1 An introduction to business models

(Written by Christian Nielsen, Associate professor, PhD, and Morten Lund, MSc., PhD-fellow)

[Please quote this chapter as: Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (2012), An introduction to business models, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon.com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

A business model is a sustainable way of doing business. Here sustainability stresses the ambition to survive over time and create a successful, perhaps even profitable, entity in the long run. The reason for this apparent ambiguity around the concept of profitability is, of course, that business models apply to many different settings than the profit-oriented company. The application of business models is much broader and is a meaningful concept both in relation to public-sector administration, NGO’s, schools and universities and us, as individuals. A recent contribution in this latter realm is the book Business Model You by Clark et al. (2012), which translates the ideas of Osterwalder & Pigneur’s (2010) business model canvas into a personal setting for career enhancement purposes.

Whether, in the case of the privately owned company, profits are retained by the shareholders or distributed in some degree to a broader mass of stakeholders is not the focus here. Rather, it is the point of this book to il ustrate how one may go about conceptualizing, analyzing or communicating the business model of a company, organisation, or person!

Sustainability is here interpreted as the propensity to survive and thus also the ability to stay competitive. As such, a business model cannot be a static way of doing business. It must be developed, nursed and optimized continuously in order for the company to meet changing competitive demands. Precisely how the company differentiates itself is the competitive strategy, whilst it is the business model that defines on which basis this is to be achieved; i.e. how it combines its know-how and resources to deliver the value proposition (which will secure profits and thus make the company sustainable).

In the last decades, the speed of change in the business landscape has continuously accelerated. In the late 1990’s, the e-business revolution changed global competition, and during the early years of the new millennium the knowledge-based society along with rising globalization and the developments in the BRIC economies ensured that momentum continued upwards. As new forms of value configurations emerge, so do new business models. Therefore, new analysis models that identify corporate resources such as knowledge and core processes are needed in order to il ustrate the effects of decisions on value creation. Accordingly, managers as well as analysts must recognize that business models are made up of portfolios of different resources and assets and, not merely traditional physical and financial assets, and every company needs to create their own specific business model that links its unique combination of assets and activities to value creation.

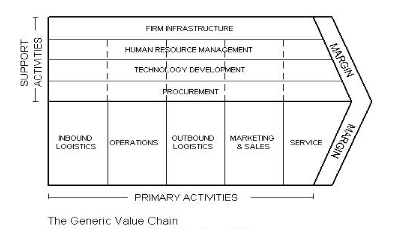

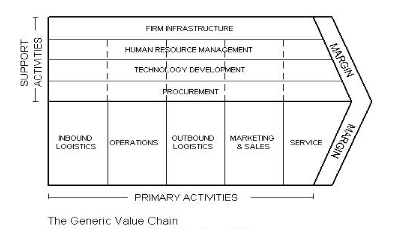

The rising interest in understanding and evaluating business models can to some extent be traced to the fact that new value configurations outcompete existing ways of doing business. There exist cases where some businesses are more profitable than others in the same industry, even though they apply the same strategy. This il ustrates that a business model is different from a competitive strategy and a value chain. A value chain is a set of serial y performed activities for a firm in a specific industry.

Figure 1: Porters Generic Value Chain, Porter 1988

The difference thus lies in the way activities are performed (strategic and tactical choices), and therefore a business model is closely connected to a management control agenda. The business model perspective has also been found useful for aligning financial and non-financial performance measures with strategy and goals. In addition, communicative aspects from executive management to the rest of the organization, and also to external stakeholders such as bankers, investors, and analysts, are also facilitated by a business model perspective.

1.1 Overview of the book

The field of business models is becoming a core management discipline alongside accounting, finance, organization etc. and we soon expect to see teaching modules on business models entering leading Masters and MBA programmes. This development is taking place as we speak, and at Aalborg University, this curriculum is already a mandatory part of several Masters level courses. This movement is in the coming years expected to be driven forth, partly by a call for greater interdisciplinarity within the core management disciplines and across the natural sciences, and partly because business model optimization and commercialization will become a political y driven issue in the light of innovation and sustainability pressures. At CREBS we believe that the focus on Business Models in policy-making and the business environment should be equal y as important as the present focus on innovation and technology development and will become a focal point of support for entrepreneurs and small and medium sized companies.

