CHAPTER XXIX

FROM THE GULF TO CANADA AGAIN

We arrived at Cincinnati safe and sound. We gave three performances there and set off once more for New Orleans. Now, I thought, we shall have some sunshine and we shall be able to warm our poor limbs, stiffened with three months of mortal cold. We shall be able to open our windows, and breathe fresh air instead of the suffocating and anæmia-giving steam heat. I fell asleep and dreams of warmth and sweet scents lulled me in my slumber. A knock at my door roused me suddenly, and my dog with ears erect sniffed at the door, but as he did not growl I knew it was some one of our party. I opened the door and Jarrett, followed by Abbey, made signs to me not to speak. Jarrett came in on tiptoes and closed the door again.

“Well, what is it now?” I asked.

“Why,” replied Jarrett, “the incessant rain during the last twelve days has swollen the river to such a height that the bridge across the bay of St. Louis threatens to give way. If we go back we shall require three or four days.”

I was furious. Three or four days and to go back to the snow again. Ah, no, I felt I must have sunshine!

“Why can we not pass? Oh, heavens, what shall we do!” I exclaimed.

“Well, the engine driver is here. He thinks that he might get across, but he has only just married, and he will try the crossing on condition that you give him $2,500, which he will at once send to Mobile where his father and wife live. If we get safely to the other side he will give you back this money, but if not it will belong to his family.”

“Yes, certainly, give him the money and let us cross.”

As I have said, I generally traveled by special train. This one was made up of only three carriages and the engine. I never doubted for a moment as to the success of this foolish and criminal attempt, and I did not tell anyone about it except my sister, my beloved Guérard, and my faithful Félicie and her husband Claude. The comedian, Angelo, who was sleeping in Jarrett’s berth on this journey, knew of it, but he was courageous and had faith in his star. The money was handed over to the engine driver who sent it off to Mobile. It was only just as we were actually starting that I had the vision of the responsibility I had taken upon myself, for it was risking without their consent the lives of twenty-seven persons. It was too late then to do anything, the train had started and at a terrific speed it touched the bridge. I had taken my seat on the platform and the bridge bent and swayed like a hammock under the dizzy speed of our wild course. When we were half way across it gave way so much that my sister grasped my arm and whispered: “Ah, we are drowning!” I certainly thought as she did that the supreme moment had arrived.

My last minute was not inscribed, though, for that day in the Book of Destiny. The train pulled itself together and we arrived on the other side of the water. Behind us we heard a terrible noise. The bridge had given way. For more than a week the trains from the East and the North could not enter the city.

I left the money to our brave engine driver but my conscience was by no means tranquil and for a long time my sleep was disturbed by the most frightful nightmares.

When getting out of the train I was more dead than alive. I had to submit to receiving the friendly but fatiguing deputation of my compatriots. Then, loaded with flowers, I climbed into the carriage that was to take me to the hotel. The roads were rivers and we were on an elevated spot. The lower part of the city, the coachman explained to us in Marseilles French, was inundated up to the tops of the houses. The negroes had been drowned by hundreds. “Ah, hussy!” he cried as he whipped up his horses. At that period the hotels in New Orleans were squalid—dirty, uncomfortable, black with cockroaches, and as soon as the candles were lighted, the bedrooms became filled with large mosquitoes that buzzed around and fell on one’s shoulders, sticking in one’s hair. Oh, I shudder still when I think of it!

At the same time there was an opera company in the city, the “star” of which was a charming woman, Emilie Ambre, who at one time came very near being Queen of Holland. The country was poor, like all the other American districts where the French were to be found preponderating. Ah, we are hardly good colonists!

The opera did a very poor business and we did not do excellently, either. Six performances would have been ample in that city; we gave eight.

