8 Globalizing high-tech business models

(Written by Romeo V. Turcan, Associate professor, PhD)

[Please quote this chapter as: Turcan, R.V. (2012), Globalizing high-tech Business Models, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon.com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

8.1 Setting the scene

In the early process of the emergence of new international ventures, entrepreneurs are constantly in a ‘tension extinguishing’ mode as they are trying to ease tensions in the organizational gestalt which consists of mutual y supportive organizational system elements combined with appropriate resources and behavioral patterns (Slevin and Covin, 1997). Two sources could be identified that effect these tensions, namely strategic experimentation (Nichol s-Nixon, Cooper, and Woo, 2000) and business model experimentation.

The strategic experimentation differs from the concept of strategic change in that it is not predicted on the assumption that these actions involve realignment of an existing strategy; rather, the emphasis is on forming and executing a strategy in an effort to reach a steady state for the first time. Entrepreneurs experiment with the business models of their international new ventures in an attempt to establish the dominant logic of the venture, whereby entrepreneurs reach an agreement on the way in which the business is conceptualized and critical resource allocations decisions are made (Prahalad and Bettis, 1986).

For example, tensions occur in decision making when entrepreneurs are required to determine the growth path of the venture. What shall the growth scope be: local, international, or both? What shall the international growth pace be: gradual or rapid? What shall the product mix be: only product-base, service-base, or hybrid product mix? How shall the venture enter the market: through dealings, structures, or both? What market entry modes to pursue? Will the venture grow organical y or by attracting venture capital? Opting to attract venture capital, entrepreneurs are to deal with dyadic tensions that are the result of differences in entrepreneurs’ and VCs’ goals and measures of success (Turcan, 2008). Shall entrepreneurs look for strategic partnerships that may generate additional tensions as the new venture may become captive to the chosen strategic partner (Turcan, 2012)?

This chapter will focus on gestalt tensions during the early process of emergence of international new ventures. International new ventures are defined as ventures that aim to derive profits from international activities right from their inception or immediately after (Oviatt and McDougal , 2005). These ventures usual y attract venture capital due to their potential for very high gains in combination with the availability of early exit strategies (www.nvca.org). At the policy level, international new ventures are seen as critical engines of economic growth (OECD, 2004). The data that are presented as part of the discussion throughout this chapter are derived from Turcan (2006); a summary of the data is provided in the Appendix.

8.2 Tensions at the inception

Since by definition international new ventures internationalize instantly at or immediately after their inception, the issue of whether to internationalize or not is irrelevant. The central issue then is how to internationalize. A set of tensions arise when entrepreneurs have to decide what business model to adopt. For example, should the venture be based on a product-led business model; service-led business model, or a hybrid business model in which both service and product business models co-exist? The experience suggests that in order to internationalize, entrepreneurs shall adopt product-led (or hybrid) rather than service-led business models. The underlying assumptions behind such decisions are the uncertainty and limited scope for growth, which entrepreneurs have to and eventual y will have to live with in service-led ventures. Here is how entrepreneurs reflect for example on the uncertainty:

‘We were a service based organization, like it or not. We were doing a lot of outsource development, which meant that you do not real y build a sustainable value into your business. So when you start January first next year, you start from scratch; you do not have a number of contracts that are related to maintenance or whatever …it was very much a wish for us to look at annuity based revenue opportunities’ – the marketing director of Finance-Software;

‘I spent the late 80s going through a recession with my own business being in real, real troubles. And all you have to do is to go out and talk to people, and survive. That is the fundamental when you are a small, service business with no capital behind: everything is organic. You eat from what you earn. And that is it’ – CEO of Tool-Software.

As to the scope, it is actual y difficult to expand and internationalize a service-led business. Simply put by one of the co-founders of Finance-Software after an unsuccessful attempt to penetrate the German market: ‘ Services do not travel’. The same view emerged from the discussion with an investor:

‘ Service-based businesses have difficulties to internationalize…just turn it another way: why would you go abroad in the first instance. I’ve seen IT-integrators who expanded to London: fair enough – London is a good, lucrative market. And, they started saying that they want to open an office in California. And you just think: why? Just because it is exciting and sexy to work in California! You have minor technology and your people are not that much down than them… They will do that for a year or two and after they realize how difficult it is, they will retrench’ – the venture capitalist.