The “Vision” of this book is to be the most accessed and read book on business models by students, teachers and practitioners, and in due course to strengthen the relationship between innovation and commercialization activities and to make an impact on growth and sustainability of businesses.

The “Mission” of this book is to constitute an international y renowned platform that accompanies leading experts world wide and to affect business-related policy-making on regional, national and transnational levels.

This book is structured so that the first 4 chapters give a basic introduction to the field of business models. Then we il ustrate how the three main tendencies in business – networking, innovation and globalizing – are achieved through a business model perspective. Final y, we explore the inks between business models and profitability to greater extent.

1.2 Networking, innovating and globalizing

Organizational survival has been stressed several times in the introduction to this book. Why? Because it is adamant. Of course, some companies and organizations are situated in sweet spots, with lacking competition, lots of funding and market growth in terms of customers to serve. This is, incidental y, regardless of whether the organization is in the public sector or the private sector. However, the situation is more often than not one of competition, constant change in markets and demand and fights for resources, competences and capital. Especial y in the western world this is inherent.

Whoever thought that the financial crisis, which started back in 2007, was over has during the second half of 2011 been proven wrong. National banks, governments and corporations world-wide have continuously smaller room for maneuver and weaker tools for creating financial stability and growth as the crisis moves into new phases. As such, more citizens will in 2012 be questioning not just the future of the financial sector of the western world, but also the sustainability of the industrialized western society as a whole. On the one hand, pressure from under-burdened western society taxpayers (voters) who crave an average working week of 35-37 hours and retirement 40-50 years prior to their death will be on the rise.

On the other hand, eager hardworking Asian and Indian consumers with surprisingly well-educated workforces will lead us to be questioning our chances of economic survival in a truly globalized world all throughout 2012. One possible answer to this problem is that we to a greater extent need to rely on human capital in the quest for private sector value creation and competitiveness. However, human capital will not make the difference alone. Only when complemented by triple-helix based innovation structures, creativity and unique business models that commercialize innovation and human capital will this be an avenue to future sustainability of these societies.

So you see: business models are not only important; they are crucial! Henry Chesbrough, Professor at University of California, Berkeley, has at several occasions stated that he would rather have part in a mediocre invention with a great business model, than a great invention with a mediocre business model. It is in this light that the keywords networking, innovation and globalizing are brought forth. These are the key success factors for sustaining business growth moving forward and hence also society as we know it.

The title of this book specifical y emphasizes the three aspects networking, innovating and globalizing. We view these aspects as key success factors for sustaining business growth and thus they become cornerstones of the successful business models of the future. Networking and the ability to col aborate with key strategic partners in win-win based relationships will become even more vital for companies in the next years and decades. Building and encompassing e.g. win-win based relationships with strategic partners will require dedicated business model innovation and these aspects will be under severe pressure from the rising degree of globalization we are seeing in these years.

In the end the three success factors for sustaining business growth together have the potential to produce a whole new array of business model archetypes. The world has already seen the birth of the so-called Born Globals (REF here) and we expect to see other archetypes like Growth-symbioses and Micro– multinationals 1 emerge in the near future.

1.3 Value configuration

New value configurations such as those born out of the three success factors for future growth highlighted above reflect changes in the competitive landscape towards more variety in value creation models within industries. Previously the name of the industry may have served as a recipe for addressing customers. It doesn’t any more. Already in 2000, leading management thinker, Gary Hamel, quoted that competition now increasingly stands between competing business concepts. If firms within the same industry operate on the basis of different business models, different competences and knowledge resources are key parts of the value creation, and thus comparison of the specific firms even within peer groups now requires interpretation based on an understanding of differences in business models.

If firms only disclose accounting numbers and key performance indicators without disclosing the business model that explains the interconnectedness of the indicators and why the bundle of activities performed is relevant for understanding the strategy for value creation of the firm, this interpretation must be done by someone else. Currently, there does not exist much research based insight into how this reading and interpretation may be conducted, and it is very likely that this understanding of the value creation of firms would be facilitated if companies disclosed such information as an integral part of their strategy disclosure. We attempt to address these issues in detail in chapter 9.

1 At Center for Research Excellence in Business modelS we are currently working on series of research projects that map out the attributes of the two new business model archetypes Growth-symbioses and Micro-multinationals.

