HISTORY

The Czechs and the Hungarians had some problems in 1916. Twenty years later I found out that I was Hungarian, when at the age of 9 I was pushed into a stream by some Czech kids while attending a holiday camp at Spindlermühle in the Sudetenland part of Czechoslovakia. When, desperately unhappy, I wrote to my parents wanting to go home, I received encouraging letters and finally a visit from Father, who was on his way to take the cure at Karlsbad. He explained to me that if I wanted to become a "Weltreisender" and his assistant, I must learn German and I therefore had to stay.

I became wet once again, when a year later, while in a holiday camp in Gars-am-Kamp in Austria, I found out that I was Jewish. This time I was thrown fully clothed into a lake by an Austrian Nazi, who was one of the teachers there.

I was quite surprised and disappointed at this as I did not regard myself in any way different from other people or kids. In fact, while I was thus "enjoying" my holiday in Austria, the 1936 Olympics were celebrated in Berlin. The radios were blaring forth about the fabulous German organisation, Hitler's pride in the victories of the German athletes, etc... I was also enthusiastic and proud and most impressed with the achievements of Germany and even Herr Hitler. Being 10 years old, it never occurred to me that I have a problem with the rulers of Germany or vica versa.

I was especially excited listening to the Olympic broadcasts since the Hungarians were doing very well. Ten Gold medals and scores of silver and bronze medals placed the Hungarians third in the Olympics, being beaten only by Germany and USA. Little did I know that one of the Jewish Gold Medal winners will die while serving in the same battalion as I and the brother of another will be rescued by me from a concentration camp.

At the age of 10 I was not really interested in religion, but I suppose that being thrown into a freezing lake, when unable to swim made me interested in the reasons for receiving special treatment and also I commenced reading newspapers, where almost daily there was some reference to some government decree limiting the Jews of Hungary. Nothing as serious as was the case in Germany, but it was obvious that the traditional anti-semitism of the Hungarian population would be nurtured as the official policy of the Hungarian government.

On the other hand, Mother was religious. When she was only 10 years old she lost her own Mother, whose parents she thereafter lived with. Mother was the eldest of two girls, Ilonka and Margit, and two boys, Jenö and Imre. Her father remarried after being a widower for some 6 or 7 years, an action which was considered hasty and thus he was never forgiven by the family of my great-grandmother.

The new stepmother was not a particularly lovable or happy person. Emilia, daughter of a Baron, known as Anyika was a shy, quiet old lady all her life. The second marriage produced one son, Zoltán, who was ignored by everybody including his own father, but excepting Mother who was always very good to her Stepmother and Stepbrother.

So was Father who, on my Grandfather death in 1925 insisted that Mother and her brother and sister should renounce their inheritance in favour of the Stepmother, who was left intestate by my Grandfather. This in turn made Father less than popular with some of those who thus lost their inheritance. Not that there was a great deal left by my maternal Grandfather and my parents had to help his widow and son during the 19 years she survived my Grandfather.

Mother's life on the farm of her grandparents wasn't easy. Her grandmother was running the show and let every body know it. She looked after the two Tauszig orphan girls, (while the two boys stayed with their Father) and additionally three little Pick girls: Tusi, Lenke and Lili. Mother was the eldest of the Tauszigs and had to take an active part in bringing up the others.

When later she met and fell in love with my Father, she found that everybody was against her choice. To allow a Bank Director's daughter to marry the son of a Blacksmith-Tailor-Shopkeeper-Publican, whose major asset was that he was handsome in his hussar uniform, was a catastrophe too bad to contemplate. Permission to marry was refused, and this decision was re-considered only when my Mother was found unconscious with her head in the gas oven.

Those days there was a tremendous emphasis to ensure that the classes were kept apart and inter marriage between the rich and the poor was not encouraged and was just as undesirable as marriage between a Jew and a Gentile or a White and a Negro. Luckily, due to the absence of Negroes, there was no colour problem in Hungary.

My maternal grandfather was a well educated gentlemen. He worked in a Bank all his life and became the Manager of the Branch in Szekszárd, a medium sized town, known for its excellent wine. His official title was "Bank Igazgato Ur" (Mr Bank Director) suggesting a grandeur not easily understood these days. Additionally, he had a vineyard and thus he was a Property Owner. Had he not been Jewish, he could have been one of the "landed gentry". He certainly tried to behave accordingly, without accumulating much in assets.

