CHAPTER XXVIII

MY TOUR OF THE WESTERN STATES

After our immense and noisy success at Montreal, we were somewhat surprised with the icy welcome of the public at Springfield.

We played “La Dame aux Camélias,” in America “Camille”—why? No one was ever able to tell me. This play, that the public rushed to see in crowds, shocked the overstrained Puritanism of the small American states. The critics of the large cities discussed this modern Magdalene. But those of the small towns began by throwing stones at her. This stilted reserve on the part of the public, prejudiced against the impurity of Marguerite Gautier, we met with from time to time in the small cities. Springfield at that time had barely thirty thousand inhabitants.

During the day I passed at Springfield I called at a gunsmiths to purchase a Colt gun. The salesman showed me into a long and very narrow courtyard where I tried several guns. On turning round, I was surprised and confused to see two gentlemen taking an interest in my shooting. I wished to withdraw at once, but one of them came up to me—“Would you like, madam, to come and fire off a cannon?” I almost fell to the ground with surprise, and did not reply for a second. Then I said, “Yes, I would.”

An appointment was made with my strange questioner, who was the director of the Colt gun factory. An hour afterwards I went to the rendezvous.

More than thirty people were there already who had been hastily invited. It got on my nerves a trifle. I fired off the newly invented quick-firing cannon. It amused me very much without procuring me any emotion, and that evening, after the icy performance, we left for Baltimore with a vertiginous rush, the play having finished later than the hour fixed for the departure of the train. It was necessary to catch it at any cost. The three enormous carriages that made up my special train went off under full steam. Having two engines we bounded over the rails but stayed on, thanks to some miracle.

We finally succeeded in catching up with the express that (having been warned by telegram) knew we were on its track; it made a short stop—just long enough to couple us to it—and in that way we reached Baltimore, where I stayed four days and gave five performances.

Two things struck me in that city—the deadly cold in the hotels and the theater, and the loveliness of the women. I felt a profound sadness at Baltimore for it was the first time I had spent the first of January far from everything that was dear to me. I wept all night and underwent that moment of discouragement that makes one wish for death.

The success, however, had been colossal in that charming city, which I left with regret to go to Philadelphia, where we were to remain a week.

That handsome city I do not care for. I received an enthusiastic welcome there in spite of a change of programme the first evening. Two artistes having missed the train we could not play “Adrienne Lecouvreur” and I had to replace it by “Phèdre,” the only piece in which the absentees could be replaced. The receipts averaged 20,000 francs for the seven performances given in six days. My sojourn was saddened by a letter announcing the death of my friend Gustave Flaubert, the writer who had the beauty of our language most at heart.

From Philadelphia we proceeded to Chicago.

At the station I was received by a deputation of Chicago ladies, and a bouquet of rare flowers was handed to me by a delightful young lady, Madam Lily ——. Jarrett then led me into one of the rooms of the station where the French delegates were waiting.

A very short but highly emotional speech from our consul spread confidence and friendly feelings among all, and after having returned heartfelt thanks, I was preparing to leave the station, when I remained stupefied—and it seems that my features assumed such an intense expression of suffering that everybody ran toward me to offer assistance. For a sudden anger electrified all my being, and I walked straight toward the horrible vision that had just appeared before me—the whale man! He was alive, that horrible Smith—enveloped in furs, with diamonds on all of his fingers. He was there with a bouquet in his hand, the horrible brute! I refused the flowers and repulsed him with all my strength increased tenfold by anger, and a flood of confused words escaped my pallid lips. But this scene charmed him, for it was repeated and spread about, magnified, and the whale had more visitors than ever.

I went to the Palmer House, one of the most magnificent hotels of that day, whose proprietor, Mr. Palmer, was a perfect gentleman, courteous, kind, and generous, for he filled the immense apartment I occupied with the rarest flowers, and taxed his ingenuity in order to have me served in the French style, a rare thing at that time.