Nevertheless, my sojourn pleased me immensely. An infinite charm was evolved from it. All these people, so different, black and white, had smiling faces. All the women were graceful. The shops were attractive from the cheerfulness of their windows. The open-air traders under the arcades challenged one another with joyful flashes of wit. The sun, however, did not show itself once. But these people had the sun within themselves.

I could not understand why boats were not used. The horses had water up to their hams, and it would have been impossible even to get into a carriage if the pavements had not been a meter or more high.

Floods being as frequent as the years, it would be of no use thinking of banking up the river or arm of the sea. But walking was made easy by the high pavements and small, movable bridges. The dark children amused themselves catching crayfish in the streams. Where did they come from? And they sold them to passersby. Now and again, we would see a whole family of water serpents speed by. They swept along with raised head and undulating body like long, starry sapphires.

I went down toward the lower part of the town. The sight was heartrending. All the cabins of the colored inhabitants had fallen into the muddy waters. They were there in hundreds squatting upon these moving wrecks, with eyes burning from fever, their white teeth chattering. Right and left, everywhere, were dead bodies floating about, knocking up against the wooden piles. Many ladies were distributing food, endeavoring to lead away the unfortunate negroes, but they refused to go. And the women would slowly shake their heads. One child of fourteen years of age had just been carried off to the hospital with his foot cut clean off at the ankle by an alligator. His family were howling with fury. They wished to keep the youngster with them. The negro quack doctor pretended that he could have cured him in two days and that the white quacks would leave him for a month in bed.

I left this city with regret, for it resembled no other city I had visited up to then. We were surprised to find that none of our party was missing though we had gone through—so they all said—various dangers. The hairdresser alone, a man called Ibé, could not recover his equilibrium, having become half mad from fear the second day of our arrival. At the theater he generally slept in the trunk in which he stored his wigs. However strange it may seem, the fact is quite true. The first night, everything passed off as usual, but during the second night he woke up the whole neighborhood by his shrieks. The unfortunate fellow had got off soundly to sleep, when he woke up with a feeling that his mattress, which hung over his collection of wigs, was being raised up by some inconceivable movements. He thought that some cat or dog had got into the trunk and he lifted up the feeble rampart. Two serpents were within, actively moving about, of a size sufficient to terrify the people that the shouts of the poor Figaro had caused to gather round.

He was still very pale when I saw him embark on board the boat that was to take us to our train. I called him and begged him to relate to me the odyssey of his terrible night. As he told me the story he showed me his heavy leg. “They were as thick as that, madame. Yes, like that....” And he quaked with fear as he recalled the dreadful girth of the reptiles. I thought that they were about one-quarter as thick as his leg, and that would have been enough to justify his fright, but the serpents in question were inoffensive water snakes that bite out of pure viciousness, but have no venom fangs.

We reached Mobile somewhat late in the day. We had stopped at that city on our way to New Orleans, and I had had a real attack of nerves caused by the “cheek” of the inhabitants who, in spite of the lateness of the hour, had got up a deputation to wait upon me. I was dead with fatigue and was dropping off to sleep in my bed on the car. I therefore energetically declined to see anybody. But these people knocked at my windows, sang about my carriage, and finally exasperated me. I quickly threw up one of the windows and emptied a jug of water on their heads. Women and men, among whom were several journalists, were splashed. Their fury was great.

I was returning to that city, preceded by the above story embellished in their favor by the drenched reporters. But on the other hand there were others who had been more courteous and had refused to go and disturb a lady at such an unearthly hour of the night. These latter were in the majority and took up my defense.

It was therefore in this warlike atmosphere that I appeared before the public of Mobile. I wanted, however, to justify the good opinion of my defenders and confound my detractors. Yes, but the Gnome who had decided otherwise was there.

Mobile was a city that was generally quite disdained by impresarii. There was only one theater. It had been let to the tragedian Barrett, who was to appear six days after me. All that remained was a miserable place, so small that I know of nothing that can be compared to it. We were playing “La Dame aux Camélias.” When Marguerite Gautier orders supper to be served, the servants who were to bring in the table ready laid tried to get it in through the door. But this was impossible. Nothing could be more comical than to see those unfortunate servants adopt every expedient.

