XI

EUROPE DISCOVERS THE WRIGHTS

THOUGH the importance of the Wrights’ achievements was unrecognized in the United States until long after their first power flights, reports about their gliding prior to those flights had aroused much interest abroad.

In the spring of 1903, the Wrights’ Chicago friend, Octave Chanute, had gone to his native France in the interest of the St. Louis Exposition to be held the next year. One purpose of his visit was to arrange with Alberto Santos-Dumont, the Brazilian aeronaut, who lived in Paris, to make flights at St. Louis with his dirigible balloon. While in Paris, Chanute was invited by the Aéro Club to give a talk regarding aviation in the United States. In this talk, on April 2, he told of his own gliding experiments in 1896 and of those of the Wright Brothers in 1901 and 1902, illustrated by photographs. Then in the August, 1903, issue of L’Aérophile Chanute published an article on the same subject, with photographic illustrations, scale drawings, and structural details of the Wright 1902 glider. In the Revue des Sciences of November, 1903, he again published photographs and description of that machine. This 1902 glider far surpassed any that had ever been built before, and in it the problem of equilibrium had practically been solved. That glider was the basis of the specifications in the Wright patent. Chanute’s revelations therefore were sensational. And they did not fall on deaf ears.

Until this time, about the only man in France who was showing any interest in aviation was Captain Louis Ferdinand Ferber of the French army, who himself had made gliding experiments as a hobby while serving in an Alpine artillery corps. As early as 1901 he had begun an exchange of letters with Chanute, after having read in the Illustrierte Aeronautische Mitteilungen, a German magazine devoted mainly to ballooning, a brief article, supplied by Wilbur Wright, about the 1900 experiments at Kitty Hawk. A little later he wrote for information to the Wrights themselves. But now after the Chanute speech, Ferber was no longer alone among Frenchmen in thinking the Wrights’ experiments might be significant. Though belief in the possibility of a successful flying machine had been at lowest ebb in France, the information now made available by Chanute caused a greatly revived interest. Heretofore the Aéro Club had devoted its attention almost entirely to balloons and dirigibles, but it considered the French as leaders in every line pertaining to aeronautics. Immediately following the Chanute address telling of the Wrights’ gliding experiments in America, several members of the Aéro Club, led by Ernest Archdeacon, decided to organize a special committee on aviation. Archdeacon also made a warm appeal in favor of organizing contests for gliders to show that the French did not intend to allow anyone to surpass them in any branch of aeronautics. He subscribed three thousand francs for the organization of such contests and for prizes. L’Aérophile, official organ of the Club, which up to this time had published little about aviation, now suddenly began to carry many articles and items of news concerning projected experiments in gliding.

But it was some months before the French actually passed from the “talking” to the “doing” stage in gliding. In the meantime a brief dispatch about the Wrights’ power flights on December 17, 1903, had appeared in French and other European daily papers. Though the reports of these power flights were received with considerable skepticism, nevertheless they created such a furore in French aeronautical circles that before the end of January, 1904, no less than six gliders of the Wright 1902 type were being built in France from data furnished by Chanute.

Ernest Archdeacon, of the Aéro Club, placed an order with M. Dargent, a model maker of Chalais-Meudon, to build a copy of the Wright 1902 glider. Early in 1904 (January 28), Captain Ferber delivered a lecture at Lyon on the subject of gliding experiments, and a young man named Gabriel Voisin, just finishing his course in a technical school, came to him to ask advice about how to get into the field of aviation. He said he wished to “consecrate his life” to aviation. Ferber suggested that he should go to see Archdeacon. Voisin did so, and Archdeacon employed him to test the glider built by Dargent. Ferber gave Voisin his instructions in gliding. Then Archdeacon employed Voisin to build still another glider like the Wright machine. That contact with Archdeacon gave Voisin his start toward becoming a famous airplane manufacturer. And it was from that glider “du type de Wright,” as the French papers called it, tested by Voisin, that grew the first Voisin machines, soon to be followed by those of other copyists. Here was the real beginning of French—indeed of European—aviation.

Articles about the Wright power flights were appearing in the French, English and German aeronautical magazines. A longer article about the Kitty Hawk event was printed in the March, 1904, issue of Illustrierte Aeronautische Mitteilungen from Carl Dienstbach,7 a musician in New York, who as a side line was the magazine’s correspondent.

One copyist after another began to use devices and technical knowledge invented or discovered by the Wrights. When Ferber received a letter from the American publication, the Scientific American, asking for an account of his own gliding experiments, he wrote to them that he was simply a “disciple of the Wright Brothers.” But these copyists were not content to follow the Chanute revelations and build gliders just like that of the Wrights. Instead, they tried to improve upon the Wrights’ work. The “improvements” were not successful, because the builders did not have the Wrights’ knowledge and wind-tunnel data, except that used in the 1902 glider, to guide them. So great were their difficulties that some of the experimenters began to place blame on Chanute. They thought Chanute must have misrepresented what the Wrights had done—maybe purposely. That was the only way they could account for their failure to get the good results obtained by the Wrights.

Robert Esnault-Pelterie, a member of the Aéro Club, pointed out that they had not put to a fair test the information on the Wright glider that Chanute had given them, because, he said, in building their gliders they had not strictly adhered to Chanute’s description and specifications. Since they had all the data needed to reproduce the glider that Chanute had reported as having been so successful, Esnault-Pelterie said, the way to determine the value of the information was to build a Wright glider exactly like Chanute had described and then test it to see how it performed. He himself then built such a machine, in 1904, and reported that he got the same performance as had the Wrights.

While the French were carrying on these experiments with copies of the 1902 Wright glider, the Wrights themselves were busy with their power machine with which they made more than 100 starts in 1904. It was not until late October, 1906, or nearly three years after the Wrights’ first power flights, that a French power machine was flown. (This machine, piloted by Santos-Dumont, was reported to have made a hop of 200 feet, about ten feet above the ground.)

Before long, Archdeacon and another member of the Aéro Club, Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, were offering aviation prizes, and doing all they could to encourage someone to try to build a successful power plane. But as Captain Ferber later made clear to Georges Besançon, editor of L’Aérophile, in a letter Besançon published in his issue of June, 1907, this revival of interest in aviation in France, and whatever was accomplished, was all a direct outgrowth of information about what the Wrights had done in America.

