7 Business model innovation

(Written by Yariv Taran, Assistant professor, PhD)

[Please quote this chapter as: Taran, Y. (2012), Business model innovation, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon. com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

Due to today’s ‘hypercompetition’ (D’Aveni 1994) in a globalizing world, companies in all industries worldwide find themselves competing in ever changing environments. Those changes force companies to rethink their operational business models more frequently and more fundamental y, as innovation based solely on new products and aimed towards local markets is no longer sufficient to sustain their competitiveness and survival. Competitors can relatively easily copy products, and local market segments today are often quickly captured by global rivals located elsewhere.

The IBM global CEO study 2006 held among 765 top CEOs is also in favor of that claim – business model innovation matters. Competitive pressures have pushed business model (BM) innovation much higher than expected on industrial priority lists. According to that study, approx. 30 percent of CEOs are pursuing business model innovation initiatives and quite rightly so.

However in most cases, managers’ strategic preference typical y involves “more of the same” (mostly product) innovations that keep their company fixed on the same line of value propositions, using the same, or somewhat similar, technologies, aimed at the same target customer (e.g. Christensen, 1997). Consequently, the business model in many of those cases is accepted to be fixed on a certain way of doing business, and for that reason it has hardly ever been questioned or changed significantly.

Unfortunately, business models and their innovation are a huge challenge, both theoretical y and practical y. Much is known about innovation – especial y radical product innovation, much less specific business model innovation theory has been developed. And although many managers are very eager to consider more disruptive changes to their business model, they do not usual y quite know how to articulate their existing or desired business model, or, even less so, understand the possibilities, or rather the processes, available for innovating it.

The objective of this chapter is therefore to propose several processes that are available for companies for innovating their business models.

7.1 Method

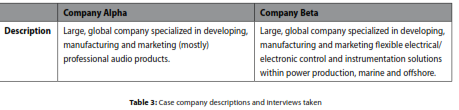

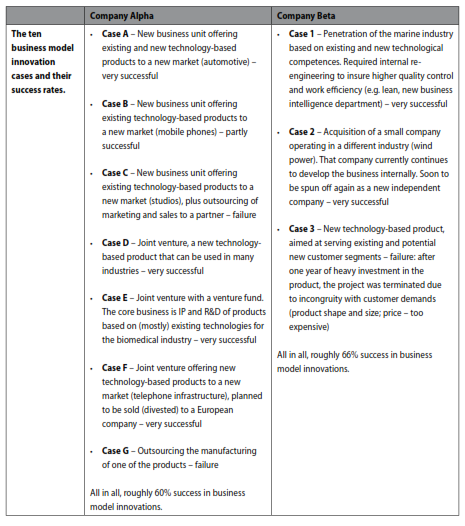

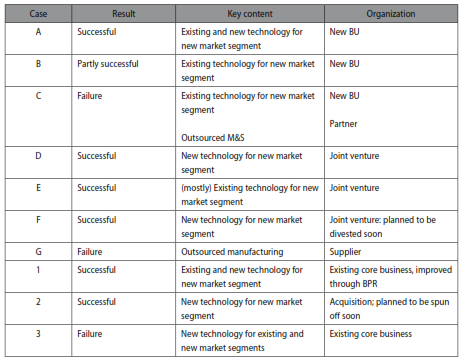

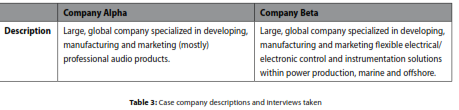

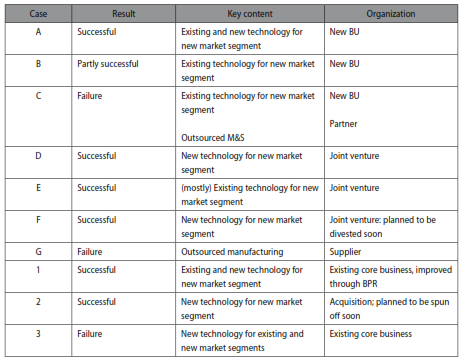

Ten retrospective case studies of BM innovation processes undertaken by two industrial companies (see Table 3) provide the empirical basis for this paper. We selected these companies based on their (relatively) successful, yet somewhat different, BM innovation experiences over the years. The study started early 2009 and is still in progress.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the overall research, multiple qualitative methods were used to collect the data. The data collection was done through desk and field research. The desk research involved collecting of information through books, articles, websites, as well as documents received from the two companies. The field research consisted of face-to-face interviews with managers who had actively participated in, or had been in charge of, the new business development initiative, along with e-mail correspondence, company visits, and questionnaires.