We were to remain a fortnight in Chicago. Our success exceeded all expectations. This fortnight at Chicago seemed to me the most agreeable days I had had since my arrival in America. First of all there was the vitality of the city in which men pass each other without ever stopping, with knitted brows, with one thought in mind, “the end to attain.” They move on and on, never turning for a cry or prudent warning. What takes place behind them, matters little. They do not wish to know why a cry was raised; and they have no time to be prudent, “the end to attain” awaits them.

Women here, as everywhere else in America, do not work, but they do not stroll about the streets as in other cities; they walk quickly; they also are in a hurry to seek amusement. During the daytime I went some distance into the surrounding country in order not to meet the sandwich men advertising the whale.

One day I went to the pig-slaughtering house. Ah, what a dreadful and magnificent sight! There were three of us—my sister, myself, and an Englishman, a friend of mine. On arrival, we saw hundreds of pigs hurrying, bunched together, grunting and snorting, file off along a small, narrow, raised bridge.

Our carriage passed under this bridge and stopped before a group of men who were waiting for us. The manager of the stockyards received us and led the way to the special slaughterhouses. On entering into the immense shed, which was dimly lighted by windows with greasy and ruddy panes, an abominable smell gets into one’s throat, a smell that only leaves one several days afterwards. A sanguinary mist rises everywhere like a light cloud floating on the side of a mountain and lit up by the setting sun. An infernal hubbub drums itself into one’s brain; the almost human cries of the pigs being slaughtered, the violent strokes of the hatchets, lopping off the limbs, the successive “Han!” of the “ripper” who, with a superbly sweeping gesture lifts the heavy hatchet, and with one stroke opens from top to bottom the unfortunate, quivering animal hung on a hook. During the terror of the moment, one hears the continuous grating of the revolving razor, which, in one second, removes the bristles from the trunk thrown to it by the machine that has cut off the four legs. The whistle by which escapes the steam from the hot water in which the head of the animal is scalded; the rippling of the water that is constantly renewed; the cascade of the waste water; the rumbling of the small trains carrying under wide arches trucks loaded with hams, sausages, etc. ... all that sustained by the sounds of the bells of the engines warning of the danger of their approach, and which in this spot of terrible massacre seem to be the perpetual knell of wretched agonies. Nothing was more Hoffmanesque than this slaughter of pigs at the period I am speaking about, for since then, a sentiment of humanity has crept, although still somewhat timidly, into this temple of porcine hecatombs.

I returned from this visit quite ill. That evening I played in “Phèdre.” I went on to the stage quite unnerved and trying to do everything to get rid of the horrible vision of a little while ago. I threw myself heart and brain into my rôle, so much so that at the end of the fourth act I absolutely fainted on the stage.

On the day of my last performance, a magnificent collar of camellias in diamonds was handed me on behalf of the ladies of Chicago. I left that city fond of everything in it—its people, its lake as big as a small inland sea, its audiences who were so enthusiastic, everything, everything, but its stockyards.

I did not even bear any ill-will toward the bishop who also, as had happened in other cities, had denounced my art and French literature. By the violence of his sermons he had as a matter of fact advertised us so well that Mr. Abbey, the manager, wrote the following letter to him:

HIS GRACE: Whenever I visit your city I am accustomed to spend $400 in advertising. But as you have done the advertising for me, I send you $200 for your poor.

HENRY ABBEY.

We left Chicago to go to St. Louis, where we arrived after having covered two hundred and eighty-three miles in fourteen hours.

In the drawing-room of my car, Abbey and Jarrett showed me the statement of the sixty-two performances that had been given since our departure; the gross receipts were $227,459, that is to say 1,137,295 francs—an average of 18,343 francs per performance. This gave me great pleasure on Henry Abbey’s account, who had lost everything in his previous tour with an admirable troupe of Opera artistes, and greater pleasure still on my own account, for I was to receive a good share of the receipts.

We stayed at St. Louis all the week from the 24th to the 31st of January. I must admit that this city, which was specially French, was less to my liking than the other American cities, as it was dirty and the hotels were not very comfortable. Since then St. Louis has made great strides, but it was the Germans who planted there the bulb of progress. At the time of which I speak, the year 1881, the city was repulsively dirty. In those days, alas! we were not great at colonizing, and all the cities where French influence preponderated, were poor and behind the times. I was bored to death at St. Louis, and I wanted to leave the place at once, after paying the indemnity to the manager, but Jarrett, the upright man, the stern man of duty, the ferocious man, said to me, holding the contract in his hand: “No, madame, you must stay; you can die of ennui here, if you like, but stay you must.”

