CHAPTER XXIV

PREPARATIONS FOR AMERICA

My success in “Froufrou” was so marked that it filled the void left by Coquelin, who, after having signed, with the consent of Perrin, with Messrs. Mayer and Hollingshead, declared that he could not keep his engagements. It was a nasty trick of Jarnac’s by which Perrin hoped to injure my London performances. He had previously sent Got to me to ask officially if I would not come back to the Comédie. He said I should be permitted to make my American tour and that everything would be arranged on my return. But he should not have sent Got. He should have sent Worms or Le petit père Franchise—Delaunay. The one might have persuaded me by his affectionate reasoning, and the other by the falsity of arguments presented with such grace that it would have been difficult to refuse.

Got declared that I should be only too happy to come back to the Comédie on my return from America; “for you know,” he added, “you know, my little one, that you will die in that country. And if you come back you will perhaps be only too glad to return to the Comédie Française, for you will be in a bad state of health, and it will take some time before you are right again. Believe me, sign, and it is not we who will benefit by that, but you!”

“I thank you,” answered I, “but I prefer to choose my hospital myself on my return. And now you can go and leave me in peace.” I fancy I said: “Get out!”

That evening he was present at a performance of “Froufrou” and came to my dressing-room and said:

“You had better sign, believe me! And come back to commence with ‘Froufrou’! I will promise you a happy return!”

I refused and finished my performances in London without Coquelin.

The average of the receipts was 9,000 francs, and I left London with regret—I who had left it with so much pleasure the first time. But London is a city apart; its charm unveils little by little. The first impression for a Frenchman or woman is that of keen suffering, of mortal ennui. Those tall houses with sash windows without curtains; those ugly monuments, all in mourning with the dust and grime, and black with greasy dirt; those flower sellers at the corners of all the streets with faces sad as the rain and bedraggled feathers in their hats and lamentable clothing; the black mud of the streets; the low sky; the funereal mirth of drunken women hanging on to men just as drunk; the wild dancing of disheveled children round the street organs, as numerous as the omnibuses—all that caused, twenty-five years ago, an indefinite suffering to a Parisian. But little by little one finds that the profusion of the squares is restful to the eyes; that the beauty of the aristocratic ladies effaces the image of the flower sellers.

The constant movement of Hyde Park, and especially of Rotten Row, fills the heart with gayety. The broad English hospitality which was manifested from the first moment of making an acquaintance; the wit of the men, which compares favorably with the wit of Frenchmen; and their gallantry, much more respectful and therefore much more flattering, left no regrets in me for French gallantry.

But I prefer our pale mud to the London black mud; and our windows opening in the centre to the horrible sash windows. I find also that nothing marks more clearly the difference of character of the two nations than their respective windows. Ours open wide, the sun enters into our houses even to the heart of the dwelling, the air sweeps away all the dust and all the microbes. They shut in the same manner, simply, as they open.

English windows open only halfway, either the top half or the bottom half. One may even have the pleasure of opening them a little at the top and a little at the bottom, but not at all in the middle. The sun cannot enter openly, nor the air. The window keeps its selfish and perfidious character. I hate the English windows. But now I love London, and—is there any need to add?—its inhabitants. Since my first visit I have returned there twenty-one times, and the public has always remained faithful and affectionate.

After this first test of my freedom, I felt more sure of life than before. Although I was very weakly of constitution, the possibility of doing as I wanted without let or hindrance and without control, calmed my nerves; and with a strengthened nervous system, my health, which had been weakened by perpetual irritations and by excessive work, recovered its tone. I reposed on the laurels which I had gathered myself—and I slept better. Sleeping better I commenced to eat better. And great was the astonishment of my little court when they saw their idol come back from London round and rosy.

I remained several days in Paris, then I set out for Brussels, where I was to play “Adrienne Lecouvreur” and “Froufrou.”