If that would not be impressive enough, my Mother's maternal grandparents, the Pick's of Szilasbalhás were big-time land owners or at least renters of land. They were also against this mismatch and were sure that Father is a fortune hunter who was only interested in the sizeable dowry, which used to be part of the marriage settlement those days.

Father's parents were not too keen either. They must have felt totally outclassed by Mother's Bank Director father and the landed grandparents. They could see nothing but trouble and in any case they disliked their future daughter-in-law, who was pretty, well dressed and educated, could not cook or sew and was more interested in playing tennis than in becoming a shop keeper.

That they got married against such odds was due to the willfulness of Ilonka, who must have believed to have found the dreams of her life in Józsi. She fought for the right to make her own decision and it was finally one of her uncles, Uncle Dezsö, the only person who trusted the Hussar Corporal who became my Father and who believed that he will make it. Uncle Pór Dezsö became her only supporter in her wish to marry Father. Luckily for them, Uncle Dezsö was the favourite and most successful son of my Mother's grandmother. This rotund and bossy matriarch finally gave her blessing to the wedding and that was that, - my Mother got what she wanted.

Ten days before her wedding, her eldest brother, Jenö (Eugene) Tauszig died in the Spanish Flu epidemic and she herself was so sick that doctors wondered if she would survive. She did and the wedding took place. The same week revolution broke out and communism was declared in Hungary.