By way of entertaining me, he took me to a celebrated grotto, where we were to see some millions of fish without eyes. The light had never penetrated into this grotto, and as the first fish who lived there had no use for their eyes, their descendants had no eyes at all. We went down and groped our way to the grotto, very cautiously, on all fours like cats. The road seemed to me interminable; but, at last, the guide told us that we had arrived at our destination. We were able to stand upright again, as the grotto itself was higher. I could see nothing, but I heard a match being struck, and the guide then lighted a small lantern. Just in front of me, nearly at my feet, was a rather deep natural basin: “You see,” remarked our guide phlegmatically, “that is the pond, but just at present there is no water in it, neither are there any fish; you must come again in three months’ time.”

Jarrett made such a fearful grimace that I was seized with an uncontrollable fit of laughter, of that kind of laughter which borders on madness; I was suffocated with it, and I hiccoughed and laughed till the tears came. I then went down into the basin of the pond in search of a relic of some kind, a little skeleton of a dead fish, or anything, no matter what. There was nothing to be found, though, absolutely nothing. We had to return on all fours as we came. I made Jarrett go first, and the sight of his big back in his fur coat as he walked along on hands and feet, grumbling and swearing as he went, gave me such delight that I no longer regretted anything, and I gave ten dollars to the guide to his ineffable surprise.

