2 A brief history of the business model concept

(Written by Christian Nielsen, Associate professor, PhD)

[Please quote this chapter as: Nielsen, C. (2012), A Brief History of the Business Model Concept, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon.com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

Business models have been intimately connected with e-business since the rise of the Internet during the late 1990’s. Kodama (1999) and Hedman & Kalling 2003 provide early reviews of the business model concept as seen around the dot.com era and the rise of the e-business model, while a more recent account of events and developments can be found in Fielt’s 2011 review.

Around 2001-2002, the concept of the business model started receiving a much more general meaning in management literature than the e-biz rhetoric which had surrounded it in the first years. Despite the definition of a business model still being “fuzzy at best”, in the words of Porter (2001), his colleague Joan Magretta, for instance, gained much attention by perceiving business models as “stories that explain how enterprises work” (Magretta 2002, 4). According to Magretta, business models did not only show how the firm made money but also answered fundamental questions such as: “who is the customer? and “what does the customer value?” (Magretta 2002, 4). Precisely this aspect of value seen from the point of the customer made a big impact on the existing thinking.

Further, a basic idea of the business model concept was that it should spell out the unique value proposition of the firm and how such a value proposition ought to be implemented. For customers such “value creation” could be related to solving a problem, improving performance, or reducing risk and costs, which might require specific value configurations including relationships to suppliers, access to technologies, insight in the users’ needs etc.

In the late 1990’s the ‘business model’ concept became almost synonymous with e-business and the emergence of the so-called new economy. The Internet had in essence created an array of new business models where the major focal point of the literature on business models from an e-business perspective became how to migrate successful y to profitable e-business models. Therefore, much of the business model literature focusing on the e-business context concerned how such organizations could create value in comparison to their bricks and mortar counterparts. The only problem with the early e-business models was that they tended to forget the actual profit-formula or at best be completely overoptimistic on the conversion of Internet traffic to actual profits.

As such, far from all ways of doing business through the Internet were profitable, and accordingly there has been a substantial interest in explaining how the nature of the new distribution and communication channels formed parts of new business structures. One way of approaching this issue was through Amit & Zott’s (2001) four dimensions of value-creation potential in e-businesses that has to be in place for an e-business model to be profitable: It must create efficiencies in comparison to existing ways of doing business, and it must facilitate complementarities, novelty or enable the lock-in of customers. For example, the creation of efficiencies can be seen as the underlying notion of Internet-based business models in the banking industry, while e-commerce as a new distribution channel has created efficiencies thus enabling new business models to emerge.

In the late 1990’s the mere naming of companies as ‘dot-com’ was enough to signal that the business model of the company was potential y profitable or at least attractive for investors. However, after the tech stock crash, analyst and investor behaviour changed so radical y that signaling dot.com had the opposite effect. In a blow, it was no longer viable just to imitate an Internet-company business model. Now profit generation is required regardless of ones distribution channel. This led to several authors stating that the profit-formula should still be a central feature of the business model. Based on dominant revenue models on the Internet, Afuah and Tucci (2003) identified four profit-formulas for e-businesses:

• Commission

• Advertising

• Mark-up

• Production

It is worth noting that “[m]uch of what is being said about the New Economy is not that new at al . Waves of discontinuous change have occurred before”, as Senge & Carstedt (2001, 24) state. Just think of how Henry Ford’s business model revolutionized the car industry almost a century ago, or how Sam Walton revolutionized the retail industry in the 1960’s with his information technology focus and choice of demographic attributes for store locations, thus creating an immense cost structure focus along with a monopolistic market situation. These notions are what Hal Varian denotes as discontinuous innovation.

Although the present focus on business models within academic and practitioner circles to a great extent can be related to their earlier discussions within an e-business context, the importance of the business model perspective is far from only relevant in certain distribution channel structures. The transformation of the inter- and intra-company value chain is ongoing in almost all areas of the economy and this considerably challenges the markets and its enterprises. “Much talk [of business models: Ed.] revolves around how traditional business models are being changed and the future of e-based business models” (Alt & Zimmermann 2001, 1) but this is merely half the story. Business models are perhaps the most discussed and least understood of the newer business concepts.

