X

U. S. ARMY NOT INTERESTED

FROM the time that they knew their invention was practical, the Wrights wished to offer to their own government a world monopoly on all their patents and, still more important, all their secrets relating to the airplane. They thought it might be useful to the Army for scouting purposes. But as they had greater interest at first in learning more about flying and improving their machine than in making money out of it, they did not at once attempt negotiations with government officials at Washington. When they did make such an effort they received a rude shock. The United States Army not only didn’t believe there was any such device in existence as a practical flying-machine, but was not disposed to investigate.

At least one foreign government showed more awareness and more curiosity. In the autumn of 1904, the Wrights got a letter from Lieutenant Colonel J. E. Capper, of the Royal Aircraft Factory (a government experimental laboratory dealing with aeronautics) at Aldershot. He wrote on shipboard en route to the United States, and enclosed a note of introduction from another Englishman whom the Wrights knew, Patrick Y. Alexander, member of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain. (Alexander had called upon the Wrights at Dayton in 1902, with a letter of introduction from Octave Chanute.) Colonel Capper wanted to know if he might see the Wrights in Dayton when he returned eastward from a visit to the St. Louis Exposition. They told him they would be glad to see him and he came to Dayton, accompanied by his wife, in November.

Soon after his arrival, Colonel Capper frankly said that he was there at the request of his government. The Wrights told him of what they had accomplished during that previous season of 1904 at the Huffman field. Before leaving, Colonel Capper asked them to make his government some kind of proposal.

The Wrights made no haste about submitting a proposal to the British, but, on January 10, 1905, about two months after the Capper visit, they wrote to him asking if he was sure his government was receptive to an offer. In this letter they suggested that a government in possession of such a machine as they now could furnish, and the knowledge and instruction they could impart might have a lead of several years over governments which waited to buy a perfected machine before making a start in this line. The letter was signed: Wright Cycle Company.

