CHAPTER XXV

MY ARRIVAL IN AMERICA

The ship which was to take me away to other hopes, other sensations, and other successes was named L’Amérique. It was the unlucky boat, the boat that was haunted by the Gnome. All kinds of misfortunes, accidents, and storms had been its lot. It had been stranded for months with its keel out of water. Its stern had been staved in by an Iceland boat and it had foundered on the shoals of Newfoundland, I believe, and been set afloat again. Another time fire had broken out on it right in the Hâvre roadstead, but no great damage was done, and the poor boat had had a celebrated adventure which had made it ridiculous. In 1876 or 1877 a new pumping system was adopted and although this system had been in use by the English for a long time it was quite unknown aboard French boats. The captain very wisely decided to have these pumps worked by his crew so that in case of any danger the men would be ready to manipulate them easily. The experiment had been going on for a few minutes when one of the men came to inform the captain that the hold of the ship was filling with water, and no one could discover the cause of it. “Go on pumping!” shouted the captain. “Hurry up! Pump away!” The pumps were worked frantically and the result was that the hold filled entirely, and the captain was obliged to abandon the ship after seeing the passengers safely off in the boats. An English whaler met the ship two days after, tried the pumps which worked admirably but in the contrary way to that indicated by the French captain. This slight error cost the Compagnie Transatlantique £48,000 salvage money, and when they wanted to start the ship again and passengers refused to go by it they offered my impresario, M. Abbey, excellent terms. He accepted them, and very intelligent he was, for in spite of all prognostications the boat had paid her tribute.

I had hitherto traveled very little and I was wild with delight.

On the 15th of October, 1880, at six o’clock in the morning, I entered my cabin. It was a large one and hung with light red rep embroidered with my initials. What a profusion of the letters S. B.! Then there was a large brass bedstead brightly polished, and flowers everywhere. Adjoining mine was a very comfortable cabin for my petite dame, and leading out of that was one for my maid and her husband. All the other persons I employed were at the other end of the ship. The sky was misty, and the sea gray, with no horizon. I was on my way over there, beyond that mist which seemed to unite the sky and the water in a mysterious rampart. The clearing of the deck for the departure upset everyone and everything. The rumbling of the machinery, the boatswain’s call, the bell, the sobbing and the laughter, the creaking of the ropes, the shrill shouting of the orders, the terror of those who were only just in time to catch the boat, the “Halloo!” “Look out!” of the men who were pitching the packages from the port into the hold, the sound of the laughing waves breaking over the side of the boat, all this mingled together made the most frightful uproar, tiring the brain so that its own sensations were all vague and bewildered. I was one of those who, up to the last moment enjoyed the “Good-bys,” the handshakings, the plans about the return, and the farewell kisses, and when it was all over flung themselves sobbing on their bed.

For the next three days I was in utter despair, weeping bitter tears, tears that scalded my cheeks. Then I began to get calm again, my will power triumphed over my grief. On the fourth day I dressed at seven o’clock and went on deck to have some fresh air. It was icy cold and as I walked up and down I met a lady dressed in black with a sad, resigned face. The sea looked gloomy and colorless and there were no waves. Suddenly a wild billow dashed so violently against our boat that we were both thrown down. I immediately clutched hold of the leg of one of the benches, but the unfortunate lady was flung forward. Springing to my feet with a bound I was just in time to seize hold of the skirt of her dress, and with the help of my maid and a sailor, we managed to prevent the poor woman from falling head first down the staircase. Very much hurt, though, she was, and a trifle confused; she thanked me in such a gentle, dreamy voice that my heart began to beat with emotion.

“You might have been killed, madame,” I said, “down that horrible staircase.”

“Yes,” she answered, with a sigh of regret, “but it was not God’s will. Are you not Madame Hessler?” she continued, looking earnestly at me.

“No, madame,” I answered, “my name is Sarah Bernhardt.”

She stepped back and drawing herself up, her face very pale and her brows knitted, she said in a mournful voice, a voice that was scarcely audible: “I am the widow of President Lincoln.”

I, too, stepped back, and a thrill of anguish ran through me, for I had just done this unhappy woman the only service that I ought not to have done her—I had saved her from death. Her husband had been assassinated by an actor, Booth, and it was an actress who had now prevented her from joining her beloved husband. I went back again to my cabin and stayed there two days, for I had not the courage to meet that woman for whom I felt such sympathy, and to whom I should never dare to speak again.

