6 Value creation maps

(Written by Marco Montemari, Assistant professor, PhD and Christian Nielsen, Associate professor, PhD)

[Please quote this chapter as: Montemari, M. & C. Nielsen (2012), Value creation maps, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon.com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

The problem – as well as the prospect – with business models is that they are concerned with being different; the business needs a unique selling point. So the bundle of indicators on strategy, intellectual capital, and so on that will be relevant to analysis or disclosure will differ from firm to firm. The information needs to be communicated – in the strategic context of the firm, as this would show its relevance to the value creation process in the company. It does not make sense to insert such information into a standardized accounting regime. We would point out that if it is difficult for the company itself to conceptualize the business model, then it will probably be even more difficult for external parties to analyze it. At present there exists very little literature on the different aspects of analyzing business models.

When we perceive relationships and linkages, they more often than not reflect some kind of tangible transactions, i.e. the flow of products, services or money. When perceiving and analyzing the value transactions going on inside an organization, or between an organization and its partners, there is a marked tendency to neglect or forget the often parallel intangible transactions and interrelations that are also involved.

So, to create a more meaningful analysis and understanding of a business model, we need to assemble a new cocktail of tools including, as essential ingredients, intangible transactions and relationships. Although our work has so far been primarily focused on network-based business models, the conclusions seem easily generalizable to other settings.

We have found it useful to integrate the generic tangible and intangible transactions from the value network mapping perspective of Verna Allee (2011) with the notions of cognitive maps, and final y to place these aspects in the strategic notions of the Intellectual Capital Guideline (Mouritsen et al. 2003a) and the Analytical Model (Mouritsen et al. 2003b). In union, these ideas materialize into the value creation map!

6.1 What is the value creation process?

Value creation is now the main aim of any company. Creating value means to generate economic wealth, that is, to obtain a performance improvement in terms of increased sales or decreased costs.The value creation process depends on the combination of value drivers considered important by the company. A value driver can take two forms. It can be a tangible resource (e.g. machinery) or an intangible resource (e.g. trademarks, employees’ competences) available to the company. It can also be a critical success factor considered important by customers and that the company can influence (e.g. product quality, customer satisfaction, product innovation). It is this specific combination of resources and critical success factors that leads to the generation of value. However, companies do not create value in the same fashion. Different companies create value in different ways.

This process, in fact, is strongly firm-specific as it is intrinsical y linked to the features of the company in which it takes place. It strictly depends on the contingent factors that affect the business context: the vision, the mission, the strategic priorities, the relationships between managers and employees as well as all those factors that make the way in which the company operates unique and unrepeatable. For example, the managers’ knowledge about the competitive dynamics of a particular sector can contribute to the creation of value only if the company plans to compete in that sector.

Since the 1980’s, increased competition and the advent of information and communication technologies have turned the value creation process of companies into something that has become more and more dynamic and complex. In fact, value creation does not depend only on individual value drivers, but rather, on the relationships among them. Therefore, the value drivers are not rigidly separated and each of them does not develop in its own way, independently of the others, following its own logic. It is impossible to identify a priori the features and functions of the resources in a company because they depend on the original combination that is set up in the specific company context. Moreover, the relationships among the value drivers are not stable; they do not always display the same features and they may even cease to exist or change intensity, direction and nature.

Managers’ actions that are expected to affect a specific business asset may, however, also be relevant to other resources. This is the reason why the relationships among value drivers are often fragile, ambiguous and potential. Relationships among the resources of a company can be non-linear: this is the case when key employees decide to switch to the competitors, for example. This change can destabilize the entire business system with negative impacts on the value creation process. For these reasons, it is becoming more and more important for companies to be able to manage the value creation process. This is possible through the visualization of the value drivers involved in the value creation process and, above al , through the representation of the relationship network that links resources and critical success factors and leads to value creation. The awareness of the causal relationships, of their strength and of their nature allows the company to effectively and efficiently manage the value drivers. In this way, in fact, companies can take appropriate decisions in order to influence the situation in the desired direction and to increase the creation of value.