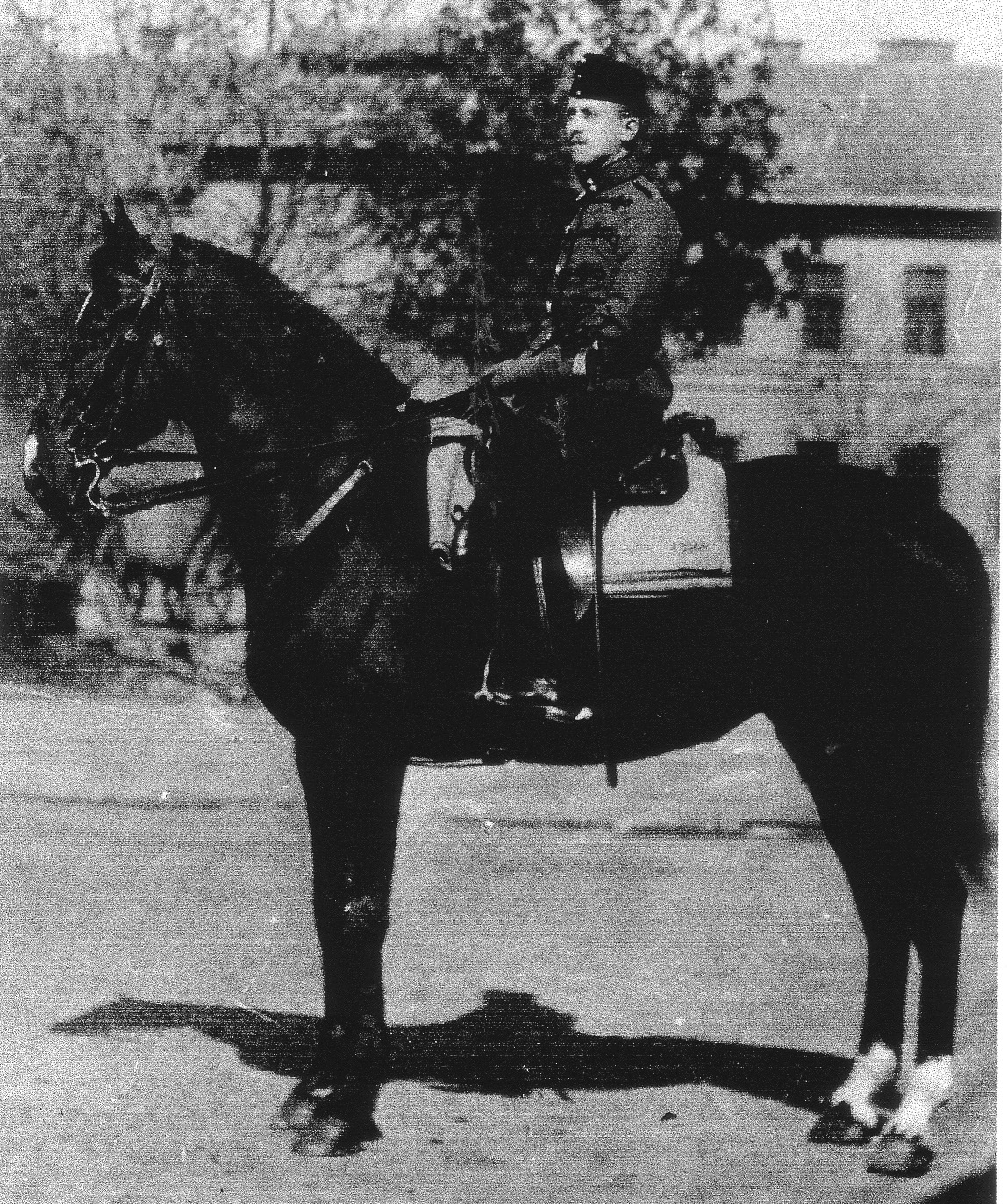

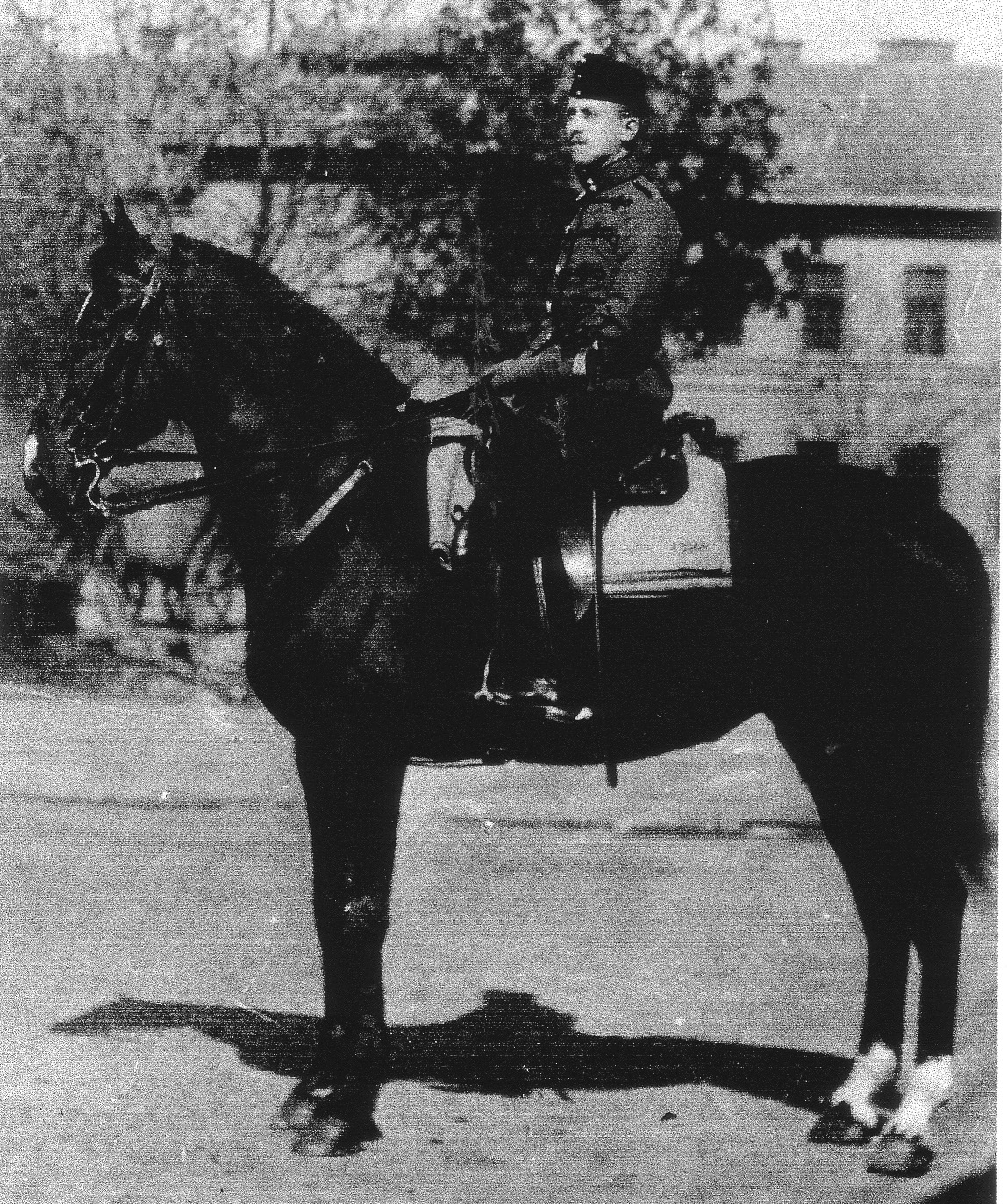

Four years earlier, at the outbreak of the war in 1914 my father was 22 and to his horror, when mobilised, became a recruit of the famous 10th Hussars. They wore black boots, red pants, sky-blue and red jackets with heavy gold braiding and a fur lined jacket with fur collar on their left shoulder, to leave their right hand free to wield their sabres. They never went anywhere without their spurs, which could be heard from a distance and caused the girls to look for their idols. They were the elite of the elite, and were the pin-ups of all the Hungarian girls, a welcome compensation my father never failed to fully exploit during his 5 years as a 10th Hussar.

They certainly needed some compensation because they had a hard life. While other soldiers had to rise at 4.30 a.m. the hussars had to start earlier and look after their horses. Their training was inhuman, they rode for hours and hours, with and without saddle, with arms crossed in front of their chest to acquire a perfect balance. Their behinds were bleeding and their pants had to be soaked off once the blood congealed. At least one peasant boy used his pistol to blow his brains out, - he just could not take any more and Father too contemplated to get out of it by self-mutilation.

In addition to being the best dressed Hussars in the Austro-Hungarian Army, they were also expected to charge on horseback with nothing but their colourful uniforms and shining sabres against the Russians who had the sense to use machine guns. Two out of three Hussars died in that first attack, four fifths in a subsequent attack. As luck had it Father stayed behind due to a combination of knowing the right people, illness and bribery. He survived while many of his comrades did not.

Neither did his favourite uncle, Jenö (Eugene) Kellner, who became the first Hungarian officer to die in the Great War of 1914-18, during an attempt to save one of his injured soldiers. He left a widow and three small sons to be compensated by a small pension and a gold medal.