On the 22d we were surprised by an abominable snowstorm. I was called up hurriedly by Captain Jonclas. I threw on a long ermine cloak and went on to the bridge. It was perfectly stupefying and at the same time fairylike. The heavy flakes met each other with a hiss in their mad waltzing provoked by the wind. The sky was suddenly veiled from us by all this whiteness which fell round us in avalanches, completely hiding the horizon. I was facing the sea and, as Captain Jonclas pointed out to me, we could not see a hundred yards in front of us. I then turned round and saw that the boat was as white as a seagull; the ropes, the cordage, the nettings, the portholes, the shrouds, the whalers, the deck, the sails, the ladders, the funnels, the airholes—everything was white. The sea was black and the sky was black. The boat alone was white, floating along in this immensity. There was a contest between the high funnel, sputtering forth with difficulty its smoke through the wind which was rushing wildly into its great mouth, and the prolonged shrieks of the siren. The contrast was so extraordinary between the virgin whiteness of this boat and the infernal uproar it made that it seemed to me as if I had before me an angel in a fit of hysterics.

In the evening of that strange day the doctor came to tell me of the birth of a child among the immigrants, in whom I was deeply interested. I went at once to the mother and did all I could for the poor little creature who had just come into the world. Oh, the dismal moans in that dismal night in the midst of all that misery! Oh, that first strident cry of the child affirming its will to live in the midst of all these sufferings, of all these hardships, and of all these hopes! Everything was there mingled together in that human medley—men, women, children, rags and preserves, oranges and basins, heads of hair and bald pates, half-open lips of young girls and tightly closed mouths of shrewish women, white caps and red handkerchiefs, hands stretched out in hope and fists clenched against adversity. I saw revolvers half concealed under the rags, knives in the men’s belts. A sudden roll of the boat showed us the contents of a parcel that had fallen from the hands of a rascally looking fellow with a very decided expression on his face, and a hatchet and a tomahawk fell to the ground. One of the sailors immediately seized the two weapons to take them to the purser. I shall never forget the scrutinizing glance of the man. He had evidently made a mental note of the features of the sailor, and I breathed a fervent prayer that the two might never meet in a solitary place.

I remember now with remorse the horrible disgust that took possession of me when the doctor handed the child over to me to wash. That dirty little red, moving, sticky object was a human being. It had a soul and would have thoughts. I felt quite sick and I could never again look at that child—although I was afterwards its godmother—without living over again that first impression. When the young mother had fallen asleep I wanted to go back to my cabin. The doctor helped me, but the sea was so rough that we could scarcely walk at all among the packages and immigrants. Some of them who were crouching on the floor watched us silently as we tottered and stumbled along like drunkards. I was annoyed at being watched by those malevolent, mocking eyes. “I say, doctor,” one of the men called out, “the sea water gets in the head like wine. You and your lady look as though you were coming back from a spree!” An old woman clung to me as we passed. “Oh, madame!” she said, “shall we be shipwrecked with the boats rolling like this? Oh, God! oh, God!” A tall fellow with red hair and beard came forward and laid the poor old woman down again gently. “You can sleep in peace, mother,” he said; “if we are shipwrecked I swear there shall be more, saved down here than up on the top.” He then came closer to me and continued in a defiant tone: “The rich folks ... first class, into the sea! ... the immigrants—seconds, in the boats!” As he uttered these words I heard a sly, stifled laugh from everywhere, in front of me, behind, at the side, and even from under my feet. It seemed to echo in the distance like the laughing behind the scenes on the stage. I drew nearer to the doctor and he saw that I was uneasy.

“Nonsense,” he said, laughing, “we should defend ourselves.”

“But how many could be saved,” I asked, “in case we were really in danger?”

“Two hundred—two hundred and fifty at the most with all the boats out, if all arrived safely.”

“But the purser told me that there were seven hundred and sixty immigrants,” I insisted, “and there are only a hundred and twenty passengers. How many do you reckon are the officers, the crew, and the servants?”

“A hundred and seventy,” the doctor answered.

“Then there are a thousand and fifty on board and you can save only two hundred and fifty?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then, I can understand the hatred of these immigrants whom you take on board like cattle and treat like negroes. They are absolutely certain that in case of danger they would be sacrificed.”

“But we should save them when their turn came.”