In October, 1905, reports about the long flights accomplished that year by the Wrights with their power machine were received in France. They created an even greater stir in French aeronautical circles than had the earlier reports. Just at the time these reports reached France an organization was formed there to be known as the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the purpose of which was to verify and record the truth about reported aeronautical flights. The Aero Club of America, formed at about the same time, was made the official representative of the F.A.I. in America. No flight had as yet been made in France with a motor plane. Long afterward, many uninformed persons, even in the United States, declared that the flights by the Wrights prior to 1908 really should not count, as they had not been officially witnessed by any representative of the F.A.I.—the organization that came into being after the flights had been made!

As the tempo of interest increased, the Wrights were kept fairly busy writing letters to France in reply to requests for information. At the time of the first reports of the 1903 flights at Kitty Hawk, probably the only person in France inclined to believe them was Captain Ferber. Knowing what he did, from correspondence with Chanute, and with the Wrights themselves, he was not too incredulous. If he had said at first that he believed human flight might have occurred, he doubtless would have been laughed at—especially by those who had been most busily experimenting. But as early as May, 1905, Captain Ferber had written to the Wrights, asking if they would sell a power plane and at what price. They were not ready to discuss such a project at that time and, though Ferber wrote a second letter prodding them, they did not reply until October 9, four days after they had completed their most important flying experiments for that year.

In that letter, after telling of their recent long flights, the Wrights said they were prepared to furnish machines on contract, to be accepted only after trial trips of at least forty kilometers, the machine to carry an operator and enough supplies of fuel for a flight of 160 kilometers. They said they would be willing to make contracts in which the minimum distance of the trial trip would be more than forty kilometers, but that the price of the machine would then be greater. They were also ready, the letter added, to build machines carrying more than one man. No figures as to price were given.

Hoping to have the French War Department buy a plane, Ferber went to his chief, Colonel Bertrand, director of the laboratory of research pertaining to military aeronautics. But Colonel Bertrand told him the French Government could not commit itself to pay a sum “probably enormous” for an invention not yet authenticated. All that it was possible to do, said Bertrand, was to appoint and send a commission to see the Wrights.

Again Ferber wrote to the Wrights, on October 21, asking what the price for a machine would be. He said he didn’t think his government would any longer be interested in paying so great a sum as it had been when he had first asked for a price.

The Wrights replied, on November 4, saying they would consent to reduce their price to the French Government to one million francs—$200,000—the money to be paid only after the genuine value of their discoveries had been demonstrated by a flight of one of their machines in the presence of French Government representatives. Ferber had not told in his letter what the French Government had been willing to pay and the Wrights did not say what the price of one million francs was reduced from! The price was to include a complete machine, and instruction in the Wright discoveries relating to the scientific principles of the art; formulas for the designing of machines of other sizes and speeds; and personal instruction of operators in the use of the machine.

At the time Captain Ferber was thus dickering for the possible purchase of a Wright flying-machine, others in France who were interested in aeronautics still doubted if such a machine existed.

About the middle of October, Frank S. Lahm, a member of the Aéro Club of France, had a chance meeting with his friend Patrick Y. Alexander, of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, who had visited the Wrights as recently as the previous April. Alexander expressed to Lahm his strong belief that the Wrights had actually been making power flights in America.

Lahm was an American. After going to France from Mansfield, Ohio, many years before, he had introduced the Remington typewriter to Europe. As a hobby he had taken up ballooning and held a pilot’s license. It was of more than casual interest to him that Alexander believed successful flights had been made in America. Lahm then made an effort to learn the facts from a source right in Dayton, Ohio. He wrote to Nelson Bierce, a manufacturer there whom he knew, asking what sort of people the Wrights were and what was known about their reported experiments. Bierce didn’t make any investigation, but wrote to Lahm, late in November, that the Wrights were considered men of good character, and that they were said to be carrying on some kind of flying experiments near Dayton; but, he said, no one seemed to know much about the nature of these experiments.

Before there was time for Bierce’s letter to reach him, Lahm got other news about the Wrights. A letter they had sent on November 17, to Besançon, editor of L’Aérophile, giving a detailed account of their most recent experiments, had been published on November 30 in L’Auto, a Paris daily dealing with sports. Besançon had given the letter to L’Auto because his own next monthly issue would not go to press for a week or more and he was afraid a rival German publication might print, before he could, similar information from the Wrights.

That letter to Besançon, containing much specific information, created a sensation. There was much animated talk about its contents that night of November 30 at the Aéro Club. Indeed, that date is noteworthy in aeronautical history, for publication of the letter to Besançon led to several important investigations.

News about the Wrights’ recent flights that the letter revealed was taken up by one or two of the wire services and cabled back to the United States where it reached various newspapers, including those in Dayton. But Dayton editors couldn’t understand why the Wrights should have stirred up so much excitement in France.

One investigation was started by Lahm, now determined to get the facts. He had a brother-in-law in Mansfield, Ohio, Henry M. Weaver (a manufacturer of cash carriers for department stores); and Weaver had a son, Henry, Jr., perhaps not too busy to go to Dayton and find out all about the Wrights. Immediately after leaving his friends at the Aéro Club, Lahm sent this cable to the younger Weaver: “Verify what Wright brothers claim necessary go Dayton today prompt answer cable.”

The young man in Mansfield, never having heard of the Wrights, supposed the message must be for his father, then away on a business trip, and he forwarded it to him at the Grand Pacific Hotel in Chicago. It was received by the father on December 1, shortly after he had retired for the night. Weaver, Sr., didn’t at once recall ever having heard of the Wrights, but if they had a “claim” against his brother-in-law, he would see what could be done about settling it. As the question must be important he sent a wire to Dayton that very night. Having no street address for them, he addressed it simply to “Wright Brothers.” This message was not clear to the Wrights and their reply the next morning was as puzzling to Weaver as his had been to them. To get down to dots and make sure he was addressing the people he sought, Weaver then sent another telegram asking the Wrights if they knew F. S. Lahm, of Paris. The Wrights didn’t know Lahm but they knew of him and replied: “Yes Lahm French aeronaut.” When he noted that word “aeronaut,” Weaver began to remember vaguely having heard some years previously about two brothers who had experimented with a glider somewhere in the Carolinas. The mystery seemed to be lifting. Doubtless the Wrights had made a glider for Lahm and now there was some misunderstanding about the price. He immediately telegraphed again to the Wrights, saying he would arrive in Dayton the next morning (Sunday), and asking the Wrights to meet him at the Algonquin Hotel.