Taking one’s point of departure in a business model perspective can have multiple purposes. Among the advantages of this approach is the possibility of enabling company management to structure their thoughts and understanding about strategic objectives and other relevant issues. Furthermore, this facilitates the conveyance of ideas and expectations the management has to the employees on the business process level and to the technical y oriented functions. There are clear linkages to creating an understanding of the overall functioning of the firm in and, in addition, a focus on communicating the management perceptions of the business internal y in the firm. Accentuating these thoughts on creating a common understanding of the business, its strategy and objectives within the entire enterprise, Hoerl (1999) further argues that the application of the business model helps to structure the addressing of key business issues and that an effective business model ought to incorporate aspects such as culture, values, and governance.

Conceptualizing the Business Model is therefore concerned with understanding the ‘whole’ of the business and its value creation logic. There exist a number of different value configuration types other than the value chain, and newer types of value configurations to a large extent reflect changes in the competitive landscape. There is a tendency that today a greater variety exists in value creation models within industries where previously the “name of the industry served as shortcut for the prevailing business model’s approach to market structure” (Sandberg 2002, 3). Competition now increasingly stands between competing business concepts, as Gary Hamel (2000) argues in his book ‘Leading the Revolution’, and not only between constel ations of firms linked together in linear value chains, as was the underlying notion in the original strategy framework by Porter (1985).

If firms within the same industry operate on the basis of different business models, different competences and knowledge resources are key parts of the value creation, and mere benchmarking of key performance indicators will not be able to provide any meaningful insight into the profit or growth potential of the firm. Comparisons of the specific firm with its peer group will more often than not require interpretation within an understanding of differences in business models.

It is by no means a new idea to create a model of the organization, which a business model, understood as a model of the business, may be perceived as. Organization charts and diagrams showing how departments and divisions interact with and affect each other are well known. However, a business model comprehends something more than just the diagram. It should at least include a coherent understanding of the strategy, structure and the ability to utilize technological solutions to create value, which are three very significant attributes. A prominent, almost state-of-the-art example il ustrating precisely these three components, is Del . Del ’s strategy is direct sales, and the company is structured around the utilization of information technology, almost like a hub, in this way enabling online ordering, custom built pc’s and direct shipping (Kraemer et al. 1999), i.e. an extension of the existing personal-computer business model via a unique strategy, structure and the application of information technology (Magretta 1998).

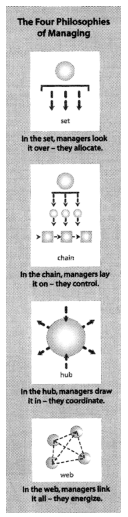

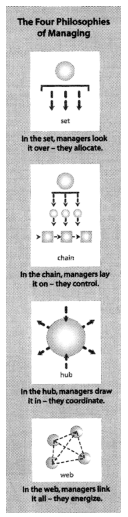

Unlike traditional organizational diagrams and charts that merely il ustrate the actions of an organization and the formal organization, organigraphs enable the drawing of organizational action by demonstrating “how a place works, depicting critical interactions among people, products, and information” (Mintzberg & Van der Heyden 1999, 88). Organigraphs consist of four basic components: the set, the chain, the hub, and the web that are applied in visualizations of the organization in order to il ustrate its concrete relationships and processes. The first two components are rather conventional and are also found in the more traditional organizational il ustrations, while the two latter components are novel introductions.

Figure 4: Organigraphs (Mintzberg & Van der Heyden 1999)

The set refers to a collection of separate parts, a portfolio so to speak. For instance, this could be a set of independent activities, e.g. performed in two independent divisions or by two individual lawyers in the same company. As opposed to the set, the three remaining components are all characterized by some sort of connectivity. The first one, the chain, describes a sequential connectivity of activities, e.g. like in Ford’s automobile factory. Applying chains as connections promotes standardization and enhances reliability. The third component, the hub, serves as a coordination center. This could be both in a physical form (e.g. a manager) and in the form of a conceptual point of reference (e.g. an intranet). Basical y, “[h] ubs depict movement to and from one focal point. But often connections are more complicated than that” (Mintzberg & Van der Heyden 1999, 89). This is where the final component, the web, comes in. Examples of such a type of organizational connection are teams or the notion of interactive networks. This way of il ustrating how organizations work has been applied by Thrane et al. (2002) to identify relevant performance measures, since managerial action must be determined by the dilemmas of control management faces.