6.2 Why might the value creation process be difficult to discover?

Managing the value creation process can be a very difficult task. The knowledge of the value drivers involved, of the way in which they combine with each other, of the nature and the intensity of the relationships are rarely formalized and shared in the company. This knowledge, in fact, belongs to the managers who work within the company. They manage, on a daily basis, the value drivers and the causal links in order to increase the value created for the company. Their awareness of the contribution that each value driver provides to the value creation process drives their actions and their decisions.

For example, a manager may find a strong and positive relationship between the value driver “employee competences” and the value driver “product quality”. This belief is going to lead the manager to make decisions in order to:

1. Raise the skil s level of employees through training, for example

2. Encourage employees to provide as many suggestions as possible

If the manager’s perception is correct, these two types of actions should have a positive effect on the product quality and, consequently, on the creation of value.

However, the knowledge of the value drivers and their relationships is tacit and therefore, difficult to access and to visualize. Managers themselves find this kind of knowledge hard to elicit and to manage. Even when an analysis is made through written reports, these do not always contain a clear description of the assumptions made on the dynamic relationships among the value drivers that underpin the creation of value. This is because the need to rapidly solve the day-to-day problems leaves little room for conceptualization and reflective activities.

In this perspective, managers are considered to be information workers because they spend a lot of their time absorbing and processing information on problems and opportunities. One of the fundamental challenges that managers face is that their environments are extremely complex, from an information point of view. In order to understand managers’ actions, it is necessary to build and analyze the content (value drivers) and structure (relationships among value drivers) of the mental models through which they filter information, structure knowledge and make decisions. Therefore, it is necessary to use a tool which can facilitate this operation, by making explicit managers’ knowledge of the way in which the company generates value.

6.3 What is a value creation map?

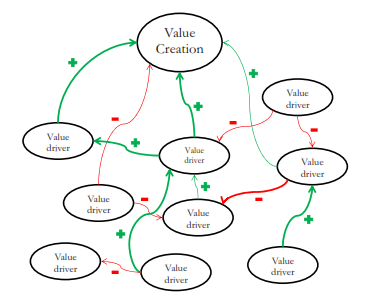

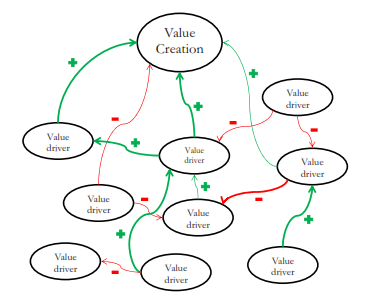

A value creation map is a tool that makes it possible to visualize and to explain the managers’ mental models, reproducing the specific ways in which a company creates value. A value creation map is made up of two elements: nodes and arrows. The nodes of the map are the value drivers which the management considers important to value creation. The arrows, instead, identify the relationships among the value drivers. The thickness of the arrow indicates the strength of the relationship. The relationships among the value drivers can be of different natures:

1. Positive, when one value driver positively affects another one. In this case, the arrow is matched with a plus sign

2. Negative, when one value driver negatively affects another one. In this case, the arrow is matched with a minus sign

3. Doubtful, when the influence of one value driver on another one is uncertain.

The value creation map enables us to understand the ways in which managers perceive the succession of events, give meaning to the relationships between the events themselves and evaluate alternative courses of action.

As with the use of geographical maps, with value creation maps, too, we can assume that a certain ”path”, made up of decisions and actions, is going to lead to a particular ”destination”, that is, the creation of value.This tool makes it possible to identify the most important value drivers and to visualize the relationship network among them, representing the peculiar way in which value is generated in a given company context.

6.4 The building process: A two-step method

The building process of a value creation map aims to elicit the mental models that are triggered in managers, in certain situations. As mentioned before, these models have a largely tacit nature because they are deeply embedded in individuals and they are rarely made explicit. This conversion is a very hard task because the value drivers and the relationships among them are difficult to explain and communicate so that managers themselves consider the interpretation of the decision rules that drive their actions very critical.

The building process of a value creation map consists of two steps: firstly, the elicitation of the value drivers considered important by the managers and secondly, the identification of relationships among the value drivers. Before analyzing each step, it is relevant to clarify what kind of managers and how many managers should be involved in the building process of the value creation map.