When he reached the hotel in Dayton, Weaver discovered that there was no firm of Wright Brothers in the telephone book or city directory. The hotel clerk had never heard of them. Others whom he asked if they knew of anyone in Dayton having a flying-machine looked at him blankly and shook their heads. Well, these Wrights must be somewhere, Weaver reflected, for they had replied to his two earlier telegrams. He may have feared that their place of business was closed for the week end before they could have received his telegram asking them to meet him. At any rate, he went to the office of the telegraph company. There he met the messenger boy who had delivered his message. The boy explained that the brothers had their office at the Wright Cycle Company but that, since it was Sunday, they could not be reached except at their home. Weaver then returned to his hotel. There he found Orville Wright waiting for him.

As soon as they began to talk, Weaver said: “You made a glider, I believe, for Mr. Lahm, in Paris.”

Orville, of course, shook his head. No, he said, they had never made a glider for Mr. Lahm.

“Then,” asked Weaver, even more puzzled, “what in the world can be the meaning of this cable?” And he handed to Orville the message from Paris.

Orville then understood. Evidently, he said, Lahm, a member of the Aéro Club of France, wished to find out if the report of their flights sent to the Aéro Club by the Wright brothers was true.

As Weaver later reported in a letter to Lahm, he was already impressed by this younger Wright brother. “His very appearance would disarm any suspicion—with a face more of a poet than an inventor or promoter. In contour, head and face resemble Edgar Allan Poe ... very modest in alluding to the marvels they have accomplished ...”

Orville, somewhat amused, said if an investigation was desired, they might as well get right at it. It was too late in the season for flying, and the machine had been taken apart, but he could introduce the visitor to many responsible people who had seen them fly.

Orville took him to the home of C. S. Billman, of the West Side Savings and Loan Company. The Billmans were a fairly large family and nearly all had seen the Wrights fly. When the callers were taken into the sitting-room the first member of the family to appear was a four-year-old boy. “Son,” asked Weaver jokingly, “have you ever seen a flying-machine?” He wasn’t expecting to get evidence just yet; but the boy began to run around the room, trying to imitate with his hands the motion of a propeller and to make a noise like the machine.

Turning to Orville, Weaver laughingly observed: “I’m about convinced already. That boy couldn’t be a bribed witness.”

They also went, by interurban car, to talk with the Beard family, across from the flying field, and with Amos Stauffer, the nearest farmer up the road.

As Weaver reported: “On October 5, he [Stauffer] was cutting corn in the next field east, which is higher ground. When he noticed the aeroplane had started on its flight he remarked to his helper: ‘Well, the boys are at it again,’ and kept on cutting corn, at the same time keeping an eye on the great white form rushing about its course. ‘I just kept on shocking corn,’ he continued, ‘until I got down to the fence, and the durned thing was still going round. I thought it would never stop.’ I asked him how long he thought the flight continued, and he replied it seemed to him it was in the air for half an hour.”

Then Orville and Weaver returned to Dayton and called on William Fouts, West Side druggist, who had witnessed the long flight on October 5.

Later they went to the Wright home. Of that visit Weaver wrote: “The elder brother, Wilbur, I found even quieter and less demonstrative than the younger. He looked the scholar and recluse. Neither is married. As Mr. Wright expressed it, they had not the means to support ‘a wife and a flying-machine too.’”

Weaver was completely convinced before he left Dayton, and on December 3, cabled to Lahm: “Claims completely verified.” A few days later, on December 6, back at his home in Mansfield, he rushed a letter to Lahm giving his evidence of what the Wrights had done.

In a little more than a week after Weaver’s visit to Dayton, another investigator appeared there, Robert Coquelle, representing L’Auto, of Paris. He had been in New York attending the six-day bicycle races and arrived in Dayton on December 12. Since his paper and Les Sports had taken opposite sides regarding the possibility that the Wrights had flown, and L’Auto had been pro-Wright, Coquelle wished to report on these “deux marchands de cycles” in a way to make a sensation. The imaginative tale he wrote about how “mysterious” were the Wrights was almost worthy of his compatriot, Dumas. The Wrights gave him names of people who had witnessed flights but it is believed he didn’t bother to consult many of them, evidently feeling sure he could invent a better story than they could tell him. However, Coquelle was convinced that the reports about the Wrights’ flights were not exaggerated and he cabled a preliminary dispatch to his paper: Wright brothers refuse to show their machine but I have seen some witnesses it is impossible to doubt.

On December 13, the day after Coquelle’s visit to Dayton, the Wrights sent another letter to M. Besançon, editor of L’Aérophile, in reply to questions of his, and gave him details of their recent flights, distances, height at which they flew, size of field, and so on. Incidentally the closing paragraph of that letter contained a statement in contradiction of a myth, still widely accepted:

The claim often made in the 19th century that the lack of sufficiently light motors alone prohibited man from the empire of the air was quite unfounded. At the speeds which birds usually employ, a well-designed flyer can in actual practice sustain a gross weight of 30 kilograms for each horsepower of the motor, which gives ample margin for such motors as might easily have been built 50 years ago.

Before Besançon could have received this letter, with its details of recent flights, Robert Coquelle arrived in Paris, having taken a boat from New York only a day or two after his stay in Dayton, and his sensational story was published. Much of this report seemed so incredible that one member of the Aéro Club said it almost made him wonder if the Wright brothers existed at all.