The Belgian public—by which I mean the Brussels public—is the most like our own. In Belgium I never feel that I am in a strange country. Our language is the language of the country; the horses and carriages are always in perfect taste; the fashionable women resemble our own fashionable women; cocottes abound; the hotels are as good as in Paris; the cab horses are as poor; the newspapers are as spiteful. Brussels is gossiping Paris in miniature.

I played, for the first time, at the Monnaie and I felt uncomfortable in this immense and frigid theater. But the benevolent enthusiasm of the public soon warmed me and I shall never forget the four evenings I gave there.

Then I set out for Copenhagen, where I was to give five performances at the Theater Royal.

Our arrival, which was anxiously expected, doubtless, really frightened me. More than two thousand persons who were assembled in the station when the train came in, gave a hurrah so terrible that I did not know what was happening. But when M. De Fallesen, manager of the Theater Royal, and the first chamberlain of the king, entered my compartment and begged me to show myself at the window to gratify the curiosity of the public, the hurrahs began again, and then I understood. But a dreadful anxiety now took possession of me. I could never, I was sure, rise to what was expected from me. My slender frame would inspire disdain in those magnificent men and those splendid and healthy women. I stepped out of the train so diminished by comparison that I had the sensation of being nothing more than a breath of air; and I saw the crowd, submissive to the police, divide into two compact lines, leaving a large way for my carriage. I passed slowly through this double hedge of sympathetic sightseers, who threw me flowers and kisses and lifted their hats to me. I have had afterwards, in the course of my long career, many triumphs, receptions and ovations; but my reception by the Danish people remains one of my most cherished souvenirs. The living hedge lasted till we reached the Hotel d’Angleterre where I went in, after once more thanking the sympathetic friends who surrounded me.

In the evening, the King and Queen and their daughter, the Princess of Wales, were present at the first performance of “Adrienne Lecouvreur.”

This is what the Figaro of the 16th August, 1880, said:

“Sarah Bernhardt has played ‘Adrienne Lecouvreur’ with a tremendous success before a magnificent public. The royal family, the King and the Queen of the Hellènes, as well as the Princess of Wales, were present at the performance. The Queens threw their bouquets to the French artiste, midst applause. It was an unprecedented triumph. The public was delirious. To-morrow ‘Froufrou’ will be played.”

The performances of “Froufrou” were equally successful. But as I was playing only every other day I wanted to visit Elsinore. The King placed the royal steamer at my disposal for this little journey.

I had invited all my company.

M. De Fallesen, the first chamberlain and manager of the Theater Royal, caused a magnificent lunch to be served for us, and accompanied by the principal notabilities of Denmark we visited Hamlet’s tomb, the Spring of Ophelia, and the Castle of Marienlyst. Then we went over the Castle of Cronburg. I regretted my visit to Elsinore. The reality did not come up to the expectation. The so-called Tomb of Hamlet is represented by a small column, ugly and mournful looking; there is little verdure and the desolate sadness of deceit without beauty. They gave me a little water from the Spring of Ophelia to drink and the Baron de Fallesen broke the glass without allowing anyone else to drink from the spring.

I returned from this very ordinary journey feeling rather sad. Leaning against the side of the vessel I watched the water gliding past, when I noticed a few rose petals emerge, which carried by an invisible current were borne against the sides of the boat; then the petals increased to thousands and in the mysterious sunset rose the melodious chant of the sons of the North. I looked up. In front of us, rocked on the water by the evening breeze, was a pretty boat with outspread sails: a score of young men, throwing handfuls of roses into the waters, which were carried to us by the little wavelets, were singing the marvelous legends of past centuries. And all that was for me: all those roses, all that love, all that musical poetry. And the setting sun—it was also for me. And in this fleeting moment which brought near me all the beauty of life, I felt myself very near to God.

The following day, at the close of the performance, the King had called me before him into the royal box and he decorated me with a very pretty Order of Merit adorned with diamonds. He kept me some time in his box asking me about a lot of things. I was presented to the Queen and I noticed immediately that she was somewhat deaf. I was rather embarrassed, but the Queen of Greece came to my rescue. She was beautiful, but much less so than her lovely sister, the Princess of Wales. Oh, that adorable and seductive face! with the eyes of a child of the North and classic features of virginal purity, a long supple neck that seemed made for queenly bows, a sweet and almost timid smile. The indefinable charm of this princess made her so radiant that I saw nothing but her, and I left the box leaving behind me, I fear, but a doubtful opinion of my intelligence with the royal couples of Denmark and Greece.