6.4.1 What kind of managers? How many managers?

A critical aspect, already in the design stage of the map, relates to the identification of what kind of managers and how many managers should be involved in the development of the value creation map. Obviously, these choices are linked to the size and the features of the company to be analyzed, so the following should be considered general considerations.

Unanimous opinions in the field argue that the identification of the value drivers and the relationships among them is up to the top managers, because they are the ones who are going to use the map and they have the skil s needed to support its building. However, a purely strategic vision does not seem enough when the aim is to identify the links between individual actions and effects. The operative knowledge possessed by middle management helps to better identify the nature and intensity of the relationships and to consider the potential impact of the value drivers that top managers may not be able to assess. Therefore, before proceeding to the map building, it is particularly important to identify the management levels to be involved, according to their skil s and their expertise.

Concerning the number of managers to involve, previous studies on value mapping show that involving three to five individuals is sufficient to obtain adequate knowledge of the value creation process and avoids making the map building process too complex.

6.4.2 First step: Identifying the value drivers

The aim of the first step is to identify the value drivers considered relevant by the managers for the purpose of creating value. The tools that appear to be the most suitable for this purpose are the semi– structured and the unstructured interview. The questionnaire and the structured interview, instead, are not very flexible or adaptable to specific situations and this makes them inappropriate for explaining the contents of the mental model created by a manager in a given situation. Both the semi-structured interview as well as the unstructured one, in contrast, has an high degree of flexibility. They allow deep access to the conceptual categories used by the manager, by identifying his/her interpretations of reality and the motivations that drive his/her decisions.

These interviews should be conducted at the individual level as tacit knowledge is personal and not always shared within a team of managers, even though they may work closely together for a long time. Interviewing managers allows them to reflect on the actions that they usual y put in place. In this way, the researcher can discover aspects of behavior which were tacit until that moment. The first question to ask should be a general one, such as: “What are the factors that lead to the success of the company?”. The aim is to gradual y uncover deeper and deeper layers of the managers’ knowledge. In order to identify the causes that affect the value drivers, it is important to ask managers to tell anecdotes and give examples, some positive and others negative, regarding factors that have generated success or failure in the company. Asking them for anecdotes and examples is particularly powerful because it forces managers to explain what real y happens, it stimulates them to provide details and triggers, in turn, other thoughts and stories. Through story and language, in fact, managers give meaning to events that occur and to their actions and they can organize their experience. In this way, it is possible to discover how the value drivers come “into action” in the company under analysis. After finishing the interviews, the researcher analyzes the transcripts in order to prepare a list containing the value drivers considered critical by the managers interviewed.

6.4.3 Second step: Identifying the relationships among value drivers

The second step aims to identify the causal relationships among the value drivers in the list. In particular, there are two methods that can be employed for this purpose. In the first method, the researcher interprets and identifies the relationships among the value drivers in the list. In particular, he/she is responsible for identifying the strength and the direction of causal links through his/her understanding of the company context (resulting from past and present experience) and the interpretation of the managers’ perceptions. The second method, however, requires the managers previously interviewed to identify the relationships among the value drivers in the list. This can be done through the creation of a focus group. This second option is preferable for several reasons.

Through interaction and discussion, the members of the focus group can reflect on their behaviors and on those of others, bringing into question the meaning of the value drivers and the relationships that are activated in specific situations. At this stage, managers are also called upon to express their opinion on the intensity and the sign of the relationships, while the researcher has to provide them with the greatest possible support, but should avoid leading them to pre-determined results.

The meaning of the value drivers comes from language. In particular, the meanings are developed and refined during the interaction and discussion in the focus groups: the meaning of the value drivers becomes clear to a manager from the reactions that their use provokes in other managers. Therefore, the value drivers and the relationships among them which are contained in a value creation map are formed through interaction and discussion.

Managers are encouraged by the researcher to modify and enrich the map, by adding, removing or moving value drivers and relationships. This process allows them, on the one hand, to analyze the evolution process of the map and, on the other hand, to understand the perspectives of others.