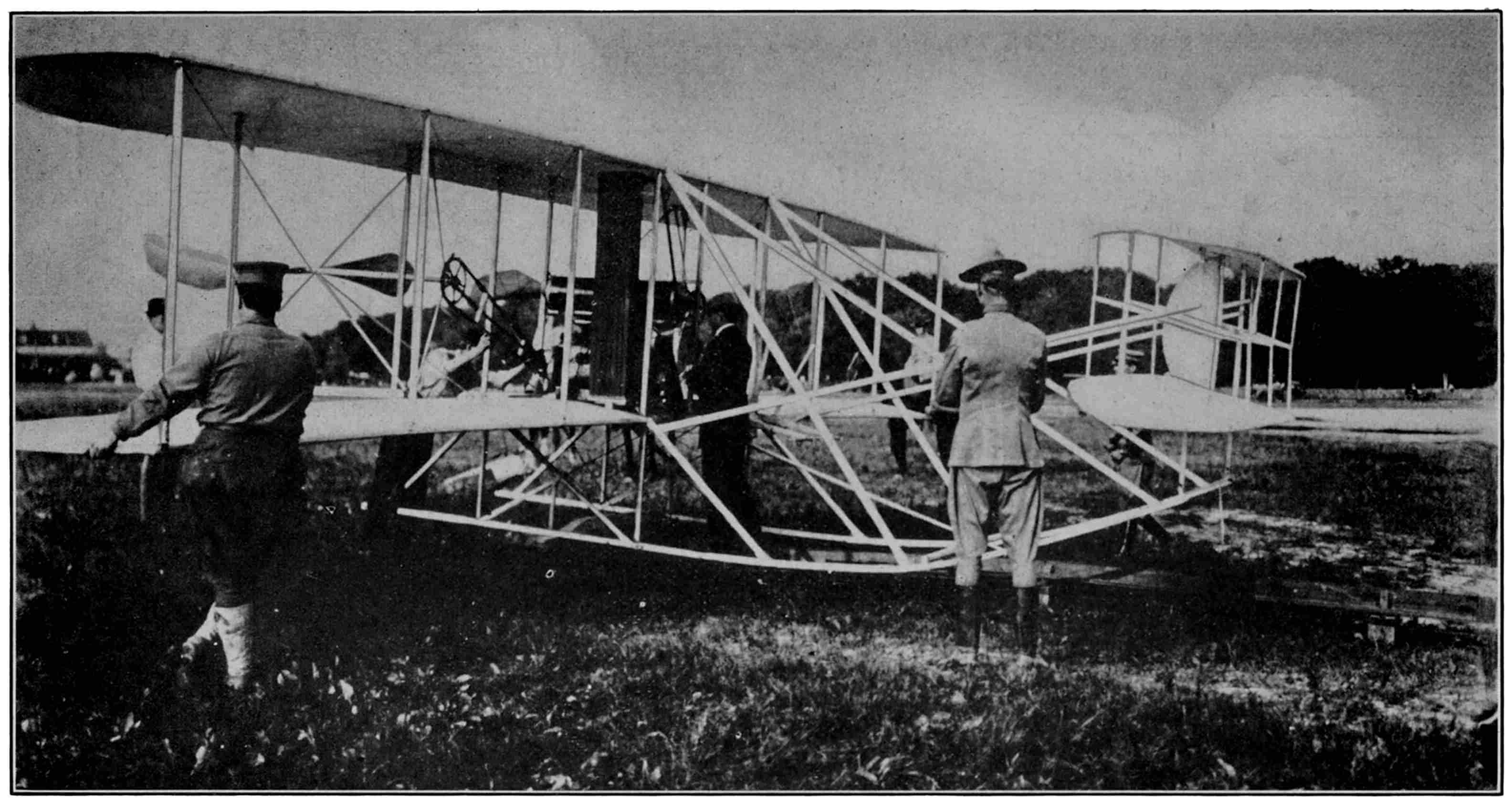

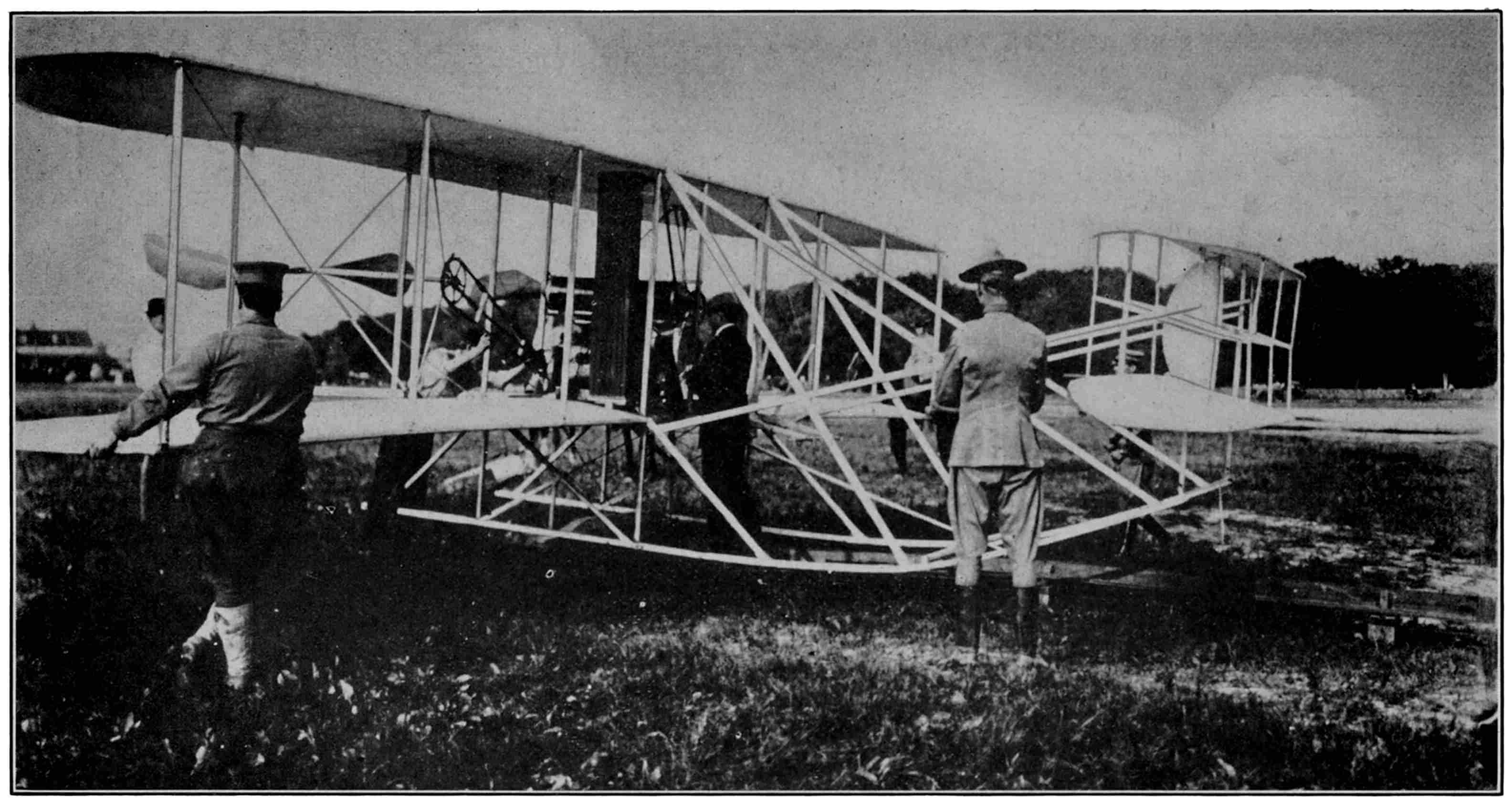

THE U. S. ARMY TEST. Preparing the Wright plane for a test at Fort Myer.

What Weaver had written in his letter seemed convincing enough to Lahm and he prepared a French translation of it to read to the aviation committee of the Aéro Club of France at a meeting on the night of December 29, 1905. That meeting, as Lahm later told about it to friends, and in an article he gave to the Mansfield (Ohio) News, published October 24, 1908, was a memorable one. The skeptical members of the committee, greatly in the majority, having heard of Weaver’s telegram, assumed the more elaborate report would be favorable to the Wrights, and were prepared to combat it. Characteristic of the French, there was almost ceremonious politeness at the beginning of the meeting because everyone supposed there might be less politeness as the discussions went on.