I glanced with horror at the man who was talking to me. He looked honest and straightforward and he evidently meant what he said. And so all these poor creatures who had been disappointed in life, and badly treated by society, would have no right to life until after we were saved, we the more favored ones! Oh, how I understood now the rascally looking fellow, with his hatchet and tomahawk! How thoroughly I approved at that moment of the revolvers and the knives hidden in the belts. Yes, he was quite right, the tall, red-haired fellow. We want the first places, always the first places ... and so we might have the first places! Into the water with us!

“Well, are you satisfied?” asked the captain who was just coming out of his cabin. “Has it gone off all right?”

“Yes, captain,” I answered, “but I am horrified.”

Jonclas stepped back in surprise....

“Good heavens, what has horrified you?” he asked.

“The way in which you treat your passengers ...”

He tried to put in a word, but I continued: “Why ... you expose us in case of a shipwreck....”

“We never have a shipwreck....”

“Good ... in case of a fire, then....”

“Good ... in case of submersion....”

“We never have a fire....”

“I give in,” he said, laughing. “To what do we expose you, madame?”

“To the very worst of deaths ... to a blow on the head with an ax, to a dagger thrust in our back, or merely to be flung into the water....”

He attempted to speak, but again I continued: “There are seven hundred and fifty immigrants below and there are scarcely three hundred of us, counting first-class passengers and the crew.... You have boats which might save two hundred persons and even that is doubtful....”

“Well?”

“Well, what about the immigrants?”

“We should save them before the crew.”

“But after us?”

“Yes, after you.”

“And you fancy that they would let you do it?”

“We have guns with which to keep them in order.”

“Guns ... guns for women and children.”

“No ... the women and children would take their turn first.”

“But that is idiotic,” I exclaimed, “it is perfectly absurd! Why save women and children if you are going to make widows and orphans of them? And do you believe that all those young men would resign themselves to their fate because of your guns? There are more of them than there are of you, and they are armed. Life owes them their revenge, and they have the same right that we have to defend the supreme moment. They have the courage of those who have nothing to lose and everything to gain in the struggle. In my opinion it is iniquitous and infamous that you should expose us to certain death and them to an obligatory and perfectly justified crime.”

The captain tried to speak, but again I persisted. “Without going as far as a shipwreck only fancy if we were to be tossed and bandied about for months on a raging sea. This has happened and might happen again.... You cannot possibly have food enough on board for a thousand people during two or three months.”

“No, certainly not,” put in the purser dryly. He was a very amiable man, but very touchy.

“Well, then, what should you do?” I asked.

“What would you do?” asked the captain, highly amused at the annoyed expression on the purser’s face.

“I ... oh! I should have a boat for immigrants and a boat for passengers, and I think that would be only just.”

“Yes, but it would be ruinous.”

“No, the one for wealthy people would be a steamer like this, and the one for emigrants a sailing vessel.”

“But that, too, would be unjust, madame, for the steamer would go more quickly than the sailing boat.”

“That would not matter at all,” I argued. “Wealthy people are always in a hurry and the poor never are. And then, considering what is awaiting them in the land to which they are going....”

“It is the Promised Land.”

“Oh! poor things ... poor things ... with their Promised Land—Dakota or Colorado! In the daytime they have the sun which makes their brains boil, scorches the ground, dries up the springs, and brings forth endless numbers of mosquitoes to sting their bodies and try their patience. The Promised Land! At night they have the terrible cold to make their eyes smart, to stiffen their joints, and ruin their lungs. The Promised Land! It is just death in some out-of-the-world place after fruitless appeals to the justice of their fellow countrymen. They will breathe their life out in a sob or in a terrible curse of hatred. God will have mercy on all of them, though, for it is piteous to think that all these poor creatures are delivered over with their feet bound by suffering, and their hands bound by hope, to the slave drivers who trade in white slaves. And when I think that the money is in the purser’s cash box which the slave driver has paid for the transport of all these poor creatures! Money that has been collected by rough hands or trembling fingers. Poor money economized, copper by copper, tear by tear. When I think of all this it makes me wish that we could be shipwrecked, that we could be all killed, and all of those saved.”

With these words I hurried away to my cabin to have a good cry, for I was seized with a great love for humanity and intense grief that I could do nothing, absolutely nothing!...

The following morning I awoke late, as I had not fallen asleep until near dawn. My cabin was full of visitors and they were all holding small parcels half concealed. I rubbed my sleepy eyes and could not quite understand the meaning of their invasion.