According to Chesbrough & Rosenbloom (2002, 530), the origins of the business model concept can be traced back to Chandler’s seminal book ‘Strategy and Structure’ from 1962. Strategy, Chandler states, “can be defined as the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals” (Chandler 1962, 13). Further developments in the concept travel through Ansoff’s (1965) thoughts on corporate strategy to Andrews’ (1980) definitions of corporate and business strategy, which, according to Chesbrough & Rosenbloom (2002) can be seen as a predecessor of and equivocated to that of a business model definition.

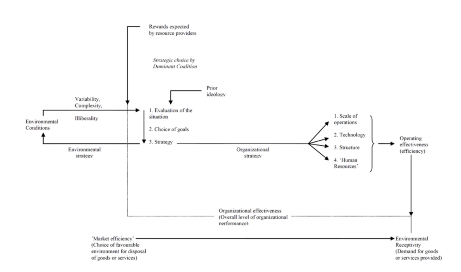

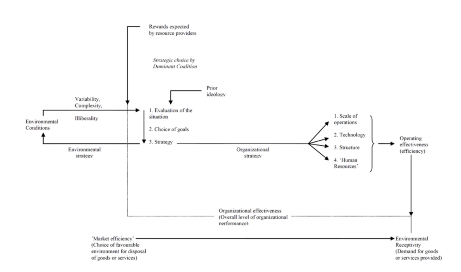

Child’s (1972) paper on organizational structure, environment and performance, incidental y to a great extent influenced by Chandler’s work, is, however, among the earliest to gather and present these thoughts diagrammatical y. Although he does not explicitly refer to his schematization of “the role of strategic choice in a theory of organization” (Child 1972, 18) as a business model representation, the thoughts presented here incorporate many of the central elements presented within the recent literature on this emerging concept. For instance, Child’s term ‘prior ideology’ covers the aspects of vision and value proposition, objectives, and strategy of an organization, while ‘operating effectiveness’ is viewed as an outcome of the organizational strategy and the elements: scale of operations, technology, structure, and human resources.

Figure 5: The Role of Strategic Choice in a Theory of Organization (Child 1972)

The role of technology in relation to the business model is not to be underestimated, as it is a key element in determining which organizational structures become feasible, because it influences the design of the business, i.e. its underlying architecture. Thompson’s ‘Organizations in Action’ (1967) can in this respect be regarded as laying the foundation for studying the impact of technology on the feasibility of business model concepts. Thompson (1967) proposed a typology of different kinds of organizational technologies, distinguishing between long-linked, intensive and mediating technologies. These different technology types play different roles in connection with value creation and thus also the business model.

The management of fundamental strategic value configuration logics such as relationships to suppliers, access to technologies, insight into the users’ needs etc., can be just as important and relevant as inventing new revolutionary business models.

Besides this brief review of the background of the business model movement, it is important to note that there exist multitudes of different angles within which the business model concept could be addressed. In Hedman & Kalling‘s (2003) review, the focus is on business models from an e-business and information technology perspective, while Osterwalder’s 2003 review enhances the understanding of the business in order to improve information system design through a ‘business model ontology’. However, an information system perspective merely reflects a minor segment of the business model movement as will be evident in particularly chapters 3 and 5 below, but also the chapter concerning business model innovation (chapter 6) and globalization of high-technology ventures (chapter 7).

The innovation perspective on business models, which encompasses both business development and new business ventures, is at the present one of the fields where the business model movement experiences the greatest momentum. However, this field of auditing was among the first fields to embrace the ideas of understanding business models and value creation. Also within the fields of voluntary reporting and disclosure and communication has the concept of business models been discussed and applied vividly.

Sum-up questions for chapter 2

• Why was the e-business revolution so important to the rise in focus on business models?

• Discuss the relation between strategy and structure from a business model perspective

• What is the difference between an organigraph and a business model?