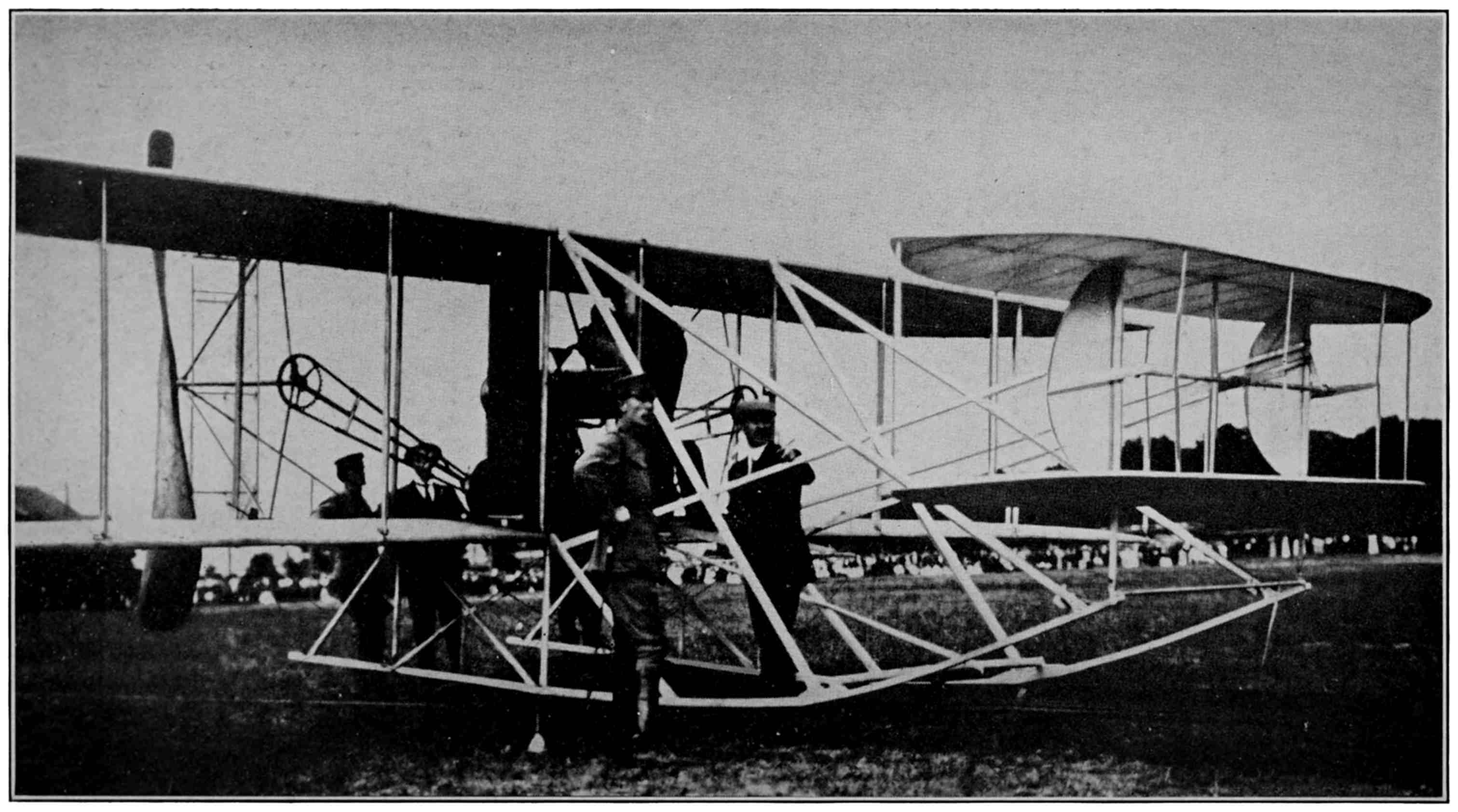

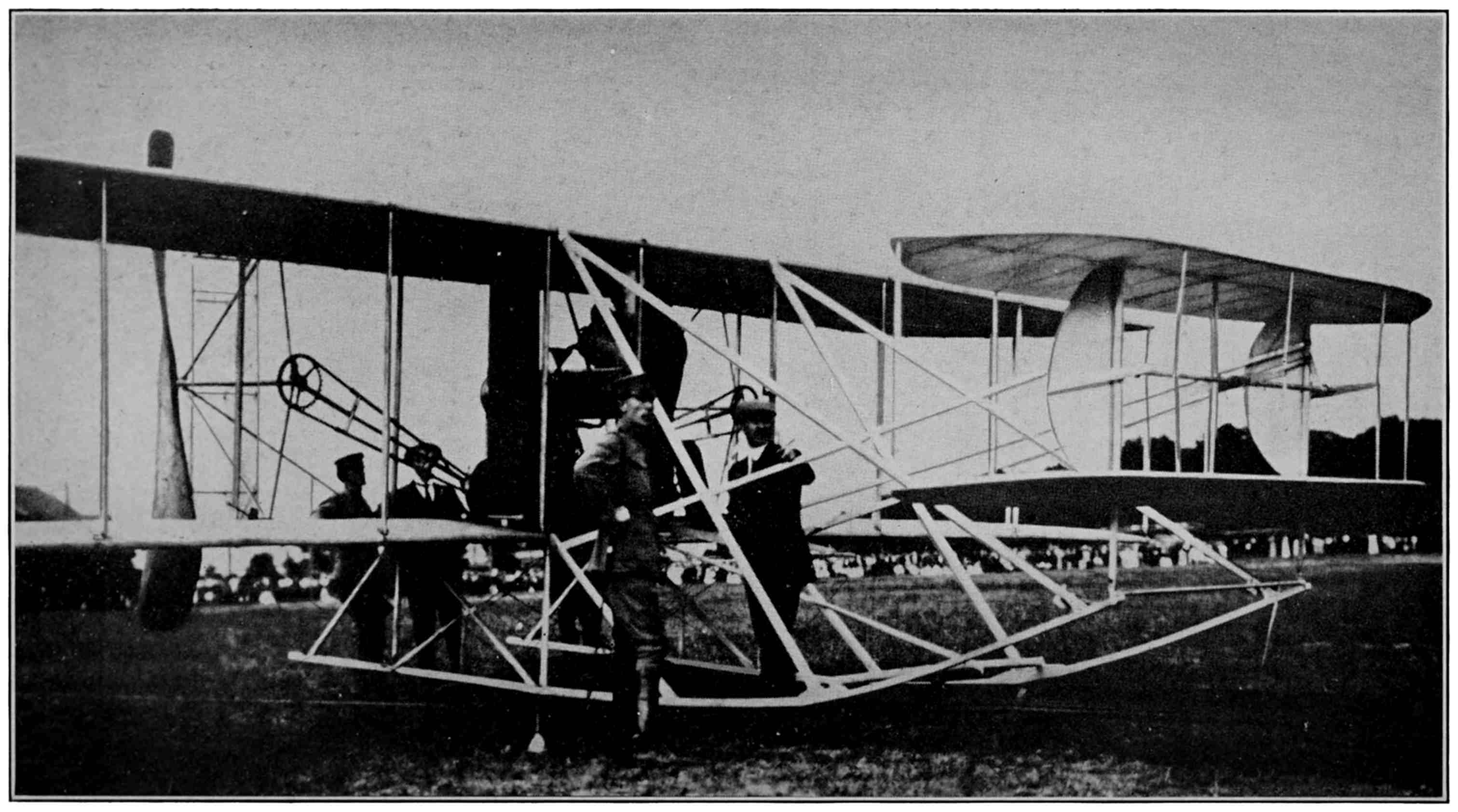

AT FORT MYER. Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm and Orville Wright with the Wright plane during the test at Fort Myer. Lieutenant Lahm was the first army officer to fly as a passenger in a plane.

By the time Lahm had finished reading the letter, everyone began to talk at once. Archdeacon, who presided, was famous for a high-pitched staccato voice and it could be heard calling for order as he also rapped on the table before him with a flat metal ruler.

One member observed that they had seen nothing about the Wrights’ flights in American newspapers, recognized as enterprising. He found himself incapable of believing, he said, that all the journalists in America would permit so important a piece of news to escape them.

Another remarked that they had heard the Wright brothers were of modest enough wealth. Who, he asked, is their financier? It would be interesting to talk with him.

Lahm was hard put to it to explain the lack of news about the flights in the American papers. He himself didn’t understand that. But he tried to explain that since the brothers did most of the mechanical work on their machine themselves they did not require financial assistance. His voice, however, was drowned in the hubbub. As the discussion continued, so vehement were the contradictions of the Weaver letter that Lahm, Ferber, Besançon, and Coquelle, the only ones present who seemed to believe it, hardly dared express themselves at all. Someone turned to Coquelle and asked him if he really accepted the stories of the Wrights’ flights.

“I do,” he said—but in a low voice.

All conceded that Lahm’s friend Weaver had doubtless been sincere in what he wrote but they insisted that he had somehow been fooled. They “knew” flight was impossible with a motor of only twelve horsepower. Indeed, many had decided that power flight would always be an impossibility. This belief was all the stronger because a number present had personally done enough in attempts to fly to know the difficulties.

