of the signs was to stand for better, and when, at the end of the third act, I saw Mme. Guérard opening the door and nodding her head for “yes,” I became quite idiotic. It was in the big scene of the third act when Mademoiselle de Belle Isle reproaches the Duc de Richelieu (Bressant) with doing her such irreparable harm. The Duc replies, “Why did you not say that some one was listening, that some one was hidden?” I exclaimed: “It’s Guérard bringing me news!” The public had not time to understand, for Bressant went on quickly, and so saved the situation.

After an unenthusiastic recall, I heard that my mother was better, but that she had had a very serious attack. Poor mamma, she had thought me such a fright when I made my appearance on the stage that her superb indifference had given way to grievous astonishment, and that, in its turn, to rage, on hearing a lady seated near her say in a jeering tone: “Why, she’s like a dried bone, this little Bernhardt!”

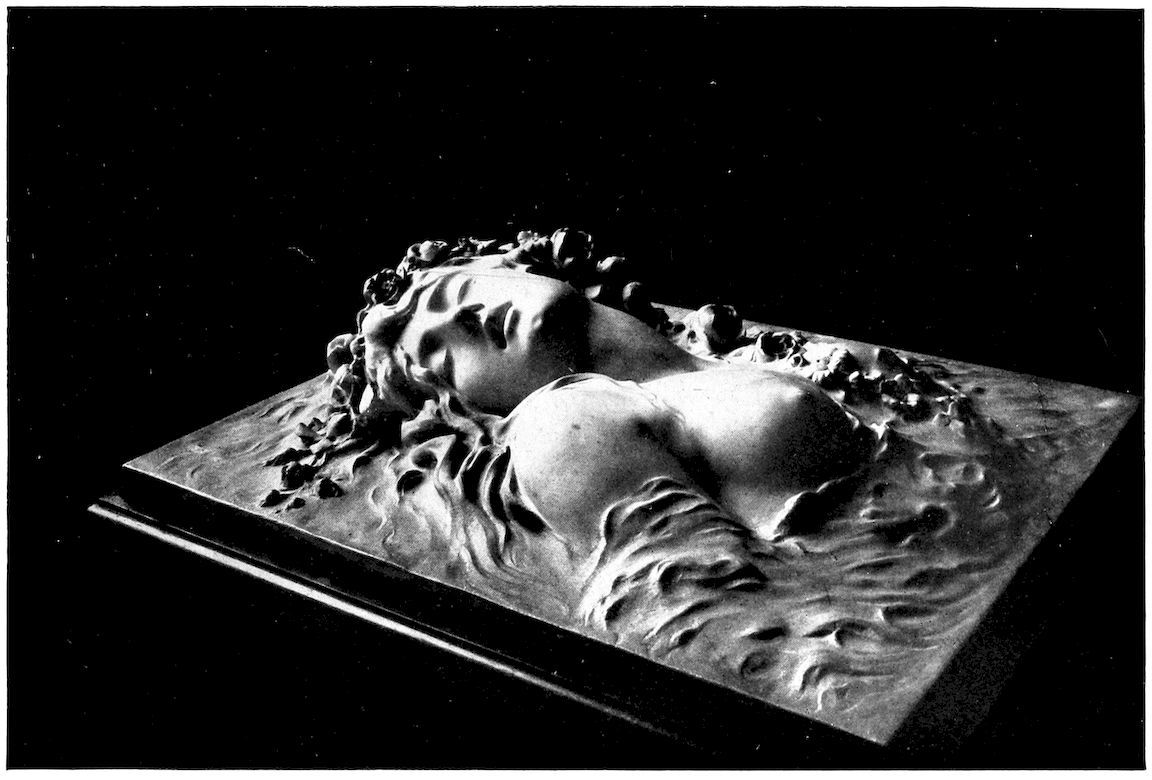

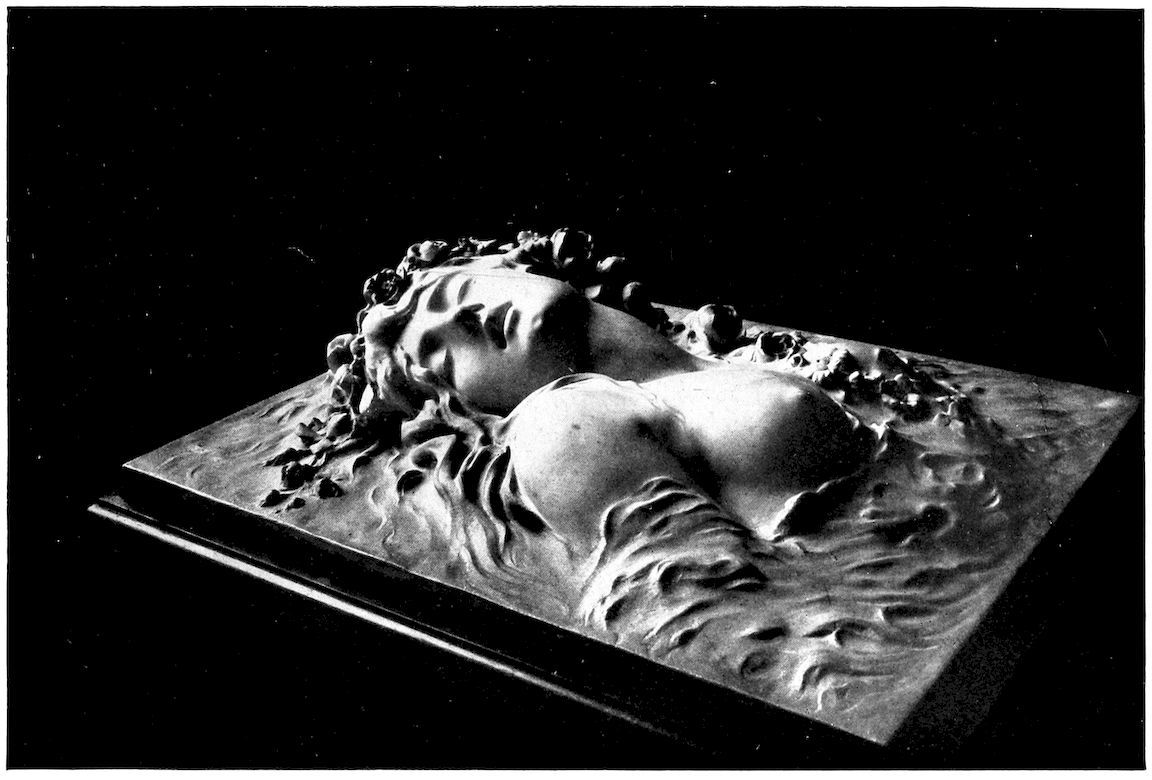

“OPHELIA”—SCULPTURE BY SARAH BERNHARDT.

I was greatly relieved on getting the news, and I played my last act with confidence. The great success of the evening, though, was Croizette’s, who was charming as the Marquise de Prie. My success, nevertheless, was assured in the performances which followed, and it became so marked that I was accused of paying for applause. I laughed heartily at this, and never even contradicted the report, as I have a horror of useless words.

