CHAPTER XIX

BUSY DAYS

One day Alexandre Dumas, fils, was announced. He came to bring me the good news that he had finished his play for the Comédie Française: “L’Etrangère,” and that my rôle, the Duchess de Septmonts, had come out very well. “You can,” he said to me, “make a fine success out of it.” I expressed my gratitude to him.

A month after this visit we were convoked to the Comédie for the reading of this piece.

The reading was a great success, and I was delighted with my rôle: Catherine de Septmonts. I also liked the rôle of Croizette: Mistress Clarkson. Got gave us each our parts, and thinking that he had made a mistake I passed on to Croizette the rôle of l’Etrangère, which he had just given me, saying to her: “Here, Got has made a mistake—here is your rôle.”

“But he is not making any mistake, it is I who am to play the Duchess de Septmonts.”

I burst out into irrepressible laughter, which surprised everybody present, and when Perrin, annoyed, asked me why I was laughing like that, I exclaimed:

“At all of you—you, Dumas, Got, Croizette—and all of you who are in the plot, and who are all a little afraid of the result of your cowardice. Well, you need not alarm yourselves. I was delighted to play the Duchesse de Septmonts, but I shall be ten times more delighted to play the Stranger. And this time, my dear Sophie, I make no account of you; you are not worth considering, for you have played me a little trick which was quite unworthy of our friendship!”

The rehearsals were strained on all sides. Perrin, who was a warm partisan of Croizette, bewailed the want of suppleness of her talent, so much so that one day Croizette, out of all patience, burst out:

“Well, monsieur, you should have left the rôle to Sarah, she would have taken the part in the love scenes as you wish; I cannot do any better. You irritate me too much, I have had enough of it!” And she ran off, sobbing, into the little guignol, where she had an attack of hysteria. I followed her and consoled her as well as I could. And in the midst of her tears she kissed me, murmuring: “It is true, it is they who instigated me to do this nasty trick, and now they are bothering me.” Croizette spoke broadly—very broadly—and sometimes she had quite a provincial accent.

Then we made up our quarrel entirely.

A week before the first performance I received an anonymous letter informing me that Perrin was trying his very best to get Dumas to change the name of the piece. He wished—it goes without saying—to have the piece called “La Duchesse de Septmonts.” I rushed off to the theater to find Perrin at once. At the door I met Coquelin, who was taking the part of the Duc de Septmonts, which he did marvelously well. I showed him the letter. He shrugged his shoulders. “It is infamous! But why do you take any notice of an anonymous letter? It is not worthy of you!” We were talking at the foot of the staircase when the manager arrived.

“Here, show the letter to Perrin.” And he took it from my hands in order to show it to him. Perrin reddened slightly.

“I know this writing,” he said. “It is some one from the theater who has written this letter.”

I snatched it back from him. “Then it is some one who is well informed, and what he says is perhaps true, is it not so? Tell me, I have the right to know.”

“I detest anonymous letters.” And he went up the stairs with a slight bow, without saying anything further.

“Ah, if it is true,” said Coquelin, “it is too much! Would you like me to go to see Dumas? I will find out at once.”

“No, thank you. But you have put an idea into my head.” And shaking hands with him I went off immediately to see Dumas, fils. He was just going out.

“Well, well! What is the matter? Your eyes are blazing!”

I went with him into the drawing-room and asked my question at once. He had kept his hat on and took it off to recover his self-possession. Before he could speak a word I got furiously angry—one of those rages which I sometimes have, and which are more like attacks of madness. With all that I felt of bitterness toward this man, toward Perrin, toward all this theatrical world who should have loved me and upheld me, and who betrayed me on every occasion—all that I had been accumulating of hot anger during the rehearsals, the cries of revolt against the perpetual injustice of these two men, Perrin and Dumas—I burst out with everything, in an avalanche of stinging words, which were both furious and sincere. I reminded him of his promise made in former days; of his visit to my hôtel in the Avenue de Villiers; of the cowardly and underhand manner in which he had written of me, at Perrin’s request, and on the wishes of the friends of Sophie.... I spoke vehemently, without allowing him to edge in a single word. And when, worn out, I was forced to stop, I murmured, out of breath with fatigue: “What—what—what have you to say for yourself?”