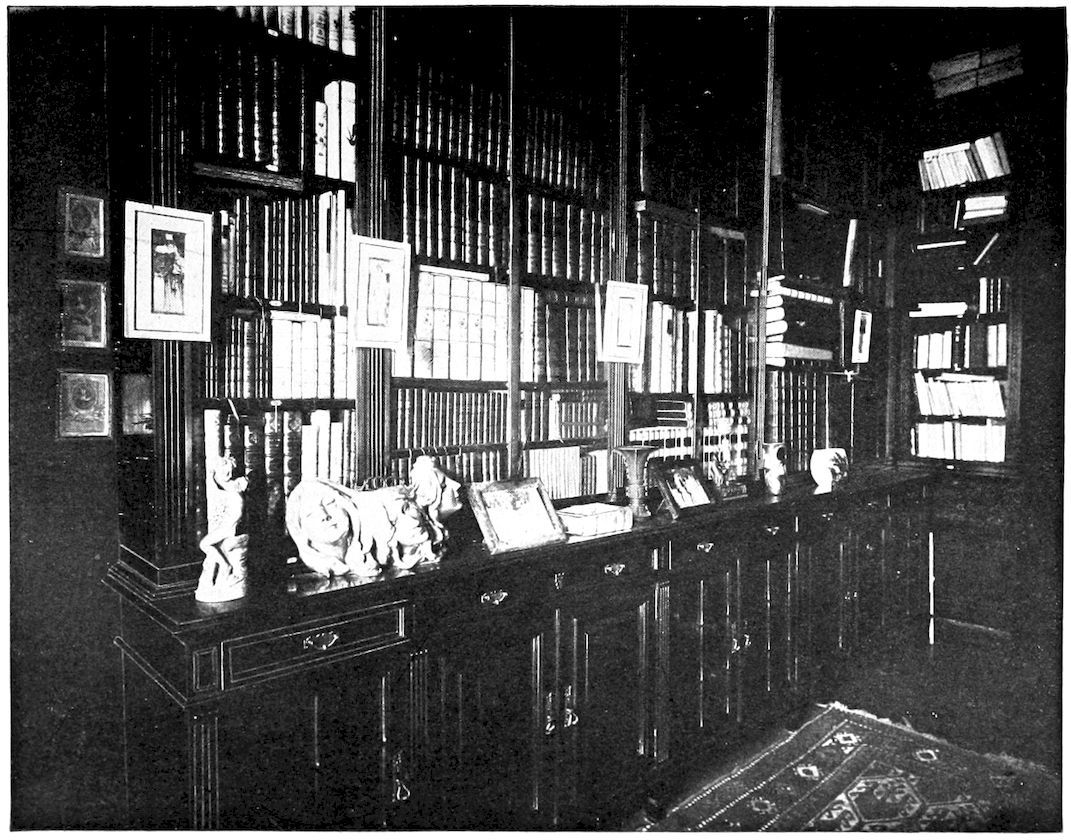

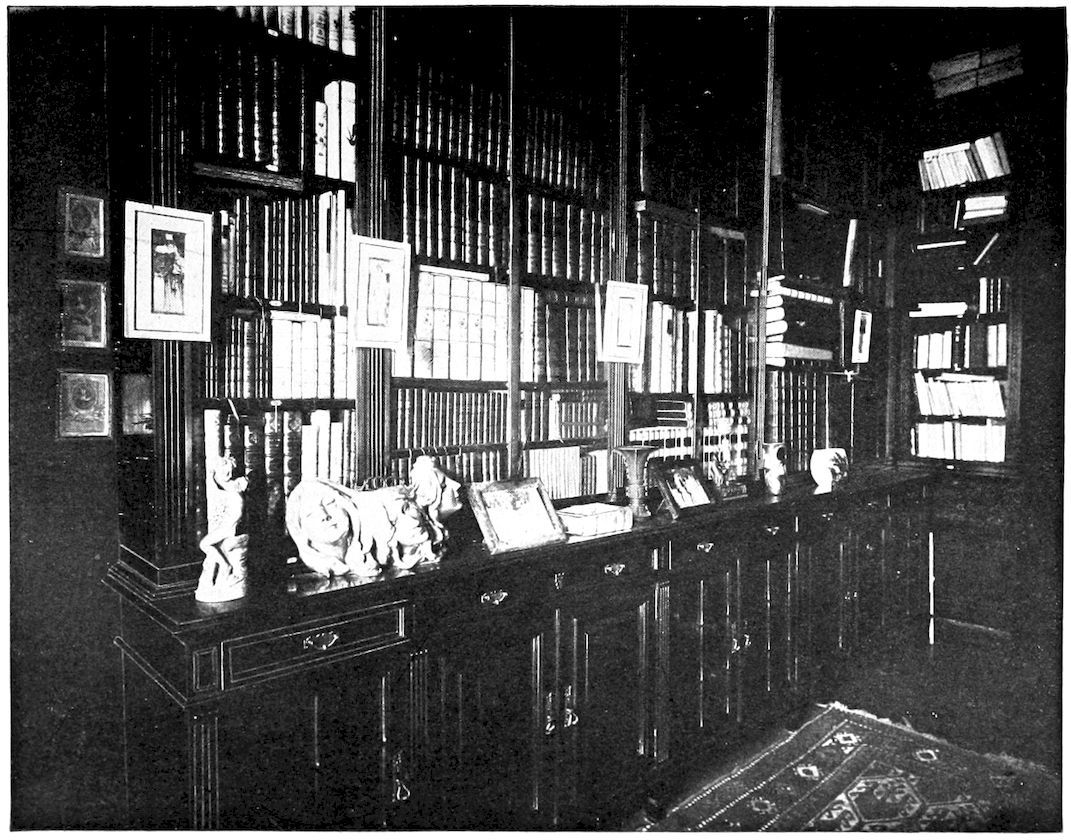

LIBRARY IN MADAME BERNHARDT’S HOUSE, PARIS.

We returned to the hotel, and I was informed that a jeweler had been waiting for me more than two hours. “A jeweler!” I exclaimed; “but I have no intention of buying any jewelry; I have too much as it is.” Jarrett, however, winked at Abbey, who was there as we entered. I saw at once that there was some understanding between the jeweler and my two impresarii. I was told that my ornaments needed cleaning, that the jeweler would undertake to make them look like new, repair them if they required it and, in a word ... exhibit them. I rebelled, but it was of no use. Jarrett assured me that the ladies of St. Louis were particularly fond of shows of this kind. He said it would be an excellent advertisement, that my jewelry was very much tarnished, that several stones were missing, and that this man would replace them for nothing. “What a saving,” he added; “just think of it!”