The public laughed. Among the laughter of the spectators was one that became contagious. A negro of twelve or fifteen who had got in somehow was standing on a chair, and with his two hands holding on to his knees, his body bent, head forward, mouth open, he was laughing with such a shrill and piercing tone, and with such even continuity, that I caught it, too. I had to go out while a portion of the back scenery was being removed to allow the table to be brought in.

I returned somewhat composed, but still under the domination of suppressed laughter. We were sitting round the table and the supper was drawing to a close as usual. But just as the servants were entering to remove the table, one of them caught the scenery that had been badly adjusted by the scene shifters in their haste, and the whole back scene fell on our heads. As the scenery was nearly all made of paper in those days, it did not fall on our heads and remain there, but round our necks, and we had to remain in that position without being able to move. Our heads having gone through the paper, our appearance was most comical and ridiculous. The young negro’s laughter started again more piercing than ever, and this time my suppressed laughter ended in a crisis that left me without any strength.

The money paid for admission was returned to the public. It exceeded 15,000 francs.

This city had a fatality for me and came very near proving so during the third visit I paid to it.

That very night we left Mobile for Atlanta, where, after playing “La Dame aux Camélias,” we left again the same evening for Nashville.

We stayed for an entire day at Memphis and gave two performances. At one in the morning we left for Louisville.

We were beginning the dizzy round of the smaller towns, arriving at three, four, and sometimes six o’clock in the evening, and leaving immediately after the play. I left my car only to go to the theater and returned as soon as the play was over to retire to my elegant but diminutive bedroom. I sleep well on the railway. I felt an immense pleasure in traveling that way at high speed, sitting outside on the small platform or rather reclining in a rocking-chair, gazing on the ever-changing spectacle, that passed before me, of American plains and forests. Without stopping, we went through Louisville, Cincinnati, for the second time, Columbus, Dayton, Indianapolis, St. Joseph that has the best beer in the world, and where, we were obliged to go to an hotel on account of repairs to one of the wheels of the car. Supper was served. What a supper! Fortunately, the beer was light in both color and consistency and enabled me to swallow the dreadful things that were served up.

We left for Leavenworth, Quincy, Springfield—not the Springfield in Massachusetts—the one in Illinois.

During the journey from Springfield to Chicago, we were stopped by the snow in the middle of the night. The sharp and deep groanings of the locomotive had already awakened me. I summoned my faithful Claude and learned that we were to stop and wait for help. Aided by my Félicie, I dressed in haste and tried to descend, but it was impossible. The snow was as high as the platform of the car. I remained wrapped up in furs, contemplating the magnificent night. The sky was hard, implacable, without a star, but all the same translucent. Lights extended as far as the eye could see along the rails before me, for I had taken refuge on the rear platform. These lights were to warn the trains that followed. Four of them came up and stopped when the first fog-signals went off beneath their wheels, then crept slowly forward to the first light where a man who was stationed there explained the incident. The same lights were lit immediately for the following train, as far off as possible, and a man proceeding beyond the lights placed detonators on the rails. Each train that arrived followed that course.

We were blocked by the snow. The idea came to me of lighting the kitchen fire and I thus got enough boiling water to melt the top coating of snow on the side where I wanted to get down. Having done this, Claude and the negroes got down and cleared away a small portion as well as they could. I was at last able to get down myself and tried to remove the snow to one side. My sister and I finished by throwing snowballs at each other and the mêlée became general. Abbey, Jarrett, the secretary, and several of the artistes joined in and we were warmed up through this small battle with white cannon balls.