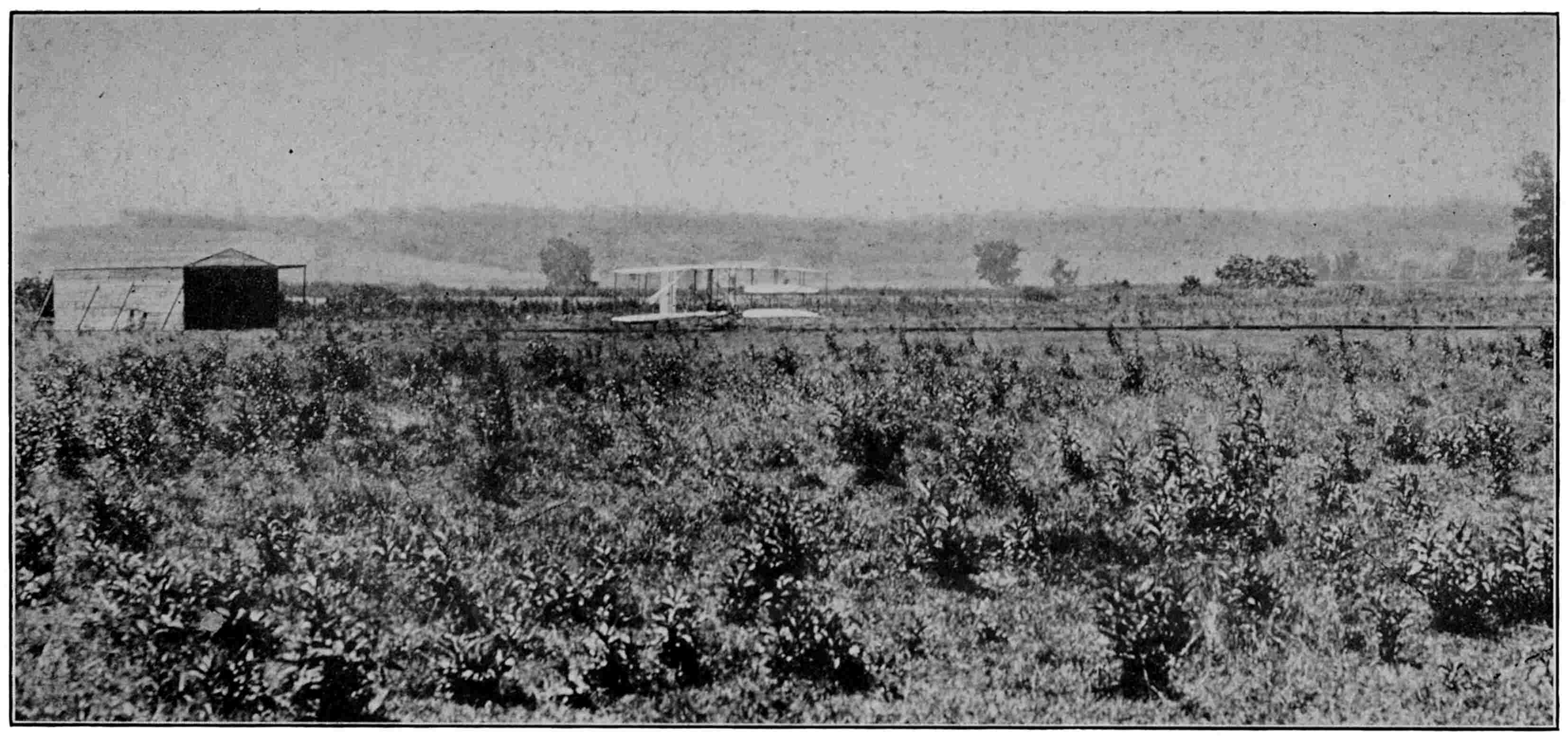

THE HUFFMAN PASTURE. This rough field, eight miles from Dayton, where the Wrights made their important experiments of 1904 and 1905, is now a part of Patterson Field.

