CHAPTER XX

A BALLOON ASCENSION

As I had a continual thirst for what was new, I now tried my hand at painting. I knew how to draw a little and had a well-developed sense of color. I first did two or three small pictures—then I undertook the portrait of my dear Guérard. Alfred Stevens thought it was vigorously done, and Georges Clairin encouraged me to continue with painting. Then I launched out courageously, boldly. I began a picture which was nearly two meters in size: “The Young Girl and Death.”

Then there was a cry of indignation against me.

Why did I want to do anything else but act, since that was my career?

Why did I always want to be before the public?

Perrin came to see me one day when I was very ill. He began to preach. “You are killing yourself, my dear child,” he said. “Why do you go in for sculpture, painting, etc.? Is it to prove that you can do it?”

“Oh, no, no,” I answered; “it is merely to create a necessity for staying here!”

“I don’t understand,” said Perrin, listening very attentively.

“This is how it is. I have a wild desire to travel, to see something else, to breathe another air, and to see skies that are higher than ours and trees that are bigger; something different, in short. I have therefore had to create for myself some tasks which will hold me to my chains. If I did not do this, I feel that my desire to see other things in the world would win the day and I should do something foolish.”

This conversation was destined to go against me some years later when the Comédie brought an action against me.

The Exhibition of 1878 put the finishing stroke to the state of exasperation that Perrin and some of the artistes of the theater were in with regard to me. They blamed me for everything, for my painting, my sculpture, and my health. I had a terrible scene with Perrin and it was the last one, for from that time forth we did not speak to each other again; a formal bow was the most that we exchanged afterwards.

The climax was reached over my balloon ascension. I adored and I still adore balloons. Every day I went up in M. Giffard’s captive balloon. This persistency had struck the savant and he asked a mutual friend to introduce him.

“Oh, M. Giffard,” I said, “how I should like to go up in a balloon that is not captive!”

“Well, mademoiselle, you shall do so if you like,” he replied very kindly.

“When?” I asked.

“Any day you like.”

I should have liked to start immediately, but as he pointed out he would have to fit the balloon up and it was a great responsibility for him to undertake. We therefore fixed upon the following Tuesday, just a week from then. I asked M. Giffard to say nothing about it, for if the newspapers should get hold of this piece of news, my terrified family would not allow me to go. M. Tissandier, who a little time after was doomed, poor fellow, to be killed in an aërial accident, promised to accompany me. Something happened, however, to prevent his going with me, and it was young Godard who the following week accompanied me in the Doña Sol—a beautiful orange-colored balloon specially prepared for my expedition. Prince Jerome Napoleon (Plon-Plon), who was with me when Giffard was introduced, insisted on going with us. But he was heavy and rather clumsy and I did not care much about his conversation, in spite of his marvelous wit, for he was spiteful and rather delighted when he could get a chance to attack the Emperor Napoleon III, whom I liked very much.

We started alone, Georges Clairin, Godard, and I. The rumor of our journey had nevertheless spread, but too late for the Press to get hold of it. I had been up in the air about five minutes when one of my friends, Count de M——, met Perrin on the Pont des Saints-Pères.

“I say,” he began, “look up in the sky! There is your star shooting away.”

Perrin looked up, and pointing to the balloon which was rising he asked: “Who is in that?”

“Sarah Bernhardt,” replied my friend. Perrin, it appears, turned purple, and clenching his teeth, he murmured: “That’s another of her freaks, but she will pay for this.”

He hurried away without even saying good-by to my young friend, who stood there stupefied at this unreasonable burst of anger.

And if he had suspected my infinite joy at thus traveling through the air, Perrin would have suffered still more.

Ah, our departure! It was half past five. I shook hands with a few friends. My family, whom I had kept in the most profound ignorance, was not there. I felt my heart tighten somewhat when after the words “Loose all” I found myself in one instant fifty yards above the earth. I still heard a few cries: “Attention! Come back! Don’t let her be killed!” And then nothing more.... Nothing.... There was the sky above and the earth beneath.... Then, suddenly, I was in the clouds. I had left a misty Paris. I now breathed under a blue sky and saw a radiant sun. Around us were opaque mountains of clouds with irradiated edges. Our balloon plunged into a milky vapor all warm with the sun. It was splendid! It was stupefying! Not a sound, not a breath! But the balloon was scarcely moving at all. It was only toward six o’clock that the currents of air caught us and we took our flight toward the East. We were at an altitude of about 1,700 yards. The spectacle became fairylike. Large fleecy clouds were spread below us. Large orange curtains fringed with violet came down from the sun to lose themselves in our cloudy carpet.