The evening before my departure I was invited to a grand supper. Fallesen made a speech, and thanked us in a very well-turned manner for the French week which we had given in Denmark.

Robert Walt made a very cordial speech on behalf of the Press, very short but very sympathetic. Our ambassador, in a few courteous words, thanked Robert Walt, and then to the general surprise, Baron Magnus, the Prussian Minister, rose, and in a loud voice, turning to me, he said: “I drink to France, which gives us such great artistes! to France, la belle France, whom we all love so much!”

Hardly ten years had passed since the terrible war. French men and women were still suffering; their wounds were not healed.

Baron Magnus, a really amiable and charming man, had, from the time of my arrival in Copenhagen, sent me flowers with his card. I had sent back the flowers and begged an attaché of the English Embassy, Sir Francis, I believe, to ask the German baron not to renew his gifts. The baron laughed good-naturedly and waited for me as I came out of my hotel. He came to me with outstretched hands and spoke kindly and reasonable words. Everybody was looking at us and I was embarrassed. It was evident that he was a kind man. I thanked him, touched in spite of myself, by his frankness, and I went away quite undecided as to what I really felt. Twice he renewed his visit, but I did not receive him, but only bowed as I left my hotel. I was somewhat irritated at the tenacity of this amiable diplomatist. On the evening of the supper, when I saw him take the attitude of an orator, I felt myself grow pale. He had barely finished his little speech, when I jumped to my feet and cried: “Let us drink to France—but to the whole of France, Monsieur l’Embassadeur de Prusse!” I was nervous, sensational, and theatrical, without intending it.

It was like a bolt from the blue.

The orchestra of the court which was placed in the upper gallery began playing the “Marseillaise.” At this time the Danes hated the Germans. The supper room was suddenly deserted as if by enchantment.

I went up to my rooms not wishing to be questioned. I had gone too far. Anger had made me say more than I intended. Baron Magnus did not deserve this tirade. And also my instinct forewarned me of results to follow. I went to bed angry with myself, with the baron, and with all the world.

About five o’clock in the morning I commenced to doze, when I was awakened by the growling of my dog. Then I heard some one knocking at the door of the salon. I called my maid, who woke her husband, and he went to open the door. An attaché from the French Embassy was waiting to speak to me on urgent business. I put on an ermine tea gown and went to see the visitor.

“I beg you,” he said, “to write a note immediately, to explain that the words you said were not meant.... The Baron Magnus, whom we all respect, is in a very awkward situation and we are all unhappy about it. Prince Bismarck is not to be trifled with and it may be very serious for the baron.”

“Oh! I assure you, monsieur, I am a hundredfold more unhappy about it than you, for the baron is a good and charming man; he is short of political tact, and in this case it is excusable because I am not a woman of politics. I was lacking in coolness. I would give my right hand to repair the ill.”

“We don’t ask you for so much as that. And that would spoil the beauty of your gestures!” (He was French, you see). “Here is the rough copy of a letter; will you take it, rewrite it, sign it and everything will be at an end.”

But that was unacceptable. The wording of this letter gave twisted and rather cowardly explanations. I rejected it and after several attempts to rewrite it, I gave up in despair and did nothing.

Three hundred persons had been present at the supper, in addition to the royal orchestra and the attendants. Everybody had heard the amiable but awkward speech of the baron. I had replied in a very excited manner. The public and the Press had all been witnesses of my tirade; we were the victims of our own foolishness, the baron and myself. If such a thing were to happen at the present time I should not care a pin for public opinion, and I should even take pleasure in ridiculing myself in order to do justice to a brave and gallant man. But at that time I was very nervous, and uncompromisingly patriotic. And also, perhaps, I thought I was some one of importance. Since then life has taught me that if one has to be famous it can only be after Death has set his seal to life. To-day I am going down the hill of life and I regard gaily all the pedestals on which I have been lifted up, and there have been so many of them that their fragments, broken by the same hands that had raised them, have made me a solid pillar, from which I look out on life, happy with the past and expectant of the future.