It is not correct to say that Father was penniless. When he joined the army he was a salesman with a plumbing supply company, who had such high regard for this 22 year old, that they paid him a retainer throughout the war, on the understanding that he would carry on with them after the war finished. It was ironic that at the outbreak of communism in 1918 the firm was closed down and Father could not rejoin them, although he kept their catalogue as a memento all his life.

His parents had nothing. Originally they lived in the village of Nagyperkáta (and on the outskirts of that, called "Gypsy Town" to suggest that it was the worst area), in a house which had no glass windows. During the summer the "windows" were open, but during winter they were filled up with similar mud from which the whole house was built.

Grandfather had very little education, but my Grandmother came from a "better" family and was better educated. He was a big, good looking man, commonly known in the village as "Beautiful Paul". She was small and totally devoted to her children and her spendthrift husband, who was more interested in being beautiful than in providing for his family. They had four children, but only two survived more than babyhood, in spite of the fact that contrary to the practice of those days, my grandmother refused to give her babies brandy as a pacifier to stop them crying!

There is no doubt about their son being their favourite child. On one occasion Grandfather bought a new horse (he was forever trading-in his own horses, while contracted to the Army to supply horses to them as did Mátyás, my great-grandfather) and young Józsi happened to be sick in bed. He nagged his parents, wanting to see the new horse and wanted to get up to visit the stable. To save arguments and to ensure that their son will be satisfied, his father brought the horse into the house. Spoiling children is obviously not a new fad.