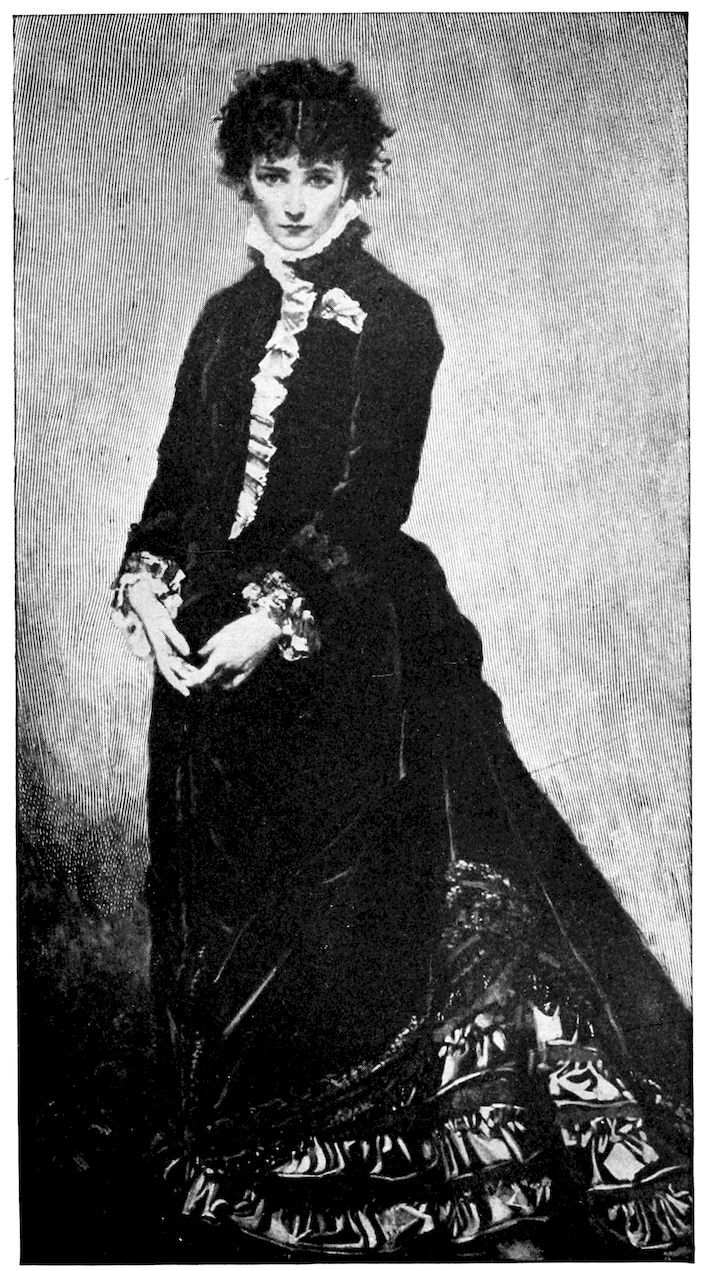

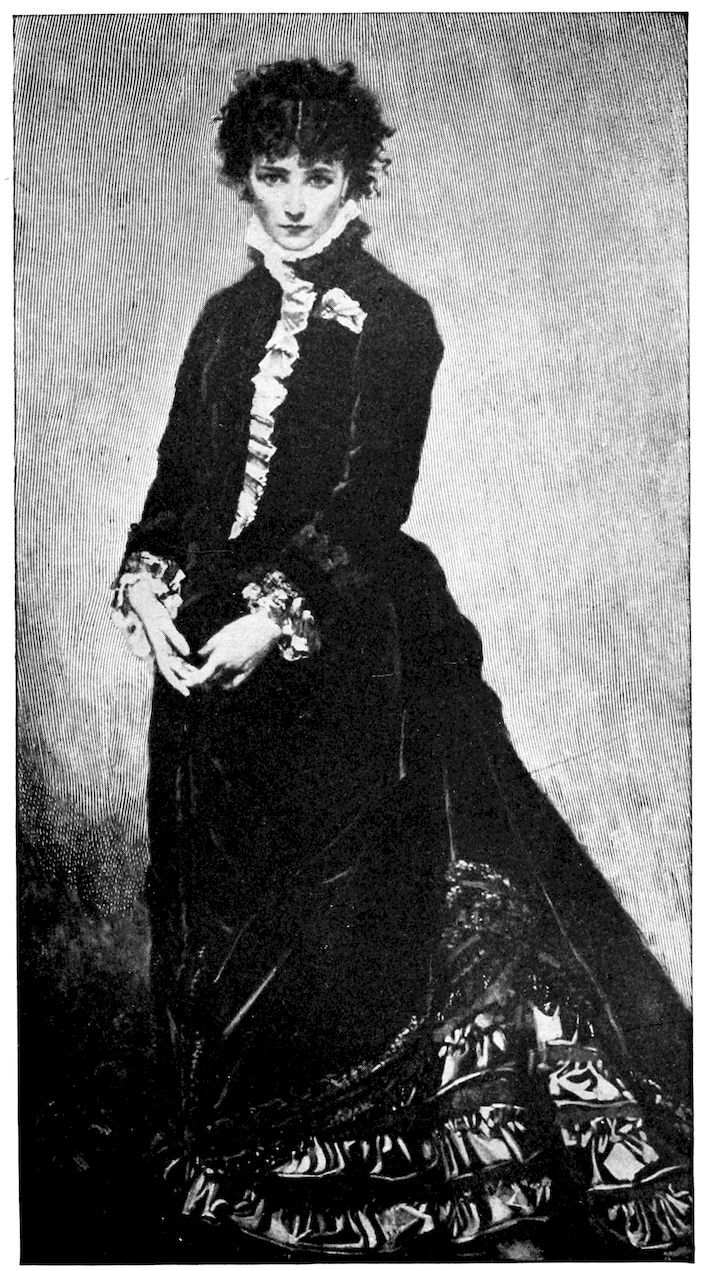

SARAH BERNHARDT, PORTRAIT BY PARROTT, 1875, IN THE COMÉDIE FRANÇAISE, PARIS.

At twenty minutes to seven we were about 2,500 yards above the earth, and cold and hunger commenced to make themselves felt.

The dinner was copious—we had foie gras—fresh bread and oranges. The cork of our champagne bottle flew up into the clouds with a pretty, soft noise. We raised our glasses in honor of M. Giffard.

We had talked a great deal. Night began to put on her heavy dark mantle. It became very cold. We were then at 2,600 meters and I had a singing in my ears. My nose began to bleed. I felt very uncomfortable and began to feel drowsy without being able to prevent it. Georges Clairin got anxious and young Godard cried out loudly—to wake me up, no doubt—“Alloa! Alloa! we shall have to go down. Let us throw out the guide rope!” This cry woke me up properly. I wanted to know what was the guide rope. I got up feeling rather stupefied, and in order to rouse me Godard put the guide rope into my hands. It was a strong rope, about 130 meters long, to which were attached at certain distances little iron hooks. Clairin and I let out the rope, laughing, while Godard bending over the side of the car was looking through a field glass.

“Stop!” cried he suddenly. “There are a lot of trees!”

In fact, we were over the wood of Ferrières. But just in front of us there was a little open ground suitable for our descent.

“There is no doubt about it,” cried Godard, “if we miss this plain we shall come down in the black night in the wood of Ferrières, and that would be very dangerous!” Then, turning to me, “Will you,” he said, “open the valve?”

I immediately did so, and the gas came out of its prison, whistling a mocking air. The valve was shut by order of the aëronaut, and we descended rapidly. Suddenly the stillness of the night was broken by the sound of a horn. I trembled. It was Louis Godard, who had pulled out of his pocket, which was a veritable storehouse, a sort of horn, on which he blew with violence. A loud whistle answered our call, and 500 meters below us we saw a man who was shouting his hardest to make us hear. As we were very close to a little station we easily guessed that this man was the station master.