My stupid vanity had wounded one who meant me well, and this incident has always left in me a feeling of remorse and chagrin.

I left Copenhagen in the midst of applause and repeated cries of Vive la France! From all the windows hung the French flag, fluttering in the breeze, and I felt that this was not only for me, but against Germany—I was sure of it.

Since then the Germans and the Danes are solidly united and I am not certain that several Danes do not still bear me malice because of this incident of the Baron Magnus.

I came back to Paris to make my final preparations for my journey to America. I was to set sail the 15th of October.

One day in August, I was having a reception of all my friends, who came to see me in full force because I was about to set out for a long journey.

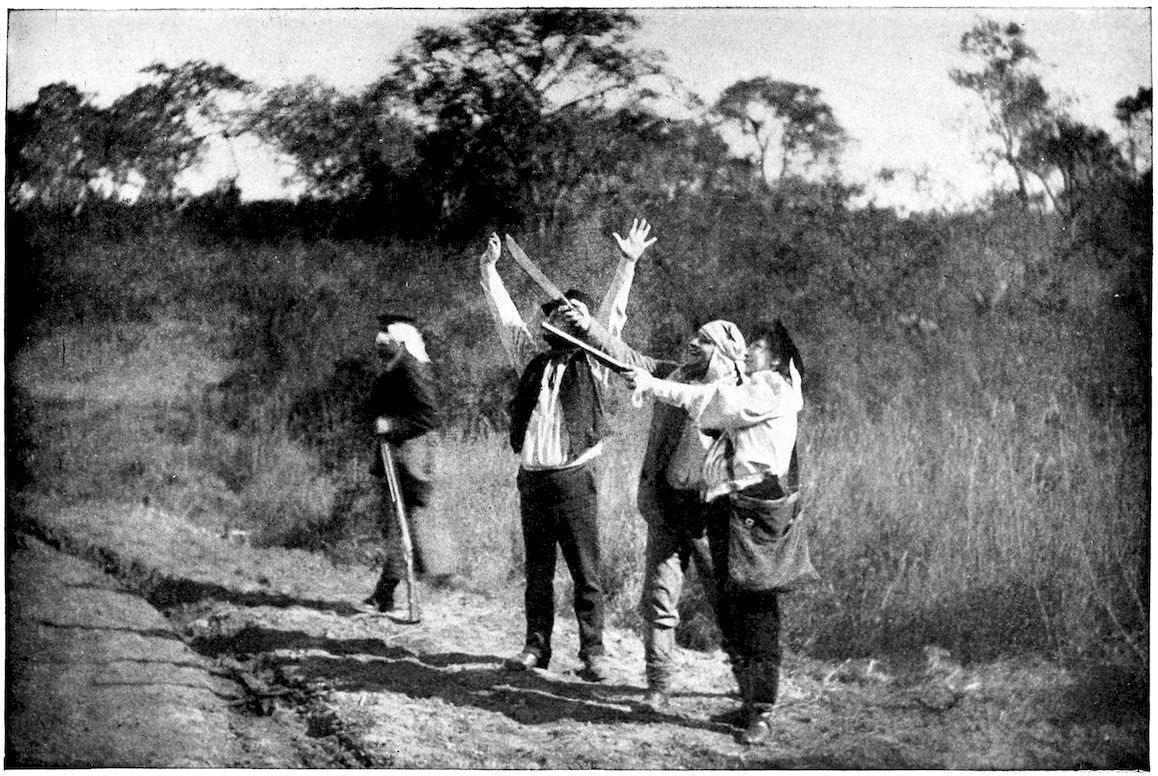

SARAH BERNHARDT AND MEMBERS OF HER COMPANY OUT SHOOTING.