When dawn appeared we were to be seen firing a revolver and Colt rifle at a target made from a champagne case. A distant sound, deadened by the cotton wool of the snow, at length made us realize that help was approaching. As a matter of fact, two engines with men who had shovels, hooks, and spades, were coming at full speed from the opposite direction. They were obliged to slow down on getting to one kilometer of where we were, and the men got down, clearing the way before them. They finally succeeded in reaching us, but we were obliged to go back and take the western route. The unfortunate artistes who had counted on getting breakfast in Chicago, which we ought to have reached at eleven o’clock, were lamenting, for with the new itinerary that we were forced to follow, it would be half past one before we could get to Milwaukee, where we were to give a matinée at two o’clock—“La Dame aux Camélias.” I therefore had the best lunch I could prepared and my negroes carried it to my company, the members of which showed themselves very grateful.

The performance did not begin till three and finished at half past six o’clock; we started again at eight with “Froufrou.”

Immediately after the play was over we left for Grand Rapids, Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburg, in which latter city I was to meet an American friend of mine who was to help me to realize one of my dreams—at least I fancied so. In partnership with his brother, my friend was the owner of a large steel works and several petroleum wells. I had known him in Paris, and had met him again at New York, where he offered to conduct me to Buffalo so that I could visit, or rather where he could show me, the Falls of Niagara, for which he entertained a lover’s passion. Frequently, he would start off quite unexpectedly, like a madman, and take a rest at a place just near the Niagara Falls. The deafening sound of the cataracts seemed like music after the hard, hammering, strident noise of the forges at work on the iron, and the limpidity of the silvery cascades rested his eyes and refreshed his lungs, saturated as they were with petroleum and smoke.

My friend’s buggy, drawn by two magnificent horses, took us along in a bewildering whirlwind of mud splashing over us and snow blinding us. It had been raining for a week and Pittsburg in 1881 was not what it is at present, although it was a city which impressed one on account of its commercial genius. The black mud ran along the streets and everywhere in the sky rose huge patches of thick, black, opaque smoke; but there was a certain grandeur about it all, for work was king there. Trains ran through the streets laden with barrels of petroleum or piled as high as possible with charcoal and coal. That fine river, the Ohio, carried along with it steamers, barges, and loads of timber fastened together and forming enormous rafts which floated down the river alone to be stopped on the way by the owner for whom they were destined. The timber is marked and no one else thinks of taking it. I am told that the wood is not conveyed in this way now and it is a pity.

The carriage took us along through streets and squares in the midst of railways, under the enervating vibration of the electric wires which ran like furrows across the sky. We crossed a bridge which shook under the light weight of the buggy. It was a suspension bridge. Finally, we drew up at my friend’s home. He introduced his brother to me, a charming man but very cold and correct, and so quiet that I was astonished.