“Where are we?” cried Louis Godard, with his horn.

“At—in—in—ille,” answered the station master. It was impossible to understand.

“Where are we?” thundered Georges Clairin in his most formidable tones.

“At—in—in—ille,” shouted the station master with his hand curved round his mouth.

“Where are we?” called I in my most crystalline accents.

“At—in—in—ille,” answered the station master—and his porters.

It was impossible to find out anything. We had to lower the balloon. At first we descended rather too quickly and the wind blew us toward the wood. We had to mount again. But ten minutes later we opened the valve again and made a fresh descent. The balloon was then to the right of the station, and far from the amiable station master.

“Throw out the anchor!” cried in a commanding tone young Godard. And helped by Georges Clairin he threw out into space another rope, to the end of which was fastened a formidable anchor. The rope was 80 meters long.

Down below us a crowd of children of all ages had been running ever since we stopped above the station. When we got to about 300 yards from the earth, Godard called out to them: “Where are we?”

“At Vachère!”

None of us knew Vachère. But we descended nevertheless.

“Alloa! You down below there—take hold of the guide rope,” cried the aëronaut, “and mind you don’t pull too hard!” Five vigorous men seized hold of the rope. We were 130 meters from the ground, and the spectacle became interesting. The night began to blot out everything. I raised my head to see the sky, but I remained with my mouth open with astonishment. I saw only the lower end of our balloon, which was overhanging its base all loose and baggy. It was very ugly.

We anchored gently, without the little dragging which I hoped would happen, and without the little drama which I had half expected.

It began to rain in torrents as we left the balloon.

The young owner of a neighboring château ran up, like the peasants, to see what was going on. He offered me his umbrella.

“Oh, I am so thin I cannot get wet! I pass between the drops.”

The word was repeated, and has become almost a proverb.

“What time is there a train?” asked Godard.

“Oh, you have plenty of time!” answered an oily and heavy voice. “You cannot leave before ten o’clock, as the station is a long way from here, and in such weather it will take the young lady two hours to walk there.”

I was confounded, and looked for the young gentleman with the umbrella, which I could have used as a walking stick, as neither Clairin nor Godard had one. But just as I was accusing him of going away and leaving us, he jumped lightly out of a vehicle which I had not heard drive up.

“There!” said he. “There is a carriage for you and these gentlemen, and another for the body of the balloon.”

“Ma foi! You have saved us,” said Clairin, clasping his hand, “for it appears the roads are in a very bad state.”

“Oh,” said the young man, “it would be impossible for the feet of Parisians to walk even half the distance.”

Then he bowed and wished us a pleasant journey.

Rather more than an hour later we arrived at the station of Emerainville. The station master, learning who we were, received us in a very friendly manner. He made his apologies for not having heard when we called out. He had a frugal meal of bread, cheese, and cider set before us. I have always detested cheese, and would never eat it—there is nothing poetical about it—but I was dying with hunger.

“Taste it, taste it,” said Georges Clairin.

I bit a morsel off and found it excellent.

We got back very late, in the middle of the night, and I found my household in an extreme state of anxiety. Our friends, who had come to hear news of us, had stayed. There was quite a crowd. I was somewhat annoyed at this, as I was half dead with fatigue.

I sent everybody away rather sharply and went up to my room. As my maid was helping me to undress she told me that some one had come for me from the Comédie Française several times.

“Oh, mon Dieu!” I cried anxiously. “Could the piece have been changed?”

“No, I don’t think so,” said the maid. “But it appears that M. Perrin is furious, and that they are all against you. There is the note which was left for you.”

I opened the letter. I was requested to appear before the Administration the following day at two o’clock.

On my arrival at Perrin’s at the time appointed, I was received with an exaggerated politeness which had an undercurrent of severity.

Then commenced a series of onslaughts on my fits of ill temper, my caprices, my eccentricities; and he finished his speech by saying that I had incurred a fine of £40 for traveling without the consent of the manager.

I burst out laughing: “The case of a balloon has not been foreseen,” I said, “and I can promise you I shall pay no fine. Outside the theater I do as I please, and that is no business of yours, my dear M. Perrin, so long as I am not doing anything that would injure my theatrical work! And, besides—you bore me to death!—I will resign!—Be happy!”