“My dear child,” he replied, much touched, “if I had examined my own conscience I should have said to myself all that you have just said to me so eloquently. But I can truly say, in order to excuse myself a little, that I really believed that you did not care at all about your theater; that you much preferred your sculpture, your painting, and your court. We have seldom talked together, and people led me to believe all that which I was perhaps too ready to believe. Your grief and anger have touched me deeply. I give you my word that the play shall keep its title of ‘L’Etrangère.’ And now, embrace me with a good grace, to show that you are no longer angry with me.”

I embraced him, and from that day we were good friends.

That evening I told the whole tale to Croizette, and I saw that she knew nothing about this wicked scheme. I was very pleased to know that.

The play was very successful. Coquelin, Febvre, and I carried off the laurels of the day.

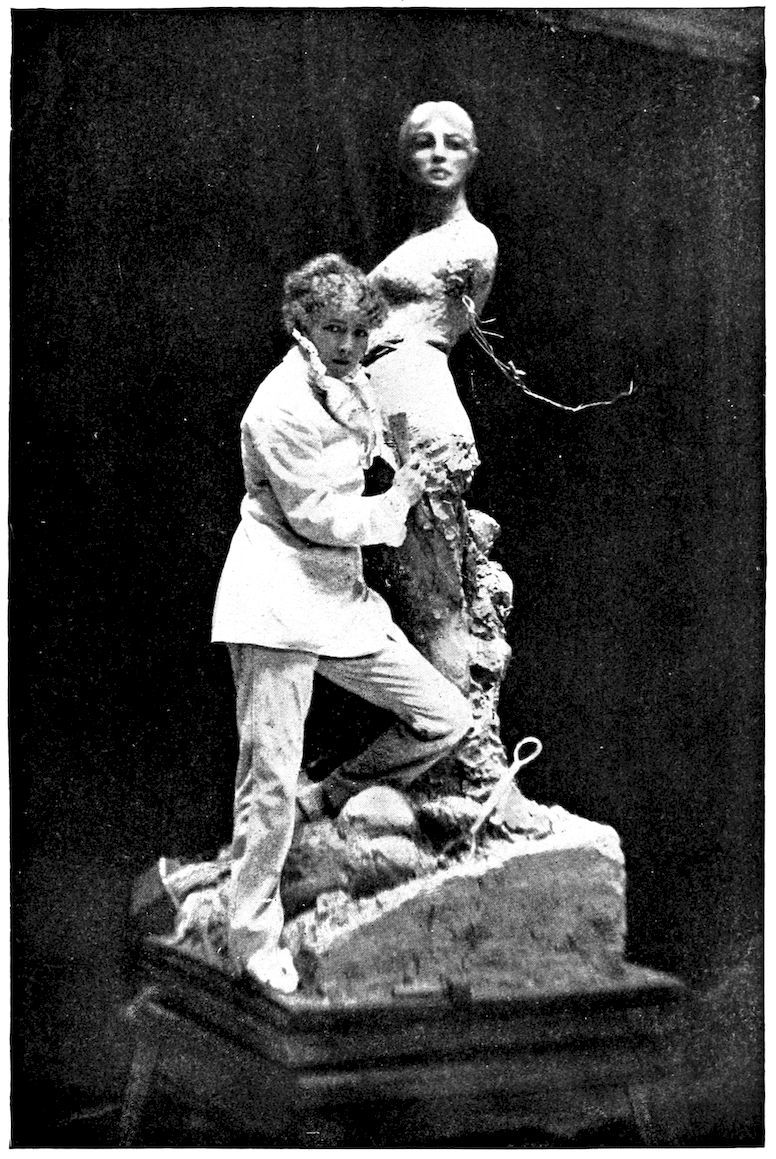

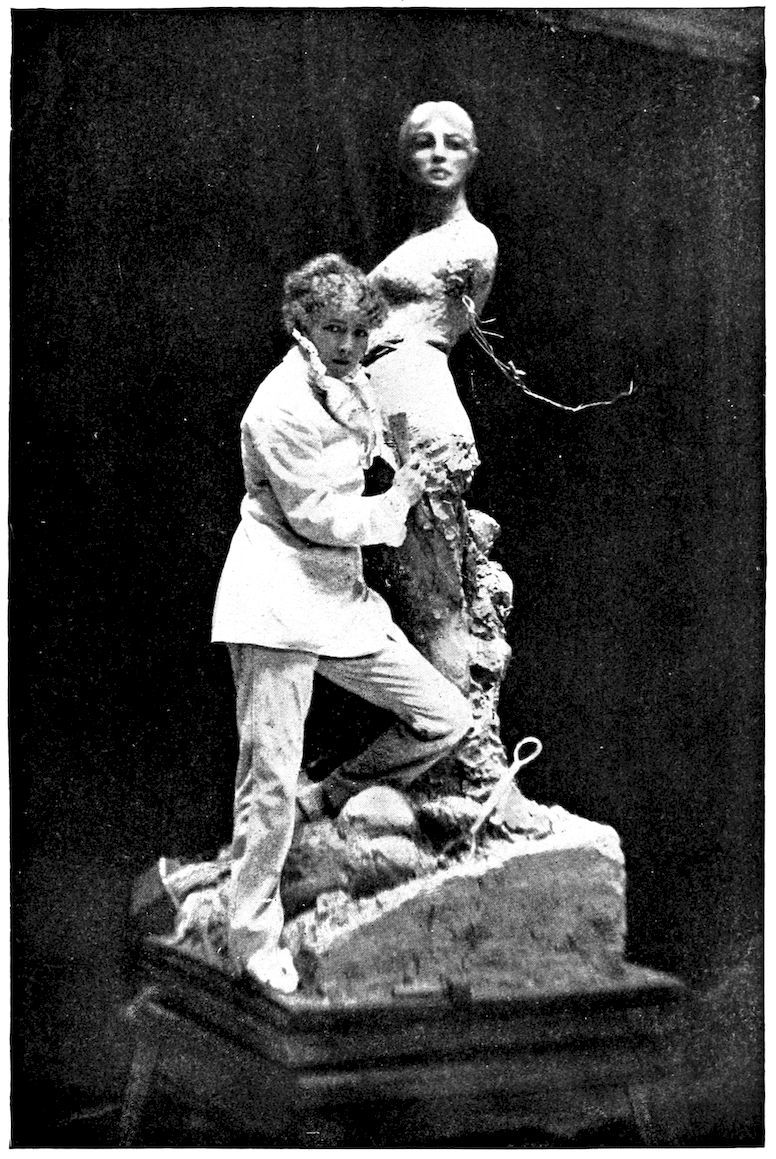

I had just commenced in my studio, in the Avenue de Clichy, a large group, the inspiration for which I had gathered from the sad history of an old woman whom I often saw at nightfall in the Baie des Trépassés. One day I went up to her wishing to speak to her, but I was so terrified by her aspect of madness that I rushed off at once, and the guardian told me her history. She was the mother of five sons—all sailors. Two had been killed by the Germans in 1870, and three had been drowned. She had brought up the little son of her youngest boy, always keeping him far from the sea and teaching him to hate the water. She had never left the little lad; but he became so sad that he was really ill, and he said he was dying because he wanted to see the sea. “Well, make haste and get well,” said the grandmother tenderly, “and we will go and visit the sea together.” Two days later the child was better, and the grandmother left the valley in the company of her little grandson to go and see the ocean, the grave of her three sons.