“My dear Sarah,” said Mme. Guérard, coming to me and kissing me, “don’t imagine that this day, your fête day, could be forgotten by those who love you.”

“Oh!” I exclaimed, “is it the 23d?”

“Yes, and here is the first of the remembrances from the absent ones.”

My eyes filled with tears and it was through a mist that I saw the portrait of that young being more precious to me than anything else in the world, with a few words in his own hand writing.... Then there were some presents from friends ... pieces of work from humble admirers. My little godson of the previous evening was brought to me in a basket, with oranges, apples, and tangerines all round him. He had a golden star on his forehead, a star cut out of some gold paper in which chocolate had been wrapped. My maid Félicie, and Claude, her husband, who were most devoted to me, had prepared some very ingenious little surprises. Presently there was a knock at my door and on calling out “Come in,” I saw, to my surprise, three sailors carrying a superb bouquet which they presented to me in the name of the whole crew. I was wild with admiration and wanted to know how they had managed to keep the flowers in such good condition. It was an enormous bouquet, but when I took it in my hands I let it fall to the ground in an uncontrollable fit of laughter. The flowers were all cut out of vegetables, but so perfectly done that the illusion was complete at a little distance. Magnificent roses were cut out of carrots, camellias out of turnips, small radishes had furnished sprays of rosebuds stuck on to long leeks dyed green, and all these relieved by carrot leaves artistically arranged to imitate the grassy plants used for elegant bouquets. The stalks were tied together with a bow of tri-colored ribbon. One of the sailors made a very touching little speech on behalf of his comrades, who wished to thank me for a trifling service rendered. I shook hands cordially and thanked them heartily and this was the signal for a little concert that had been organized in the cabin of my petite dame. There had been a private rehearsal with two violins and a flute, so that for the next hour I was lulled by the most delightful music, which transported me to my own dear ones, to my hall which seemed so distant to me at that moment, and for the first time since my departure I regretted having set out. This little fête, which was almost a domestic one, together with the music, had evoked the tender and restful side of my life, and the tears that all this called forth fell without grief, bitterness, or regret. I wept simply because I was deeply moved, and I was tired, nervous, and weary, and had a longing for rest and peace. I fell asleep in the midst of my tears, sighs, and sobs.

Finally, the boat stopped on the 27th of October, at half past six in the morning. I was asleep, worn out by three days and nights of wild storms. My maid had some difficulty in rousing me. I could not believe that we had arrived, and I wanted to go on sleeping until the last minute. I had to give in to the evidence, however, as the boat had stopped. This sudden arrival delighted me and everything seemed to be transformed in a minute. I forgot all my discomforts, and the weariness of the eleven days’ crossing. The sun was rising, pale but rose tinted, dispersing the mists and shining over the river. I had entered the New World in the midst of a display of sunshine. This seemed to me a good omen. I am so superstitious that if I had arrived when there was no sunshine I should have been wretched, and most anxious until after my first performance. It is a perfect torture to be superstitious to this degree and, unfortunately for me, I am ten times more so now than I was in those days, for besides the superstitions of my own country I have, thanks to my travels, added to my stock all the superstitions of the other countries. I know them all now and in any critical moment of my life they all rise up in armed legions, for or against me. I cannot walk a single step, or make any movement or gesture, sit down, go out, look at the sky or the ground, without finding some reason for hope or for despair until at last, exasperated by the trammels put upon my actions by my thought, I defy all my superstitions and just act as I want to. Delighted, then, with what seemed to me to be a good omen I began to dress gleefully. Mr. Jarrett had just knocked at my door.

“Do please be ready as soon as possible, madame,” he said, “for there are several boats, with the French colors flying that have come out to meet you.”