I left him ashamed and anxious.

The next day I sent in my written resignation to M. Perrin, and shortly afterwards I was sent for by M. Turquet, Minister of Fine Arts. I refused to go, and they sent a mutual friend, who stated that M. Perrin had gone further than he had any right, that the fine was remitted, and that I must take back my resignation. So I did.

But the situation was strained. My fame had become annoying for my enemies, and a little trying, I confess, for my friends. But at this time all this stir and noise amused me vastly. I did nothing to attract attention; but my fantastic tastes, my paleness and thinness, my particular way of dressing, my scorn of fashion, my general freedom in all respects, made me a being set apart. I did not recognize this fact.

I did not read—I never read—the newspapers. So I did not know what was said about me, either favorable or unfavorable. Surrounded by a court of adorers of both sexes, I lived in a sunny dream. All the royal personages and the notabilities who were the guests of France during the Exhibition of 1878 came to see me. This was a constant source of pleasure to me.

The Comédie was the first theatrical stage of all these illustrious visitors, and Croizette and I played nearly every evening. While I was playing Amphytrion I fell seriously ill, and was sent to the South.

I remained there two months. I lived at Mentone, but I made Cap Martin my headquarters. I had a tent put up on the spot that the Empress Eugénie afterwards selected to build her villa. I did not want to see anybody, and I thought that by living in a tent, so far from the town, I should not be troubled with visitors. This was a mistake. One day when I was having lunch with my little boy, I heard the bells of two horses which had come with a carriage. The road overhung my tent, which was half hidden by the bushes. Suddenly a voice which I knew, but could not recognize, cried in the emphatic tone of a herald:

“Does Sarah Bernhardt, Associate of the Comédie Française, live here?”

We did not move. The question was asked again. Again the answer was silence. But we heard the sound of breaking branches, the bushes were pushed apart, and at two yards from the tent the teasing voice recommenced.

We were discovered. Somewhat annoyed I came out. I saw before me a man with a large tussore cloak on, a field glass strapped on his shoulders, a gray bowler hat, and a red, happy face with a little pointed beard. I glanced at this commonplace-looking individual with anything but favor. He lifted his hat:

“Mme. Sarah Bernhardt is here?”

“What do you want with me, sir?”

“Here is my card, madame.”

I read: “Gambard, Nice, Villa des Palmiers.” I looked at him with astonishment, and he was still more astonished to see that his name did not produce any impression on me. He had a foreign accent.

“Well, you see, madame, I come to ask you to sell us your group, ‘After the Tempest.’”

I began to laugh.

“Ma foi, monsieur, I am treating for that with the firm of Susse, and they offer me 6000 francs. If you will give ten, you may have it.”

“Quite right,” he said. “Here are 10,000 francs. Have you pen and ink?”

“No.”

“Ah,” said he, “allow me.” And he produced a little case in which there was pen and ink.

I made out the receipt, and gave him an order to go and take the group at Paris, in my studio. He went away, and I heard the bells of the horses ringing and then dying away in the distance. After this I was often invited to the house of this original person, who was one of the negro kings of Nice.

Shortly after I came back to Paris. At the theater they were preparing for the benefit night of Bressant, who was about to leave the stage. It was agreed that Mounet-Sully and I should play an act from “Othello,” by Jean Aicard. The theater was well filled, and the audience in a good humor. After the song of Saule, I was in bed as Desdemona, when suddenly I heard the public laugh, softly at first, and then irrepressibly. Othello had just come in, in the darkness, in his shirt or very little more, with a lantern in his hand, and gone to a door hidden in some drapery. The public, that impersonal unity, has no hesitation in taking part in a manifestation of unseemly mirth that each member of the audience, taken as a separate individual, would be ashamed to admit. But the ridicule thrown on this act by the exaggerated pantomime of the actor prevented the play being staged again, and it was only twenty years later that “Othello,” as an entire play, was produced at the Théâtre Français. I was then no longer there.