It was a November day. A low sky hung over the sea limiting the horizon. The child jumped with joy. He ran, gamboled, and sang for happiness when he saw all this living water. The grandmother sat on the sand and hid her tearful eyes in her two trembling hands; then, suddenly, struck by the silence, she looked up in terror. There, in front of her she saw a boat drifting, and in the boat her boy, her little lad of eight years old, who was laughing right merrily, paddling as well as he could with one oar that he could hardly hold, and crying out: “I am going to see what there is behind the mist and I will come back.”

He never came back. And the following day they found the poor old woman talking low to the waves which came and bathed her feet. She came every day to the water’s edge, throwing in the bread which kindly folk gave her and saying to the waves: “You must carry that to the little lad.”

This touching narrative had remained in my memory. I can still see the tall old woman with her brown cape and hood. I worked feverishly at the group. It seemed to me now that I was destined to be a sculptor and I began to despise my theater. I went there only when I was compelled by my duties and I left it as soon as possible.

I had made several designs, none of which pleased me. Just when I was going to throw down the last one in discouragement, the painter Georges Clairin, who came to see me, begged me not to do so. And my good friend, Mathieu Mensiner, who was a man of talent, also joined his voice against the destruction of my design.

Excited by their encouragement I decided to push on with the work and to make a large group. I asked Lourdier if he knew any tall, bony old woman, and he sent me two, but neither of them suited me. Then I asked all my painter and sculptor friends, and during eight days all sorts of old and infirm women came for my inspection. I fixed at last on a charwoman who was about sixty years old. She was very tall and had very sharply cut features. When she came in I felt a slight sentiment of fear. The idea of remaining alone with this female gendarme for hours together made me feel uneasy. But when I heard her speak I was more comfortable. Her timid, gentle voice and frightened gestures, like a shy young girl, contrasted strangely with the build of the poor woman. When I showed her the design she was stupefied: “Do you want me to have my neck and shoulders bare? I really cannot.” I told her that nobody ever came in when I worked and I asked to see her neck immediately.

Oh, that neck! I clapped my hands with joy when I saw it. It was long, emaciated, terrible. The bones literally stood out almost bare of flesh, the Adam’s apple looked as if it would come through the skin. It was just what I wanted. I went up to her and gently bared her shoulder. What a treasure I had found! the bones of the shoulder were entirely visible under the skin and she had two immense “salt cellars.” The woman was ideal for my work. She seemed destined for it. She blushed when I told her so. I asked to see her feet. She took off her thick boots and showed a dirty foot which had no character. “No,” I said, “thank you. Your feet are too small, I will take only your head and shoulders.”

After having fixed the price I engaged her for three months. At the idea of earning so much money for three months the poor woman began to cry and I felt so sorry for her that I told her she would not have to seek for work that winter, because she had already told me that she generally passed six months of the year in the country, at Sologne, near her grandchildren.

Having found the grandmother I now needed the grandchild. I then had passed in review before me a whole army of little Italians, professional models. There were some lovely children, real little Jupins. The mothers undressed their children in one moment and the children posed quite naturally and took attitudes which showed off their muscles and the development of the torso. I chose a fine little boy of seven years, but who looked more like nine. I had already had the workmen in to put up the scaffolding required to make it sufficiently stable to sustain the necessary weight. Enormous iron supports were fixed into the plaster by bolts, and pillars of wood and iron wherever needed. The skeleton of a large piece of sculpture looks like a giant trap put up to catch rats and mice by the thousand.

I gave myself up to this enormous work with the courage of ignorance. Nothing discouraged me. Often I worked on till midnight, sometimes till four o’clock in the morning. And as one, humble gas burner was totally insufficient for working by, I had a crown or rather a silver circlet made, each bud of which was a candlestick with a candle burning, those of the back row a little higher than those of the front; and with this help I was able to work almost without ceasing. I had no watch or clock in the room, as I wished to ignore time altogether. Then my maid would come to seek me. How many times I have gone without lunch or dinner! Then I would perhaps faint and so be compelled to send for something to eat to restore my strength.