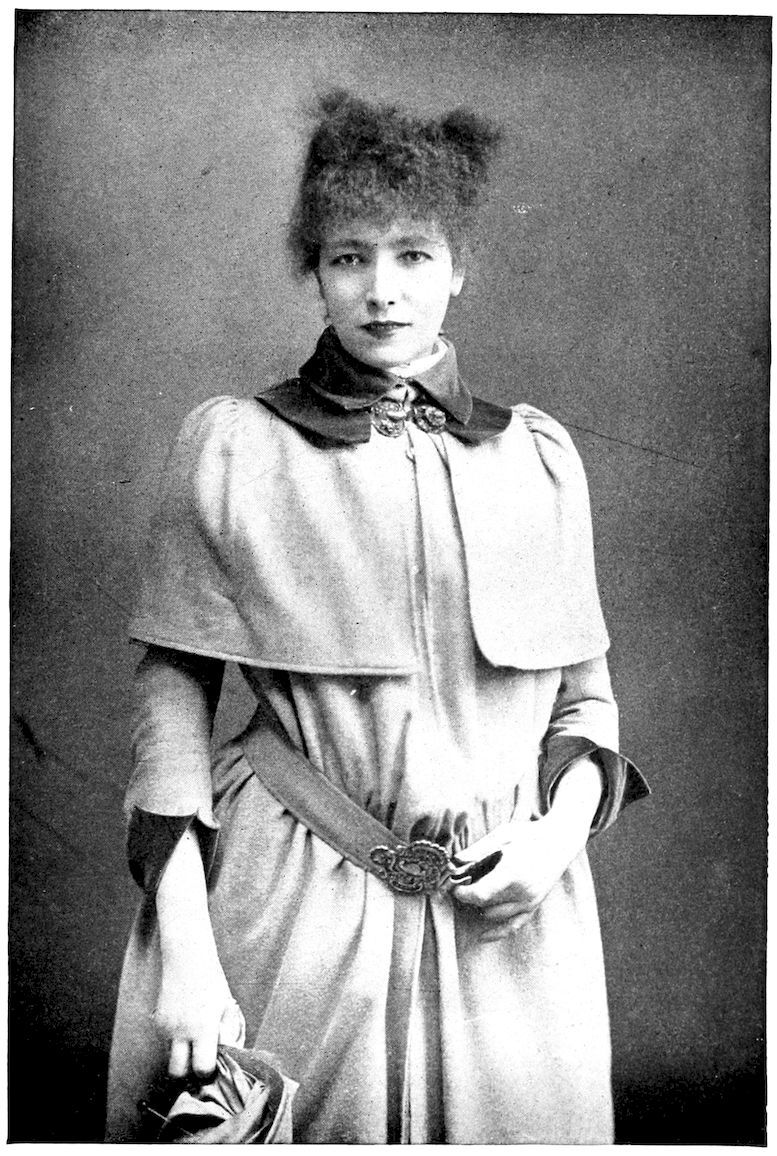

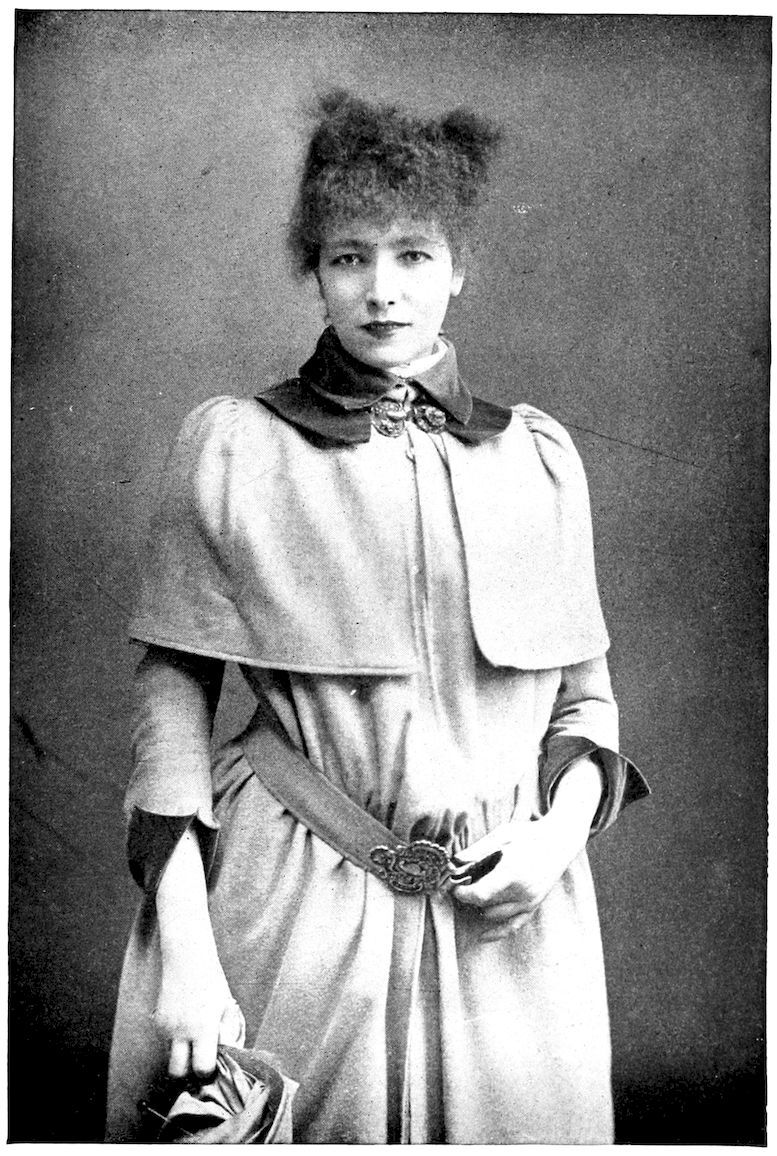

SARAH BERNHARDT IN TRAVELLING COSTUME, 1880.

I glanced in the direction of my porthole and saw a small steamer, black with people, and then two other small boats no less laden than the first one. The sun lighted up all these French flags and my heart began to beat more quickly. I had been without any news for twelve days, as, in spite of all the efforts of our good captain, L’Amérique had taken twelve days for the journey. A man had just come on deck, and I rushed toward him with outstretched hands unable to utter a single word. He gave me a packet of telegrams. I did not see anyone present, and I heard no sound. I wanted to know something. And among all the telegrams I was searching first for one, just one name. At last I had it, the telegram I had waited for, feared and hoped to receive. Here it was at last. I closed my eyes for a second, and during that time I saw all that was dear to me and felt the infinite sweetness of it all. When I opened my eyes again I was slightly embarrassed for I was surrounded by a crowd of unknown people, all of them silent and indulgent, but evidently very curious. Wishing to go away I took Mr. Jarrett’s arm and went to the salon. As soon as I entered, the first notes of the “Marseillaise” rang out, and our consul spoke a few words of welcome and handed me some flowers. A group representing the French colony presented me with a friendly address. Then M. Mercier, the editor of the Courrier des Etats-Unis, made a speech, as witty as it was kindly. It was a thoroughly French speech. Then came the terrible moment of introductions. Oh, what a tiring time that was! My mind was kept at a tension to catch the names. Mr. Pemb ... Madame Harth ... with the h aspirated. With great difficulty I grasped the first syllable, and the second finished in a confusion of muffled vowels and hissing consonants. By the time the twentieth name was pronounced I had given up listening, I simply kept on with my little risorius de Santorini, half closed my eyes, held out mechanically the arm, at the end of which