After having played Berenice, in “Mithridate,” successfully, I took up again my rôle of the Queen in “Ruy Blas.” The play was as successful at the Théâtre Français as at the Odéon, and the public was, if anything, still more favorable to me. Mounet-Sully played Ruy Blas. He took the part admirably, and was infinitely better than Lafontaine, who played it at the Odéon. Frédéric Febvre, very well dressed, represented his part very well, but he was not so good as Geffroy, who was the most distinguished and the most frightful Don Salluste that could be imagined.

My relations with Perrin were more and more strained.

He was pleased that I was successful, for the sake of the theater; he was happy at the magnificent receipts of “Ruy Blas”; but he would have much preferred that it had been another than I who received all the applause. My independence, my horror of submission, even in appearance, annoyed him vastly.

One day my servant came to tell me that an elderly Englishman was asking to see me so insistently that he thought it better to come and tell me, though I had given orders I was not to be disturbed.

“Send him away and let me work in peace.”

I was just commencing a picture which interested me very much. It represented a little girl on Palm Sunday, carrying branches of palm. The little model who posed for me was a lovely Italian of eight years old. Suddenly she said to me:

“He’s quarreling—that Englishman!”

As a matter of fact, in the anteroom there was a noise of voices rising higher and higher. Irritated, I rushed out, my palette in my hand, resolved to make the intruder flee. But just at the moment when I opened the door of my studio, a tall man came so close to me that I drew back, and he came into my hall. His eyes were clear and piercing, his hair silvery white, and his beard carefully trimmed. He made his excuses very politely, admired my paintings, my sculpture, my hall—and this while I was in complete ignorance of his name. When at the end of ten minutes I begged him to sit down and tell me to what I owed the pleasure of his visit, he replied in a stilted voice with a strong accent:

“I am Mr. Jarrett, the impresario. I can make your fortune. Will you come to America?”

“Never!” I exclaimed firmly. “Never!”

“Oh, well, don’t get angry! Here is my address—don’t lose it.” Then, at the moment he took leave, he said:

“Ah! you are going to London with the Comédie Française. Would you like to earn a lot of money in London?”

“Yes. How?”

“By playing in drawing-rooms. I can make you a small fortune.”

“Oh, I would be pleased to do that—that is, if I go to London, for I have not yet decided.”

“Then will you sign a little contract to which we will add an additional clause?”

And I signed a contract with this man, who inspired me with confidence at first sight—a confidence which he never betrayed.

The Committee and M. Perrin had made an agreement with John Hollingshead, director of the Gaiety Theater, in London. Nobody had been consulted and I thought that was a little too free and easy. So when they told me about this agreement, I said nothing. Perrin rather anxiously took me aside:

“What are you turning over in your mind?”

“I am turning over this: that I will not go to London in a situation inferior to anybody. For the entire term of my contract I intend to be Associate à part entière (with full benefit).”

This intention excited the Committee highly. And the next day Perrin told me that my proposal was rejected.

“Well, I shall not go to London. That is all! Nothing in my contract obliges me to go.”