1.3.1 (One possible) verbal definition of a business model

A business model describes the coherence in the strategic choices which facilitates the handling of the processes and relations which create value on both the operational, tactical and strategic levels in the organization. The business model is therefore the platform which connects resources, processes and the supply of a service which results in the fact that the company is profitable in the long term.

This definition emphasizes the need to focus on understanding the connections and the interrelations of the bsuienss and its operations so that the core of a business model description is the connections that create value. This can be thought of e.g. by contemplating the silos by which the management discussion in the annual report normal y is structured. By themselves, endless descriptions of customer relations, employee competences, knowledge sharing, innovation activities and corporate risks do not tell the story of the business model. However, if we start asking how these different elements interrelate, which changes among them that are important to keep an eye on and what is the status on operations, strategy and the activities initiated in order to conquer a unique value proposition are effectuated, we will start to get a feeling for how the chosen business model is performing.

1.3.2 Conceptualizing the business model

Conceptualizing the business model is therefore concerned with identifying this platform, while analyzing it is concerned with gaining an understanding of precisely which levers of control are apt to deliver the value proposition of the company. Final y, communicating the business model is concerned with identifying the most important performance measures, both absolute and relative measures, and relating them to the overall value creation story.

A business model is neither just a value chain, nor is it a corporate strategy. There exist many value configurations that are different to that of a value chain, like e.g. value networks and hubs. Rather, a business model is concerned with the unique combination of attributes that deliver a certain value proposition. Therefore, a business model is the platform which enables the strategic choices to become profitable.

In some instances it can be difficult to distinguish between businesses that succeed because they are the best at executing a generic strategy and businesses that succeed because they have unique business models. This is an important distinction to make, and while some cases are clear-cut, others remain fuzzier.

One of the best examples of a business model that has changed an existing industry is Ryanair, which has essential y restructured the business model of the airline industry. As the air transport markets have matured, incumbent companies that have developed sophisticated and complex business models now face tremendous pressure to find less costly approaches that meet broad customer needs with minimal complexity in products and processes. While the generic strategy of Ryanair can be denoted as a low– price strategy, this does not render much insight into the business model of the company.

The low-cost option is per se open to all existing airlines, and many already compete alongside Ryanair on price. However, Ryanair was among the first airline companies to mold its business platform to create a sustainable low-price business. Many unique business models are easy to communicate because they have a unique quality about them; i.e. either a unique concept or value proposition. This is also the case for Ryanair. It is the “no-service business model”. In fact, the business model is so well thought through that even the arrogance and attitude of the top management matches the rest of the business. But they can make money in an industry that has been under pressure for almost a decade, and for this they deserve recognition. Ryanair’s business model narrative is the story of a novel flying experience – irrespective of the attitude of the customer after the ordeal.

A much applied example in the management literature is Toyota. However, Toyota did not real y change the value proposition of the car industry. They were able to achieve superior quality through JIT and Lean management technologies, and they may have made slightly smaller cars than the American car producers, but their value proposition and operating platform were otherwise unchanged. The same can be said for Ford in the early 20th century. Ford’s business setup was not real y a new business model. It sold one car model in one color, but so did most other car manufacturers at the time. Ford was able to reduce costs through a unique organization of the production setup, but the value proposition was not unique.

In the 1990’s, Dell changed the personal computer industry by applying the Internet as a novel distribution channel. This platform as a foundation of the pricing strategy took out several parts of the sales channel, leaving a larger cut to Dell and cheaper personal computers to the customers. Nowadays this distribution strategy is not a unique business model anymore as many other laptop producers apply it. Therefore, it is also a good example of the fact that what is unique today is not necessarily unique tomorrow.

This mirrors Christensen’s quote that “today’s competitive advantage becomes tomorrow’s albatross” (Christensen 2001, 105). Having the right business model at the present does not necessarily guarantee success for years on end as new technology or changes in the business environment and customer base can influence profitability. The point to be made here is that if the value proposition is not affected in some manner, then it is most likely not a new business model. However, it could be the case that the value proposition is not affected, but the business’ value generating attributes are radical y different from those of the competitors. Three examples of this are:

1. The value proposition of two companies producing kitchen appliances. One may be more high– end than the other, but this is a part of the competitive strategy, not the actual business model