My grandmother was reputed to be a very resourceful and intelligent woman. She was also long suffering and hard working. She must have realised that her husband cannot be relied upon to keep the family going and has set herself up in business. She purchased apricot and plum brandy in bulk from some of the illicit backyard distilleries, refilled them into tiny bottles and sold them to the peasants between 3 and 4 in the morning, as they went off to work in the fields. They banged on her door, she gave them the bottle, which they knocked back in one gulp with the result that the burning taste wakened them and made their daily tribulations easier. She waited for them to finish, reclaimed her bottles and refilled them again in time for next morning.

A famous story about Beautiful Paul is his visiting his 20 years old son (my Father) in Budapest, who wanted to make the old man's visit to the big city memorable by taking him to the cabaret. When he noticed the "risque" pictures outside the restaurant-cabaret, Grandfather was reluctant to enter the place. Eventually my Father-to-be and his friends won the argument and the group of 7 or 8 sat down at their reserved table close to the stage.

t wasn't until the second half of the performance that one of the dancers called down to Grandfather: "Hi, Uncle Paul, how are you, we haven't seen you for months!"

My grandparents were actually called Kellner Pál and Katalin, nee Deutsch. As it happened, grandfather's name was really Bernát, but obviously he did not like it and called himself Pál. Thus three generations of men were Kellner, Kálmán and Colman respectively.

With the exception of the boys of the late First Lieutenant Jenö Kellner, who retained their name all their life, we knew of no relations who were called Kellner and thus it was quite a surprise to my brother and I to read in 1981 that Sir Alexander Korda was born a Kellner, in a village not 100 kilometres away from Nagyperkáta where my grandparents lived and my father was born. It turned out that while my father knew that family as being related, not until we showed him the book about the Korda brothers, that we worked out our connection and a distant relationship with them.

Father received only the minimal education the law prescribed. He left school at the age of 14 and earned his keep from then on. He read everything he could lay his hands on, and became extremely well informed on all matters: technical, engineering, agriculture, accountancy, politics, you name it. At the same time he was never a know-all, on the contrary, he invited people to explain things to him.

He was interested in everything that furthered his knowledge and kept learning and enquiring to the age of 89. In spite of a deficiency in spelling he developed a calligraphic handwriting style which stood him in good stead later. By the time he was 24 the army picked him to become a telegraphist and sent him to be trained to Vienna. In today's terminology he would be called a Telecommunications Specialist, - not bad for someone with almost no education.

After their wedding and a one day honeymoon in revolutionary communist Budapest, Mr and Mrs Joseph Kálmán moved into a flat into which, they and other families were sent by the authorities. Eventually it became their flat, (with only Father's parents moving in with them), but in the meantime they were lucky to share it with others. They had no income, the only thing they had was the dowry which Father received, after signing an approximately 30-page agreement prepared by my maternal Grandfather's solicitor.

The dowry was supposed to have been quite considerable, but in fact was insufficient to start a business and thus Father had to borrow money from his brother-in-law to buy some bankrupt stock of hand tools. His decision to buy these, without permission, so upset his father-in-law that, in accordance with the agreement, my Grandfather insisted that the dowry be repaid. While the arguments went on, the business became viable and Father could borrow from his Bank to repay the dowry. Inflation then set in and while Father eventually repaid his debt to the Bank at a time when the whole loan could be equated with the cost of a box of matches, the repaid dowry in Grandfather's hands was invested badly and lost its value.

