I WAS A BOY.

After I became eight years old, it was thought that we were old enough not to have governesses, which helped with the catering and sleeping arrangements. Our governesses were Austrian ladies who forced us to speak German to them and thus we were supposed to become proficient in the language. The Governess slept in our bedroom, making it a very cozy foursome. Poor little rich children.

Mostly we had more maids than beds and therefore one of them had to sleep on the settee in the downstairs lounge. At the time I could not understand why my 17 year old brother had to go downstairs to fetch himself glasses of water, but by the time I became the same age I not only understood, but envied his opportunities.

It requires no great imagination to realise the disturbance which the occasional overnight visit of my Aunt Margit caused. Who shall camp where became an exciting game of guessing and by the time we settled the matter of musical beds, it seemed that everybody had a change. Usually she finished sleeping in our parent's bedroom on a sofa, since the sitting room settee was usually occupied by a maid. However, much greater were the problems when one or the other of the children contracted a contagious disease, such as mumps, chicken pox or some other illness, which required Government decreed isolation, such as whooping cough, scarlet fever and the dreaded diphtheria.

With three children in three different schools we all managed to have our major illnesses at separate times and the required major isolation was indeed a major affair. Everybody moved out of the first floor and beds were made in the sitting and dining rooms downstairs. The maids made their beds in the kitchen and the upstairs laundry and food was cooked and transported upstairs for the sick child and Mother, who were locked up for the duration upstairs. Outside the house a large red sign declared it off limits to all except doctors and warned that any who came in contact with the inhabitants will have to be isolated also. The isolation lasted until doctors announced the sick to be cured and the Health Department's lorry and employees arrived to wash down the walls and take away everything else to be disinfected.

Scarlet fever lasts 6 weeks, as does whooping cough, while diphtheria is usually over in 3 weeks, (provided the child survives). We all had all these illnesses, except that I escaped whooping cough, (until the age of 40), but instead I was one of three children in the Hungarian medical history of the day, who contracted diphtheria for a second time.

The first time I had diphtheria I managed to finish up with a heart ailment. The second time I became ill on the day my Mother left for a conducted tour of Italy. We waved her off at the station and visited my grandparents on the way home, when I became sick and started to shake from the fever that suddenly erupted. My father contacted our lady doctor who specialised in children's diseases, who came immediately and suspected diphtheria, which the assorted visiting professors who were ferried up to the house at great expense eventually confirmed.

There was some question of recalling Mother, who at this stage was still on the train towards Italy, and another possible alternative was that I should be taken to a hospital. In the end it was decided that I should remain at home and our "Aunt Doctor" Miss Rella Beck moved in to live with me for the duration of my diphtheria. Also, my Father's Uncle's widow, Sari Kellner, who was almost totally deaf, came to become my nurse. Her self-sacrifice in allowing herself to be incarcerated was greatly appreciated, but as far as I was concerned it became an additional hazard to my survival. I was constantly exhausted from having to shout to make myself understood and additionally she was such a tremendously high spirited and good humoured person that she made me convulse with her stories and I had constant laughing fits, - not to be encouraged for a dying child.

On the evening when we were expecting Mother to return from her Italian holiday, she kept me laughing by telling me about her daughter-in-law who used to chew the nail varnish off her fingers whenever she was nervous. The practical demonstration my Aunt Sari gave was allowing me to concentrate on laughing instead of being preoccupied with Dr Beck's effort in keeping my heart going with injections, while I was having one heart attack after another.

Mother arrived that evening and over night my condition deteriorated sufficiently to be declared an intensive care case and at 5 a.m. Mother and I were picked up by an ambulance and taken to a hospital where my condition immediately improved. Nevertheless, I still had to stay in hospital for some 4 weeks recuperating and even when I could return home, I had to stay another 4 months in bed, receiving daily injections to keep my heart going at the required speed.

Our routine at home had to change, because Mother became my nurse and could not leave home. Instead her relations and friends made the pilgrimage to our house. I spent my days in the children's room upstairs, or else the maids set up a deck chair in the garden and I was carried by one or two of them to lay in the deck chair all day. In the end I had to re-learn to walk again and over a period I was allowed a few minutes longer every day to be up and walking slowly in the garden.