Given the mostly explorative nature of the research we used a semi-structured (standard) questionnaire, which allowed the individual respondents maximum freedom to explain their views on the new business model and their understanding of the innovation process, and enabled us to collect the data we felt we needed for the purpose of our research at the same time. Since the case studies were analyzed retrospectively, the data could not be acquired through observations. Table 4 summarizes the case study data collected.

7.2 Analysis

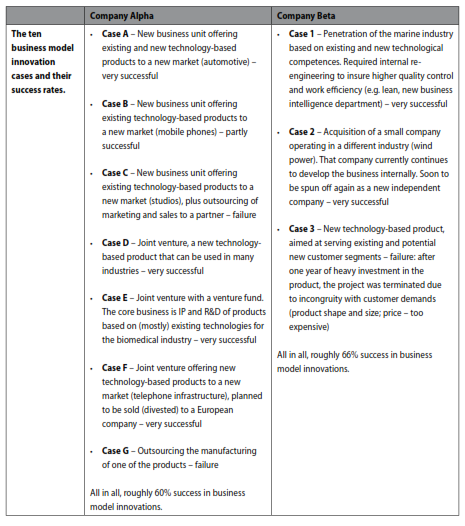

7.2.1 Characteristics of the business model innovation and success rate

Company Alpha: Throughout the years, company Alpha engaged in seven business model innovations. Four cases (A, D, E and F) were very successful. In three cases, the company either partly succeeded (case B), or failed to succeed (cases C and G). All successful cases involved the exploitation of existing technology (case B, C, and E), or the development and exploitation of new technology-based products, together with a partner (cases A, D and F), in a market segment new to company Alpha. Case A resulted in a new internal manufacturing unit; the other success cases in a joint venture. The two failure cases were attempts to outsource the production (case G) or marketing and sales function (case C) to a third party.

Two factors caused their failure. First, the partner did not match the company’s high quality standards. Second, they realized in a later phase (particularly case C) that the market was too small to play a significant part in the company’s turnover. In case B, company Alpha and a partner company combined some of their competences and developed two mobile phone types. One product was a partial success while the other type did not succeed. Nonetheless, this project would have been continued if it were not for the financial crisis, which forced the company to become more focused in response to the 34 percent turnover loss.

Company Beta: This company engaged in three business model innovations, two of which became a success (case 1 and 2), while one attempt failed (case 3). Case 1 involved the application of existing, and the development of new, competences and technologies in a new market segment. Case 2, an acquisition, was much more risky for the company, both in terms of investment as well as time constraints, and involved the development and exploitation of new technology in a new market segment. In case 3, a failure, the company “pushed” a radical y new product into the market in an attempt to exploit a new emerging technology, without any idea of how customers would respond. Cases 1 and 3 were implemented using the company’s existing organization. As said, case 2 was an acquisition.

Table 5: Key characteristics of the ten business model innovations

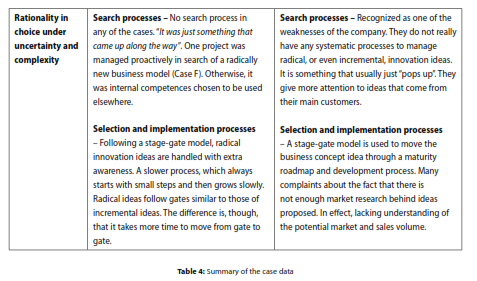

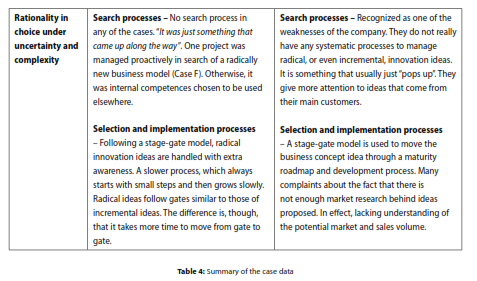

7.2.2 Rationality in choice under uncertainty and complexity

Company Alpha: In most cases (except case F), there was never a search process for new business models. Rather, ideas were slowly developed along the way based on their existing core competences (e.g. technologies, know-how). The company simply considered it obvious that existing competences would give them relatively easy access to other industrial settings. These competences include the ability to:

1. Outsource existing products and processes to a new partner (case G).

2. Transfer existing technologies and processes to another industrial setting (cases B, C and E).

3. Develop, in-house or together with a partner, and then transfer, new technologies and processes (cases A, D and F).

The challenge, in cases D, E, F and G, was to find the right partner to work with. The search for a partner, rather than the search for an idea, seemed to be the main challenge in these cases. Furthermore, in all cases except E and F, the company preferred to generate the idea and test it first internal y, starting with a low scale production process, and to consider growth in due course (e.g. through a joint venture, or a new business unit). This replication of previous business model innovation processes seems to be a winning formula for the company, and is expected to be followed relatively similarly in future business model innovations.

All new ideas have to pass through three strategical y oriented gates before they are allowed to continue further to implementation. At the first gate, the idea is presented to the concept manager. The second gate involves a presentation of the so-called initial proposition to the top management. At the third gate, the top management decides whether or not to commit to the concept that has been worked out, and to the detailed business plan that was developed. With every approval, the budget available for developing the innovation increases until, after the third gate, all the funding needed to develop, produce and commercialize the innovation is available to the innovation team. Further downstream, the gates are managed by a cross functional team (idea factory, R&D, production, marketing and sales), which provides the innovation team with the flexibility to manage the stage-gate process from gate to gate as they see fit. At each gate, the team receives a checklist that must be completed before the next gate meeting.

Company Beta: As was the case with company Alpha, there was never a formal search process for new business models. Radical y new ideas emerged over the course of time, either through existing technological capabilities (case 1, case 2), as a reaction to emerging competitors’ technologies (case 3), and/or simply to reduce cost (case 1). Furthermore, the failure of case 3 made the management team even more aware of the need to better understand customer demands as a basis for selecting innovation ideas.

Company Beta, too, follows a stage gate model for moving new product and business concepts through a process roadmap and development process. For each innovation project there is a steering group, which is situated at the gates. This group includes representatives from the management team and the R&D group, and a product/project manager as well as supply chain staff (purchasing, distribution). The business intelligence unit, however, is not involved in that process. For that reason, according to one of the company managers, the discussions in the steering groups at the gates are concerned with performance errors in existing products, rather than searching for whol y new products/businesses that could better meet present, and potential y new, customer demands.

7.2.3 Cross analysis

Both companies try to reuse successful business model innovation processes (new idea generation and implementation processes). However, while company Alpha is keen on pushing ideas and technology into the market place, company Beta is more in favor of adopting a customer pull strategy. Furthermore, both companies try not to repeat failures made in the past. Consequently, the failed outsourcing attempts of company Alpha (cases C and G) has led the company to re-experiment with familiar, “pushed”, business model innovation processes, while company Beta, based on the failure of case 3, has chosen to no longer push new ideas and technologies into the market place, without consulting their customers first.

These observations has led us to conclude that instead of learning to improve, both companies tend to “simply” repeat successful business model innovation processes and, equal y, “simply” to drop unsuccessful approaches. This lack of experimentation with new business model processes, and the lack of learning from their failures may decrease the growth potential of both companies. Yet, this observation is also confirming our statement mentioned earlier, namely, that in most cases, managers’ strategic preference typical y involves “more of the same” innovations (or, in this case, “more of the same” innovation processes).

7.3 Discussion: Single vs. multi BM innovation

As the cases suggest, there are many possibilities for innovating the company business model. A company can, for example, strategical y choose to innovate the core business fundamental y by transforming the entire business from “as-is” into a completely new one. Cases 1, for example, is an il ustration of such innovation scenario.

Business model innovation can also come in the form of mergers or acquisitions (e.g. case 2). In such cases, business model innovation is considered to be a highly risky process, since the company partly, and sometimes even completely, abandons its original business and core processes, and develops a completely new business that encompasses new processes the company was not familiar with in its past.