I gave up, for discussions of that kind bore me to death, and two days later the ladies of St. Louis went to admire my ornaments in this jeweler’s showcases under a blaze of light. Poor Mme. Guérard, who also wanted to see them, came back horrified:

“They have added to your things,” she said, “sixteen pairs of earrings, two necklaces, and thirty rings; a lorgnette all diamonds and rubies, a gold cigarette holder set with turquoises, a small pipe, the amber mouthpiece of which is encircled with diamond stars, sixteen bracelets, a toothpick studded with sapphires, and a pair of spectacles with gold mounts ending with small acorns of pearls.”

“They must have been made specially,” said poor Guérard, “for there can’t be anyone who would wear such glasses, and on them were written the words: ‘Spectacles which Madame Sarah Bernhardt wears when she is at home.’” I certainly thought that this was exceeding all the limits allowed to advertisement. To make me smoke pipes and wear spectacles was going rather too far, and I got into my carriage and drove at once to the jeweler’s. I arrived just in time to find the place closed. It was five o’clock on Saturday afternoon, the lights were out, and everything was dark and silent. I returned to the hotel and spoke to Jarrett of my annoyance: “What does it all matter, madame?” he said tranquilly; “so many girls wear spectacles, and as to the pipe, the jeweler tells me he has received five orders from it, and that it is going to be quite the fashion. Anyhow, it is of no use worrying about the matter, as the exhibition is now over, your jewelry will be returned to-night, and we leave here the day after to-morrow.” That evening the jeweler returned all the objects I had lent him, and they had been polished and repaired, so that they looked quite new. He had included with them a gold cigarette holder set with turquoises, the very one that had been on view. I simply could not make that man understand anything, and my anger cooled down when confronted by his pleasant manner and his joy.

This advertisement, though, came very near costing my life. Tempted by the thought of this huge quantity of jewelry, the greater part of which did not belong to me, a little band of sharpers planned to rob me, believing that they would find all these valuables in the large handbag which my steward always carried.

On Sunday, the 30th of January, we left St. Louis at eight o’clock in the morning for Cincinnati. I was in my magnificently appointed Pullman car, and I had requested that my car should be put at the end of our special train, so that from the platform I might enjoy the beauty of the landscape which passes before one like a continually changing living panorama.

We had scarcely been more than ten minutes en route when the guard suddenly stooped down and looked over the little balcony. He then drew back quickly, and his face turned pale. Seizing my hand, he said in a very anxious tone, in English, “Please go inside, madame.” I understood that we were in danger of some kind. He pulled the alarm signal, made a sign to another guard, and, before the train had quite come to a standstill, the two men sprang down and disappeared under the train. The guard had fired a revolver in order to attract everyone’s attention, and Jarrett, Abbey, and the artistes hurried out into the narrow corridor. I found myself in the midst of them, and to our stupefaction, we saw the two guards dragging out from underneath my compartment a man armed to the teeth. With a revolver held to his temple on either side he decided to confess the truth of the matter. The jeweler’s exhibition had excited the envy of all the tribes of thieves, and this man had been despatched by an organized hand at St. Louis to relieve me of my jewelry. He was to unhook my carriage from the rest of the train between St. Louis and Cincinnati, at a certain spot known as the “Little Incline.” As this was to be done during the night, and my carriage was the last, the thing was comparatively easy, as it was only a question of lifting the enormous hook and drawing it out of the link. The man was a veritable giant and he was fastened on to my carriage. We examined his apparatus and found that it consisted of merely very thick, wide straps of leather, about half a yard wide. By means of these, he was fastened firmly to the under part of the train with his hands perfectly free. The courage and the sang froid of that man were admirable. He told us that seven armed men were waiting for us at the “Little Incline” and that they certainly would not have injured us if we had not attempted to resist, for all they wanted was my jewelry, and the money which the secretary carried, $2,300. Oh! he knew everything, he knew everyone’s name, and he gabbled on in bad French: “Oh! as for you, madame, we should not have done you any harm in spite of your pretty little revolver; we should even have let you keep it.”