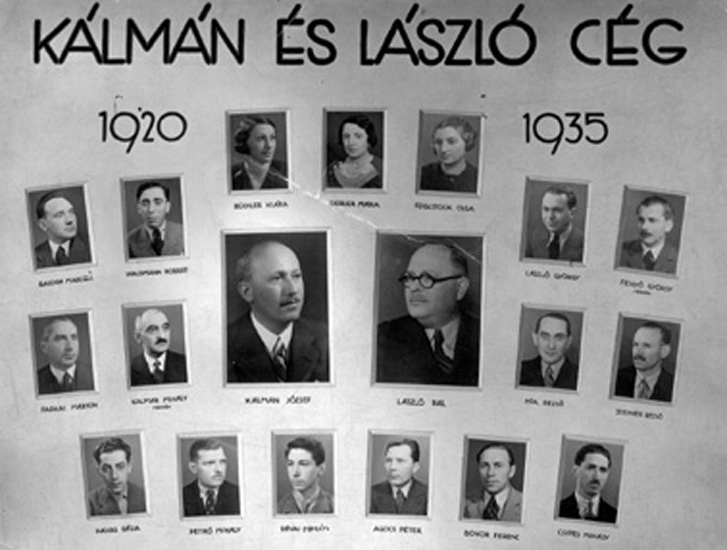

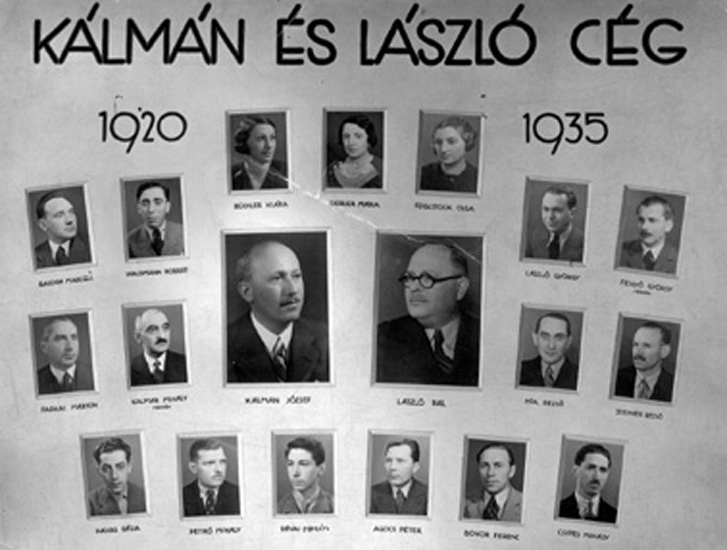

To house the stock of hand tools, Father opened shop in a basement and commenced to sell his hammers, spanners and nail punches. Paul László, his sister's husband, who was in a similar hardware supply business, left his job and joined him. They were partners and they remained so for twenty years, when due mainly to family intrigues, they decided to part. In spite of the bitterness accompanying the breaking up of a very successful business and partnership, there was never any recrimination between the two ex-partners, and I never heard Father speak of his brother-in-law and ex-partner in a way which could be construed as not complimentary. In spite of this, for years they did not speak to each other and competed in business with the intention of driving each other out of same. The photo shows my Grandparents with members of the László family with my Mother and me.

While partners, they complemented each other so well, that this must have been the major ingredient of their success. Paul, according to my Father, was the hardest working person ever; totally honest and reliable, while requiring the initiative and push that my Father supplied with great gusto and a lot of noise. It was usually Father who had the ideas and closed the deals, which Paul carried out. While Father flitted all over the place, Paul worked and worked. While Father traveled abroad on company business and on his frequent trips to relax, Paul stayed home and slaved away. This did not go unnoticed by Father's sister, who constantly told Paul that he was being exploited. In this she was aided by Paul's children, who further resented my Father's interference into their lives. One could only sympathise with the "children," who at that time were either married or have graduated as doctors of law.

There was also the competition between the two wives, - my Mother and Aunt. If one bought a new hat, the other had to have one bigger and brighter. When we built a house on the "Hill" the other family had to buy a house there and move into it earlier than us. Thus it was not surprising that the partnership was being undermined by the two wives and the children. (My brother and I are innocent. We were too young, but had we been older, we could not have remained uninvolved.)

During the duration of the partnership Kálmán & László flourished. They specialised in supplying all types of hardware to agriculture, and eventually became the largest in their field. Initially they imported spare parts for agricultural machinery, and later commenced importing specialised agricultural machinery mainly from Germany. Eventually, they commenced manufacturing machinery, such as hammer mills, which were designed on their instructions by young engineers, who eventually became leading academics in the agricultural machinery engineering field. Although originally copied from a German machine, with various improvements their hammer mill became the most advanced in any country and is still being manufactured in both Hungary and elsewhere, with very little change in design.