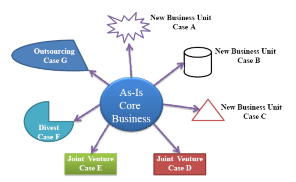

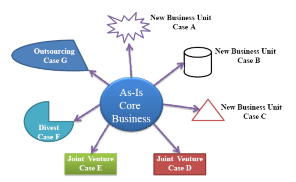

An alternative process to innovate a business model would be to keep the core business ful y operational (“as-is” followed by continuous improvements), and alongside it, to develop additional business models aimed at serving new markets and operating in other industries than those the company was familiar with. Company Alpha, for example, was particularly successful in launching such business model innovation initiatives, as il ustrated in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Company Alpha’s business model innovation initiatives

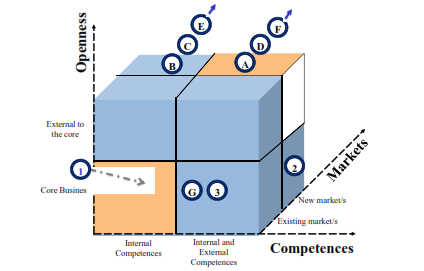

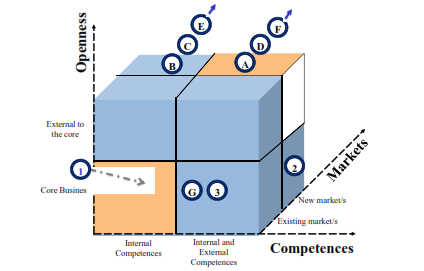

On the whole, by embedding Chesbrough’s (2007) open business model innovation thinking into our cases findings, we can argue that, on an aggregate scale, business model innovation possibilities can be perceived under three categories, namely:

1. Level of business model openness – i.e. innovating the “as-is” core business or (also) outside it.

2. Internal and/or external competences used through the innovation process.

3. Existing and/or new markets that the company is operating in.

Figure 23 il ustrates what we argue to be the business model innovation “cube”, where we have placed the business model innovation cases of companies Alpha and Beta in the accurate boxes for il ustration (e.g. Case 1 – BM innovation that took place in the existing core business, using solely internal competence, aimed to serve a new market).

Figure 23: The business model innovation cube

As the model suggests, the BM innovation initiative on the bottom left box (i.e. core business, internal competences, existing market/s) will manifest itself as somewhat incremental BM innovation initiative. Alternatively, the upper right box (i.e. external to the core, internal and external competences, new market/s), will manifest itself as a multi business model initiative, and gives a more open view (Chesbrough, 2007) to the business model of the company. In these cases, a company choses to create a new business while still keeping the “as-is” core business ful y operational – if the business model innovation initiative fails, the company could continue operating in existing markets, provided that the financial losses (due to the failure) were not too large.

Yet, it should be noted that given that al business model innovations are loaded with risks, it is stil highly questionable which of the initiatives should be the preferred one to pursue. Open, network-based innovation also brings with it many (other) risks, and with that, new chal enges. Obstacles associated with network– based innovation can manifest themselves as e.g. difficulties in finding a common value for the network partners to work with; in understanding the synergy (i.e. “who’s doing what?”); in insuring trust between partners; in developing a joint profit formula; in securing sustainability to the new business; in securing intel ectual property rights (e.g. Chesbrough 2007, Tidd and Bessant 2009, Miles et al. 2005, Dodgson et al. 2006, Ahmed and Shepherd 2010).

7.4 Conclusion

Companies today, in some industries more than others, invest more capital and resources just to stay competitive, develop more diverse solutions, and increasingly start to think more radical y, when considering whether or not to innovate their business models. However, although many managers are very eager to consider more disruptive changes to their business model, they do not usual y quite know how to articulate their existing or desired business model, or, even less so, understand the possibilities, or rather the processes, available for innovating it. The objective of this paper was therefore to propose several processes that are available for companies for innovating their business models.

The cases presented and analyzed here suggest that managers can perceive business model innovation possibilities under three levels of analysis, namely: degree of business model openness; (supply of) competences used through the innovation process; and number of markets that the company is operating in (Figure 23).

Final y, several approaches are possible to extend and test the results presented in this paper, including more case studies, to shed additional qualitative light on the findings presented here, or a survey, especial y for generalization purposes.

Sum-up questions for chapter 7

• What is your understanding to the term “Business Model”?

• What does it mean to innovate the business model?

• What is the difference between product innovation and business model innovation?