Our garden was looked after by gardeners and Father who attempted to drown the plants by watering. In the front we had a rather unkempt lawn (these were pre-lawnmower days) in the middle of which was a flower-bed full with rose bushes. Another flower-bed, also overrun with rosebushes, was surrounded with a pedestrian path, and another one, intended but never used for cars, both of which were covered with red gravel.

We used these paths to ride our bicycle against the stopwatch and on falling off, collected the most awful gravel rashes in the process. Anti tetanus injections were handed our rather freely by our Aunt Doctor, causing John to react by fainting fits and being in much greater danger from his injection than from tetanus.

Planted in the front garden, just inside the 2 meter high wrought iron fence were two poplar trees. One of these was struck by lighting and grew up to be shorter than the other. Because of the size difference they were popularly referred to as Jancsi and Pista, my brother's and my nicknames.

Immediately in front of the house and in fact partly covering the window of the children's room was a magnificent wild-almond tree. Two stories high, it survived the building of the house, which was one of the first houses in the as yet unnamed street. When somebody asked Father if he has any suggestions as to what name he should apply for the street, Father remembered the almond tree on the site and suggested "Almond Street" and thus "Mandula utca" was born, named after our "mandula" or almond tree.

The garden in the rear was used to provide us with fresh fruit off the trees and bushes. We had wonderful cherries, including a white variety, strawberries, blackcurrants and all types of berries, which we enjoyed eating, before or after they ripened.

There was also a very small area grassed on which we were supposed to play football, but being too small it was seldom utilised. We preferred using the empty block next door, even though it was not very level. The backyard also had some drying lines erected between trees and on the back wall of the house there was a "klopfer" e.g. two hefty wooden rollers mounted away from the wall onto which the persian carpets could be hung and beaten by cane carpet beaters. Another use for these carpet beaters was that, while we were small, we were constantly threatened that they will be used on our backsides.

The whole property was surrounded by high fences, ornamental in front, wire fences on the sides and in the rear, topped up by lines of barbed wire to keep unwelcome visitors out. In the front, affixed to the ornamental fence was an engraved marble plaque, telling the admiring public passing by that the house was designed by Mr Emil Vidor, “Master Art Architect”. When somebody pinched the marble, Father received a letter from the solicitor of the architect reminding him that the contract stipulated that a marble plaque will commemorate for ever the art of Mr Emil Vidor. Mr Vidor's pride in our house was not entirely misplaced, because it looked quite acceptable from the outside, it was only the inside which was so utterly messed up.

We usually had dogs, sometimes more than one. These were not pets, but trained guard dogs, and were kept on the chain all day and allowed to roam in the garden during the night only. Unfortunately, our dogs did not last very long, they were either too vicious or too friendly.

One of them was in the latter category and therefore was sentenced to be banished into the country where a kind farm manager was prepared to accept him for re-schooling in the art of scaring off burglars.

The dog, (named Hacsek after the more comic member of a Laurel and Hardy type of cabaret act), was duly taken by one of Father's country salesmen deep into the country and poor old Hacsek was replaced and forgotten, until months later a bedraggled and thin Hacsek arrived at our door step. Of course we had to keep him and his successor, a St. Bernard monster, was renamed to become "Sajo" in honour of the other member of the comedy duo. The two dogs became inseparable and both were guard dogs in name only. Hacsek and Sajo were the closest we came to having pets. (There are several versions for the naming of the dogs, this is one of many!)

There were two cellars under our house. One of them contained the coal and the heaters, which were coal fired. The other contained the janitor and his wife and usually a child. The janitor's "flat" contained just one basement room with a toilet outside and a wash hand basin which was open to the weather. All this was underground for the most part, although there was a high level window strip along the uppermost portion of the wall, which allowed some air and light to enter.