was the hand that had to shake and be shaken. I replied all the time: “Combien je suis charmée, madame.... Oh, certainement!... Oh, oui!... Oh, non!... Ah!... Oh! Oh!...” I was getting dazed, idiotic—worn out with standing. I had only one idea, and that was to get my rings off the fingers that were swelling with the repeated grips they were having. My eyes were getting larger and larger with terror, as they gazed at the door through which the crowd continued to stream in my direction ... there to shake.... My risorius de Santorini must still go on working more than fifty times ... I could feel the beads of perspiration standing out under my hair—and I began to get terribly nervous. My teeth chattered and I commenced stammering. “Oh, madame!... Oh!... Je suis cha—cha....” I really could not go on any longer. I felt that I should get angry or burst out crying ... in fact that I was about to make myself ridiculous. I decided therefore to faint.... I made a movement with my hand as though it wanted to continue but could not.... I opened my mouth, closed my eyes and fell gently into Jarrett’s arms. “Quick! air!... A doctor.... Poor thing.... How pale she is! Take her hat off.... Loosen her corset.... She doesn’t wear one. Unfasten her dress....” I was terrified, but Félicie was called up in haste and my petite dame would not allow any déshabillage. The doctor came back with a bottle of ether. Félicie seized the bottle.

“Oh, no, doctor ... not ether! When madame is quite well the odor of ether will make her faint.”

This was quite true and I thought, it was time to come to my senses again. The reporters were arriving and there were more than twenty of them, but Jarrett, who was very much affected, asked them to go to the Albemarle Hotel, where I was to put up. I saw each of the reporters take Jarrett aside, and when I asked him what the secret was of all these “asides” he answered phlegmatically: “I have made an appointment with them from one o’clock. There will be a fresh one every ten minutes.” I looked at him petrified with astonishment. He met my anxious gaze and said:

“Oh, oui, il était nécessaire!”