I continued my débuts in “Junie de Britannicus,” having for hero Mounet-Sully, who played admirably. In this delicious rôle of Junie I obtained an immense and incredible success.

Then, in 1873 I played Chérubin in “Le Mariage de Figaro.” Croizette played Suzanne, and it was a real treat for the public to see the delicious creature play a part so full of gayety and charm. Chérubin was for me the opportunity of a fresh success.

In the month of March, 1873, Perrin took it into his head to stage “Dalila,” by Octave Feuillet. I was then taking the part of young girls, young princesses, or young boys. My slight frame, my pale face, my delicate aspect marked me out, for the time being, for the rôle of victim. When suddenly Perrin, finding that the victims attracted the pity of the public, and thinking that it was for this reason I pleased them, made the most ridiculous change in the distribution of the parts; he gave me the rôle of Dalila, the swarthy, wicked, and ferocious princess, and to Sophie Croizette he gave the rôle of the fair young dying girl.

The piece, under this strange distribution, was turned upside down. I forced my nature in order to appear the haughty and voluptuous siren; I stuffed my bodice with wadding, and the hips under my skirt with horsehair; but I kept my small, thin, sorrowful face. Croizette was obliged to repress the advantages of her bust by bands which oppressed and suffocated her, but she kept her pretty plump face with its dimples.

I was obliged to put on a strong voice, she to soften hers. In fact, it was absurd, and the piece was only a partial success.