In partnership with Ohrenstein & Koppel they established a manufacturing organisation in Czechoslovakia and had a selling organisation in Romania, while their machine was manufactured under licence in Germany by O&K, who are now the largest makers of escalators and roadmaking machinery in the world

In 1938, to the delight of solicitors they parted. All their employees went to either one or the other partners, usually after a lot of intrigue and at increased salaries. The two new organisations, with Father alone running his, and Paul, with his son and daughter and future son-in-law working in the other firm, competed against each other and were successful in enlarging their share of business. Their new businesses were established not 150 yards from each other, in a city of one and a half million, and it became a rule of the two families not to pass in front of the other's business, in case using the neighbouring streets might be regarded as an act of spying.

Relations inviting one or the other family soon got used to the idea of not inviting both families at the same time, and in view of the fact that my paternal grandparents by then lived in Budapest and were visited by my Father every day without fail, a routine was worked out to ensure that brother and sister, and especially the two sister-in-laws never met. I used to visit my grandparents for many years at least 3 times a week, and cannot remember ever meeting my two cousins, who were probably visiting them just as often.

My grandfather had gout and sat in an armchair most of the time. He could hardly walk and had to be pulled up from his chair. This was done by my Grandmother, who was almost half his size, but who was determined to look after him, in spite of him being bossy and rude to her.

Both my grandparents were intimidated by my father. He always hated smoking and he must have been the pioneer anti-smoke campaigner. For health reasons doctors suggested that Grandfather cuts down his cigars to 2 a day, but Father went one better and simply forbade him to smoke.

My grandparents knew when their son will arrive for his daily visit and thus a great effort was made to ventilate and perfume the flat prior to his arrival in order to get rid of the incriminating smells. They didn't fool him and in fact, realising how much the cigars meant to his old man, Father used to give me money to buy some cigars for him, on the understanding that I do not divulge where the finances for my generosity came.

Even in her late seventies Grandmother Kellner was a very hard working intelligent lady, while my grandfather was and remained a lovable rogue. Everybody loved him in the neighbourhood, in spite of his immobility. Their flat was on the ground floor and he used to sit at the open bay window and make friends. No good looking girl between the ages of 19 and 40 could pass by without speaking to him and they seemed to enjoy his company as much as he enjoyed chatting them up. Right up to his death at 82 years of age he had an eye for the girls.

He must have been a chip off the old block because his father, Mátyás, or Matthias lived to be 94, which was particularly remarkable due to the fact that at the age of 91 he fell out of a window, which happened to be on the fourth floor.

This great-grand-father of mine lived with his daughter on the 4th floor of a building of flats and one day locked himself into the toilet. When he could not open the door, he tried the window and succeeded to fall into the ventilating shaft. On arrival to ground level, he must have fallen on to the rubbish accumulated over the years and this must have cushioned his landing.

After a while the toilet door was demolished to find the window open and that the old gentleman disappeared. They rushed downstairs fearing the worst, but he was not there either. Finally they found him in the nearby park where he was being entertained by the maids and governesses walking the dogs and the children. It was only some weeks later that they found out that he broke an arm in this escapade.

By the time I was born in 1926 my great-grandfather was not alive and thus I missed out meeting him. However, I did meet my maternal great-grandmother, whom I remember being as frightening as her reputation. As far as grandparents, I knew my mother's stepmother only and of course, I knew my father's parents well. Grandfather Paul died in 1941, while Grandmother lived till she was 87 and died in Hungary in 1949, by which time my Father, who absolutely adored her, lived in London.

She lived for the last 4 years of her life with her daughter and son-in-law, Father's ex-partner, in Budapest. At the time contact between England and communist Hungary behind the Iron Curtain was extremely difficult, yet my Father found some ways to send them money towards his Mother's upkeep, which did not cease when she died. Not until both his brother-in-law and then his sister passed away, did the regular financial assistance stop, although Father and his sister were never close.

My Kellner grandparents were interesting people and coped quite well with their two children, who were less than friendly with each other, yet shared the cost of their parents' upkeep. There was never any remark on their part as to the family feud, nor did they attempt to interfere. This is quite atypical of Hungarian parents, although having a family feud is anything but.

Around 1940 my grandparents celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary and in view of my grandfather's immobility a big luncheon was organised in their flat, at which all the factions of the two warring families actually shared a meal. Great care was exercised in the seating arrangements, so that they did not require to speak to each other.

It was not until 1941 when my cousin George died at the age of 29 after a short illness (meningitis), that a sort of a relationship was re-established and contact between the two families approached normality.