On arriving at the Albemarle Hotel I felt tired and nervous, and wanted to be left quite alone. I hurried away at once to my room in the suite that had been engaged for me and fastened the doors. There was neither lock nor bolt on one of them, but I pushed a piece of furniture against it and then refused emphatically to open it. There were about fifty people waiting in the drawing-room, but I had that feeling of awful weariness which makes one ready to go to the most violent extremes for the sake of an hour’s repose. I wanted to lie down on the rug, cross my arms, throw my head back, and close my eyes. I did not want to talk any more, and I did not want to have to smile or look at anyone. I threw myself down on the floor and was deaf to the knocks on my door, and to Jarrett’s supplications. I did not want to argue the matter, so I did not utter a word. I heard the murmur of grumbling voices and Jarrett’s words tactfully persuading the visitors to stay. I heard the rustle of paper being pushed under the door and Mme. Guérard whispering to Jarrett, who was furious.

“You don’t know her, M. Jarrett,” I heard her say: “if she thought you were forcing the door open, against which she has pushed the furniture, she would jump out of the window!”

Then I heard Félicie talking to a French lady who was insisting on seeing me. “It is quite impossible,” she was saying. “Madame would be quite hysterical. She needs an hour’s rest and everyone must wait!” For some little time I could hear a confused murmur which seemed to get farther away, and then I fell into a delicious sleep, laughing to myself as I went off, for my good temper returned as I pictured the angry, nonplused expression on the faces of my visitors.

I woke in an hour’s time, for I have the precious gift of being able to sleep ten minutes, a quarter of an hour, or an hour, just as I like, and I then wake quite peacefully without any start, at the time I have decided upon. Nothing does me so much good as this rest to body and mind, decided upon and regulated merely by my will. Very often in my own family I have lain down on the bearskin hearth rug in front of the fire, telling everyone to go on talking and take no notice of me. I have then slept, perhaps for an hour, and on waking have found two or three newcomers in the room who, not wishing to disturb me, have taken part in the general conversation, while waiting until I should wake up to present their respects to me. Even now I lie down on the huge, wide sofa in the little Empire salon which leads into my loge and I sleep while waiting for the friends and artistes, with whom I have made appointments, to be ushered in. When I open my eyes I see the faces of my kind friends, who shake hands cordially, delighted that I should have had some rest. My mind is then tranquil and I am ready to listen to all the beautiful ideas proposed to me or to decline the absurdities submitted to me, without being ungracious.

I woke up, then, at the Albemarle Hotel an hour later and found myself lying on the rug. I opened the door of my room and discovered my dear Guérard and my faithful Félicie seated on a trunk.

“Are there any people there still?” I asked.

“Oh, madame! there are about a hundred now,” answered Félicie.

“Help me take my things off then, quickly,” I said, “and find me a white dress.”

In about five minutes I was ready, and I felt that I looked nice from head to foot. I went into the drawing-room, where all these unknown persons were waiting. Jarrett came forward to meet me, but on seeing me well dressed and with a smiling face, he postponed the sermon that he wanted to preach me.

I should like to introduce Jarrett to my readers, for he was a most extraordinary man. He was then about sixty-five or seventy years of age. He was tall with a face like King Agamemnon, framed by the most beautiful silver-white hair I have even seen on a man’s head. His eyes were of so pale a blue that when they lighted up with anger he looked as though he were blind. When he was calm and tranquil, admiring nature, his face was really handsome, but when gay and animated his upper lip showed his teeth, and curled up in a most ferocious sniff, and his grin seemed to be caused by the drawing up of his pointed ears which were always moving as though on the watch for prey. He was a terrible man, extremely intelligent, but from childhood he must have been fighting with the world, and he had the most profound contempt for all mankind. Although he must have suffered a great deal himself, he had no pity for those who suffered. He always said that every man was armed for his own defense. He pitied women, did not care for them, but was always ready to help them. He was very rich, and very economical, but not miserly. “I made my way in life,” he often said to me, “by the aid of two weapons: honesty and a revolver. In business honesty is the most terrible weapon a man can use against rascals and crafty people—the former don’t know what it is, and the latter do not believe in it—while the revolver is an admirable invention for compelling scoundrels to keep their word.” He used to tell me about wonderful and terrifying adventures. He had a deep scar under his right eye. During a violent discussion about a contract to be signed for Jenny Lind, the celebrated