One member after another strolled into an adjoining room where they could argue without being called to order. Finally Archdeacon found himself nearly alone. When, long after midnight, the meeting finally broke up the one thing all were agreed upon was that human flight, if true, was of vast consequence.

When the Wrights learned how great was the incredulity at the Aéro Club in France they were only amused that the stories seemed to the French too wonderful to be true.

On December 31 the Weaver letter to Lahm was published in full in L’Auto. The next day it appeared in the Paris edition of the New York Herald and also in Les Sports, competitor of L’Auto.

Though the Aéro Club did not yet know it, Captain Ferber in November had started still another investigation. He had written to the Wrights on November 15, asking permission to send an “official” commission to see them. The Wrights answered on December 5 that they thought it highly advisable that the French Government send a commission to make a thorough investigation of their claims, and that it should be done at once. Eight days later the Wrights received a cable from Ferber saying: “Friend with full powers for stating terms of contract will sail next Saturday.” Ferber also sent a letter, a copy of which, he said, would be carried by Arnold Fordyce as his means of identification, but this letter did not reach the Wrights until after the visitor had arrived. As Ferber only a few weeks before had asked permission to send a military commission, the brothers supposed the man en route to Dayton represented the War Ministry.

Arnold Fordyce, the French emissary, arrived in New York on the Lorraine, and reached Dayton shortly after Christmas, 1905. He was about thirty-five years old, formerly an actor, of characteristic French politeness, and he spoke English. His first meeting with the Wrights was in their office over the old bicycle shop.