The janitor, who also doubled as the driver of our car and his wife, who was one of the cleaning ladies, were responsible to keep the fire going in the cellar. To feed the oven with coal, about a yard from where they were living, they had to leave their room, go upstairs into the backyard, enter the house through the kitchen, get into the area where the icebox was, pass the toilet, enter the entrance hall, go under the staircase, open the cellar door and walk down the steps. Imagine this performance two or three times a day, in rain, snow and sludge, allowing the heat to escape and carrying in the mud.

The congestion in the kitchen was amazing and unceasing. The cook was cooking, the janitor's wife was carrying carpets from upstairs to be beaten in the back yard, the maid was cleaning silver, Irma was cooking her dietary food, the children were eating bread with goose liver and the janitor was slaughtering some chooks.

The only persons, who except for meal times, were not to be seen in the kitchen, were the gardener (who only came once or twice a week), the washerwoman and the ironing lady, (who both came once a week). We also had a lady who came for two days at least once a month to sew shirts, pajamas and underwear for the children and Father. The Singer sewing machine was kept in a corner of the stair case and traffic to upstairs was thus impeded when the monthly sew-in was in progress; yet another monument to architectural ingenuity.

Mother did not spend much time in the kitchen and if she did, it was not for cooking or preparing something. She usually got up for breakfast with her husband and then returned to bed. The cook and Irma, after she returned from hospital, came along to sit at the end of her bed around 9 and they had a conference about the day's menu. With the exception of the meat, which was ordered in Town for delivery by Mother, the chicken, eggs and the geese were delivered on a regular basis by some peasant women, and our cook was responsible to buy the ingredients, such as rice, flour and salt from the traveling grocer.

Through Father's connections in the country we were given a lot of game. Thus we ate a lot of pheasants, venison and rabbit and also quite a lot of fish. Thus shopping for food was not an important part of Mother's life, although visiting shops was an all consuming passion for her.

On the other hand Mother spent a lot of time in fashionable coffee shops. After delivering Father to the swimming pool for his daily swim and then driving him to work, the chauffeur usually returned and drove Mother into Town, where she either met her friends over coffee or visited members of her family. She became a charitable and thus beloved lady of her family which, having started well off, became more impoverished as time went on, while my Father was doing better than ever. Not so my Mother, who was kept on a very tight rein, and had to ask his permission before spending any money outside her housekeeping allowance.

They were genuinely and quietly charitable. For instance we had Irma, a young peasant girl from the country as a junior maid, who developed some illness, which necessitated hospitalisation, soon after she joined us. Poor Irma spent 5 years in hospital and my Mother visited her every week, kept her in clothing and pocket money, and even sent sums of money to her father. When she was ready to leave hospital, she returned to us to be a semi-invalid in our home for another 4 or 5 years, being looked after by Mother and the other maids and the cook.

In 1944, when anti-Jewish regulations forbade her continuing to be a "servant" with us, she had to leave, thus becoming unemployed and she returned to her village and her drunkard father. After the end of the war she could hardly wait to hear that we are prepared to take her back. She returned to us as soon as she could. Soon she was very sick again and I remember my Mother and I, in the snow, pushing her on a toboggan to Mother's doctor, waiting while she had surgery under local anesthetic, taking her back home and carrying her upstairs to her bed.

She never recovered fully and she never left us. We left her when we left Hungary, but not until she had been taken over by a relation, in whose home she died after a life of being looked after by and working for our family. She was 38 when she died.

We children were brought up by a large number of nurses, maids, cooks, chauffeurs, and teachers. We were both shockingly bad at school, a luxury we could afford, since our own teachers from school secretly coached us in the afternoon, and we knew that their fees for that were higher than their salaries from the State. So we didn't need to bother much, knowing that in spite of what Father was preaching, we could not fail our school exams.

In addition to being coached by our teachers other experiments were tried, including sending us to do our homework with relations whose children were doing well in school, without being nagged by their parents or having the teachers bribed. This method was not very successful either.

As soon as the school holidays started we children were away on learning a language. John was sent to summer camps in Austria first and later to St Gallen in Switzerland. I was first sent to the German speaking part of Czechoslovakia and when that part of the country become Germany I had to spend my summer holidays in Austria. Luckily for me, Austria was taken over by Hitler in 1938 also and thus at the age of 12 I was allowed to have a holiday without the ulterior motive of learning German.