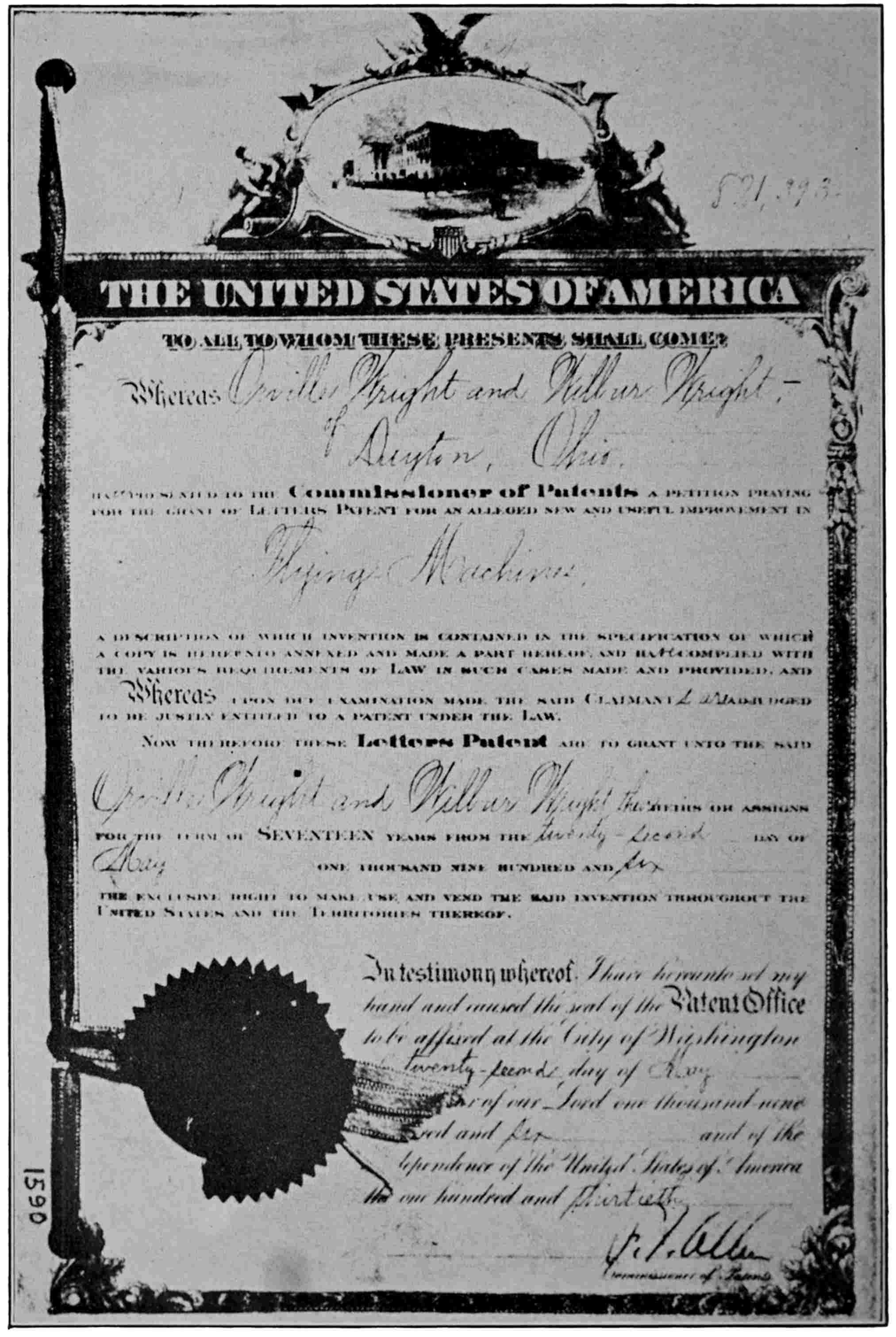

THE WRIGHT PATENT. Facsimile of the Letters Patent awarded Wilbur and Orville Wright on May 22, 1906, for their invention, the “Flying Machine.”

Whatever the British Government might desire, the Wrights did not intend to take any steps that could prevent the United States Government from having opportunity to control all rights in their invention for the entire world; and before having any further word from the British it seemed wise to learn from Washington just what our own government might want. They wrote, on January 18, 1905, to their member of Congress from the Dayton district, R. M. Nevin, as follows:

The series of aeronautical experiments upon which we have been engaged for the past five years has ended in the production of a flying-machine of a type fitted for practical use. It not only flies through the air at high speed, but it also lands without being wrecked. During the year 1904 one hundred and five flights were made at our experimenting station, on the Huffman prairie, east of the city; and though our experience in handling the machine has been too short to give any high degree of skill, we nevertheless succeeded, toward the end of the season, in making two flights of five minutes each, in which we sailed round and round the field until a distance of about three miles had been covered, at a speed of thirty-five miles an hour. The first of these record flights was made on November 9th, in celebration of the phenomenal political victory of the preceding day, and the second, on December 1st, in honor of the one hundredth flight of the season.

The numerous flights in straight lines, in circles, and over “S”-shaped courses, in calms and in winds, have made it quite certain that flying has been brought to a point where it can be made of great practical use in various ways, one of which is that of scouting and carrying messages in time of war. If the latter features are of interest to our own government, we shall be pleased to take up the matter either on a basis of providing machines of agreed specification, at a contract price, or of furnishing all the scientific and practical information we have accumulated in these years of experimenting, together with a license to use our patents; thus putting the government in a position to operate on its own account.

If you can find it convenient to ascertain whether this is a subject of interest to our own government, it would oblige us greatly, as early information on this point will aid us in making our plans for the future.

RESPECTFULLY YOURS,

WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT

Mr. Nevin forwarded the letter to the Secretary of War who turned it over to the Board of Ordnance and Fortification. That Board evidently regarded the letter simply as something for their “crank file.” They had received many proposals in the past from inventors of perpetual motion machines and flying-machines and had stock paragraphs to use in reply.

Their response to Nevin, signed by Major General G. L. Gillespie, of the General Staff, the President of the Board of Ordnance and Fortification, said:

I have the honor to inform you that, as many requests have been made for financial assistance in the development of designs for flying-machines, the Board has found it necessary to decline to make allotments for the experimental development of devices for mechanical flight, and has determined that, before suggestions with that object in view will be considered, the device must have been brought to the stage of practical operation without expense to the United States.

It appears from the letter of Messrs. Wilbur and Orville Wright that their machine has not yet been brought to the stage of practical operation, but as soon as it shall have been perfected, this Board would be pleased to receive further representations from them in regard to it.6

It will be noted, of course, that what the letter said bore almost no relation to anything the Wrights had written.

Having thus been brushed aside by their own government, the Wrights now might have been conscience clear to do as they saw fit with a foreign government. But nevertheless they determined that, no matter how public officials at Washington behaved, they would take no steps which could shut off their own government from use of the airplane if Army people ever got around to understanding the machine’s potential importance.

On February 11, 1905, the Wrights received a letter from the British War Office, asking them to submit terms, and March 1, without giving formal terms, they outlined in a general way what they were willing to do.