SARAH BERNHARDT AT WORK ON HER “MÊDÉE.”

I had almost finished my group, but I had done neither the feet nor the hands of the grandmother. She was holding her little dead grandson on her knees, but her arms had no hands and her legs had no feet. I looked in vain for the hands and the feet of my ideal, large and bony. One day when my friend Martel came to see me at my studio and to look at this group which was much talked of, I had an inspiration: Martel was big, and thin enough to make Death jealous. I watched him walking round my work. He was looking at it as a connoisseur. But I was looking at him. Suddenly I said:

“My dear Martel, I beg you ... I beseech you ... to pose for the hands and feet of my grandmother.”

He burst out laughing, and with perfectly good grace took off his shoes and took the place of my model.

He came ten days running and gave me three hours each day. Thanks to him I was able to finish my group. I had it molded and sent to the Salon (1876) where it had a veritable success. Is there any need to say that I was accused of having got some one else to make this group for me? I asked one critic to meet me. This was no other than Jules Claretie, who had declared that this work, which was very interesting, could not have been done by me. Jules Claretie excused himself very politely and that was the end of it.

The jury, after being fully informed on the subject, awarded me “honorable mention,” and I was wild with joy.

I was very much criticised, but also very much praised. Nearly all the criticisms were directed to the neck of my old Breton woman—that neck on which I had worked with such eagerness.

The following is from an article by Réné Delorme:

“The work of Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt deserves to be studied in detail. The head of the grandmother, well worked out as to the profound wrinkles it bears, expresses that intense sorrow in which everything else counts as nothing. The only reproach I have to bring against this artist is that she has brought too much into prominence the muscles of the neck of the old grandmother. This shows a lack of experience. She is pleased with herself for having studied anatomy so well and is not sorry for the opportunity of showing it. It is,” etc., etc....

Certainly this gentleman was right—I had studied anatomy eagerly and in a very amusing manner. I had had lessons from Doctor Parrot who was so good to me. I had continually with me a book of anatomical designs, and when I was at home I stood before the glass and said suddenly to myself, putting my finger on some part of my body: “Now, then, what is that?” I had to answer immediately, without hesitation, and when I hesitated I compelled myself to learn by heart the muscles of the head or the arm and did not sleep till this was done.

A month after the exhibition there was a reading of Parodi’s play, “Rome Vaincue,” at the Comédie Française. I refused the rôle of the young vestal Opïmia, which had been allotted to me, and energetically demanded that of Posthumia, an old blind Roman woman with a superb and noble face. No doubt there was some connection in my mind between my old Breton weeping over her son, and the august patrician claiming pardon for her granddaughter.

Perrin was at first astounded. Afterwards he acceded to my request. But his order-loving mind, and his taste for symmetry made him anxious about Mounet-Sully, who was also playing in the piece. He was accustomed to seeing Mounet-Sully and me playing the two heroes, the two lovers, the two victims. How was he to arrange matters so that we should still be the two ... together? Eureka! There was in the play an old idiot named Vastaepor, who was quite unnecessary for the action of the piece, but had been brought in to satisfy Perrin. “Eureka!” cried the director of the Comédie, “Mounet-Sully shall play Vestaepor!” Equilibrium was restored. The God of the bourgeois was content.

The piece, which was really quite mediocre, obtained a big success at the first presentation (27th September, 1876), and personally I was very successful in the fourth act. The crowd was decidedly in my favor in spite of everything and everybody.

The performance of “Hernani” made me more the favorite of the public than ever. I had already gone through it with Victor Hugo and it was a real pleasure to me to visit the great poet each day. I had never discontinued my visits to him, but I was never able to have any conversation with him in his own house. There were always men in red ties gesticulating, or women in tears reciting. He was very good; he listened to me with half-closed eyes and I thought he was asleep. Then when I stopped he roused up at the silence and said a consoling word, for Victor Hugo would not have promised to hear me without keeping his word. He was not like me; I promise everything with the firm intention of keeping my promises, and two hours after I have forgotten all about them. If anybody reminds me of what I have promised I tear my hair and to make up for my forgetfulness I say anything, I buy presents, in fact I complicate my life with useless worries. It has always been so and always will.