After that I created “L’Absent,” a pretty piece in verse by Eugène Manuel, “Chez l’Avocat,” a very amusing thing in verse, by Paul Ferrier, where Coquelin and I quarreled beautifully. Then, August 22d, I played with immense success the rôle of Andromaque. I shall never forget the first performance, in which Mounet-Sully obtained a delirious triumph. Oh, how fine he was, Mounet-Sully, in his rôle of Oreste! His entrance, his fury, his madness, and the plastic beauty of this marvelous artiste—how fine it was! How magnificent!

After Andromaque I played Aricie in “Phedre”; and that evening in this secondary rôle, it was I who obtained, in reality, the success of the evening.

I took such a position, in a very short time, at the Comédie, that some of the artistes began to feel uneasy, and the management shared the anxiety. M. Perrin, an extremely intelligent man, whom I have always remembered with great affection, was horribly authoritative. I was authoritative, also, so that there was always perpetual warfare between us. He wanted to impose his will on me, and I would not submit to it. He was always ready to laugh at my outbursts when they were against the others, but he was furious when they were directed against himself. As for me, I will own that to get Perrin in a fury was one of my delights. He stammered so when he tried to talk quickly, he who weighed every word on ordinary occasions; the expression of his eyes, which was generally wavering, grew irritated and deceitful, and his pale, distinguished-looking face became mottled with patches of color, like the dregs of wine. His fury made him take his hat off and put it on again fifteen times in as many minutes, and his extremely smooth hair stood on end with this mad gallop of his headgear. Although I had certainly arrived at the age of discretion, I delighted in my wicked mischievousness, which I always regretted after, but which I was always ready to recommence, and even now after all the days, weeks, months, and years that I have lived since then, it still gives me infinite pleasure to play a joke on anyone. All the same, life at the Comédie began to affect my nerves.

I wanted to play Camille in “On ne Badine pas avec l’Amour.” The rôle was given to Croizette. I wanted to play Célimène; that rôle was Croizette’s. Perrin was very partial to Croizette. He admired her, and as she was very ambitious, she was most thoughtful and docile, which charmed the authoritative old man. She always obtained everything she wanted, and as Sophie Croizette was frank and straightforward, she often said to me when I was grumbling: “Do as I do, be more yielding, you pass your time in rebelling; I appear to be doing everything that Perrin wants me to do, but in reality I make him do all I want him to. Try the same thing.” I accordingly screwed up my courage and went to see Perrin. He nearly always said to me when we met:

“Ah, how do you do, Mlle. Revolt? Are you calm to-day?”

“Yes, very calm,” I replied; “but be amiable and grant me what I am going to ask you.” I tried to be charming, and spoke in my prettiest way. He almost purred with satisfaction, and was witty (this was no effort to him, as he was naturally so), and we got on very well together for a quarter of an hour. I then made my petition:

“Let me play Camille in ‘On ne Badine pas avec l’Amour.’”

“That’s impossible, my dear child,” he replied; “Croizette is playing it.”

“Well, then, we’ll both play it, we’ll take it in turns.”

“But Mlle. Croizette wouldn’t like that.”

“I’ve spoken to her about it, and she would not mind.”

“You ought not to have spoken to her about it.”

“Why not?”

“Because the distribution of parts concerns the management and not the artistes.”

He didn’t purr any more, he only growled. As for me, I was in a fury, and a few minutes later, I went out of the room, banging the door after me. All this preyed on my mind, though, and I used to cry all night. I then decided to take a studio and devote myself to sculpture. As I was not able to use my intelligence and my energy in creating rôles at the theater, as I wished, I gave myself up to another art, and began working at sculpture with frantic enthusiasm. I soon made great progress, and started on an enormous composition: “After the Storm.” I was indifferent now to the theater. Every morning at eight my horse was brought round and I went for a ride, and at ten I was back in my studio, 11 Boulevard de Clichy. I was very delicate, and my health suffered from the double effort I was making. I used to vomit blood in the most alarming way, and for hours together I was unconscious. I never went to the Comédie, except when obliged to by my duties there. My friends were seriously concerned about me, and Perrin was told what was going on. Finally, urged on by the Press and the Department of Fine Arts, he decided to give me a rôle to create in Octave Feuillet’s play “Le Sphinx.”

The principal rôle was for Croizette, but on hearing it read, I thought the part destined for me charming, and I resolved that it should also be the principal rôle. There would have to be two principal ones, that was all. The rehearsals went along very smoothly at the start, but it soon became evident that my rôle was more important than had been imagined, and friction soon began.