2. The value proposition of two companies producing laptops. One may be priced lower because the range is smaller and the design kept to one color etc. This is not equivalent to different business models, but also a question of competitive strategy and customer selection. However, if one of the producers decides to alter the traditional distribution model, cutting out store placement and setting up technical support as local franchisees only, that could be a new business model

3. Two hair salons will both be performing haircuts, but their value propositions may be vastly different according to the physical setup around the core attribute

1.3.3 Which parameters do we need to understand?

Remembering that the business model is the platform which enables the strategic choices to become profitable, then it is clear that a business model is neither a pricing strategy, a new distribution channel, an information technology, nor is it a quality control scheme in the production setup. By themselves that is. A business model is concerned with the value proposition of the company, but it is not the value proposition alone as it in itself is supported by a number of parameters and characteristics, e.g. some of the parameters mentioned above like applied distribution channels, customer relationships, pricing models and sourcing from strategic partnerships. The key question here is therefore: how is the strategy and value proposition of the company leveraged?

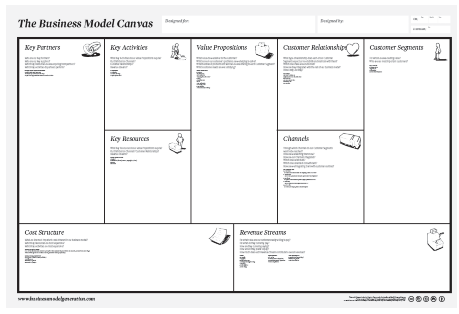

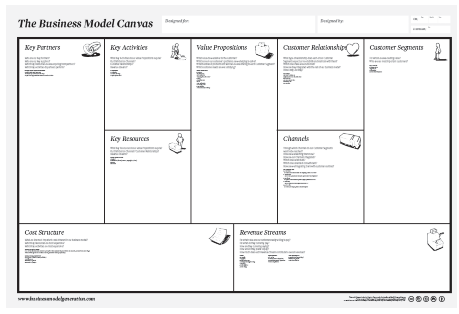

The problem with trying to visualize the “business model” of the company is that it can very quickly become a generic and static organization diagram il ustrating the process of transforming inputs to outputs in a chain-like fashion. The reader is thus more often than not left wondering how the organization actual y functions. Hence, the core of the business model description should be the connections between the different elements that the management review is traditional y divided into, i.e. the actual activities being performed in the company. Companies often report a lot of information about activities such as customer relations, distribution channels, employee competencies, knowledge sharing, innovation and risks; but this information may seem unimportant if the company fails to show how the various elements of the value creation col aborate, and which changes we should keep an eye on. One such idea on how to visualize the business model is the popular Business Model Canvas by Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010).

Figure 2: Business Model Canvas (www.businessmodelgeneration.com)

When we perceive relationships and linkages, they often reflect some kind of tangible transactions, i.e. the flow of products, services or money. When perceiving and analyzing the value transactions going on inside an organization, or between an organization and its partners, there is a marked tendency to neglect or forget the often parallel intangible transactions and interrelations that are also involved.

At the Center for Research Excellence in Business modelS (CREBS) we have recently analyzed how existing “models” or “tools” perceive transactions and relationships, and we have found that they general y lack a conception of intangible transactions, which in many cases are the very key to understanding the value logic of a business model. These ideas are discussed in depth in chapter 6 on value creation maps.

While value creation from an accounting perspective merely constitutes the realization of value at the time of sale of the product, i.e. registration of turnover, from a process perspective, value creation may be characterized as the steps leading towards value realization. Thereby we are in this genre more concerned with value creation potential, value creation processes and value creation extraction, which all can be said to precede the value realization phase.

In 2002 Chesbrough & Rosenbloom tried to corner the important aspects to be considered in order to comprehensively describe the business model of the company. They defined the business model as “[a] construct that integrates these earlier perspectives into a coherent framework that takes technological characteristics and potentials as inputs, and converts them through customers and markets into economic outputs. The business model is thus conceived as a focusing device that mediates between technology development and economic value creation. We argue that firms need to understand the cognitive role of the business model, in order to commercialize technology in ways that will allow firms to capture value from their technology investments” (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom 2002, 5). This definition is worth noticing because it was among the first one to set value creation as a central notion of understanding the points of concern in the business model of a company.