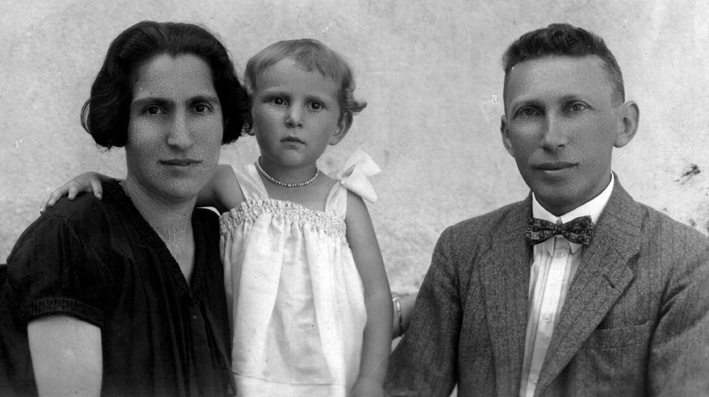

From then on I was sent to spend time with my cousin Eva and her parents in the small village of Szölösgyörök, 7 kilometres from Lake Balaton. I must say, that I enjoyed being there. I was getting on well with Eva and her parents were delightful. Her mother, Aunt Margit was my mother's younger sister and she was a quiet, helpful and gentle woman who lived very happily with her husband Uncle Bandi. He had excellent humour and he was a lot of fun. He had all the time for us children, taught us card games and beat us at chess and told us stories of his youth and his relations and played the cimbalom for us.

My uncle had one of the two shops in the village, and we visitors were allowed to help serving the customers, all of whom were peasants or farm labourers and their families. If the Vadász shop did not stock something it was only because it wasn't made or grown and nobody but him knew where to find the rare treasures he had put away for the unlikely event that somebody might ask for it. He sold everything from groceries, such as bulk sugar and flour to underwear and fabrics, kerosene and homemade soap, not to mention farming tools and building materials. The only thing he did not stock were electrical appliances, because there was no electricity in the village.

The "laird" i.e. Count Jankovits, who owned half the village and almost all of the land around it, was of the opinion that electric light is bad for your eyes and therefore did not allow it to be connected. And that was that. He also had a stone fence, with glass embedded on top of it, right round his 30 acre park and when he visited the village church once a year, the side where his pew was had to be kept free of people, as he did not wish anybody to sit behind him. In spite of it all he was revered by the village people. I doubt if he reciprocated their feelings and must have regarded the people of the village as his serfs.

My Uncle Bandi was also loved by the inhabitants of the village but for a different reason. The peasants and farm labourers of the village were always broke and Uncle Bandi had the most elastic slate ever. No one was ever refused credit or a handout of some flour or sugar by Uncle Bandi. Often a sick person sent a child for some food and he used to send more than they asked for.

Uncle also had a small amount of land which was bearing maize and grains. He hated cattle and kept no cow, but fattened pigs and had geese (which were force fed by hand to produce the famous goose liver) and poultry, which was picking away for feed in the yard or outside on the road. There was little danger for the chicken to be run over, the traffic on the road consisted of the once daily arrival of a large car, which was the "bus" and maybe twenty horse or oxen drawn carts per day.

There was also the picturesque departure in the mornings of the various herds, first the cattle, then the goats and sheep, followed by the pigs and finally the geese. They were herded along by kids, whose job it was to lead the animals from the peasant houses along the main road to the various communal grazing areas and then bring them back in the evening into their sheds and stalls. It was amazing to see these animals hearing the bells of the lead steer and setting out to join the herd and in the evening, when unerringly they found their way back to their own cow shed. The same applied to the pigs and the geese, except they required no bells and supplied their own sound effects.

Aunt Margit and Uncle Bandi always had at least two horses which were used on the field and to take grain to and from the mill, and most importantly to be harnessed by the coachman in front of the sulky and transport us in luxury to the Lake for our days on the "beach".