“Although we consider it advisable,” they wrote to the British War Office, “that any agreement which may be made at present be based upon a single machine and necessary instruction in its use, we would be willing, if desired, to insert in the contract an option on the purchase of all that we know concerning the subject of aviation ...

“We are ready to enter into a contract with the British Government to construct and deliver to it an aerial scouting machine of the aeroplane type ...”

Specifications included these: The machine to be capable of carrying two men of average weight, and supplies of fuel for a flight of not less than fifty miles; its speed, when flying in still air, to be not less than thirty miles an hour; the machine to be of substantial enough construction to make landings without being broken, when operated with a reasonable degree of skill.

Another provision was that the purchase price should be determined by the maximum distance covered in one of the trial flights; £500, or about $2,500 for each mile. If none of the trial flights was of at least ten miles, then the British Government would not be obligated to accept the machine.

There were further exchanges of letters between the Wrights and the British (altogether twenty-four letters in the years 1905–6), but the brothers began to suspect that the British were mainly interested in prolonging the negotiations as a means of keeping in touch and knowing what progress was being made in aviation. Probably, thought the Wrights, the British shrewdly foresaw that the flying-machine would not add to the isolation of the British Isles, and did not wish to hasten its development. But they doubtless wished to be well informed about whatever was happening in the conquest of the air.

The British War Office wrote on May 13, 1905, that they were asking Colonel H. Foster, their military attaché, in Washington, to call upon the Wrights at their “works”—meaning, presumably, at their shop—and to see their machine in flight.

The brothers were urged by their friend Octave Chanute on one of his visits to Dayton, to make another offer of their machine to the United States Army. Because of the treatment they had received from the War Department, the Wrights were naturally reluctant to expose themselves to further rebuffs, but Chanute was insistent that such behavior by Army people surely would not occur again. Thus prodded by Chanute, the Wrights, on October 9, 1905, wrote to the Secretary of War:

Some months ago we made an informal offer to furnish to the War Department practical flying-machines suitable for scouting purposes. The matter was referred to the Board of Ordnance and Fortification, which seems to have given it scant consideration. We do not wish to take this invention abroad, unless we find it necessary to do so, and therefore write again, renewing the offer.

We are prepared to furnish a machine on contract, to be accepted only after trial trips in which the conditions of the contract have been fulfilled; the machine to carry an operator and supplies of fuel, etc., sufficient for a flight of one hundred miles; the price of the machine to be regulated according to a sliding scale based on the performance of the machine in the trial trips; the minimum performance to be a flight of at least twenty-five miles at a speed of not less than thirty miles an hour.

We are also willing to take contracts to build machines carrying more than one man.

RESPECTFULLY YOURS,

WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT.

Once again the Secretary of War referred their letter to the Board of Ordnance and Fortification. Major General J. C. Bates, member of the General Staff, had become president of the Board since the previous correspondence, and he signed the reply. The Wrights blinked at the familiar phrases in the opening paragraph:

“I have the honor to inform you,” said the Major General, “that, as many requests have been made for financial assistance in the development of designs for flying-machines, the Board has found it necessary to decline to make allotments for the experimental development of devices for mechanical flight, and has determined that, before suggestions with that object in view will be considered, the device must have been brought to the stage of practical operation without expense to the United States.”

The letter went on: “Before the question of making a contract with you for the furnishing of a flying-machine is considered it will be necessary for you to furnish this Board with the approximate cost of the completed machine, the date upon which it would be delivered, and with such drawings and descriptions thereof as are necessary to enable its construction to be understood and a definite conclusion as to its practicability to be arrived at. Upon receipt of this information, the matter will receive the careful consideration of the Board.”

In other words, the Board would have to see drawings and descriptions to determine if the machine the Wrights had been flying could fly!

Regardless of whatever irritation they felt, the Wrights wrote to the Ordnance Board on October 19. In that letter they said:

We have no thought of asking financial assistance from the government. We propose to sell the results of experiments finished at our own expense.

In order that we may submit a proposition conforming as nearly as possible to the ideas of your board, it is desirable that we be informed what conditions you would wish to lay down as to the performance of the machine in the official trials, prior to the acceptance of the machine. We cannot well fix a price, nor a time for delivery, till we have your idea of the qualifications necessary to such a machine. We ought also to know whether you would wish to reserve a monopoly on the use of the invention, or whether you would permit us to accept orders for similar machines from other governments, and give public exhibitions, etc.