To the Wrights’ surprise he told them, in reply to a question, that he had no connection with the French War Ministry. He had come, he said, on behalf of a syndicate of wealthy men who wished to buy a flying-machine and to present it to the French Government for the national defense. He said he was secretary to M. Letellier, member of the syndicate and owner and editor of the Paris newspaper, Le Journal. He went on to explain that Letellier and his associates in the syndicate were presenting the plane to the Government with the hope they might receive decorations of the Legion of Honor. His story seemed to the Wrights a bit fishy. They thought it more probable that he was really representing the French War Ministry, but that the War Ministry did not wish to appear directly in negotiations for a flying-machine. The Wrights went ahead, though, to give him the information he sought. First of all, he wished to make sure that they really had a machine that would fly. They arranged for him to meet a number of trustworthy persons who had witnessed flights, among them bankers, other prominent businessmen, and county officials.

Fordyce was soon convinced that the machine would do all that had been claimed for it, and he wanted a contract to take back with him to his principals. Though Ferber’s cable had stated that Fordyce was coming with “full powers” he did not have a power-of-attorney to represent his principals. Still believing that Fordyce’s true mission was in the interest of the French War Ministry, the Wrights had no objection to entering into a contract with him granting an option for a short period. They made it clear, however, that they reserved the right to deal with their own Government at any time, even though the United States War Department had not seemed appreciative of their former offers of exclusive rights to the aeroplane. They also made it clear that Letellier and his associates in the “syndicate” would have no rights whatever in the machine except the right to pay for it. The machine would be delivered only to the French Government.

The Fordyce option was for the purchase of one flying-machine at a price of 1,000,000 francs, or $200,000, the price the Wrights already had set in a letter to Captain Ferber. The option was to become void if the holder failed by February 5, 1906, to deposit in escrow with J. P. Morgan & Co., New York, 25,000 francs ($5,000) to the joint credit of the Wright brothers and Arnold Fordyce. It was provided that the contract would become null and void if the holder failed to make a further deposit in escrow with J. P. Morgan & Co. by April 5, 1906, to bring the total to 1,000,000 francs. But if the holder failed to deposit altogether 1,000,000 francs, as stipulated, then the first deposit of 25,000 francs would belong to the Wright brothers. If on the other hand the Wrights failed to carry out any part of their own obligations under the contract they would receive nothing.

On February 5, 1906, the date stated in the option for the first deposit, the Wrights received a telegram from Morgan, Harjes & Co., Paris, stating that 25,000 francs had been deposited with them in escrow to the joint credit of the Wright Brothers and Arnold Fordyce. This seemed to confirm the suspicion held by the Wrights that Fordyce represented the French Ministry of War and not a syndicate. But this suspicion later proved to be false.

Some time after the Wrights had given this option they heard an entirely different story about the nature of Fordyce’s mission. According to this story, Captain Ferber, unable to persuade his superior officers in the War Ministry to send an official investigator to Dayton, had hit on the idea of having an investigation made by a Paris newspaper. He then went to see Letellier, owner of Le Journal. Letellier saw the possibilities of prestige for his paper by being able to print the facts about the Wrights. If they really had flown, that would be of great interest, and if they were only “bluffers,” as many in France thought they were, the truth about them would still be worth publishing. Letellier could well have afforded the gamble of sending an investigator to Dayton. Aside from his ownership of Le Journal, he was a man of considerable wealth, having made his money as a contractor. He had built the main fortresses at Liège.

Whatever the truth may have been, if Letellier had intended to publish what Fordyce learned about the Wrights, he did not at once do so. He took the Fordyce option and presented it to the War Ministry and he received in return a letter from the Minister of War stating that if a Wright plane were acquired by the Ministry the purchase would be made through Le Journal. Thus Le Journal not only would have a big “scoop” on news of the purchase, but would receive credit and acclaim for a big patriotic act. Perhaps the owner of the paper would be decorated!

For some time war clouds had been gathering over Morocco and it looked as if there might be trouble between France and Germany. If war should come, a flying-machine for scouting purposes would be of great value. But in spite of the fact that a Frenchman, Fordyce, had been to see the Wrights and reported favorably about them, the French war chiefs couldn’t bring themselves to accept as a certainty the existence of a practical flying-machine. The story seemed too incredible. There must be a “catch” somewhere. Still, the War Ministry was willing to risk making the down payment of 25,000 francs.

But when M. Etienne sent the down payment of 25,000 francs to Morgan, Harjes & Co., the Paris branch of the banking firm of J. P. Morgan & Co., on the last day of the allotted time, he nearly lost the option, for an unexpected reason. Morgan, Harjes & Co. did not wish to accept the money. Though the bank was under American control, French procedure prevailed, and its officers were reluctant to hold money in escrow. They feared there might be a dispute as to whether it finally would belong to the War Ministry that deposited it, or to the Wrights. It required eight hours of perspiring persuasion on the part of a War Ministry representative before the bankers agreed to accept the money and the option became binding.

After the option was in force, but before the date set in the contract for the final payment, the French War Ministry sent a commission to Dayton for the purpose of obtaining some amendments to the contract, pertaining to the test flights.

This commission, which sailed from Cherbourg on the Saint Paul, was headed by Commandant Bonel, of the Army Engineer Corps. Another member was Arnold Fordyce. They reached New York on March 18, 1906. The other two members were Captain Fournier, military attaché of the French Embassy at Washington, and Walter V. R. Berry, an American subject, who was legal counselor to that embassy. Though Fordyce was by now zealously pro-Wright, the men at the War Ministry had no fear of his exerting too much influence on the others, because of the presence of Commandant Bonel, who was outspokenly skeptical. He had witnessed tests by the French Government of the unsuccessful machine designed by Clement Ader, a few years previously, and was convinced that no heavier-than-air machine had ever flown or ever could. Bonel would hardly let the commission make a fool of itself. Since he was the only one of the four who spoke no English, he would need to have everything explained to him—all the more reason why he would not be easily imposed upon.