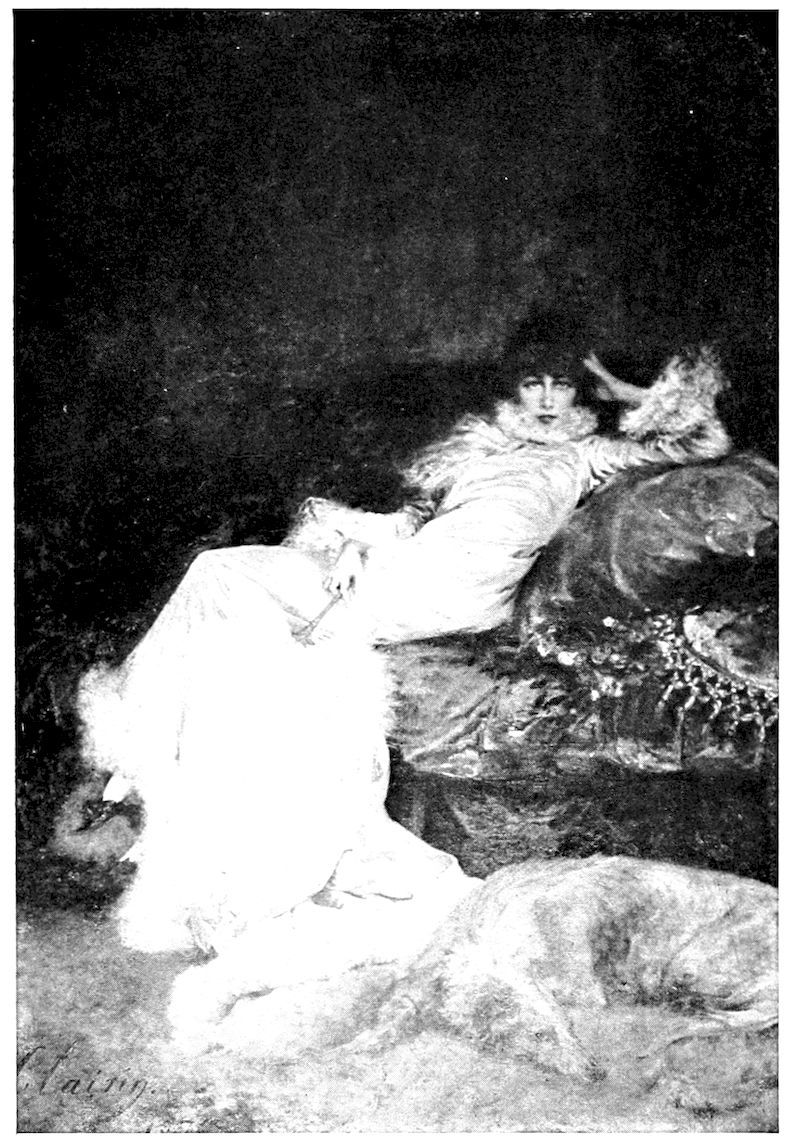

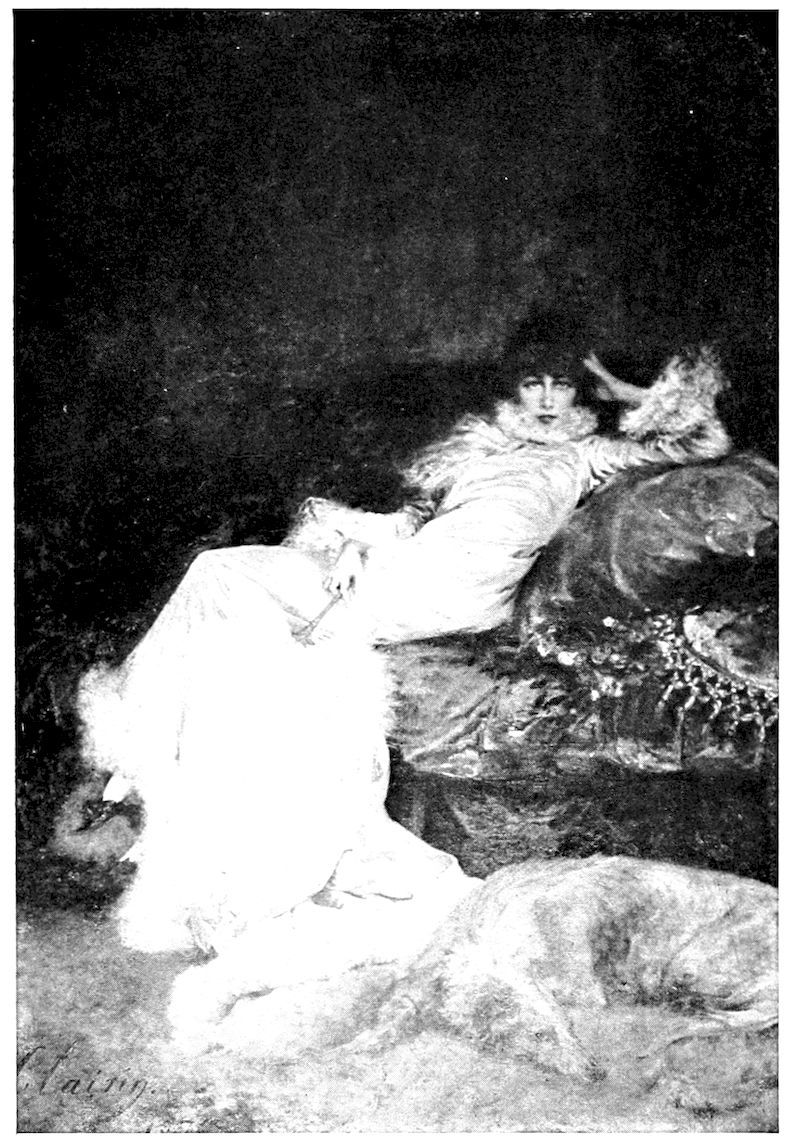

SARAH BERNHARDT, PORTRAIT BY CLAIRIN.