And so this man and his band knew that the secretary slept at my end of the train and that he was not to be dreaded much, poor Chatterton, that he had with him $2,300, and that I had a very prettily chased revolver, ornamented with cats’ eyes. The man was firmly bound and taken in charge by the two guards, and the train was then backed to St. Louis—we had started away only a quarter of an hour before. The police were informed and they sent us five detectives. A goods train, which should have gone on half an hour after us, was sent on ahead. Eight detectives traveled on this goods train and received orders to get out at the “Little Incline.” Our giant was handed over to the police authorities, but I was promised that he should be dealt with mercifully on account of the confession he had made. Later on, I learned that this promise had been kept, as the man was sent back to his native country, Ireland.

From this time forth, my compartment was always placed between two others every night. In the daytime I was allowed to have my carriage at the end on condition that I would agree to have an armed detective on my bridge, whom I was to pay, by the way, for his services. We started about twenty-five minutes after the goods train. All the men were requested to have their revolvers in readiness and some white sticks like pastry rollers were given to the women and to the men who had not any revolvers. Our dinner was very gay and everyone was rather excited. As to the guard who had discovered the giant hidden under the train, Abbey and I had rewarded him so lavishly that he was intoxicated, and kept coming on every occasion to kiss my hand and weep his drunkard’s tears, repeating all the time: “I saved the French lady, I’m a gentleman.”

When, finally, we approached the “Little Incline,” it was dark. The engine driver wanted to rush along at full speed, but we had not gone five miles when petards exploded under the wheels, and we were obliged to slacken our pace. We wondered what new danger there was awaiting us, and we began to feel anxious. The women were nervous and some of them were in tears. We went along slowly, peering into the darkness, trying to make out the form of a man or of several men by the light of each petard. Abbey suggested going at full speed, because these petards had been placed along the line by the bandits, who had probably thought of some way of stopping the train in case their giant did not succeed in unhooking the carriage. The engine driver refused to go more quickly, declaring that these petards were the signals placed there by the railway company, and that he could not risk everyone’s life on a mere supposition. The man was quite right and he was certainly very brave.

“We can certainly settle a handful of ruffians,” he said, “but I could not answer for anyone’s life if the train went off the lines, or collided with something, or went over a precipice.”

We continued, therefore, to go slowly. The lights had been turned off in the car, so that we might see as much as possible without being seen ourselves. We had tried to keep the truth from the artistes, except from three men whom I had sent for to come to my carriage. The artistes really had nothing to fear from the robbers, as I was the only person at whom they were aiming. To avoid all unnecessary questions and evasive answers we sent the secretary to tell them that as there was some obstruction on the line the train had to go slowly. They were also told that one of the gas pipes had to be repaired before we could have the light again. The communication was then cut between my car and the rest of the train. We had been going along like this for ten minutes, perhaps, when everything was suddenly lighted up by a fire, and we saw a gang of railway men hastening toward us. It makes me shudder now when I think how nearly these poor fellows were to being killed. Our nerves had been in such a state of tension for several hours that we imagined at first that these men were the wretched friends of the giant. Some one fired at them, and if it had not been for our plucky engine driver calling out to them to stop, with the addition of a terrible oath, two or three of these poor men would have been wounded. I, too, had seized my revolver, but before I could have drawn out the ramrod which serves as a cog to prevent it from going off, anyone would have had time to seize me, bind me, and kill me a hundred times over. And still any time I go to a place where I think there is danger, I invariably take my pistol with me, for it is a pistol and not a revolver. I always call it a revolver, but, in reality, it is a pistol, and of a very old-fashioned make, too, with this ramrod and the trigger so hard to pull that I have to use my other hand as well. I am not a bad shot, for a woman, provided that I may take my time, but this is not very easy when one wants to fire at a robber. And yet, I always have my pistol with me; it is here on my table and I can see it as I write. It is in its case, which is rather too narrow, so that it requires a certain amount of strength and patience to pull it out. If an assassin should arrive at this particular moment I should first have to unfasten the case, which is no easy matter, then to get the pistol out, pull out the ramrod, which is rather too firm, and press the trigger with both hands. And yet, in spite of all this, the human animal is so strange that this little ridiculously useless object here before me seems to me an admirable protection. And nervous and timid as I am, alas! I feel quite safe when I am near to this little friend of mine, who must roar with laughter inside the little case out of which I can scarcely drag it.