It is critical thus for the entrepreneurs to understand not only that service-led and product-led businesses require different business models, but also the fact that the transition from a service-led business model to a product-led business model produces tensions in the organizational gestalt: e.g., differences in the cost structures, levels of margins, marketing and sales, market positioning, and administration are the chief sources of these tensions as several entrepreneurs explain:

‘ At this point we felt that there was a need to establish more of a real company: to hire full-time development staff; to establish an office. …Sel ing services however is completely different pitch from sel ing the product. Services tended to be low volume, very high value contracts, over one year, or six months; but the product would be sold at a much lower price, therefore we had to be sel ing at a higher volume’ – CEO of Project-Software;

‘ We always recognized that software is an area where if you can get the right software product then you can get serious amounts of money out of it. Because unlike manufacturing a product, there is no manufacturing costs; there is initial development cost, but once you have developed the product then the profit margin you get out of sel ing that price of software is very high’ – CEO of Finance-Software.

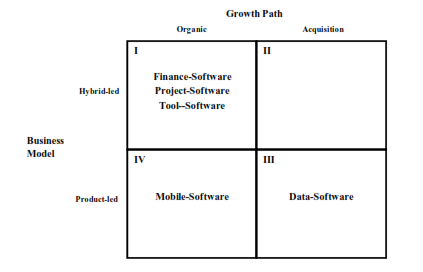

These tensions that are built within the organizational gestalt have to be alleviated quickly by assembling and deploying appropriate resources in order to support the initial international development of the new venture. Entrepreneurs have at their disposal two generic growth paths to make this happen: either through organic growth or acquisition growth2. These paths are business model dependent. For example, entrepreneurs who aim to adopt the hybrid business model in order to develop the product might pursue this goal via organic growth. Entrepreneurs who aim to adopt product-led business model right after the inception of the new economic activity have a higher chance of attracting venture capital. Since both entrepreneurs and venture capitalists agree that services are difficult to internationalize, it follows that the growth path of a company is contingent on product-led business model and/or hybrid business model. Although, entrepreneurs’ views on what business model to adopt may differ as presented below:

‘ As we were diversifying we felt that there were opportunities for cross sel ing between our consulting clients, i.e. to sell our product to those clients. At the same time we felt the need to keep those businesses separately, because they are quite different in nature’ – CEO of Project-Software;

‘ Our move was very much to become a product focused business. The plan was to continue to make revenue from service, take some of our guys out of that kind of revenue earning, which was an investment in our part, and keep them, as an investment, working on the product’ – CEO of Finance-Software;

‘ We started of as a service business. We had a working project in hand that we finished. That gave us some revenue to start with. Real y the goal was to switch to product revenue. As soon as we developed the first version of the product, we focused on sel ing the product rather than the service’ – CEO of Data-Software;

‘ We structured our business to product development. We also built a service capability, which generated cash and was meant to be project oriented at developing sort of tactical revenue real y’ – CEO Tool-Software.

2 Here, organic growth refers to the situation when entrepreneurs i) invest their own money to establish a new venture or ii) re-invest their profits to start a new business idea. Acquisition growth refers to the situation when entrepreneurs use external resources to finance these new economic activities via equity or debt.

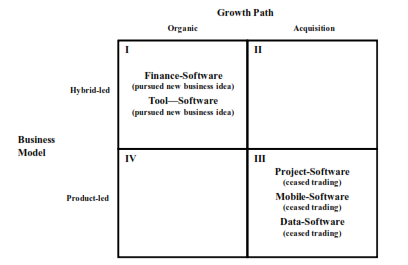

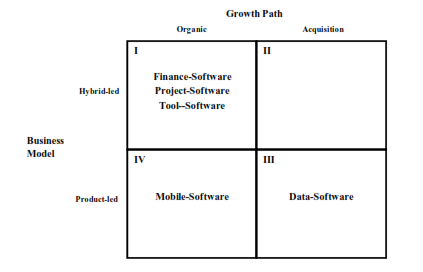

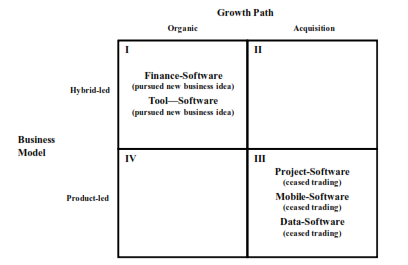

The evidence suggests that international new ventures which adopt hybrid business models have a higher chance of surviving. Figure 24 below shows the strategic intent at the inception of new economic activities and the actual strategy at the time of crisis. Finance-Software, Project-Software and Tool-Software pursued the identified international business opportunities by adopting a hybrid business model, i.e. they continued providing services, and at the same time invested their own profits into the product development. Cases D and E, having raised initial venture capital, pursued the identified opportunities by focusing on a product-led business model. At the point of crisis, Finance-Software and Tool-Software were still pursuing hybrid business model strategy and were growing organical y. Project-Software, having adopted a product-led business model, together with Data-Software and Mobile-Software could not cope with internal and external pressures and ceased trading. The following section will discuss the effects of these changes in the business models and the growth paths on the internationalization efforts of the new ventures.