Among the number were Girardin, Count Kapenist, Marshal Canrobert, Georges Clairin, Arthur Meyer, Duquesnel, the beautiful Augusta Holmes, Raymond de Montbel, Nordenskyjold, O’Connor, and other friends. I chatted gaily, happy to be surrounded by so many tender and intellectual friends. Girardin did all he could to persuade me not to undertake this journey to America. He had been the friend of Rachel and told me the sad end of her journey. Arthur Mayer was of opinion that I ought always to do what I thought best. The other friends discussed the affair. That admirable man, whom France will always worship, Canrobert, said how much he should miss and regret these intimate causeries at our five o’clock teas.

“But,” said he, “we have not the right to try, in our affectionate selfishness, to hinder our young friend from doing all she can in the strife. She is of a combative nature.”

“Ah, yes!” I cried, “I am born for the strife, I feel it. Nothing pleases me like having to master a public—perhaps hostile—who have read and heard all that the Press have to say against me. But I am sorry that I cannot play, not only in Paris, but in all France, my two big successes, ‘Adrienne’ and ‘Froufrou.’”

“As to that, you can count on me,” cried Félix Duquesnel. “My dear Sarah, you had your first successes with me and it is with me that you will have your last.”

Everybody exclaimed and I jumped up.

“Why wait,” said he, “for the last successes until you come back from America? If you will consent you can count on me for everything. I will obtain, at any price, theaters in all the large towns and we will give twenty-five performances during the month of September. As to the money conditions, they will be of the simplest: twenty-five performances—50,000 francs. To-morrow I will give you the half of this sum and you shall sign the contract, so that you will not have time to change your mind.”

I clapped my hands joyfully. All the friends who were there begged Duquesnel to send them, as soon as possible, a plan of the tour, for they all wanted to see me in the two plays in which I had carried off the laurels in England and Belgium and Denmark.

Duquesnel promised to send them the details of the tour, and it was settled that their visits would be drawn by lot from a little bag and each town marked with the date and the name of the play.

A week later, Duquesnel, with whom I had signed the contract, returned with the entire tour planned out and all the company engaged. It was almost miraculous.

The performances were to commence on Saturday the 4th of September, and there were to be twenty-five of them; and the whole, including the day of departure and the day of return, was to last twenty-eight days, which caused this tour to be called “The twenty-eight days of Sarah Bernhardt,” like the twenty-eight days of a citizen who is obliged to undertake his military service.

The little tour was most successful, and I never enjoyed myself more than in this artistic promenade. Duquesnel organized excursions and fêtes outside the towns.

At first he had prepared, thinking to please me, some visits to the sights of the towns. He had written beforehand from Paris fixing dates and hours. The guardians of the different museums, art galleries, etc., had offered to point out to me the finest objects in their collections and the mayors had prepared the visits to the churches and celebrated buildings.

When, on the eve of our departure, he showed us the heap of letters, each giving a most amiable affirmative, I shrieked. I hate seeing public buildings, and having them explained to me. I know most of the public sights of France, but I have visited them when I felt inclined and with my own chosen friends. As to the churches and other buildings, I find them very tiresome. I cannot help it—it really wearies me to see them. I can admire their outline in passing, or when I see them silhouetted against the setting sun, that is all right, but further than that I will not go. The idea of entering these cold spaces, while some one explains their absurd and interminable history, of looking up at their ceilings with craning neck, of cramping my feet by walking unnaturally over highly waxed floors, of being obliged to admire the restoration of the left wing, (that they would have done better by letting crumble to ruins,) to have to wonder at the depth of some moat which once used to be full of water but is now dry as the east wind ... all that is so tiresome it makes me want to howl. From my earliest childhood I have always detested houses, castles, churches, towers, and all buildings higher than a mill. I love low buildings, farms, huts, and I positively adore mills, because these little buildings do not obstruct the horizon. I have nothing to say against the Pyramids, but I would a hundred times rather they had never been built.