Proof of our ability to execute an undertaking of the nature proposed will be furnished whenever desired.

Here is what Captain T. C. Dickson, Recorder of the Board, wrote in reply:

The Board of Ordnance and Fortification at its meeting October 24, 1905, took the following action:

The Board then considered a letter, dated October 19, 1905, from Wilbur and Orville Wright requesting the requirements prescribed by the Board that a flying-machine would have to fulfill before it would be accepted.

It is recommended the Messrs. Wright be informed that the Board does not care to formulate any requirements for the performance of a flying-machine or take any further action on the subject until a machine is produced which by actual operation is shown to be able to produce horizontal flight and to carry an operator.

Such letters did not encourage the Wrights to press their offer further. As Wilbur expressed it, they had taken pains to see that “opportunity gave a good clear knock on the War Department door.” It had always been their business practice, he said, to sell to those who wished to buy instead of trying to force goods upon people who did not want them. And now if the American Government had decided to spend no more money on flying-machines until their practical use should be demonstrated abroad, the Wrights felt that there wasn’t much they could do about it.

Chanute, too, was now convinced that the seeming stupidity of War Department officials was not accidental. His comment was: “Those fellows are a bunch of asses.”

On that same day, October 19, when they wrote to the Ordnance Board, the Wrights had sent a letter also to the British War Office amending their earlier proposal. They said that recent events justified them in making the acceptance of their machine dependent upon a trial flight of at least fifty miles, instead of only ten miles as in the original offer.

Shortly afterward, on November 22, 1905, the Wrights received a letter from Colonel Foster, the British military attaché in Washington, asking if it would be possible for him to see the Wright machine in flight. Experiments for that year had been completed; but, the Wrights replied, if Colonel Foster came to Dayton he could meet and talk with many persons who had witnessed flights. That didn’t satisfy Colonel Foster. He wrote again on November 29 that the War Office had had many descriptions of airplane flights by persons supposed to have witnessed them. What the War Office wanted, he said, was for him to see a flight.

The Wrights made it plain to the Colonel that they saw no point to making a demonstration of their machine unless negotiations had reached a point where a deal could be closed if the machine’s performance was as represented. They reminded him that it wasn’t necessary for the British War Office to put up any money in advance—only to sign an agreement that a deal would be closed after the Wrights had shown what their machine could do. Communications continued to pass between the Wrights and the British. Colonel Foster was succeeded as British military attaché at Washington by Colonel Gleichen and the latter made a trip to Dayton. But nothing came of the negotiations. In December, 1906, the British finally wrote to the Wrights that they had decided not to buy an airplane.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1906, the War Department at Washington heard once more about the Wrights in consequence of an exchange of letters between the Wrights and Godfrey Lowell Cabot, of Boston, who, it will be remembered, had written to them just after the Kitty Hawk flights in 1903. Cabot had seen a bulletin published by the Aero Club of America, on March 12, 1906, that told about the progress the Wrights had made during the season of 1905 at Huffman field. He had learned also, from his brother Samuel, a little about the Wrights’ offer to the U. S. War Department. Samuel Cabot got the news, presumably, from Chanute, with whom he from time to time exchanged letters. (He had written to Chanute asking if the Wrights needed any financial assistance for carrying on their experiments, and Chanute told him they did not.) Godfrey Cabot wrote to the brothers (in April, 1906) saying that he supposed they had offered their machine to the U. S. Army “with negative results,” but that if they ever decided to form a company to exploit the machine’s commercial possibilities, he wished they would send him a prospectus.

In their reply to Cabot (May 19), the Wrights confirmed the reports about their correspondence with the Ordnance Board. Cabot was so astounded over the treatment they had received that he promptly sent the facts to his relative, Henry Cabot Lodge, United States Senator from Massachusetts. Lodge forwarded Cabot’s letter, along with one of his own, to the Secretary of War—who sent it to the Board of Ordnance and Fortification. Brigadier General William Crozier, president of the Ordnance Board, wrote to Senator Lodge, on May 26, acknowledging his letter to the Secretary of War, and stating that “if those in control of the flying-machine invented by the Wright brothers will place themselves in communication with the Board of Ordnance and Fortification, War Department, Washington, D. C., any proposition they may have to make will be given consideration by the Board.”