a) Business models and growth paths at the inception of the new venture

b) Business models and growth paths at the moment of crisis

Figure 24. The evolution of strategic intent

8.3 Dyadic tensions

Entrepreneurs who aim to adopt the hybrid business model in order to develop the product might pursue this goal via organic growth. Entrepreneurs who aim to adopt product-led business model right after the inception of the new economic activity have a higher chance of attracting venture capital. These variables, however, might control each other in a loop. Entrepreneurs may change their original intentions of adopting a hybrid business model in order to pursue the product development under VCs’ pressure and adopt product-led business model instead. Consequently, this vicious relationship may well be the source for disagreements and tensions between the entrepreneurs’ and the VCs’ agendas.

That is, as a result of receiving venture capital, entrepreneurs have to alleviate another type of tension: dyadic tensions. Specifical y, these tensions materialize as the result of differences in the entrepreneurs’ and the VCs’ goals (Turcan, 2008). For example, entrepreneurs want to achieve profitability via long– term growth, whereas VCs’ goals are to exit quickly via out-and-out growth – an agenda driven by the life cycle of VCs investment portfolio and the success rate of this portfolio as one VC explained:

‘ We have a target to invest from 15 to 20 mil ion pounds a year. …The success rate on average is three out of ten are absolute stars: you give the business plan, and they completely deliver that. Then, we would see one or two out of ten would go bust; and the balance is somewhere in the middle’ – venture capitalist.

As venture capital comes in, it pushes the growth forward, and it starts to climb the value curve. The ideal time for VCs to exit is when the internal rate of return that measures the investment retirement is at its highest value; usual y within three or five years after the investment was made. It follows therefore that within a maximum of three to five years from an investment, VCs will look for an exit. According to one business strategy consultant, however, ‘ …the strongest company is the one which forms the best relationships with its investors’.

Four types of goal alignment are identified: life changing opportunity; no marriage; il usive alignment and enslavement (Turcan, 2008). The ideal situation for VCs and entrepreneurs is when their agendas are aligned creating thus a life changing opportunity especial y for entrepreneurs. As often expected, however, some entrepreneurs just do not want to sell their company. And if, as a result, no compromise is reached, then there will be no marriage between the two, as one VC explained:

‘ When companies are coming to us with a wrong model, we may question them, query them, they may change it. But if they have different view from ours, we probably will not invest’ –venture capitalist.

These two types of goal alignment pose interesting questions for future research. For example, the importance of creating a life changing opportunity culture could be assessed by the value of the exit. That is, what would be the relationship between the alignment of entrepreneurs’ objectives in terms of exit at the initial round of funding and the value of the exit? It might be conjectured that that higher value at exit would be achieved in those firms that had the entrepreneurs’ objectives aligned in terms of exit right at the initial round of funding. Another pointer for research is to ask how different a value of an exit would be when the entrepreneurs’ objectives converge gradual y with VCs’ objectives during their marriage?

When entrepreneurs and VCs do not arrive at a consensus and as a result there is no marriage between the two, researchers may delve into the effects of denials of funds. That is, what happens to the firms that were denied funding to pursue the identified new economic activities? Will they pursue other avenues for funding, give up and grow organical y or fail? Crucial in this process of pursing other avenues for funding is the stigma associated with failure to secure first round of funding. The issue of stigma of failure becomes even more acute in countries like Denmark and Finland, where the VCs’ community and the advisors’ community are very smal , and susceptible to col usion.

There are situations when entrepreneurs are ignorant as to the VCs’ true agenda, hence the il usive alignment of goals. For example, when asked about the possible effect of VCs desire of quick exit on the performance of the company, the CEO of Data-Software was surprised to hear that VCs might even have this agenda:

‘ Do VCs want to exit quickly? I do not think that is true. We did not have any VC that was pressurizing for a short-term exit. They wanted us to grab the opportunity and maximize the value of the investment. Maybe some naïve entrepreneurs who are new comers to the game may believe in this’ – the CEO of Data-Software.

In this situation of il usive alignment of goals, for VCs it is easier to mitigate the effect of getting an investment, which is when entrepreneurs lose control having actual y retained the majority of the shares, via il usive control, by making entrepreneurs believe they are in control of the situation as long as they unknowingly and reflexively advocate VCs’ agenda. As several experts noted:

‘ The day entrepreneurs get venture capital, they lose control, because VCs are using shareholders agreement/contract that goes outside share earnings to have rights to do things and to stop things firmly in the house. They have rights to positive and negative control, i.e. to do anything serious they have to do in spite of the board’ –business strategy consultant;

‘ There is a side effect of taking VC money. In my experience VCs do want control. They want to exert control over the things that are not working. Typical y VCs will invest in the business and the management team that is there. By and large they will leave it alone, if it works’ – liquidator.