I begged Duquesnel to send telegrams at once to all the notabilities who had been so obliging. We passed two hours over this task and the 3rd of September I set out, free, joyful, and content.

My friends came to see me while I was on tour, in accordance with the lots they had drawn, and we had picnics by coach into the surrounding country in all the towns in which I played.

I came back to Paris on the 30th of September, and had only just time to prepare for my journey to America. I had been only a week at Paris when I had a visit from M. Bertrand, who was then director of the Variétés. His brother was director of the Vaudeville in partnership with Raymond Deslandes. I did not know Eugène Bertrand, but I received him at once, for we had mutual friends.

“What are you going to do when you come back from America?” he asked me, after we had exchanged greetings.

“I really don’t know.... Nothing. I have not thought of anything.”

“Well, I have thought of something for you. And if you like to make your return to Paris in a play of Victorien Sardou’s, I will sign with you at once for the Vaudeville.”

“Ah!” I cried. “The Vaudeville! What are you thinking of? Raymond Deslandes is the manager and he hates me like poison because I ran away from the Gymnase the day following the first performance of his play: ‘Un Mari qui Lance sa Femme.’ His play was ridiculous, and I was even more ridiculous than his play in the part of a young Russian lady addicted to dancing and eating sandwiches. That man will never engage me!”

He smiled. “My brother is the partner of Raymond Deslandes. My brother ... to put it plainly, is myself. All the money brought by us is mine! I am the sole master! What do you want to earn?”

“But...? I really don’t know.”

“Will fifteen hundred francs per performance suit you?”

I looked at him in stupefaction, not quite sure if he was in his right mind.

“But, monsieur, if I do not succeed you will lose money, and I cannot agree to that.”

“Do not be afraid,” he said. “I can assure you it will be a success—a colossal success. Will you sign? And I will also guarantee you fifty performances!”

“Oh, no, never! I will sign willingly, for I admire the talent of Victorien Sardou, but I do not want any guarantee. Success will depend on Victorien Sardou, and after him on me. So I sign and thank you for your confidence.”

At my afternoon teas I showed the new contract to my friends, and they were all of opinion that luck was on my side in the matter of my resignation.

Only three days remained to me in Paris. My heart was sore at the idea of leaving France, for many sorrowful reasons.... But in these memoirs I have put to one side all that touches the inner part of my life. There is one “I” which lives another life, and whose sensations, sorrows, joys, and griefs are born and die for a very small number of hearts.

But I felt the need of another atmosphere, of vaster space, of other skies.

I left my little boy with my uncle who had five boys of his own. His wife was a rigid Protestant, but kind, and my cousin Louise, their eldest daughter, was witty and highly intelligent. She promised me to be on the lookout and to let me know at once if there was anything I ought to know.

BUST OF VICTORIEN SARDOU, BY SARAH BERNHARDT.

Up to the last moment, people in Paris did not believe that I would really go. I had such uncertain health that it seemed folly to undertake such a journey. But when it was quite certain that I was going, there was a general outburst from my enemies and the hue and cry after me was in full swing. I have now under my eyes the specimens of insanity, calumnies, lies, and stupidities, burlesque portraits, doleful pleasantries, good-bys to the darling, the idol, the star, the zimm! boum! boum! etc., etc.... It was all so absolutely idiotic that I was confounded. I had not read the greater part of these articles, but my secretary had orders to cut them out and paste them in little notebooks, whether favorable or unfavorable. It was my godfather who had commenced doing this when I entered the Conservatoire and after his death I had it continued.

Happily I find, in these thousands of lines, fine and noble words—words written by J. J. Weiss, Zola, Emile de Girardin, Jules Vallés, Jules Lemaître, etc.; and beautiful verses full of grace and justice, signed Victor Hugo, Francois Coppée, Richemin, Haroucourt, Henri de Bornier, Catulle Mendès, Parodi, and later Edmond Rostand.

I neither could nor would suffer unduly from the calumnies and lies; but I confess that the kindly appreciation and praises accorded me by the superior spirits afforded me infinite joy.