Croizette, herself, got nervous; Perrin was annoyed, and all this by-play had the effect of calming me. Octave Feuillet, a shrewd, charming man, extremely well bred and slightly ironical, thoroughly enjoyed the skirmishes that took place. War was doomed to break out, however, and the first hostilities came from Sophie Croizette.

I always wore in my bodice three or four roses which were apt to open under the influence of the warmth, and some of the petals naturally fell. One day, Sophie Croizette slipped down full length on the stage, and as she was tall and not slim, she fell rather indecently, and got up again ungracefully. The stifled laughter of some of the subordinate persons present stung her to the quick, and turning to me, she said: “It’s your fault, your roses fall and make everyone slip.” I began to laugh.

“Three petals of my roses have fallen,” I replied, “and there they all three are by the armchair on the prompt side, and you fell on the O. P. side. It isn’t my fault, therefore; it is just your own awkwardness.” The discussion continued and was rather heated on both sides. Two clans were formed, the “Croizettists,” and the “Bernhardtists,” war was declared, not between Sophie and me, but between our respective admirers and detractors. The rumor of these little quarrels spread in the world outside the theater and the public, too, began to form clans. Croizette had on her side all the bankers and all the people who were suffering from congestion. I had all the artists, the students, dying folks, and the failures. When once war was declared there was no drawing back from the strife. The first, the most fierce, and the definitive battle was fought over the moon.

We had begun the full-dress rehearsals. In the third act the scene was laid in a forest glade. In the middle of the stage was a huge rock upon which was Blanche (Croizette) kissing Savigny (Delaunay), who was supposed to be my husband. I (Berthe de Savigny) had to arrive by a little bridge over a stream of water. The glade was bathed in moonlight. Croizette had just played her part and her kiss had been greeted with a burst of applause by the house. This was rather daring in those days for the Comédie Française.

Suddenly a fresh burst of applause was heard. Amazement could be read on some faces, and Perrin stood up terrified. I was crossing the bridge, my pale face ravaged with grief, and the sortie de bal which was intended to cover my shoulders was dragging along, just held by my limp fingers; my arms were hanging down as though despair had taken the use out of them. I was bathed in the white light of the moon and the effect, it seems, was striking and deeply impressive. A nasal, aggressive voice cried out: “One moon effect is enough. Turn it off for Mlle. Bernhardt.”

I sprang forward to the front of the stage. “Excuse me, M. Perrin,” I exclaimed, “you had no right to take my moon away. The manuscript reads: ‘Berthe advances, pale, convulsed with emotion, the rays of the moon falling on her’... I am pale and I am convulsed ... I must have my moon!...”

“It is impossible,” roared Perrin. “Mlle. Croizette’s ‘You love me, then!’ and her kiss must have this moonlight. She is playing the Sphinx, that is the chief part in the play and we must leave her the principal effect....”

“Very well, then, give Croizette a brilliant moon, and give me a less brilliant one. I don’t mind that, but I must have my moon.” All the artistes and all the employés of the theater put their heads in at all the doorways and openings both on the stage and in the house itself. The “Croizettists” and the “Bernhardtists” began to comment on the discussion.

Octave Feuillet was appealed to, and got up in his turn.

“I grant that Mlle. Croizette is very beautiful in her moon effect. Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt is ideal, too, with her ray of moonlight. I want the moon, therefore, for both of them.”

Perrin could not control his anger. There was a discussion between the author and the director, followed by others between the artistes, and between the doorkeeper and the journalists who were questioning him. The rehearsal was interrupted; I declared that I would not play the part if I did not have my moon. For the next two days I received no notice of another rehearsal but through Croizette I heard that they were trying my rôle of Berthe privately. They had given it to a young woman whom we had nicknamed “the Crocodile,” because she followed all the rehearsals just as that animal follows boats—she was always hoping to snatch up some rôle that might happen to be thrown overboard. Octave Feuillet refused to accept the change of artistes and he came himself to fetch me, accompanied by Delaunay, who had negotiated matters.

“It’s all settled,” he said, kissing my hands, “there will be a moon for both of you.”

The first night was a triumph for both Croizette and for me. The party strife between the two clans waxed warmer and warmer, and this added to our success and amused us both immensely, for Croizette was always a delightful friend and a loyal comrade. She worked for her own ends, but never against anyone else.