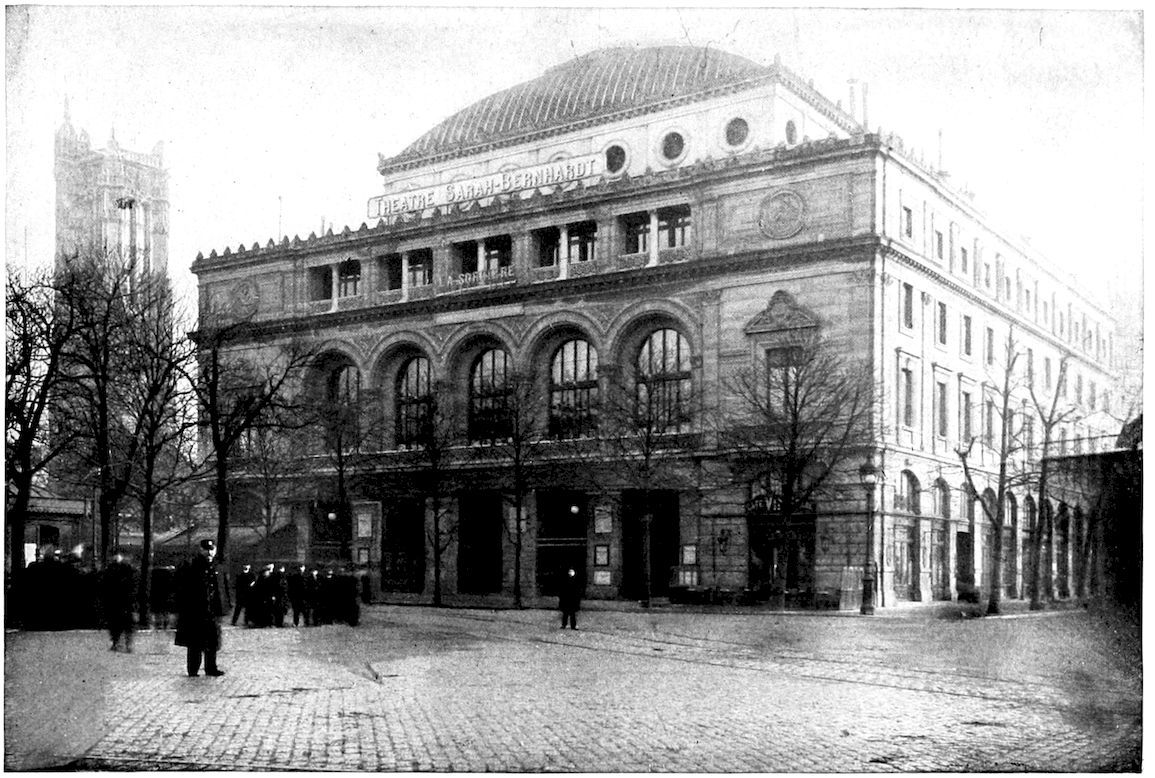

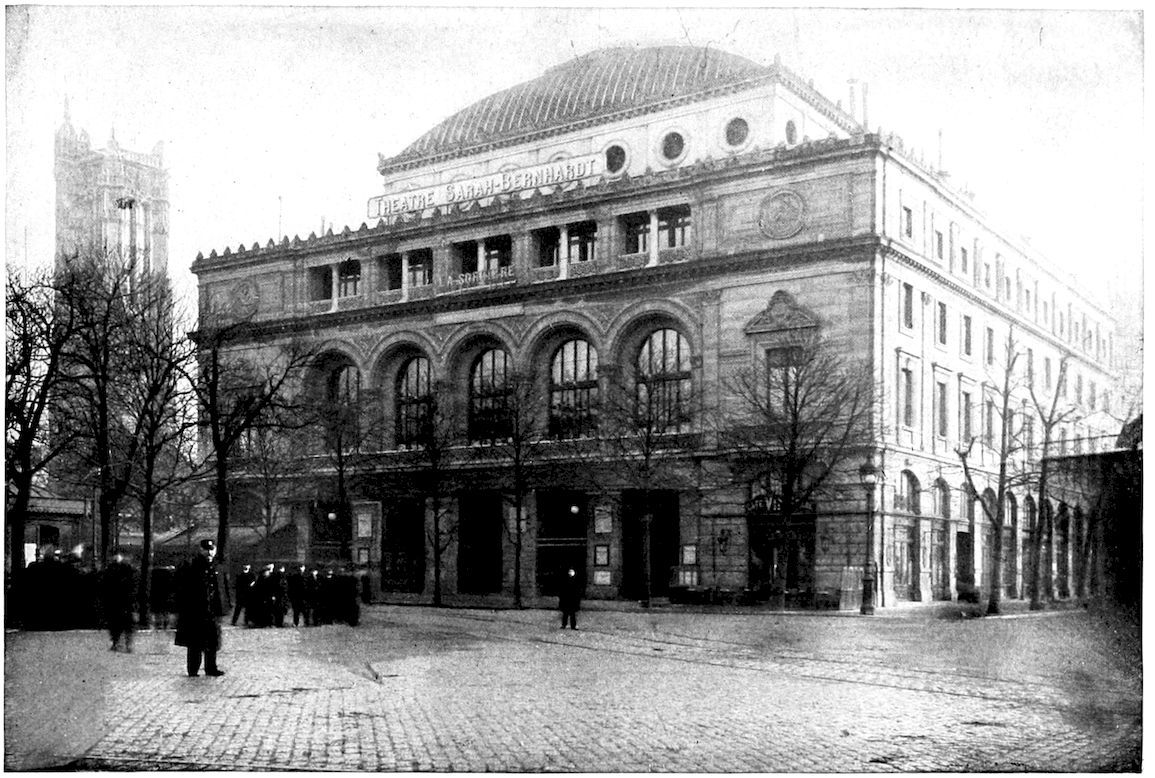

THÉÂTRE SARAH BERNHARDT, PARIS.

“My poor brother is deaf,” said my companion, after I had been exerting myself for five minutes to talk to him in my gentlest voice. I looked at this poor millionaire who was living in the most extraordinary noise and who could not even hear the faintest echo of the outrageous uproar. He could not hear anything at all, and I wondered whether he was to be envied or pitied. I was then taken to visit his incandescent ovens and his vats in a state of ebullition. I went into a room where some steel disks were cooling, which looked like so many setting suns. The heat from them seemed to scorch my lungs, and I felt as though my hair would take fire. We then went down a long, narrow street through which small trains were running to and fro. Some of those trains were laden with incandescent metals which irised the air as they passed. We walked in single file along the narrow passage reserved for foot passengers between the rails. I did not feel at all safe and my heart began to beat fast. Blown each way by the wind from the two trains coming in opposite directions and passing each other, I drew my skirts closely round me so that they should not be caught. Perched on my high heels, at every step I took I was afraid of slipping on this narrow, greasy, coal-strewn pavement. To sum up briefly, it was a very unpleasant moment, and very delighted I was to come to the end of that interminable street which led to an enormous field stretching away as far as the eye could see. There were rails lying all about here which men were polishing and filing, etc. I had had quite enough, though, and I asked to be allowed to go back and rest. So we all three returned to the house.