Lake Balaton is Europe's largest lake (about 75 by 14 kilometres) and became the "Riviera" of Hungary. All around it holiday resorts were built, with hotels, casinos, health resorts, etc. The lake was used for swimming and all types of water sports, especially small yachting in the summer, while in the winter ice yachting was possible on the frozen lake.

Through Eva I made lots of friends and our days at lake side were always happy. One of our friends was allowed to use his parent's sailing boat and we had long and exciting sails, darting in and out of small bays where fish was just asking to be caught.

Back in the village I had many other friends who were different from what we were meeting back in Budapest. There was the blacksmith, who allowed me to pump the bellows and tried to teach me how to shoe a horse. Then there was Uncle Geleta, the little coachman who looked after the horses and who allowed me to drive the cart and sulky. I also knew the some years older son of the count's farm manager, who was quite friendly to me, - no doubt instructed by his father to look after me, due to the fact that the farm was a customer of my fathers firm.

This boy, whose father was quite high in the village pecking order, took his duties of looking after me quite seriously and thus on one occasion made me an offer which I did not have since. One late afternoon I was in his company in the count's park when sex entered our conversation. I did not dare to admit that at the age of 15 I still had no practical experience in these matters and when he suggested that he will get me a partner, I was too petrified to refuse his offer.

He took me near the path where the farm labourers or their children were approaching the count's dairy for their daily ration of milk and suggested that I pick any girl. When I did not, he stopped two young girls, told one of them to go with me beyond the bushes and disappeared with the other. I followed the girl, who lay down on the grass, lifted her skirt and waited for me to do the expected.

I made her promise not to tell my refusal to consummate with her my friend's kind offer and sent her away after a decent interval to fetch her milk. Eventually my friend returned from his escapade and I thanked him for the wonderful time I had with my little girl friend, who must have been about 14 years old.

The village was run by petty officials, who received their orders from the Count and the officials of the shire. Nevertheless they were approachable and appeared to be benevolent. On the other hand, the two gendarmes, who were in charge of public security in the village were regarded and acting as semi-gods. Just to sight them was sufficient for grown up and innocent men to become silent and frightened. The most raucous revelry in the pub ceased when they arrived to have a drink, for which they did not even offer to pay. At the slightest pretence they chained up people and beat them into confessing, whatever crime they wanted to solve. I remember them walking into Uncle Bandi's store, selecting whatever they fancied and suggesting that he puts the debt on their never-to-be-paid slate.

While John and I were on our various holidays, Mother and Father had a chance to be on their own, but of course our absence was used for them to go their separate ways. Mother some times went to Oradea-Mare in Romania to visit her Aunt Szidonia or just stayed at home, while Father went to places abroad, - on his own. Wherever they went, the important thing seemed to be that the children went somewhere else. But even then, my brother and I were never sent to the same foreign place together, - in case we were to speak Hungarian to each other.

From the age of eight, I cannot remember ever spending a holiday with my parents, although in December 1937 I was taken along a business trip by my Father, after which we stayed two days in a big hotel at Balatonfüred. On the second morning, just before we were to leave the hotel I decided to test the emergency light arrangement, which consisted of a candle and match. It worked and the staff, with the help of the resident fire brigade saved the hotel, even though the room, together with our luggage was burned to cinders.

My Father paid up for the curtain, carpet and furniture and we travelled back home without a single word being said during the 4 hour trip. The road was covered by ice, but the mood inside the car was a great deal icier. On arriving home the day before Christmas Eve, my Father immediately blamed Mother on my becoming an arsonist, they had a fight and in this fashion Christmas 1937 was as much a write off as many other occasions became due to the bickering of my parents.

There is no doubt that our parents meant well. Just the same, even in a community which was peculiar, and deserved to be subjected to violent change, our parents were special. They lived the sort of life which cannot be described. They were both larger-than-life characters, and they continued to be just that until they were approaching 90 and in a strange country, where they continued to enrich and unnerve and disturb and amuse all who came in contact with them. Their "little" boys, well into their fifties still found it difficult to communicate with them and they still felt endangered by their constant criticism. They continued to fight, worry and care for each other right up till they were parted by the death of my father, in his 90th year.