After the “Sphinx” I played a pretty piece in one act by a young pupil of the Polytechnical School, Louis Denayrouse—“La Belle Paule.” This author has now become a renowned scientific man and has renounced his poetry.

I had begged Perrin to give me a month’s holiday, but he refused energetically, and compelled me to take part in the rehearsal of “Zaïre,” during the trying months of June and July, and in spite of my reluctance, announced the first performance for the 6th of August. That year it was fearfully hot in Paris. I believe that Perrin, who could not tame me alive, had, without really any bad intention, but by pure autocracy, the desire to tame me dead. Doctor Parrot went to see him and told him that my state of weakness was such that it would be positively dangerous for me to act during the trying heat. Perrin would hear nothing of it. Then, furious at the obstinacy of this intellectual bourgeois, I swore I would play on to the death.

Often, when I was a child, I wished to kill myself in order to vex others. I remember once having swallowed the contents of a large ink pot after being compelled by mamma to swallow a “panade”[2] because she imagined that panades were good for the health. Our nurse had told her my dislike to this form of nourishment, adding that every morning I emptied the panade into the slop pail. I had, of course, a very bad stomach ache, and screamed out in pain. I cried to mamma: “It is you who have killed me”—and my poor mother wept. She never knew the truth, but they never again made me swallow anything against my will.

Well, after so many years had gone over my head, I experienced the same bitter and childish sentiment. “I don’t care,” I said, “I shall certainly fall senseless, vomiting blood, and perhaps I shall die! And it will serve Perrin right. He will be furious!” Yes, that is what I thought. I am, at times, very foolish. Why? I don’t know how to explain it, but I admit it.

The 6th of August, therefore, I played, in tropical heat, the part of Zaïre. The entire audience was bathed in perspiration. I saw the spectators through a mist. The piece, badly staged as regards scenery, but very well presented as regards costumes, was particularly well played by Mounet-Sully, Orosmane, Laroche, Nerestan, and myself—Zaïre—and obtained an immense success.

I was determined to faint, determined to vomit blood, determined to die, in order to enrage Perrin. I gave myself entirely up to it. I had sobbed, I had loved, I had suffered, and I had been stabbed by the poignard of Orosmane, uttering a true cry of suffering, for I had felt the steel penetrate my breast; then falling panting, dying, on the Oriental divan, I had meant to die in reality, and dared scarcely move my arms, convinced as I was that I was in my death agony and somewhat afraid, I must admit, at having succeeded in playing such a nasty trick on Perrin. But my surprise was great when the curtain fell at the close of the piece, and I got up quickly to answer to the call and salute the public without languor, without fainting, ready to recommence the piece.

And I marked this performance with a little white stone—for that day I learned that my vital force was at the service of my intellect. I had desired to follow the impulse of my brain, whose conceptions seemed to me to be too forceful for my physical strength to carry out and I found myself, having given out all of which I was capable—and more—in perfect equilibrium.

Then I saw the possibility of the longed-for future.

I had fancied, and up to this performance of Zaïre I had always heard, and read in the papers that my voice was pretty, but weak; that my gestures were gracious, but vague; that my supple movements lacked authority, and that my glance lost in heavenward contemplation, could not tame the lion (the public). I thought then of all that. I had received proof that I could count on my physical strength, for I had commenced the performance of Zaïre in such a state of weakness that it was easy to predict that I should not finish the first act without fainting.

On the other hand, although the rôle was easy, it required two or three shrieks which might have provoked the vomiting of blood which frequently troubled me at that time. That evening, therefore, I acquired the certainty that I could count on the strength of my vocal cords, for I had uttered my shrieks with real rage and suffering, hoping to break something in my wild desire to be revenged on Perrin.

Thus, this little comedy turned to my profit. Not being able to die at will, I faced about and resolved to be strong, vivacious, and active, to the great annoyance of some of my contemporaries, who had put up with me only because they thought I would soon die, but who began to hate me as soon as they acquired the conviction that I should perhaps live for a long time. I will give only one example, related by Alexandre Dumas, fils, who was present at the death of his intimate friend, Charles Narrey, and heard his dying words: “I am content to die because I shall hear no more of Sarah Bernhardt and of the great Français” (Ferdinand de Lesseps).