Before the French quartet had been in Dayton long, however, Bonel was the most enthusiastic convert of all. The visitors met dependable witnesses of flights who had previously talked to Fordyce; and photographs of the machine in flight could hardly be fakes. Most of all, they were impressed by the obviously high character of the Wrights themselves. In cables to France they strongly recommended that the deal be closed.

But while the commission was still in Dayton, the European war crisis had subsided. Even before the formal settlement of the dispute, at the close of the conference at Algeciras, Spain, on April 7, it was known that France would still have a favored position in Morocco, and the need for a scouting plane by the French Army became less pressing. The War Ministry now began to demand more and more in airplane performance. They would cable asking if the plane could fly at an altitude of at least 1,000 feet; if the speed could be greater than hitherto mentioned. Then the next day there would be a request for greater weight-carrying capacity. The Wrights, slow as always to make rash promises, said frankly that they had never flown much higher than 100 feet, but that the plane could fly at much more than 1,000 feet, though they would probably need additional practice before making a demonstration. They could increase either the speed or the weight-carrying capacity, too; but it would not be easy to do both in the same machine—no more than one could produce a draft horse and a race horse in the same animal.

The demonstrations of the machine the Wrights agreed to make were already stiff enough, and if they failed on any one of them, within the allotted time, even if only on account of delay caused by accident, their contract would be broken; but they felt sure of what they could do and were willing to take the chance.

When the time limit for the deposit of the rest of the 1,000,000 francs with J. P. Morgan expired, on April 5, the commission was recalled. Before leaving Dayton the visitors expressed their own vexation over the rejection by the Paris officials of their recommendations.

The members of the commission still believed, though, that when Bonel and Fordyce were back in Paris and presented all the facts to the War Ministry, there would be an extension of time and the deal carried out. But it never was. The French Minister of War agreed, however, that the Wrights were entitled to receive the forfeit money of 25,000 francs held in escrow by J. P. Morgan & Co.

Before leaving Dayton, the Frenchmen said they believed they knew what was back of the failure to close the deal. They said frankly that it was probably the present attitude of Captain Ferber, the man who had been instrumental in starting the negotiations. Ferber, they thought, with the Moroccan question no longer pressing, had now decided that with his knowledge of the Wright plane he could build one himself, and so become the French pioneer in aviation—a greater honor than being merely the instrument of introducing the aeroplane into France.

During the time the Frenchmen were at their hotel in Dayton, it might have been expected that their presence would become known to local newspapermen and that the world would have learned of what was going on. To avoid attracting attention they had taken the precaution to avoid the Hotel Algonquin where Fordyce had stayed on his earlier visit, and were at the Beckel House. They were unmolested there until an employee of one of the telegraph offices “tipped off” a reporter friend. The telegrapher had noticed various cables in code going to France and felt sure the Frenchmen must be carrying on an important deal. A reporter nabbed Fordyce and Bonel one evening in the hotel lobby on their return from a theater. As Bonel spoke no English, Fordyce parried the reporter’s questions. He thought a plausible explanation of their presence would be that they were studying the water system of a typical American city. But what he said was that they were studying Dayton’s “water pipes.” That satisfied as well as amused the reporter and nothing about the French commission got into the papers.

The local newspapermen had failed to note that, after Fordyce’s previous visit, the New York Herald of January 4 had printed a brief item about his having seen the Wrights to discuss a contract. It never occurred to anyone in Dayton that the Wright brothers could have attracted visitors from across the Atlantic, for the Wrights still were not “news.” If the Frenchmen had made a statement that they were there dickering with the Wrights for a $200,000 contract, it is possible that the local papers would not have printed it. They might not have believed such a tale.

Only a few days after the French commission had left Dayton, another foreign visitor dropped in on the Wrights—the Englishman, Patrick Y. Alexander.

After some casual talk, he inquired with seeming innocence, as if just to make conversation: “Is the French commission still here?”

The Wrights were startled. So great had been the secrecy about the visit of the Frenchmen that not many even in the French Government were permitted to know about their trip to Dayton. How did this mysterious Britisher know about it? The Wrights assumed that he must have been a volunteer worker in the British secret service. It was now obvious that he had crossed the Atlantic for no other purpose than to call on the Wrights and had hoped to burst in upon them while the Frenchmen were still there. After a stay of only one day in Dayton he hastened back to New York to sail on the next boat. His call made it all the more clear that the British were then more interested in what other European governments were doing about planes than in acquiring an air fleet of their own.

Incredulity about the Wrights’ power flights continued at the Aéro Club and in newspaper circles in France. In November, 1906, the Wrights received a visitor in Dayton, Sherman Morse, representing the New York Herald. His introduction was a cabled message to his managing editor from the owner of the paper, James Gordon Bennett, in Paris. The message said: Send one of your best reporters to Dayton to get truth about Wright brothers’ reported flights.

The reporter got the truth and wrote intelligent articles that appeared in the New York Herald. These included reports of men who had witnessed flights. Parts of the Morse articles appeared in the Herald’s Paris edition on November 22 and 23. But evidently those in charge of the Paris Herald still were not convinced by the reports from Dayton by their own man. On November 28, the Paris Herald had an editorial about the Wrights which included the statement that in Europe curiosity about their machine was “clouded with skepticism owing to the fact that information regarding the invention is so small while the results which its inventors claim to have achieved are so colossal.” And the next day, the Paris Herald gave space to a news item in which Santos-Dumont was reported as saying that he “did not find any evidence of their [the Wrights] having done anything at all.”

Late in 1906, Frank S. Lahm, who had cabled his brother-in-law, Weaver, to make an investigation, was in the United States, and he, accompanied by Weaver, went on November 22 to see the Wrights in Dayton. He was convinced, of course, that their statements could be relied upon, but he made further investigation of his own, interviewing witnesses not previously seen by Weaver. After his return to Paris, he prepared a long letter to the Paris Herald, in which he expressed his belief in the reported flights. The newspaper devoted a column to the Lahm letter on February 10, 1907. But having distrusted what their own representative had written, it was not to be expected that the editors would give full belief to what Lahm now told them. In the same issue as his letter, was an editorial headed “Flyers or Liars.” “The Wrights have flown or they have not flown,” the paper profoundly stated. “They possess a machine or they do not possess one. They are in fact either flyers or liars.... It is difficult to fly; it is easy to say ‘we have flown.’”