Shortly afterward, Godfrey Cabot called upon General Crozier in Washington and showed him copies of the Aero Club Bulletin which told about the Wrights flying twenty-four miles in 1905. Since this was convincing evidence that the Wrights’ machine was capable of horizontal flight, General Crozier may have been somewhat embarrassed. He said the Ordnance Board would be glad to receive a proposition from the Wrights! He said, too, that he might send a representative to see the Wrights in Dayton.

In reply to a letter from Cabot reporting his talk with Crozier, the Wrights (on June 21) wrote:

If General Crozier should decide to send a representative to Dayton we would be glad to furnish him convincing proof that a machine has been produced which by actual operation has been shown to be able to produce horizontal flight and to carry an operator.

This letter also said:

We are ready to negotiate whenever the Board is ready, but as the former correspondence closed with a strong intimation that the Board did not wish to be bothered with our offers, we naturally have no intention of taking the initiative again.

General Crozier did not send any representative to Dayton.

Several months later, in November, 1906, newspapers got wind of the fact that there had been some kind of correspondence between the Wrights and the War Department. On November 29, many newspapers carried a dispatch from Washington which said: “While General Crozier will not discuss negotiations with the Wrights, he said today: ‘You may simply say it is now up to the Wright brothers to say whether the government shall take their invention. They know the government’s attitude and have its offer.’”

There had been no Government offer. The last communication the Wrights had received from the War Department was the one, more than a year before, in which the Ordnance Board said it did not wish to take any further action.

The Wrights felt sure that the War Department no longer doubted the existence of a successful flying-machine. It appeared, though, that certain Army officers still were unwilling frankly to admit their blundering behavior and come down from their high horse. There was reason to believe that the Ordnance Board would welcome a face-saving opportunity and hoped the Wrights would once again take the initiative by making a new proposal. But the Wrights were not ready to do so. Their advances had too often been spurned. The next move, they thought, should come from the War Department.

In that frame of mind, early in the spring of 1907, the inventors evolved a plan for bringing their machine to the attention of the War Department in a manner quite dramatic.

An exposition was going to be held on the Virginia coast that year to celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of the first English colony, at Jamestown. In connection with this Jamestown Exposition there would be a great naval review, April 26, at Hampton Roads. President Theodore Roosevelt and other important government people, including Army and Navy officers, would be present. What would be the matter, the Wrights asked themselves, with appearing there unexpectedly in their flying-machine? They could equip their machine with hydroplanes and pontoons for starting and landing on water, take it to Kitty Hawk, and then fly it, over Currituck Sound and beyond, to the scene of the naval review. After circling a few hundred feet above the battleships, the machine would disappear as suddenly and as mysteriously as it had come. No newspaper people or anyone else would know where it came from or how to get in touch with those who knew about it, and the mystery would grow. Officers of the Army and Navy would be asked embarrassing questions. Had they arranged for the flying-machine to appear, and had it been adopted for use in time of war? Those who still “knew” there was no practical flying-machine would be set to wondering.

The Wrights had many a quiet chuckle at the thought of the effect of their practical joke if it could be carried out. It was not too dangerous a project. Much of the flight could be made over shallow water in Currituck Sound. It would easily be possible to fly as far as the scene of the naval review and out of sight on the return trip before coming down.

They put an engine, with propellers attached to it, on pontoons, and placed this experimental outfit on the river at Dayton for preliminary trials. After a day or so of these tests it was evident that the plan of mounting their machine on hydroplanes and pontoons and taking off from the water was practical. But the inventors took aboard a passenger who tried to be helpful. In his efforts to throw his weight where he thought it would help the balance, he succeeded only in tilting the machine so steeply that it dived below the surface. The propellers were damaged. Before repairs could be made, something broke the dam in the river. The Wrights had to abandon their plans for a prank that might have been a national sensation.

Only a short time after the Wrights were planning their surprise flight, in that spring of 1907, Herbert Parsons, a member of Congress from New York, sent to President Roosevelt a clipping from the Scientific American—whose editor now knew about the Wrights. Roosevelt sent the clipping, with a note signed by his secretary, to Secretary of War Taft. The note suggested a talk with Representative Parsons to discuss the idea of experimenting with the Wright flying-machine. Taft sent the clipping and White House note to the Ordnance Board, with a note signed by his own secretary and headed “Endorsement.”