On arriving there, valets arrayed in livery opened the doors, took our furs, walking on tiptoes as they moved about. There was silence everywhere and I wondered why, as it seemed to me incomprehensible. My friend’s brother scarcely spoke at all and when he did his voice was so low that I had great difficulty in understanding him. When we asked him any question by gesticulating, and we had to listen most attentively to catch his reply, I noticed that an almost imperceptible smile lighted up for an instant his stony face. I understood very soon that this man hated humanity and that he avenged himself in his own way for his infirmity.

Lunch had been prepared for us in the winter conservatory, a nook of magnificent verdure and flowers. We had not taken our seats at the table when the songs of a thousand birds burst forth like a veritable fanfare. Underneath some large leaves whole families of canaries were imprisoned by invisible nets. They were everywhere, up in the air, down below, under my chair, on the table behind me, all over the place. I tried to quiet this shrill uproar by shaking my napkin and speaking in a loud voice, but the little feathered tribe began to sing in a maddening way. The deaf man was leaning back in a rocking-chair and I noticed that his face had lighted up. He laughed aloud in an evil, spiteful manner. Just as my own temper was getting the better of me, a feeling of pity and indulgence came into my heart for this man whose vengeance seemed to me as pathetic as it was puerile. Promptly deciding to make the best of my host’s spitefulness, and assisted by his brother, I took my tea into the hall at the other end of the conservatory. I was nearly dead with fatigue and when my friend proposed that I should go with him to see his petroleum wells, a few miles out of the city, I gazed at him with such a scared, hopeless expression that he begged me in the most friendly and polite way to forgive him.