The Committee met again, and Got cried out: “Well, let her stay away! She is a regular nuisance!”

It was therefore decided that I should not go to London. But Hollingshead and Mayer, his partner, did not see it in this light, and they declared that the contract would not be binding if either Croizette, Mounet-Sully, or I did not go.

The agents, who had bought two hundred thousand francs’ worth of tickets beforehand, also refused to regard the affair as binding on them if we did not go. Mayer came to see me in profound despair and told me all about it.

“We shall have to break our contract with the Comédie if you don’t come,” he said, “for the business cannot go through.”

Frightened at the consequences of my bad temper, I ran to see Perrin, and told him that after the consultation I had just had with Mayer, I understood the involuntary injury I should be causing to the Théâtre Français and to my comrades, and I told him I was ready to go under any conditions.

The Committee was holding a meeting. Perrin asked me to wait and shortly after he returned: Croizette and I had been appointed Associates with full benefit (Sociétaires à part entière), not only for London, but for always.

Everybody had done his duty. Perrin, very much touched, took both my hands and drew me to him:

“Oh, the good and untamable little creature!”

We embraced and peace was again concluded between us. But it could not last long, for five days after this reconciliation, about nine o’clock in the evening, M. Perrin was announced at my house. I had company for dinner. Nevertheless, I was about to receive him in the hall. He held out to me a paper.

“Read that,” said he.

And I read in an English newspaper, the Times, this paragraph:

“Drawing-room Comedies of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt, under the management of Sir Benedict:

“The répertoire of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt is composed of comedies, proverbs, one-act plays and monologues, written especially for her and one or two artistes of the Comédie Française. These comedies are played without accessories or scenery, and can be adapted both in London and Paris to the matinées and soirées of the best society. For all details and conditions please communicate with Mr. Jarrett (Secretary of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt) at His Majesty’s Theatre.”

As I was reading the last lines it dawned on me that Jarrett, learning that I was certainly coming to London, had begun to advertise me. I frankly explained this to Perrin.

“What objection is there,” I said, “to my making use of my evenings to earn money, as the thing has been offered me?”

“That has nothing to do with me—it is the business of the Committee.”

“That is too much!” I cried, and calling for my secretary I said: “Give me Delaunay’s letter that I gave you yesterday.”

He brought it out of one of his numerous pockets and gave it to Perrin to read:

Would you care to come and play “La Nuit d’Octobre” at Lady Dudley’s on Thursday, June 5th? They will give us each 5,000 francs. Kind regards,

DELAUNAY.

“Let me have this letter,” said the manager, visibly annoyed.

“No, I will not. But you may tell Delaunay that I have told you of his offer.”

For the next two or three days nothing was talked of in Paris but the scandalous announcement of the Times. The French were then almost entirely ignorant of the habits and customs of the English. At last all this talk annoyed me, and I begged Perrin to try and stop it, and the following day there appeared in the National of the 29th of May:

“Much Ado About Nothing. In friendly discussion it has been decided that outside the rehearsals and the performances of the Comédie Française, each artist is free to employ his time as he sees fit. There is therefore absolutely no truth at all in the pretended quarrel between the Comédie Française and Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt. This artiste has only acted strictly within her rights, which nobody attempts to limit, and all our artistes intend to benefit in the same manner. The manager of the Comédie Française asks only that the artistes who form this ‘corps’ do not give performances in a body.”

This article came from the Comédie, and the members of the Committee had taken advantage of it to advertise a little for themselves, announcing that they also were ready to play in drawing-rooms, for the article was sent to Mayer with a request that it should appear in the English papers. It was Mayer himself who told me this.

All disputes being at an end, we commenced our preparations for departure.