In the wake of this definition, they define six elements which make up the business model:

1. Articulate the value proposition, that is, the value created for users by the offering based on the technology

2. Identify a market segment, that is, the users to whom the technology is useful and for what purpose

3. Define the structure of the value chain within the firm required to create and distribute the offering

4. Estimate the cost structure and profit potential of producing the offering, given the value proposition and value chain structure chosen

5. Describe the position of the firm within the value network linking suppliers and customers, including identification of potential complementors and competitors

6. Formulate the competitive strategy by which the innovating firm will gain and hold advantage over rivals

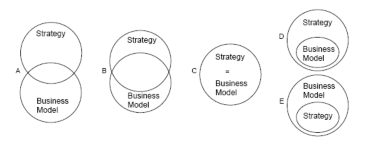

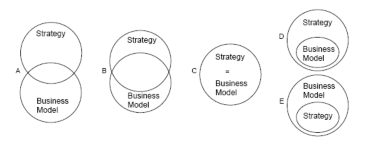

It is interesting to note that Chesbrough & Rosenbloom in the above take in strategy as an element of the business model. The relationship between business models and strategy is, if not fuzzy, then at least undecided. In her book from 2002, Joan Magretta defines business models as “stories that explain how enterprises work”, and notes that strategy, understood as how to outmaneuver your competitors, is something different from a business model. Seddon et al. 2004 take part in this discussion by schematizing the possibilities in figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Possible concept overlaps between business models and strategy (Seddon et al. 2004)

If we briefly recap the business model definition given above: “A business model describes the coherence in the strategic choices which facilitates the handling of the processes and relations which create value on both the operational, tactical and strategic levels in the organization. The business model is therefore the platform which connects resources, processes and the supply of a service which results in the fact that the company is profitable in the long term”, it is evident that it takes the stance of Seddon et al. s (2004) option E, because it sees the business model as the platform that enables strategy-execution.

1.4 Driving out the business model

In order to start working with clarifying the business model of a company or an organization, one can start off by asking the following questions (regardless of which business model framework one chooses for structuring and visualizing the business model during the process):

• Which value creation proposition are we trying to sell to our customers and the users of our products?

• Which connections are we trying to optimize through the value creation of the company?

• In which way is the product/service of the company unique in comparison to those of major competitors?

• Are there any critical connections between the different phases of value creation undertaken?

• Can we describe the activities that we set in motion in order to become better at what we do?

• …and can we enlighten these through relevant performance measures?

• Which resources, systems and competences must we attain in order to be able to mobilize our strategy?

• What do we do in relation to ensuring access to and developing the necessary competences?

• Can we measure the effects of our striving to become better, more innovative or more efficient, apart from the bottom line?

• Which risks can undermine the success of the chosen Business Model?

• What can we do to control and minimize these?

1.5 Archetypes of business models: looking for patterns

Other authors have attempted to define business models by discussing and identifying overall business model generics and archetypes. Business model archetypes was, as will be described in greater detail in chapter 2 on the history of the business model concept, one of the primary discussions in the field in relation to e-business models.

Already in 1998, Timmers classified 10 generic types of Internet business models:

• e-shop

• e-procurement

• e-auction

• 3rd party marketplace

• e-mal

• Virtual communities

• Value chain integrator

• Information brokers

• Value chain service provider

• Col aboration platforms

Two years later, Rappa (2000) identified 41 types of Internet business models and classified them into 9 categories, which were fairly similar to Weill & Vitale’s eight (e-)business models from 2001:

• Content Provider

• Direct to Consumer

• Full Service Provider

• Intermediary

• Shared Infrastructure

• Value net integrator

• Virtual Community

• Whole of Enterprise/Government

In recent years it is to a rising degree being realized that archetypes of e-business in reality merely are translations of already existing business models. And thus business model archetypes seen through today’s lenses could be something along the lines of:

• Buyer-seller models

• Advanced buyer-seller models

• Network-based business models

• Multisided business models

• Business models based on ecology

• Bottom of the pyramid business models

• Business Models based on social communities

• Co-creation and consumer-col aboration models

• Freemium models

Osterwalder et al. 2010 and Johnson 2010 provide more inputs on business model archetypes or patterns as they may also be called.

Sum-up questions for chapter 1

• What is the difference between strategy and business models?

• What is the difference between a business model and a value chain?

• What is a business model archetype?

• Find real life examples of the various business model archetypes