Well, everything was now explained to us. The goods train which had started before us ran off the line, but no great damage was done, and no one was killed. The St. Louis band of robbers had arranged everything, and had prepared to have this little accident two miles from the “Little Incline,” in case their comrade, crouching under my car, had not been able to unhook it. The train left the rails, but when the wretches rushed forward believing that it was mine, they found themselves surrounded by the band of detectives. It seems that they fought like demons. One of them was killed on the spot, two more wounded, and all the others taken prisoners. A few days later the chief of this little band was hanged. He was a Belgian, named Albert Wirbyn, twenty-five years of age.

I did all in my power to save him, for it seemed to me that unintentionally I had been the instigator of his evil plan. If Abbey and Jarrett had not been so rabid for advertisement, if they had not added more than 600,000 francs’ worth of jewelry to mine, this man, this wretched youth, would not perhaps have had the stupid idea of robbing me.

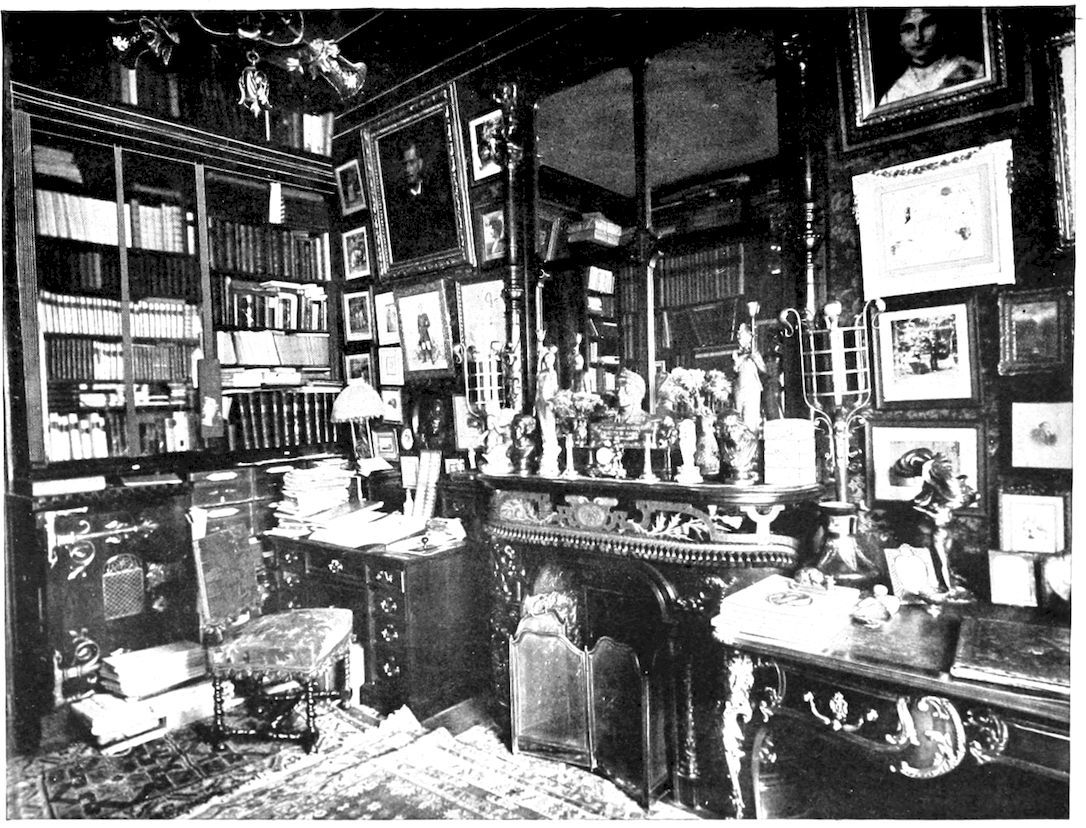