It was five o’clock and quite dusk, and I wanted to go back to my hotel. Mr. Th—— asked if I would allow him to take me back by the hills. The road was rather longer, but I should be able to have a bird’s-eye view of Pittsburg, and he assured me that it was quite worth while. We started off in the buggy with two fresh horses and a few minutes later I had the wildest dream. It seemed to me that he was Pluto, the god of the infernal regions, and I was Proserpine. We were traveling through our empire at a quick trot, drawn by our winged horses. All around us we could see fire and flames. The blood-red sky was burning with long, black trails that looked like widows’ veils. The ground was covered with long arms of iron stretched heavenward in a supreme imprecation. These arms threw forth smoke, flames, or sparks which fell again in a shower of stars. The carriage carried us on up the hills, and the cold froze our limbs, while the fires excited our brain. It was then that my friend told me of his love for the Niagara Falls. He spoke of them more like a lover than an admirer, and told me he liked to go to them alone. He said, though, that for me he would make an exception. He spoke of the rapids with such intense passion that I felt rather uneasy and began to wonder whether the man was not mad. I grew alarmed, for he was driving along over the very tops of the hills, jumping the stone heaps. I glanced at him sideways; his face was calm, but his underlip twitched slightly, and I had noticed this peculiarity with his deaf brother, too. By this time I was quite nervous. The cold and the fires, this demoniacal drive, the sound of the anvil ringing out mournful chimes which seemed to come from under the earth, and then the deep forge whistle sounding like a desperate cry rending the silence of the night; the chimney stacks, too, with their worn-out lungs spitting forth their smoke with a perpetual death rattle, and the wind which had just risen twisting the streaks of smoke into spirals which it sent up toward the sky or beat down all at once on to us—altogether this wild dance, of the natural and the combined elements, affected my whole nervous system so that it was quite time for me to get back to the hotel. I sprang out of the carriage quickly on arriving and arranged to see my friend at Buffalo, but, alas! I was never to see him again. He took cold that very day and could not meet me there, and the following year I heard that he had been dashed against the rocks when trying to boat in the rapids. He died of his passion, for his passion.

At the hotel all the artistes were awaiting me, as I had forgotten we were to have a rehearsal of “La Princesse Georges” at half past four. I noticed a face that was unknown to me among the members of the company, and on making inquiries about this person found that he was an illustrator who had brought an introduction from Jarrett. He asked to be allowed to make a few sketches of me, and after giving orders that he should be taken to a seat, I did not trouble any more about him. We had to hurry through the rehearsal in order to be at the theater in time for the performance of “Froufrou,” which we were giving that night. The rehearsal was accordingly rushed and gabbled through so that it was soon over, and the stranger took his departure, refusing to let me look at his sketches on the plea that he wanted to do them up before showing them. My joy was great the following day when Jarrett arrived at my hotel perfectly furious, holding in his hand the principal newspaper of Pittsburg in which our illustrator, who turned out to be a journalist, had written an article giving at full length an account of the dress rehearsal of “Froufrou.” “In the play of ‘Froufrou,’” wrote this delightful imbecile, “there is only one scene of any importance and that is the one between the two sisters. Mme. Sarah Bernhardt did not impress me greatly and, as to the artistes of the Comédie Française, I considered they were mediocre. The costumes were not very fine, and in the ball scene the men did not wear dress suits.”

Jarrett was wild with rage, and I was wild with joy. He knew my horror of reporters and he had introduced this one in an underhand way, hoping to get a good advertisement out of it. The journalist imagined that we were having a dress rehearsal of “Froufrou,” and we were merely rehearsing Alexandre Dumas’ “Princesse Georges” for the sake of refreshing our memories. He had mistaken the scene between the Princesse Georges and the Comtesse de Terremonde for the scene in the third act between the two sisters in “Froufrou.” We were all of us wearing our traveling costumes and he was surprised at not seeing the men in dress coats and the women in evening dress. What fun this was for our company, and for all the town, and I may add, what a subject it furnished for the jokes of all the rival newspapers!