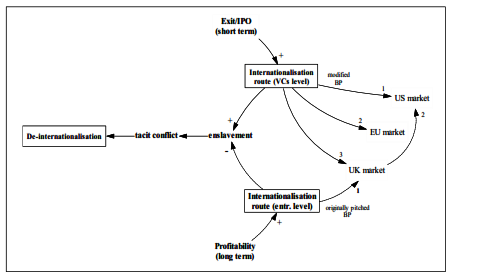

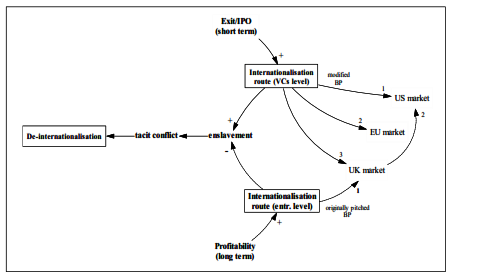

Entrepreneurs find themselves enslaved when they are trying to sell to the VCs their own business model and vision of growth, but VCs disagree and impose their own (Figure 24). For example, in order to get venture capital, the founders of Project-Software had to change their original business model and growth path from gradual internationalization (staring in UK, then moving to Europe, then to US) to rapid internationalization (going to US immediately, then to Europe, then maybe to UK). As the CEO of Project-Software explained:

‘ Our original pitch was to stay in the UK, get sufficient knowledge of the sales process, and then go to the US. At the very first meeting with our investors they said that this was a daft strategy; the vast majority of the IT sales is in the US, therefore you should be in the US straight away. Change your plan. So, we changed the plan, otherwise we would not get the investment’ – the CEO of Project-Software.

For entrepreneurs this is a catch-22 situation: they can not or do not want to say ‘no’ as they for example i) are desperate to get funding in order to develop and/or market their product, or ii) lack sufficient knowledge and experience to argue their case, or iii) are trying to avoid the situation when they could be blamed for the firm’s failure when things go wrong. By saying ‘yes’ to something they do not agree with, i.e. by enslavement, they force themselves into a tacit conflict situation, which entrepreneurs have to live with for the remainder of their marriage with VCs. It might be expected that if a consensus is not found to alleviate these dyadic tensions as quickly as possible, dissatisfaction with the deal will continue amplifying, and will inevitably lead to a divorce.

Figure 25. Enslavement as the effect of dyadic tensions

8.4 Conclusion

As shown in previous sections, international new ventures go through several critical events in their efforts to internationalize, and constantly are in tensions extinguishing mode. Entrepreneurs are trying to ease the tensions in the organizational gestalt as a result of a change in the business model and growth path. To internationalize, international new ventures have to develop a product-led business model as services do not travel. Opting to attract venture capital, entrepreneurs are to deal with dyadic tensions that are the result of differences in entrepreneurs’ and VCs’ goals and measures of success. Dilemmas occur in decision making when entrepreneurs are required to determine the pace, the entry mode, and the international marketing mix of the international strategy of the venture.

Once through strategic experimentation and business model experimentation a dominant logic is achieved, the questions that most need to be addressed by entrepreneurs are: to what extent is the chosen organizational gestalt continuing to deliver returns and positive performance, and if less than optimal, what change would better effect attainment of projected targets. Agility plays a crucial role in effecting the desired and/or needed change. Agility is about flexible decision making and a flexible cost base structure that allow decision makers (entrepreneurs and VCs) to scale up and more importantly to scale down according to the activity level that the firm is experiencing (Turcan, 2008, p.295).

The other vital point in effecting a change is for decision makers to actual y acknowledge that there is a need for change and act accordingly rather continue pursuing failing course of action. If decision makers eventual y do recognize that the existing organizational gestalt is less than optimal, and decide to stop committing further organizational resources, the question then becomes at what point too little is not too late (see e.g., Turcan and Marinova, 2012).

Sum-up questions for chapter 8

• Which types of critical events do new international ventures go through?

• What is the difference between strategic experimentation and business model experimentation?

• Once through strategic experimentation and business model experimentation a dominant logic is achieved, the questions that most need to be addressed by entrepreneurs are: to what extent is the chosen organizational gestalt continuing to deliver returns and positive performance, and if less than optimal, what change would better effect attainment of projected targets?

• If decision makers eventual y do recognize that the existing organizational gestalt is less than optimal, and decide to stop committing further organizational resources, the question then becomes at what point too little is not too late.

• What are the effects of dyadic tension on new ventures?

• Which role does agility play in effecting the desired change?