The personnel of the Ordnance Board had changed, at least partly, since the earlier correspondence with the Wrights. But the same attitude of aloofness regarding flying-machines still existed. The Board could not, however, ignore a letter from the office of the President of the United States, Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, with an endorsement from the Secretary of War. It might have been expected that the Board members would feel bound to investigate the reported flying-machine. But they couldn’t bring themselves to go that far. All they did was to send, on May 11, a brief letter to the Wrights, signed by Major Samson M. Fuller, Recorder of the Board. The letter said:

I am directed by the President of the Board to enclose copies of two letters referring to your aeroplane, for your information, and to say that the Board has before it several propositions for the construction and test of aeroplanes, and if you desire to take any action in the matter, will be glad to hear from you on the subject.

Accompanying the letter were copies of the notes from the White House and the office of the Secretary of War. The Wrights believed they knew why those copies were sent. It was to let them know that the Ordnance Board was writing only because of orders from higher up.

Though the letter from the Board was standoffish enough, yet it did not imply, as some of the earlier letters did, that the Wrights were a pair of beggars, or cranks, seeking funds. The Wrights thought the letter had been forced and that it really was a mere gesture, but nevertheless they treated it as if the Ordnance Board might now be seriously interested.

In their reply, May 17, the Wrights said they had some flying machines under construction and would be glad to make a formal proposal to sell one or more of them to the Government if the War Department was interested. They said the machine would carry two men and a supply of fuel for a flight of 200 kilometers; that a trial flight of at least 50 kilometers, at a speed not less than 50 kilometers an hour, would be made before representatives of the Government before any part of the purchase price was paid. They suggested a conference for the purpose of discussing the matter in detail. And they said they were willing to submit a formal proposition, if that was preferred.

In the next letter from the Ordnance Board, dated May 22, 1907, nothing was said about the Wrights’ suggestion for a conference; but the Wrights were requested to make a formal proposal incorporating the specifications and conditions contained in their letter to the Board, dated May 17.

The Wrights sent a formal proposal on May 31. In this proposal they repeated all the specifications and conditions mentioned in their letter of the 17th, and in addition agreed to the following: to teach an operator to fly the machine; to return to the starting point in the 50 kilometer test flight; and to land without any damage that would prevent the machine being started immediately upon another flight. The price stated was $100,000 for the first machine; others to be furnished at a reasonable margin above the cost of manufacture. They added that they were willing to make the contract speed 40 miles an hour, provided an additional sum would be allowed for each mile in excess of that speed in the trial flight, with a forfeit of an equal amount for every mile below. Again the Wrights made it plain that nothing was to be paid to them until after a trial flight had met all contract requirements.

The next letter from the Ordnance Board dated June 8 said that $100,000 was more than the Board had available, and that such an amount could not be obtained without a special appropriation by Congress at its next session. Then the letter went on to ask what the price would include; whether the United States would be granted exclusive use, or whether the Wrights contemplated commercial exploitation of their machine, or negotiations with foreign governments.

The Wrights wrote in reply explaining just what was included in the price. They said it did not include any period during which the use of the invention would belong exclusively to the United States, since a recent contract precluded such an offer, and that it was their intention to furnish machines for military use before entering the commercial field. The letter repeated what the Wrights had said before, that when a contract had been signed they would produce a machine at their own expense and make flights as specified in the contract in the presence of representatives of the War Department before any money whatever was paid to them.

That was the last letter to pass between the Ordnance Board and the Wrights for some time. But while the Wrights were in Europe, the Board undoubtedly began to hear from military attachés and others about the brothers’ negotiations abroad. At any rate, the Board began to show signs of uneasiness and they wrote a letter, signed by Major Fuller, October 5—received by the Wrights in Europe—to say that the Wright proposal of June 15 had again been given consideration by the Board at its meeting of October 3, 1907, but that nothing definite could be done before a meeting of Congress, as Congressional action would be necessary to accept the proposition, since the funds at the Board’s disposal were insufficient.

The Wrights’ reply, from London, on October 30, made it clear that if the price was the only thing in the way, that could probably be satisfactorily adjusted.

Wilbur Wright started home from Europe ahead of Orville, but before he left, it was agreed between the brothers that their price for an airplane to the United States Government would be $25,000.