The above mentioned process leads to a map which is “owned” by the focus group members. It allows them to achieve a deeper sharing of the meanings given to the previously identified value drivers in the list. Furthermore, during this step, the creativity of managers is greatly stimulated, so new value drivers, not in the building process of value creation maps concerns the study of social processes that enable the originally identified in the list, may emerge from the group discussion.One of the main challenges in the building process of value creation maps concers the study of social processethat enable the group to acquire and shape information and to make shared decision. Regardless of the method chosen to identify the relationship among the value drivers, the aim of the building process is to create a map similar to that represented below:

Figure 20: The value creation map

6.5. Refining the value creation map

As it should be clear from the previous paragraph, the value creation map created at the end of the building process cannot be considered definitive. The intrinsic instability of the value drivers, but above all of the relationships identified, determines the need for updating and refining the map previously developed. This need can be felt as a result of a change in the conditions inside or outside the company. This can affect the relationships identified before or can create new links. The awareness of these changes, in fact, alters the managers’ perceptions and assumptions which led to the building of the “initial” value creation map.

Furthermore, the need to update the map can emerge from the actual deployment of business processes. This can reveal the real effects of managerial actions on the value drivers and the value creation process. So, it is only natural that there can be differences between the “initial” map, developed on the basis of the assumptions expressed by managers, and “in progress” maps, progressively updated in order to take into due consideration the changing internal and external conditions.

Even when an “initial” map is substantial y different from the “updated” maps, the tool does not lose its effectiveness. The value creation map, in fact, is dynamic in nature. The differences should serve as a boost for managers to reflect on what relationships have actual y occurred, to understand the reasons why the “initial” relationships have not taken place and, therefore, to understand how to set them up again. Thus, the instability of the content of the value creation map is a “technical” feature that enhances the role of this tool in supporting management’s learning process.

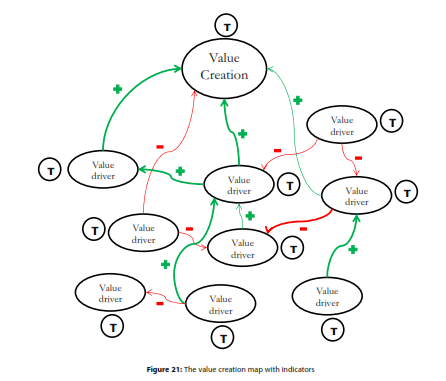

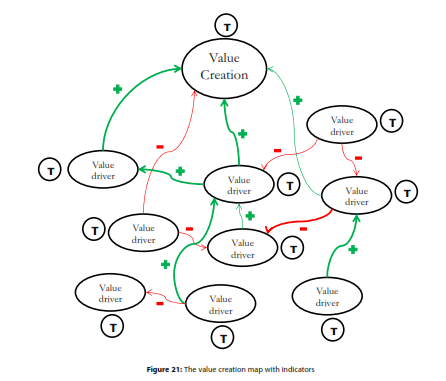

6.6 Value creation maps and indicators

The building of the value creation map can be considered the basis for setting up a measurement system. In particular, the map can be considered the skeleton on which to build an appropriate set of indicators

(I). These indicators should be coupled to the nodes of the map.

The use of a value creation map as the foundation upon which to build a specific set of indicators can improve the selectiveness of the measurement system. The focus on critical aspects of the value creation process avoids the risk of squandering management's attention by providing an excessive number of indicators. Moreover, a measurement system built on the basis of a value creation map allows an appropriate balance between lagging indicators, mainly financial, and leading indicators, typically quantitative-physical and qualitative. This is because the development of a value creation map makes it possible to identify the drivers of the value creation and to trace the causes that affect it.

The conciseness, accuracy and reliability of lagging indicators is useful for nodes downstream of the value creation map, that is, those associated with the value drivers directly linked to the value creation. These indicators are not so difficult to design and to build, but they are oriented to the past, so they do not have the ability to reflect the current activities. The inclusion of leading indicators, built on a specific node and a specific relationship, are able to provide prompt signals and to monitor and govern the deep causes of value creation. In this way, these indicators can anticipate the final results and drive the performance of lagging measures.

Furthermore, the correspondence between the value creation map and indicators provides the management with relevant information on the timing of actions on the value drivers. In particular, monitoring the trend of indicators over time can help to ”capture” the length of the lag, i.e. the time it takes for an indicator of a value driver to begin to influence the indicators of related value drivers, first, and influence the financial performance, later. For example, a measure that ”captures” the effectiveness of research and development activities (e.g. number of patents) is not likely to affect the financial performance in the short-term.