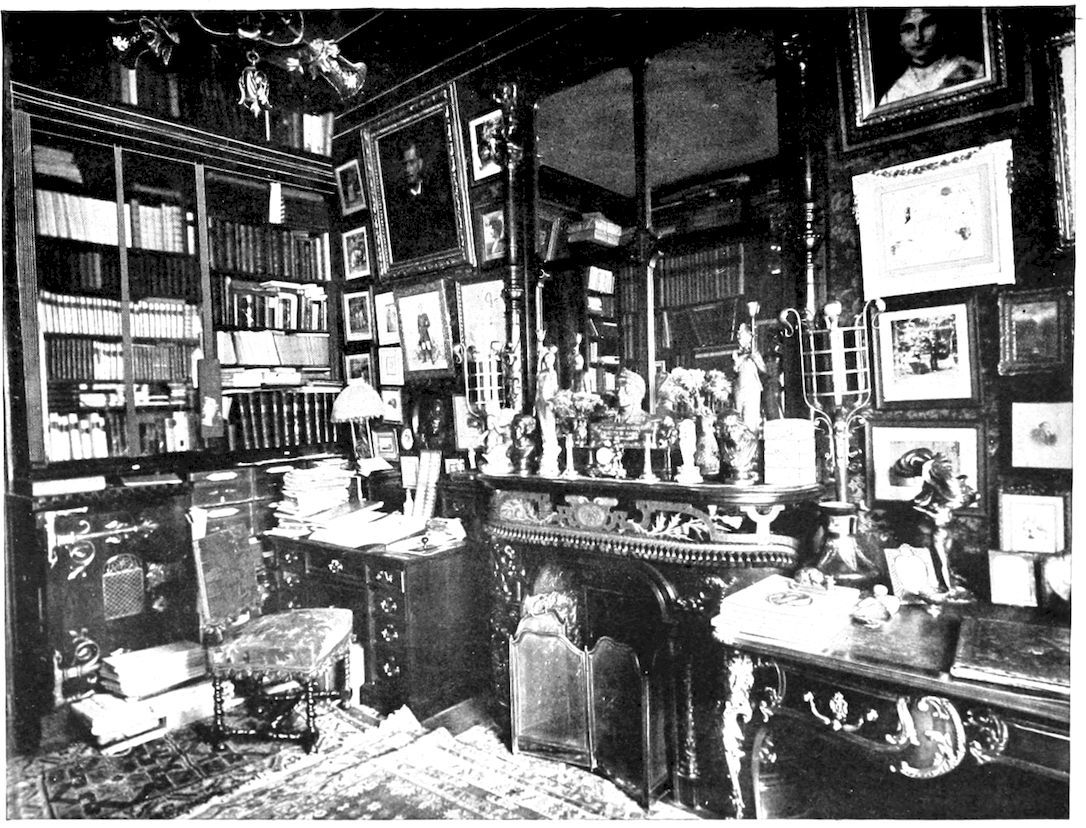

CORNER IN SARAH BERNHARDT’S LIBRARY, SHOWING MADAME BERNHARDT’S WRITING TABLE ON THE LEFT.

Who can say what schemes had floated through the minds of the poor fellow, who was perhaps half starved or perhaps excited by a clever, inventive brain? Perhaps when he stopped and looked at the jeweler’s window, he said to himself: “There is jewelry there worth 1,000,000 francs. If it were all mine I would sell it and go back to Belgium. What joy I could give to my poor mother who is blinding herself with work by gaslight, and I could help my sister to get married.” Or perhaps he was an inventor, and he thought to himself: “Ah! if only I had the money which that jewelry represents, I could bring out my invention myself, instead of selling my patent to some highly esteemed rascal, who will buy it from me for a crust of bread. What would it matter to the artiste? Ah, if only I had the money!” Ah, if I had the money!... Perhaps the poor fellow cried with rage to think of all this wealth belonging to one person. Perhaps the idea of crime germinated in this way in a mind which had hitherto been pure.