As I was grumbling one day to Victor Hugo that I never could have a chance of talking with him, he invited me to lunch, saying that after lunch we could talk together alone. I was delighted with this lunch, to which Paul Maurice the poet, Léon Gladel, Gustave Doré and the Cummunard X— (a Russian lady whose name I do not remember) were also invited. In front of Victor Hugo sat Mme. Drouet, the friend of his unlucky days. But what a horrible lunch we had! It was really bad and badly served. My feet were frozen by the draughts from the three doors, which fitted badly, and one could positively hear the wind blowing under the table. Near me was Mr. X——, the German architect, who is to-day a very successful man. This man had such dirty hands and ate so badly that he made me feel sick. I met him afterwards at Berlin. He is now quite clean and proper, and I believe an Imperialist. But the uncomfortable feeling this uncongenial neighbor inspired in me, the cold draughts blowing on my feet, the boredom I was afflicted with—all reduced me to a state of positive suffering and I lost consciousness. When I recovered I found myself on a couch, my hand in that of Mme. Drouet and in front of me, sketching me, Gustave Doré.

“Oh, don’t move,” he cried, “you are so pretty like that!” These words, though they were so inappropriate, pleased me, nevertheless, and I complied with the wish of the great artist. From that day we were the best of friends.

I left the house of Victor Hugo without saying good-by to him, a trifle ashamed of myself. The next day he came to see me. I told him some tale to account for my illness and I saw no more of him except at the rehearsals of “Hernani.”

The first performance of “Hernani” took place on the 21st November, 1877. It was a triumph alike for the author and the actors. “Hernani” had already been played ten years earlier, but Delaunay, who then took the part of Hernani, was the exact contrary of what this part should have been. He was neither epic, romantic, nor poetic. He had not the style of these grand times. He was charming, gracious, and with a perpetual smile, of middle height, with studied movements, ideal in Musset, perfect in Emile Augier, charming in Molière, but execrable in Victor Hugo.

Bressant, who took the part of Charles-Quint, was worst of all. His amiable and flabby style and his weak and wandering eyes effectively prevented all grandeur. His two enormous feet, generally half hidden under his trousers, took on immense proportions. I could see nothing else. They were very large, flat, and slightly turned in at the toes. They were a nightmare! But think of their possessor repeating the admirable couplet of Charles-Quint to the shade of Charlemagne! It was absurd! The public coughed, wriggled, and showed that they found the whole thing painful and ridiculous.

In our performance (in 1877) it was Mounet-Sully in all the splendor of his talent who played Hernani. And it was Worms, that admirable artiste who played Charles-Quint—and how well he took the part! How he rolled out the lines! What a splendid diction he had! This performance of the 21st of November, 1877, was a triumph. The public received me very well in my rôle. I played Doña Sol. Victor Hugo sent me this letter:

MADAME: You have been great and charming; you have moved me—me, the old man, and at one part, while the public whom you had enchanted cheered you, I wept. This tear which I shed for you, and through you, is at your feet, where I place myself.

VICTOR HUGO.

With this letter came a small box containing a fine chain bracelet, from which hung one diamond drop. I lost this bracelet at the rich nabob’s, Alfred Sassoon. He would have given me another, but I refused. He could not give me back the tear of Victor Hugo.

My success at the Comédie was assured, and the public treated me as a spoiled child. My friends were a little jealous of me. Perrin made trouble for me at every turn. He had a sort of friendship for me, but he could not believe that I could get on without him, and as he always refused to do as I wanted I did not go to him for anything. I sent a letter to the Ministère and I always won my cause.