It probably needs a temporal lag of several years. In contrast, leading indicators related to product quality (e.g.: defect rates and on-time deliveries) can influence the economic and financial indicators with a shorter lag. Managers should pay attention to this aspect because the lack of an immediate effect on financial performance may simply mean that actions take time before generating an economic benefit. Therefore, management actions that may be deleted or changed because they generate no immediate effects, might instead be ”reconsidered” when managers become aware of their potential effects in the medium and long term.

The ”matching” between value creation and map indicators, moreover, can provide useful information on the persistence of the effect of a particular action on value drivers, i.e. how long the effect persists once it is started. In fact, the effect may be only temporary and affect the indicator trend of the value driver to which the action is directed only for a short period of time. Or, the effect may persist and influence the indicator trend for longer periods of time.

Final y, indicators can play a leading role in the refining and updating process of the map. The relationships among the value drivers are, by their nature, unstable. In this sense, the dynamics of the indicator is of primary importance in order to test the existence of the relationship and to verify its trend over time, since the intensity of the links may not be unvaried. In other words, indicators may signal effects on the value drivers that are not manifesting themselves with the timing or the intensity which had been considered in the “initial” map. This can provide useful information on possible changes to be made in order to refine and update the map over time. This gives the system a high degree of flexibility and adaptability which is consistent with the dynamics of the value creation process.

6.7. Pros and cons

The building and the use of a value creation map can be very useful for managers. The advantages are mainly related to the effects that this tool can have on their management and learning skil s. The visualization of the value drivers and the relationships among them allows managers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the value creation process. This provides them with the opportunity to

maximize the former and lessen the latter, through a more aware management of the individual value drivers and the relationships among them. In this way managers can make the value creation process in the company less fragile and vulnerable because they can avoid the risk that some value drivers remain unmanaged.

Managers’ awareness of the creation of value increases not only during the map building process, but especial y during the refining and updating process. It must be highlighted that the most important benefit of this stage, in fact, consists in management learning: the refinement of the managers’ perceptions and assumptions improves their ability to interpret and manage the dynamics of value drivers and the direct and indirect effects of same on value creation.

The matching between map and indicators further enhances this aspect. Such a measurement system makes it possible to understand the impact of a managerial action on a specific value driver through the analysis of the change of the indicator. From this essential y static perspective, the map allows the switch to a dynamic view by examining, first, the direct impact also on indicators of other related value drivers and, where possible, the indirect impact on value creation. For example, the map could highlight a positive relationship between the value driver “col aboration with employees”, matched to the indicator “number of suggestions for each employee”, and the value driver “product quality “, associated to the measure” defect rate “.

This matching permits the measurement not only of the individual value drivers, but also of the relationships among them, providing the opportunity to manage that link and to increase the positive impact of a value driver on the related ones. Such a measurement system is strongly oriented to action as it can provide relevant and timely information to support the managers’ decision making. The identification of indicators from the mental model of managers who manage the value creation process daily increases the overall quality as well as the signaling ability of the measures system. This can progressively lead to an increased likelihood that decisions cause a series of multiple effects consistent with the expected results.

Therefore, the map represents an important tool to improve decision making when managers are faced with complex and ambiguous situations. The simplified representation of reality perceived by managers can help to identify and to consider alternative courses of action, as well as to choose the option considered appropriate in order to increase the value creation.

However, it must also be noted that there is a drawback linked to the use of value creation maps. It consists in the potential attitudes of resistance or rejection of the tool. The development of value creation map requires, in fact, the willingness to explain and bring into question the interpretative models of managers. This demands a significant time investment in reflection and conceptualization activities. Not all managers may be available or willing to devote time to eliciting their knowledge about the value creation process in the specific company. Therefore, the possibility that the use of value creation maps can generate the effects previously described is also affected by these considerations.

Sum-up questions for chapter 6

• Why might the value creation process be difficult to discover?

• What is a value creation map?

• How can a value creation map be built and refined?

• Why can matching a value creation map to indicators be useful for managers?

• What are the pros and the cons of building and using a value creation map?